Review

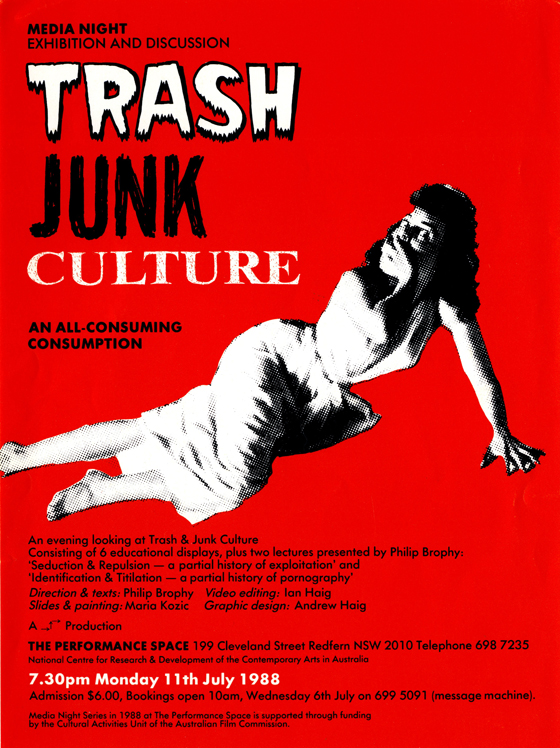

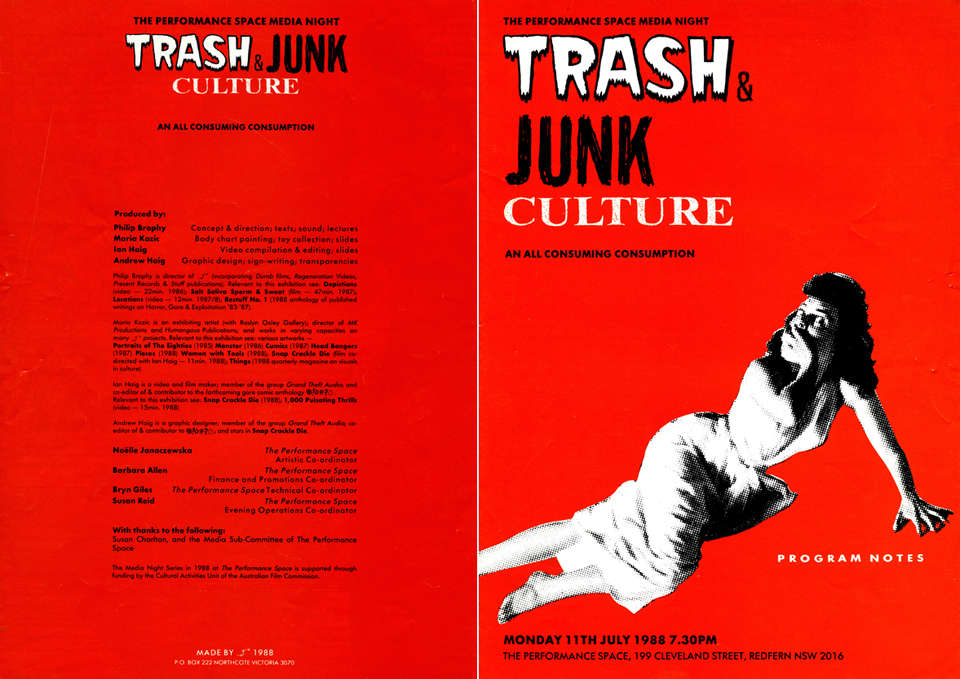

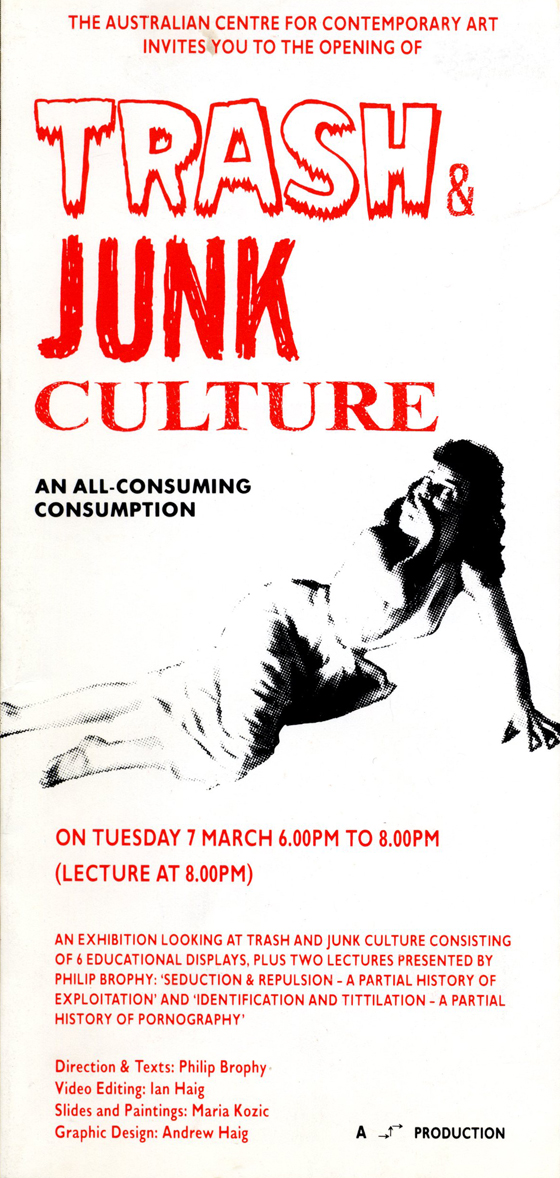

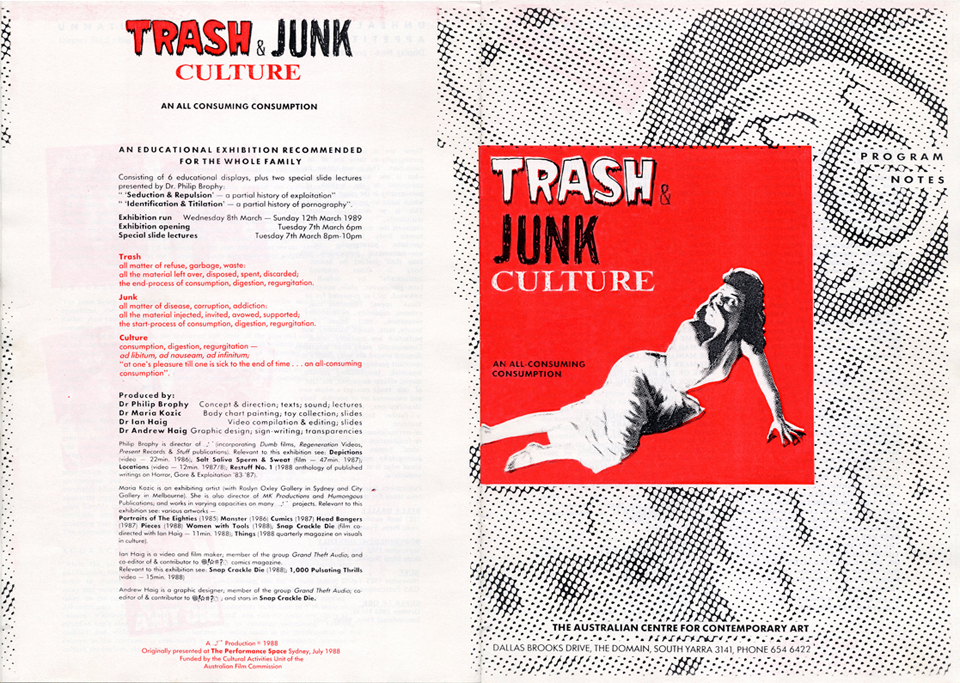

Trash & Junk Culture

published in Tension No.16, Melbourne © 1989

by Adrian Martin

There is a sense of humour inherent in the idea of an "educational exhibition on Trash and Junk Culture", but mostly - in the hands of Philip Brophy, Maria Kozic, Ian and Andrew Haig - there is a sense of purpose, curiosity, seriousness, pedagogy even. Why not be naturally serious about popular culture? All the minds in this area - from Robert Warshow, Lawrence Alloway and Nanny Farber to Raymond Durgnat, Dick Hebdige and Judith Williamson - have never been otherwise. But these days - the days of The Golden Years of Television, the Valhalla cinema and Beat magazine - there is an intense, horrid, pervasive pressure to reduce any thinking of engagement with popular culture to the knowing, flip experience of kitsch: cool guys and gals 'slumming it' in their memories of old records, TV shows, Hollywood movies. This is nothing much more than an indulgent but ultimately superior carnival of cultural recognition and ritual communal elbow-nudging: what fun! gross! how camp can you get? etc .... In fact, this reduction of popular art - art with (of course) as much intrinsic complexity, craft and cultural interest as any other supposedly 'higher' art - to 'pop culture' often proceeds via the rebaptising of this art as 'trash' or 'junk'. These words indicate all too often the flitting, condescending mind-set involved: what Meaghan Morris has called in another context the construction of 'mass culture as bimbo', the swallowing as 'lifestyle' of the worst alibis and ideologies of the leisure and entertainment industries.

In such a bimbo land, an educational exhibition on popular culture could only be a joke: for Brophy and Co. it is much more. And this has a lot to do with their conviction that culture, or life experience, cannot and must not be separated into ghettoes of, on one side of town, 'everyday' life with its innocent (or, for slummers, guilty) pleasures; and on the other side, 'directed' or purposive life with its serious pursuits (like studying for a university degree, or raising a family). It seems to me that anyone who, today, relies on this violent distinction of realms - whether the dandily kitsch lifestyler who begs to be left alone with his/her 'fun' culture, or the thundering moral aesthete who calls for a refinement of our battered sensibilities - is unfailingly and immediately conservative. Culture, as this exhibition suggests, is much more like a war zone, connected to all imaginable facets of life, in which one can grab tools, forge understandings, grapple with contradictions - in which one can dream and struggle. I doubt that culture was ever anything else. Of course, once understood in this way, there is nothing at all contradictory, hilarious or 'perverse' in wanting to teach or seriously discuss popular art. The only perverse - unnatural - idea is believing that one can't, or shouldn't.

The strategic and timely importance of this exhibition is to reclaim the words 'trash' and 'junk' from the kingdom of kitsch, and to deepen the useful meanings they do contain. For a danger of the popular-culture-as-art position (as a publication like the American Journal of Popular Film and Television continually attests) is the simple transposition of popular culture into the terms and cannons of middle class, high cultural art, so that one starts blocking out 'masterpieces' with 'mythic resonance' (Star Wars) or a superior modernism (De Palma): ultimately yet another elitist, aristocratic sorting of good and bad, quality and dross, us and them. Trash and junk, even in their most debased current usage, at least remind us of some of the key salient features of popular art: its vastness, anonymity, bitsiness, connectedness, disposability and ephemerality. Brophy and Co. set out to deepen our serious understanding of these phenomenological features.

The installation and its accompanying booklet constitute an intense exploration of the metaphors of trash, junk, and consumption as ways of describing the multiple workings of popular art. The spectacular flow of popular art, its speed and its 'surfaciality' (a favourite Brophy neologism) are stressed for the sake of this exercise in understanding (in another context, of course, one could as easily kick around the particular formations of 'resonance' and 'depth' in popular culture, or so I would hope). The key metaphors arrange themselves into various suggestive scenarios. There is, for instance, the enormity of the 'waste' or mess discarded by culture (and the fascination of this mess), in relation to the consumer's often awesome ability to 'swallow' it, to stretch and extend the consuming mind and body into new imaginative configurations (particularly vividly addressed in lan Haig's canny simulation of the 'ultimate compilation' of gory bits from horror movies). There are the official illusions of 'healthy', normal culture - warding off the 'sick germs' of low-class popular art - which turn out to be, from another angle, veritable maps of cultural "paralysis, constipation ... neurosis" in Brophy and Kozic's hilarious 'body charts'. The body is, indeed, another (perhaps the central) metaphor in the exhibition. From the wonderfully violent 'gross-out' toys for children (progressively outlawed in the marketplace) - Garbage Pail Kids in answer to Cabbage Patch Dolls - to the bewilderingly diverse variety of 'weird' erotic bodies in pornography, the Body assumes a central position as (in words from the booklet) "a symbol or metaphor for the ways in which life is lived ... representations of both the vulnerability and durability of ourselves". One could not ask for a more direct and engaged link between daily reality and the 'symbolic form' of an art.

A last bouquet. One of the most maddening and saddening aspects of the fun-fun-fun approach to popular culture prevalent these days - as much in a certain 'cultural studies' academy as in the weekly on-the-street rags - is the conjuring of the popular-cultural space as one completely without conflicts, without tension, without debate. In its way, this is a reflection of the consumerist fantasy of culture as a perfectly free-floating equilibrium of available commodities - constrained or arranged only by the consumer's free choice. (Frederic Jameson's idea of the post modern as the collapse of the distinction between high and low culture - by now in many places an unfortunate truism - has fuelled this fantasy.) This exhibition on trash and junk culture proffers a different, more antagonistic and dramatic notion. "While the art of culturing oneself implies methods of refinement, distillation and purification, there is also abrasion and aggravation involved in such an art ... Tension, conflict and violence then often become primary states in the development of any culture". It's good to be reminded in this way that the heat is still on.