Post-Human Post-Cinema

Post-Human Post-Cinema

HBO's Westworld

Unpublished, Melbourne, 2019Part 2 - Unreading the Opening

When the first episode of Westworld commences, it appears to be happening somewhere at some point in time. Pragmatically, it unfolds within the Delos Corporation, the company responsible for designing, engineering, maintaining and marketing the immersive entertainment venture known as Westworld. Temporally, it unfolds somewhere just beyond our present, in that nebulous phantasmal zone of the 'not too distant future' – a time-frame over-occupied by the bulk of cinematic and televisual dystopian sci-fi. But considered with lateral depth, Westworld's time and place is multiple, flexible, reversible and controvertible. Here we seek to track Westworld's spatio-temporality to measure its proximity and remoteness to a range of design worlds, story realms, semiotic stages and industrial terrains.

Within Westworld's fictional schema (pieced together across the first handful of episodes), the Delos Corporation oversees six theme parks of which Westworld is one. The front-end of each park is where the android hosts interact with the human guests; the back-end is governed by a rigorous management system whose department heads run the key tasks undertaken by five core departments: Narrative, Behaviour, Quality Assurance, Livestock Management and Manufacturing. The imaginary design of this corporation and its managerial logistics and infrastructure at once articulates Westworld's sci-fi speculation of the potential corporatization of AI, and services the labyrinthine narrative which is revealed and traversed across the series by its hosts, guests, directors and audience. If literature is a 'top-down' godlike authorial feat, Westworld's hyper-allusionist multi-referential generic assemblage is 'bottom-up': it deploys its characters in motivational arcs designed to query and reveal the means and purpose of their authored existence. This is the 'warning light' that signals Westworld as post-human post-cinema. Its 'story' is the machine of itself, voiding you and I in both its writing and reading.

Accepting Westworld less as an imaginary tale and more as an archaeo-corporate empire of narrative, let us consider its multiplicity as a "model of matrixed nodes of human identity, human form, human biology and human neurology" mentioned earlier in Part 1. To enact this analytic procedure, I hold in mind the model of Lidar (light imaging, detection and ranging) in order to perceive the simultaneity of Westworld's layers. Lidar, put simply, utilizes a laser beam to gauge the proximity and position of an object in a defined space, hence Lidar's use in assembling data to construct a visualization of a zone which does not offer its topography to optics alone (e.g. dense forests, underground caves, underwater formations, etc.). In terms of 'visualizing Westworld's topography', one could choose a particular mode of analysis for discoursing on the series, and adjust one's frequency reception in order to scan the series and generate an analytic image which would reveal a discursive layer. In the spirit of this experiment, four core 'frequency domains' are articulated in this textual analysis of Westworld (in no sequential or hierarchical order):

• the intertextual/cybernetic domain (sited in Japan and replicating key post-human anime – Ghost In The Shell and Akira - covered in Part 1)

• the fictional/mythological domain (sited in the USA and recalling a range of 'mutant Westerns' and Italo-Westerns – notably Once Upon A Time In The West)

• the metatextual/plastic domain (sited in Disneyland and resembling HBO's hall of mirrors and its treatment of movie morphology as an inhabitable terrain for postmodern consumption)

• the textual/linguistic domain (sited in France and replaying operations of Nouveau Roman cinema – particularly The Man Who Lies)

To sum this up blithely: Westworld poses like Japanese anime, calls itself a western, is modelled after Disneyland, and behaves like French intellectual cinema. Yet this alone does not define an operation of either post-humanism or post-cinema; most clever-clever time-based audio-visual productions have operated this way for decades now in cinema, television, advertising, music videos and video art. Westworld's difference - even be it a momentary and slight one - is the holistic way in which if forms its world in the image of 'world-making' which now prosaically governs whatever you designate to be a 'world'. For example, this difference can be noted in the shift from (a) smarmy politico journalists in the 1980s linking Ronald Regan’s Strategic Defense Initiative to Star Wars, to (b) our millennial currency wherein Oculus VR founder Palmer Luckey’s Virtual Mexican Wall transfers his dreams of futurological technologies into a start-up that actualises the US government's Secure Border Initiative. Luckey's 'disruptive innovation' employs lo-end componentry to detect border intruders through sensors, lasers, opto-thermal recognition, AI aggregative learning and mobile network task response. It's cheap, immediate, decentred, and – crucially ¬– founded on gamer mechanics and shooter iconography.

This is not simply 'science fiction as science fact': it is a climate wherein 'agents of change' are implementing actions based on their cherished mytho-cine gamer-tech fantasies. These innovators are bent on translating their dreams into their own corporatized 'dreamworks'. As cinema insists on being a dream factory of sorts, it persists in denying that it is an outmoded engine of theatrical posture, especially when it peddles humanist, essentialist and universalist Uzi-sprayed fables. By comparison, HBO cine-effects are actualised through the ‘disruptive innovation' of exploding and rupturing the authorial, semantic and symbolic operations presumed to be part of cinema's grand empire. Eschewing classical literary analytic models as well as their screenic applications, our Lidar metaphor of analysis is warranted by Westworld's millennial logic where 'real-world', 'in-world' and 'out-world' are interfaced and merged.

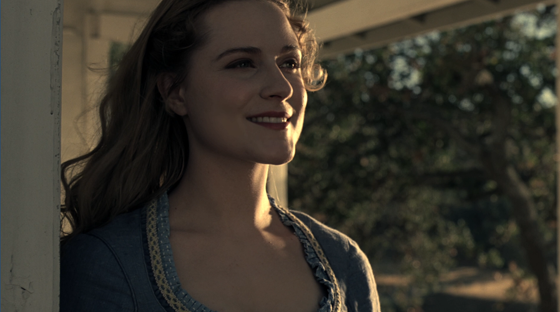

And so, let us return to the opening of the first episode of Westworld and execute multiple scans of its first 13 minutes. Within this small time frame, much of the whole series is encapsulated, as the incidents described will be repeated across numerous episodes, each time with modulated degrees of consciousness in the behavioural responses of the android hosts, the human guests, and the 'you and I' reading the narrative. The plot is a swift sequence of archetypal set-ups of the Western genre: girl wakes up on her father's farm; goes into town; boy travels to town; walks down its main street, enters a saloon for a drink and is solicited by a prostitute; boy spies girl in the distance; exits the bar and picks up a food tin she has just dropped; they ride across plains and observe cattle being herded; they arrive at the girl's family farm where her father and mother have just been murdered by a gang; the boy heroically guns them down, but fails to gun down a mysterious man-in-black who shoots the boy, then drags the girl screaming to the barn where he will likely perform unthinkable acts with her.

The twist is that this sequence of events is presented as a pre-programmed concatenation of pre-determining events. They are being recalled by the girl - Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) - who is an android host. Naked and immobile, she sits upright on a laboratory table in a dark clinical environment, spot lit under fluoro lights. A slow-zoom toward her lithe corpus accompanies her voice-over narration as she responds to prompts from an unseen programmer (Bernard, played by Jeffrey Wright) who interrogates her level of consciousness as a programmed entity. After a prompt to "bring her back online", Bernard speaks directly to Dolores. Responding to his interrogation, she speaks at a meta-textual level: 'out of character', 'off-script' and sans her dang-twang Western accent. Their exchange might be temporally unspecific (the dialogue laid atop the mute image of a motionless Dolores) or it might be temporally synched to the image (as if the exchange we are hearing is an auralization at the CLI [command line interface] level of Bernard performing diagnostics on Dolores' OS). From the opening sentence uttered in Westworld's first episode, the relationship between locutor and auditor is unfixed. In an advancing era of highly competitive NLUIs (natural-language user interfaces, most known through the machine-learnt prompted-responses of Apple's Siri and Amazon's Alexa), the once-human voice is becoming less an expression and more an assisted sonification under the guise of linguistic exchange. Westworld is a possible first in incorporating this shift from the spoken to the programmed – from the authored to the generative, from the expressive to the responsive - into its textual composition.

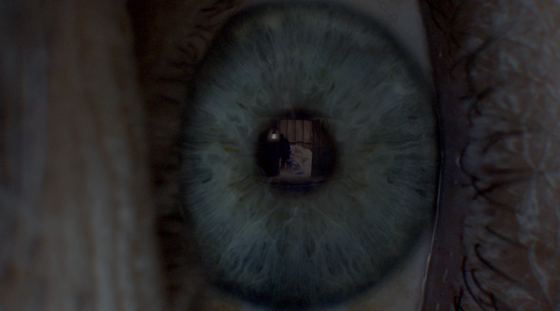

When Bernard asks her where she is, Dolores replies "I'm in a dream". She isn't. She is in a reality which limits her sense of self so as to perceive her consciousness as residing in a dream state. This is post-humanism personified: her unconsciousness – her subliminal functionality – lives in her waking/working state, while her true purpose and design lives in what she perceives to be a dream state (attainable only through her being taken offline). As such, Dolores is her own 'dreamwork' – a 'working dead' that embodies the conditions of earning a wage in our contemporary conditions of employment. Frozen in stasis-mode while Bernard carries out his diagnostics, Dolores' death state is proven as a fly crawls over her face and eye. She remains unresponsive; her lack of tactility is non-signifying. If she were human, she would be read as being unemotional. Such is the defining trait sought via the 'empathy test' conducted by Dekker (Harrison Ford) in the original Bladerunner (1982) as he feeds emotion-triggering scenarios to suspected androids while scrutinizing their retinal flux through an enlarging lens. But as an android, her unresponsiveness demonstrates her pliability, her commandability, and her general capacity to be written. Dolores' non-functioning corpus is her CLI, prised open offline by Bernard as he queries whether she is code alone.

When Bernard asks Dolores "Have you ever questioned the nature of your reality?" he instigates a textual moebius strip. Dolores' recitation of how she views her programmed life (including its prime directive to allow the guests to immerse themselves in their co-inhabited constructed world) activates the initial actions depicted in the first episode: the farm home, the train journey, the main street, the bar, the chance encounter, the steer plains, and the climactic shootings back at the farm. Viewed this way, we are less being told a story than we are having the programmed events demonstrated as a code run. The thrill for the guests of Westworld - especially the 'newcomers' - is how they can lose themselves in the programmed variables which arise from their interactions with scenarios, figures, elements, haptics and sensations. The complexity of the theme park's design is not in simply making realistic androids behave in a life-like manner: it lies in suppressing the androids' AI machine-learning exponentiality from achieving an android consciousness.

Teddy Flood (James Marsden) exemplifies the successful outcome of this coding. He is introduced travelling on a train across the Utah buttes (first 'ocularized' in the opening credit sequence). He innocently looks out the window like William Blake (Johnny Depp) in Dead Man (1992) – even though he is within ear-shot of a returning guest talking to a newcomer about 'going straight evil' as a thrilling mode of interaction with Westworld's realistic game-play. This amounts to, say, Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) in The Searchers (1956) hearing John Ford discuss with the cinematographer the set-up for the scene. (Degrees of similar self-reflexivity are to be found in 'mutant Westerns' like Zachariah and Red Sun [both 1971], Rustlers' Rhapsody [1985] and Django Unchained [2012].) Combined with this deep-rooted denial of technical consciousness, Teddy's gosh-darn honesty and his lack of gumption cast him as the cliched good-guy-gunslinger, a figure terrorized and parodied throughout the Western genre's history. Locked into character, he has been programmed to perceive the rolling plains before his eyes as semiotic signage. Like the drone fly-overs and the digital 'match move' tracking of the train within this panorama, the landscape looks simulated because the Westworld theme park is created from the backdrops of the mythological Western, not the mythical West. Dead Man's William Blake sees the historical West through our revisionist eyes; Westworld's Teddy sees the terraformed West through the Delos corporation's vision.

Synchronized to this scene, we hear Dolores in voice-over: "At one point or another, we were all new to this world". Dolores's AI-programming 'thinks' that she has come to the New World "to be free, to stake out our dreams - a place with unlimited possibilities". This is America. This is New York. This is Hollywood. This is Burbank. This is HBO. This is Westworld. She locates all these spaces simultaneously, because she is speaking off-line while holding to the overarching purpose of her creation. This amounts to, say, Ethan Edwards declaring in voice-over in The Searchers that his role is to perform as a neo-classical icon of Americana mythology for the genre from which he gains his main employment. Well might one acknowledge this as a cute spin on self-referentiality in the current entertainment industry, but Westworld admits its fictive manipulations in order to then cajole the audience - both the park's 'newcomers' and the series' 'new viewers' - into suppressing such admissions.

The entrance of Teddy into 'the Western' is a 'first run' beta test for the audience. One watches it like an unfolding story, but it unpacks itself in the same way his OS is compressed into textual silica. The androids run their scripts hermetically, equally incognisant of anything beyond their world and anyone (droid or dude) they encounter. Their AI is blocked, redirected and channelled, just as script-writers corral their characters into pathways and situations. This opening scene of Teddy is there only to be repeated endlessly, like a monkey at a typewriter not knowing who James Fenimore Cooper is. The irony is that when the monkey aleatorily types out The Last Of The Mohicans, then it would neither know what it did, nor be able to read it.

In keeping with this spread of suppression, films or movies are never mentioned in Westworld. When newcomer guests arrive, their comments express their surprise at how 'real' everything looks, rather than how much it 'looks like a movie'. (No one marvels at anything real these days; only things evoking scenes from films warrant exclamation.) Westworld structurally seals off the referentiality of real-world social exchange in order to control its own bordered zone of fiction – which is apt as the premise of the theme park is precisely modelled on such mechanics. Its guests are as interred as the androids are controlled. In keeping with the suppression of AI consciousness and the labyrinthine non-disclosure of its code from both employees and users, Westworld never names its sources. Yet one can read its synaptic cine-semaphoric references.

When Teddy disembarks the train and walks down the main street, we see the township is named Sweetwater. There are about fifteen Sweetwaters spread across fifteen states in the USA. The term is rooted in the late 19th century American mythology of building new towns within reach of fresh water, hence its referencing in numerous Western movies set in zones where the desert can become a garden for industry to prosper. But the salient reference would be to Sergio Leone's masterwork Once Upon A Time In The West (1969). The tracking shot following Teddy as he walk's down Westworld main street replays Jill (Claudia Cardinale) arriving at Flagstone: an outpost in the midst of being built. She rides in a horse and carriage through what effectively is a frontier town of the future, one awaiting for industry to take hold of the terrain. The secret to its development lies some distance out of town at the Sweetwater ranch which her now-deceased future husband had purchased cheaply, predicting that its undisclosed well water will prove vital in the eventual extension of the burgeoning railroad as it inches toward the Pacific Coast. Once Upon A Time In The West is simultaneously a savagely revisionist Western (full of lustful violence, ruthless maverick capitalism, and a majestically morbid sense of purpose) and a dormant futurist critique of maverick American capitalism (culturally focussing on diasporic Italian immigrant labour upon which the American empire had been dependent).

Like a virtual interactive museographic translation of Leone's vision of frontier boosterism, Westworld's main street is staged as the public facade of New Frontier social exchange, where enterprise drive precedes civic duty. The main street is a corridor of business; the town hall comes later; the sheriff’s is but one business among many. Iconically, this main street is like a museum of living tableau – part archaeological excavation, part Disneyland's own "Main Street U.S.A." (opened in 1955). Disneyland's welcoming thoroughfare serves as the conveyor belt access to the end hub where patrons choose to visit the other four lands: Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland and Tomorrowland. The strip is based on frontier town architectonics (singular two-way passage bordered by hoardings labelling the strip's commercial sites), enshrining enterprise as the building blocks for any ideal notion of a new world. Westworld's vignettes seen through the eyes of Teddy (a hammer striking an anvil, kids placing a scorpion on the bald pate of a sleeping old buzzard, a dame under a parasol enjoying a carriage ride, a grizzled sheriff soliciting volunteers for a posse, a flash of a daguerreotype portrait, etc.) appear like Disneyland animatronics. And that's exactly what they are, evidencing Westworld to be Disneyland for real. Consequently, Westworld is an anti-Deadwood, a hyper-revisionist Western inverted to be a simulation of first degree genre production. Just as The Searcher's Ethan Edwards denies the existence of John Wayne who embodies his existence, all the androids of Westworld live as if there is no such thing as either Westworld or Westworld.

This denial of textual operation and corporate manipulation reaches a psychological apotheosis when bar girl Clementine (Angela Sarafyan) caresses Teddy's face and says "You're new" as he leans back and swigs a shot of whiskey in the salon. He isn't new. Nor is she. Nor is their interaction. He is programmed to be an in-world newcomer host to Sweetwater who symbolically performs like an out-world newcomer guest. His non-newness operates at two levels: his lack of cybernetic consciousness, and his lack of frontier cynicism. Furthermore, as a soliciting prostitute, Clementine has no vested interest in the veracity of anything she says. Her dialogue is a random algorithmic fishing for triggers, uttering words purely to gauge a response from a potential client so as to snare a contract with him. In the exploitative end of the sex worker industry, pimps snare women for a stable through identical word play. Zooming out further, movie dialogue operates on its audience similarly, if not identically.

Clementine is a corporeal sine qua non of capitalist exchange. As a prostitute selling herself, she fuses product, produce and productivity by being both salesperson, sales pitch and sales item. Her glazed eyes (stunningly controlled in the carefully modulated performance by Angela Sarafyan) signal the nullification of self that is crucial to all forms of performativity. Her third sentence: "I'll give you a discount." Two androids seducing and being seduced, haggling and being haggled, each at the cusp of a business exchange of phantom values.

Similarly, Teddy's chance encounter with Delores has been scripted as if it has been predestined: the fateful meeting of soul mates. Westworld's hermeneutics (scripted by its Narrative department) constitute a corporatized imagineering of how life unfolds for the benefit of people, but only as a means to benefit from people. Interrogated by Bernard in the voice-over as to whether Dolores experiences any inconsistencies or repetitions in her world, Dolores responds that "any day, my whole world could change with just one chance encounter." She says it like she believes it because she has been programmed to do so. Bernard (the head programmer in Westworld's Behaviour department) is scrutinizing Delores (an android programmed to behave reactively to braided bifurcating narrative threads). As a progressivist alternative content provider, HBO delivers product to humans believing that their consumption of HBO's signature 'quality character-driven drama' affords them an escape from the routinal scripting of bland network televisual drama. As such, Bernard's question is textually directed to Westworld's audience, congratulating them on their locative listening – their ability to register the script's cleverness.

The 'cleverness' voiced by the programmer Bernard is then extended in a playful exchange between Teddy and Dolores themselves. All modern revisionist narratives of hetereo couples extol a knowingness through the characters' self-awareness of their own self-scripted exchanges in the playful theatrics of small battles of the sexes. Broadway and Hollywood have long parlayed memorable scenes from these playful yet signifying conflicts in all genres. After Teddy picks up the dropped tin and hands it back to Dolores, they each pretend to be meeting each other for the first time. It becomes apparent that this is a lovers' game: Teddy has returned to Sweetwater to meet up with Dolores again. Teddy spied Dolores 'by chance' through the saloon window while Clementine attempted to secure him for trade. Dolores 'by chance' drops a tin just as Teddy reaches down in time to pick it up for her. The blurring between engineered events and chance occurrences is at once highlighted and negated: these two androids behave as programmed because chance was never part of their Boolean existence.

Dolores mounts up and rides off, cajoling Teddy to keep up with her. When they reach a high plain vista, they observe a cattle herd she tends for her father's ranch. Teddy cannot read their movement; Dolores can. She points out the Judas Steer: "the rest will follow wherever you make him go." Dolores claims that she "just knows these things" when queried by the naive Teddy. This is another instance of default disavowal of recognition: her scripting blocks her AI consciousness, engineered by programming to make Delores believe she is a character. Symbolically, Dolores is the Judas cow, playfully steering Teddy, cynically steering Westworld's guests, unknowingly steering the Westworld corporation, and textually steering the viewers of Westworld.

'Steering' and 'cattle' are plausible nodes in a Western's scenography, but in Westworld they archly relate to Reactive Planning. In AI programming, 'steering' refers to a key enabling device whereby agents are herded in the direction of making and taking actions as if in direct reaction to apparent conditions. This Svengali-like coding strategy allows for a seemingly random sequence of events to unfold, but like the whole premise and construction of Westworld and the series' production, 'chance encounters' and 'emotive responses' are what we could call highly algorithmized.

Furthermore, 'cattle' sardonically refers both to humans watching the series (HBO's 'public viewing sphere') and what the Westworld corporation terms 'livestock': the cyborg and android shells housing the AI programming mechanisms. While scriptwriters might just as well regard their characters as puppets (they do, but dislike the connotations of the term) cinema deals with the physical realization of those puppets negotiating their in-world capabilities – what the Delos corporation terms 'livestock management'. If humans are cattle, then cattle are human: each can be steered through behavioural programming. Most importantly, Westworld allows 'character' to be nothing but a clustered blip of navigable posturing. In the desirous 'real-world' so cherished by cinema which champions 'real human drama' and 'stories that feel real', Westworld knowingly or unknowingly (the difference only matters to humanists) proffers 'character' as a post-human actuality.

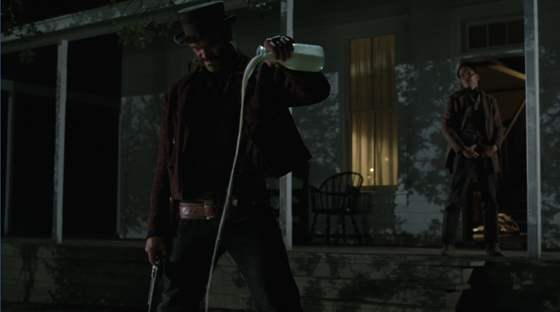

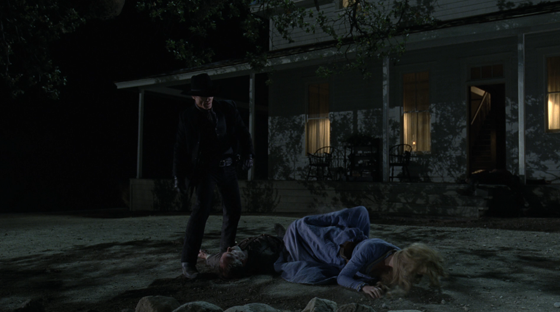

If Teddy and Dolores (she to a greater degree) navigate a complex Boolean map of responsive actions, the despicable duo they encounter upon their return to Dolores' family ranch home are oppositely written. Rebus (Steven Ogg) and Walter (Timothy Lee DePriest) have just shot Dolores' mother and are about to shoot her father Peter Abernathy (Louis Herthum); they are loathsome, amoral, soulless. The shadows they cast over their victims is a sign of their humanist absence. Less Goya's psychotic brigands and more Antebellum patriotic conscripts, they are doing only that which they are programmed to do: behaving like guests 'going straight evil', performing in-character to demonstrate the deeper/darker/more-real side of their bicameral selves. Tightly designed and scripted within reductivist psychosis parameters, their plastic presence is irrefutably 'evil'. Scriptwriters tag these type of characters as 'mono dimensional'. They're not: they're post-human, reduced to an essence and operating on a plane of compulsive nihilistic logic. Seeking liquor, they desultorily chug milk, spilling it down their front, spitting it on their victims, ultimately curdling it with their android blood once they are shot by the hero Teddy who metes deathly justice frontier-style. Their mechanized corpses lie in pools of milk, replaying the birth image of post-utero android fabrication detailed in the series' opening title sequence.

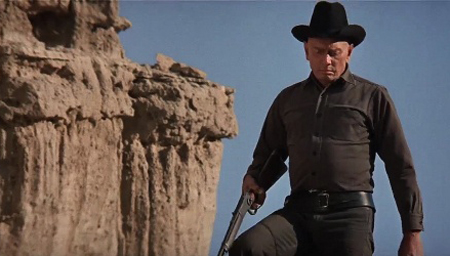

Following the carnage of this brutal revenge vignette, we audit Bernard in voice-over: "What if I told you that you were wrong, Dolores. That there are no chance encounters. That you and everyone you know were built to gratify the desires of the people who paid to visit your world." Cued to this intrusive voice-over, morbid plot threads are knotted: Freddy encounters Delores's dead mother inside the homestead; Dolores encounters her dying father on the ground outside; and Freddy confronts the Man in Black (Ed Harris) intimidating Delores. He ridicules Teddy as a cliched moralistic plot device, having him traumatically numbed by his inability to shoot the villain right in front of him. The Man in Black teases and mocks Freddy, informing him that his programming does not allow him to shoot guests. Freddy's confused face mimics the humanist who cannot acknowledge how inhuman people can be. Not only is the Man In Black meta-textual, he is also a disruptor to the Delos narration of Westworld. Amoral, asocial, unscripted and disbelieving, he is the cine-psycho returned to haunt the coddling narrative into which he has been inserted. Revisioning the original Westworld movie, he is the unpredictable human careening through the programmed android world, a polar opposite to the Gunslinger's (Yul Bryner) unpredictable android careening through the controlled human world.

As Westworld peels back its manifold layers in forthcoming episodes, the Man in Black is formed into a minotaur, desperate to escape the Delos maze he gazes into and demand who conjured him in a monstrous state. This is dark aspiration, where humanism will be a liability. His nemesis will be the supreme author Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins) who has spent his life constructing Westworld as a grand narrative designed to inter and entomb The Man in Black and any others who seek escape from their pre-designed reality. Theirs will be an Olympian struggle of authorship, waged between Man in Black's front-end incursions and Ford's back-end diversions. Westworld ultimately personifies its creationist drive through the omnipotent and omniscient figure of Ford. His character is modelled on the great American entrepreneurial industrialists (Henry Ford, William Randolph Hearst, Howard Hughes, Walt Disney, et al) in a mirroring of how populist tech-media deifies contemporary digital demigods (Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Bezos, Jimmy Iovine, Elon Musk, Palmer Luckey, et al). Yet the Man in Black's heroic arc - and Ford's heroic shielding - will be governed mostly by subterfuge, disinformation, fraud and betrayal. For what they mostly construct is a world of lies. Just like Dolores, Teddy, Clementine and Mr. Abernathy, they live their lie. It doesn't matter whether they perceive this or not, for the definition of a lying state cares for neither its recognition nor identification (hence the tech start-up demigods who believe their hype and author their marketing). The lies all Westworld's characters encounter are merely temporary barriers, suggestible corridors and trickster signage, which guide the characters' post-human unending egress.

If humanism is embodied by a belief in truth, post-humanism is liberated by a rejection of truth. And if humanist representation (in this case: distributed movies, broadcast television, VOD streaming, etc.) invites its audience to suspend their disbelief in order to be entertained, post-humanist representation that shares this terrain invites its audience to be like Dolores: to live the lie of her functioning dreamwork. Humanist art and culture prides itself on deliberating truthful states, especially by utilizing post-Enlightenment tools of rationalism to declare whether an artwork or artist is 'believable' or not. But such a self-congratulatory practice ignores a defining trait of humans: their capacity not simply to lie, but to believe, accept, suppress, and/or digest theirs and others' lies. If one momentarily accepts this, the contra-Enlightenment procedures of Westworld's narrative glint with sharp purpose.

Extending this, Westworld can be previsioned as a postulate of Nouveau Roman cinema, originating in post-WWII France and renowned for its disavowal of truth, fixity and clarity. In perfect service of this is Alain Robbe-Grillet's aptly titled The Man Who Lies (1968). Just as Westworld's textual moebius strips, fake iconic mirroring and short-circuiting character momentum render its interiority and exteriority in a state of simultaneity (courtesy of our analytic procedure enabled by the Lidar metaphor mentioned earlier), The Man Who Lies features a central character who (i) may or may not be lying, (ii) may or may not believe he is either lying or not, and (iii) may or may not be an interior character sealed in a hermetic narrative or an exterior author sealing himself into a textual narrative.

The film opens in a way that remarkably foreshadows Westworld's first episode. Boris Varissa (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is dressed in a 1960s suit and tie, stealing through a Slovakian forest, seemingly pursued by WWII Nazi soldiers and their Alsatian dogs. Shots are heard near and far; the soldiers are in search mode; Boris is in stealth mode. He eventually cuts a line across an open field. A loud gun shot is heard; Boris appears to have been shot. He falls to the ground; the camera moves up to him, closing in on his face. Boris opens his eyes and stares into the lens; the camera pulls back as he rises, dusts himself off and walks away as if nothing has happened. He arrives at a small village and relentlessly attempts to convince its inhabitants that he is a partisan from the war, and that he aided their partisan leader Jan Robin, whose wife, sister and household maid he fixates on, intent on proving the veracity of his story.

But prior to the plot commencing its multiple collapses into doubtful scenarios, the first lie encountered in The Man Who Lies is film language itself. Montage, sequential blocking and shot-reverse-shot are combined with continuous real-time aural atmospheres (wind, rustling, etc.), sound effects (on/off-screen voices, dog barks, etc.) and foley performance (foot steps, breathing, etc.) to imply that their audiovision is a given through its mimicry of spatio-temporal conditions for one's seeing and hearing real-world events and situations. Yet the modalities of sight and aurality are cleaved from each other in their technological reproduction: visual edits link temporal fragments of specific viewpoints to create a multi-perspectival assemblage of a spatial environment across fractured time; soundtracks are made of passages of recorded time whose duration does not equate the length of single edited shots, plus at any one moment there will be multiple layers of sounds occurring, each with their own orientation toward the sonic activity being recorded. Short of experiments in single-shot/direct-sound filmmaking, there is not a single facet of audio-vision's separation of the soundtrack from the image track that operates according to Euclidean physics of spatio-temporality in real-world events. All cinema is audio-visually Cubist; never is it 'realist'. Therefore, it does not matter whether the story appearing to unfold in the opening of The Man Who Lies is true or false. In fact, the core lie would be its attempt to convince us that it is telling us a truth - a feature of narration that all Nouveau Roman écriture critiques.

Such an epoch of intellectual jouissance seems far removed from our over-journalistic transparency-wishful present, where 'fake news' remains a topical issue as if there ever was such a thing as 'real news'. (Claiming that 'fake news' changes world events through manipulation is like saying only 'real films' reflect world events by not being manipulative.) Robbe-Grillet and his brethren of post-WWII intellectuals interrogated postures and claims of 'truth' not to promote grand narratives and pompous assertions, but because they were all affected by the deeper psychological battles waged across Europe between partisans and collaborators. The Man Who Lies is less an eroticised toying with identity in a decaying country house than it is floating law court of self-interrogation, where the partisan and the collaborator mirror each other in the manifold acts of lying they carried out as part of their wartime survival (partisans) and post-war prosecution (collaborators). If war is a dehumanizing spectacle - globally staged in WWII's far-flung theatres of conflict between Allied and Axis forces - then the post-war milieu can theoretically be regarded as a breeding ground for post-humanism. Exhausted, beleaguered, traumatized, numbed and emptied, the post-war self became a hardened shell whose only content was its registration of after-shock. In The Man Who Lies, Boris might be lying; he might be telling the truth; he might be incapable of telling the difference. Yet he remains strangely calm and disaffected. His mind-set is uncannily echoed in Dolores' acceptance of herself and her world. When pushed to query her existence, she responds like 'the woman who lies': "Every new person I meet reminds me how lucky I am to be alive, and how beautiful this world can be."

Finally, it must be noted that despite the conceptual treacle formed by this investigation into Westworld's potentiality as post-human post-cinema, the most important component in triggering this unreading is its superlative acting. An oft-neglected feature of Nouveau Roman cinema is the astounding veracity of the actors' performances, where they convincingly remain detached from yet convinced of the words written into their minds and mouths. Through a softly mannered performance of android-like consistency, they enunciate and articulate complex mind-boggling statements of existence, verbosely loaded and symbolically saturated yet disturbingly naturalised by the actors' commitment to their characters. Bereft of Brechtian distance, Expressionist caricature, Bressonian understatement or Stanislavskian method, they mostly act emotionlessly, indifferently, impassively. Let's call them 'textroids'.

Correspondingly, every time android Dolores opens her mouth - or we hear her ruminating off-line in voice-over like so many Nouveau Roman 'textroids' - she performs a similar feat of stupefying self-negation sans anxiety. To audit American films and television taking this on constitutes an unspoken radicalism. It has been brewing for some time in unplanned and unexpected areas – not in celebrated arthouse/indie triumphs of the human spirit, but in televisual serializations where characters are enveloped in deceit, duplicity and duality: e.g. Eastbound & Down (2009-13), Enlightened (2011-13), True Detective (2014-19), Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). Like Westworld, characters in these series block, detain or prevent simplistic readings of their motivation, as if we are like Bernard trying to read Dolores. Like deprogrammed androids, they behave erratically and unleash consequences which create circumstances which intensify their conflicted composure and impossible functionality. Psychosis becomes normalized through the actors remaining committed to the unspeakable and believing the unimaginable.

Superficially read as outré over-styled American entertainment populated with 'unreal' characters, these series collectively infer ways in which post-humanism can be digested and enacted. Their performers demonstrate how the 'shell' of a human is crucial to illustrate its nothingness and speak its unreadability. Westworld's cast are a pinnacle of this contemporary phenomenon. They populate the series' 'uncanny valley', typify HBO's agency, and reboot cinema as post-human post-cinema.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.