Review

Apocalypse Near You

published in Real Time No.78, Sydney © 2007

by Darren Tofts

It used to be called the top. It was literally the end of the line for the tram service that snaked its way through the inner city to the northern suburb of Preston. The culmination of this journey was a terminus lined with shops, a place of conclusion and waiting, of browsing and purchasing. In Northern Void, a representative stretch of Plenty Road, Preston, is imagined as a vague, anachronistic time warp spanning a thousand years, where people still hang around the street outside empty and derelict shops, waiting for trams that never seem to arrive.

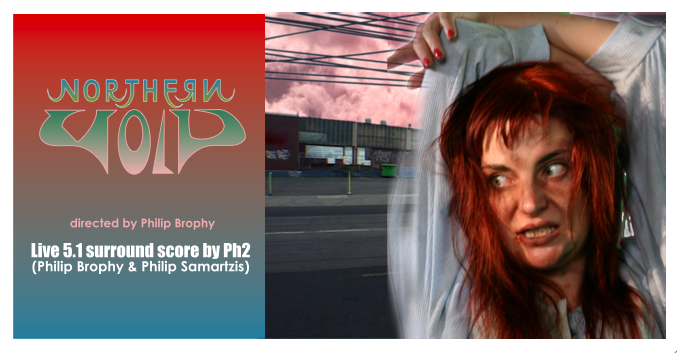

Northern Void ostensibly explores the notion of what suburbs might look like in the future. For Philip Brophy there is no such thing as the end of the line. Social and urban decrepitude, like rust, never sleeps and in Brophy’s universe the future ain’t rosy. Here is an anti-pastoral, dystopian world of breakdown and decline, where once thriving, reliable local shopping strips have yielded to the forces of time and the irresistible gravitational force of the mega-malls. Preston and its neighbouring Reservoir were once frontier suburbs, outposts of civilisation on the brink of the sprawling wastelands of rock and thistle that led the way to Sydney. Brophy’s northern void is not out there. It is the very fabric of suburban progress, a condition of place as much as time. Suburban corrosion is implosive, impacting inwardly as large centres such as Northland, offering glamorous ‘one stop shopping’ and ‘worlds of entertainment’, drew custom away from the archetypal “High” street. Since opening in 1967, Northland became an alternative place to hang out and by the early 80s the Top became a kind of fossilised badland, a ‘desolate plain’ that you passed through on the way to somewhere else.

The work is structured around a series of three stylised tableaux vivants, depicting the present (2013), future (2085) and post-future (3079). In each sequence the same strip of road and shop frontages is revisited, as if to chart the progress of suburban decay over time. We witness Plenty Road’s disintegration as a body slowly dying in a persistent future tense. Its zombie-like inhabitants mirror this dismemberment as they become ever more spectral, eventually resembling vapour more than flesh.

For me the least dramatic thing about Northern Void is its visualisation of what a post-apocalyptic world might look like in the next millennium. The present, 2013, looks uncannily like 2007. We are already the dead. The full-on compositing and digital effects of the third age strips out windows and leaves buildings barely standing as fragile shells. Harsh solarizing effects transform the sky into a sterile nothingness. These scorched and garish tonings may signify ‘the future’, but it is the unadorned photographic glimpses in the opening sequence that are more suggestive of the sedimentary quality of the street as an archive of past, present and future devastation. You can’t simulate that kind of brutality.

The repetitive, looping structure of Northern Void stands out as the work’s most remarkable and, for many viewers, troubling feature. Here is an unforgiving abstraction that tests the patience of its audience. Brophy never allows us to become complacent, to simply ‘get it.’ His vision of Hell resembles Dante’s: it is the tedium of repetitive cycles, rather than fire and brimstone, that torments protagonist and audience alike. There are also strong echoes here of Samuel Beckett’s more severe stage and video works, such as Play (1964) and Arena Quad (1980), which is included in the touring Centre Pompidou collection of video art, currently on at ACMI. In these arid, mathematically precise works, action is reduced to the serial repetition of minimalist gestures that don’t have any obvious reference other than relentless adherence to unseen and forbidding rules. We see this in the tics, abrasions and crutches of Brophy’s characters that, like those of Dante and Beckett, are indicative of their fall.

Northern Void begins and ends with swarms of bats and flying foxes, creatures of the night that see through sound. This is an apt framing device for a collaboration between Brophy and Philip Samartzis, whose sonic imaginations interpret the visual world through a mix of sampled, electronically produced sounds and natural and industrial field recordings. Performed live, the score animates the atrophying world on the screen, sculpting the theatre into an immersive audiovisual space of terminal conditions. My only criticism was that the amplification was no way near loud enough on the night. If I am to spend a season in hell, I want to feel it tear through every sinew. The live orchestral quality of Northern Void enables us to experience the visceral audiovisuality of the terminus as a state of things endlessly winding down. But be warned, it’s going to be a long wait to the top.

Northern Void

published in Paris Trans Atlantic February, Paris © 2010

by Dan Warburton

I reckon my bank manager would like a few words with Philip Brophy. It was thanks in no small part to his insightful writing on sound in cinema in The Wire a few years back that I started taking films more seriously than I had done previously, leading eventually to the DVD bulimia that has now taken over not only my life, but my wife's as well. Little did I know back then, when I read his superb essay on Walter Murch's sound design for Coppola's The Conversation, that Brophy was also a filmmaker and musician in his own right. In fact I only found this out a few weeks ago when five CDs on his Sound Punch label appeared in the mailbox. All of them are worth checking out, especially if you like a sideways view of intelligent techno (Beautiful Cyborg) and distinctly strange post-post-rock covers of Bowie's "Heroes" (Aurevelateur), but the one that's been getting the airplay round here is his collaborative soundtrack with another mighty Philip from Down Under, Samartzis (who, incidentally, took over from Brophy at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology).

Northern Void is a soundtrack – as well you might expect – for a 50-minute film of the same name Brophy shot in a disaffected industrial estate north of Melbourne. From what I can work out, Samartzis provided field recordings, and Brophy stuck music on top of (behind, underneath..) them. It's curiously haunting at times, even if the keyboards sound very keyboardy (if you know what I mean..) and even if the ear is drawn more into the background of Samartzis's field recordings than it probably ought to be. Brophy's knowledge of popular and not so popular music, from Ash Ra Tempel to Aphex Twin (via Jon Hassell and lots of early 80s synth groups you'd probably not mention in polite company) is impressive, but – perhaps because I haven't seen it in the context of the film, perhaps because Samartzis's sounds are so intriguing – one longs for a little more surprise, more dirt, more danger. What would Walter Murch have done in a disaffected industrial estate north of Melbourne, I wonder?