Processes & Considerations

Processes & Considerations

Record Production & Phonology

Developed for RMIT Media ArtsPROCESSES & CONSIDERATIONS

Many technical processes and professional skills make up the recording of a record. The term 'record production' essentially refers to the holistic organization of sounds in the recording process so as to document or 'realize' the event of the recording. Aspects concerning the production of a record include:

1. what equipment is used for recording the sounds

2. what instruments are played

3. how the instruments musically relate to each other

4. how the instruments are recorded

5. how the recorded instruments are treated in post-production

6. how the sounds of the instruments are made to relate to one another in the mixing process

Apart from the musicians, the people involved in the above steps would be:

1. the Producer - who functions somewhat like a Director in film, guiding everything toward an envisaged/pre-determined outcome;

2. the Engineer - who takes care of all the finer technical details - microphone positioning, level monitoring, effects-rack connecting, etc.;

3. the Mixer - who would be skilled in operating the mixing desk in the 'final mixdown', someone who would have a good sense of timing in 'riding' the levels of all the individual tracks as well as an ear for the precise combining of volumes and timbres; and either

4a. the Cutter - who is responsible for making the 'mother acetate' which is used for stamping the records out of vinyl; or

4b. the Masterer or Burner - who is responsible for transferring and compiling a finished digital master for encoding on compact disc.

The transfer from master tape to mother is crucial in retaining the overall presence and fullness of the original recording - particularly throughout the previous half a century of vinyl recording.

PERSONNEL

Aside from the above technical aspects, there are many musical considerations involved in the production of a record, which in turn define the different roles involved in producing the music - from its musical/emotional composition to its technical/material realization:

1. Composer - creator of the song/music in a writable state (ie. chords, melodies and lyrics, etc.) which can then be copyrighted and declared the work or intellectual property of the Composer.

2. Arranger - someone who takes those chords and its melody and decides upon a particular arrangement for its musical execution, sometimes involving the Composer as performer (with or without the 'group' that make up the identity of the performer) and sometimes incorporating a range of 'session musicians' (people who are subcontracted to play any music under direction).

3. Orchestrator - someone who is more involved in the technicalities of writing/transcribing musical notation (sometimes as directed by the Arranger, sometimes of their own accord) to match the required/specified musical arrangement, taking into account the capabilities of each instrument and how they could best play the arrangement.

4. Producer - someone who can be any combination of any of the above or none of them, but nonetheless someone who makes most of the decisions which will govern the sound of the finished musical construction (thus a producer can also be involved in aspects of engineering and mixing in order to more precisely control the sound of the actual recording).

EXAMPLES

Consider the following examples under these terms:

1. Presence - how near or far the central sound (voice or orchestral layer) appears

2. Interrelationship - the precise relations between the foreground and the background in terms of volume and separation

3. Definition - how clear the sound of the recording is; whether it allows a direct or indirect experience of the recorded sounds.

Voice

The Mormon Tabernacle Choir - STILL STILL STILL (55)

A tonal blur where male and female voices are fused; acoustic reverberation softens the overall outline of the voices; note the rupturing caused by their pronunciation of consonants like "s" and "t"; such choir recordings are sometimes recorded in actual churches or often simulate that acoustic environment in the recording process.

The Andrews Sisters - DRINKING RUM & COCA COLA (c. 41)

Exponents of the 3 or 4-part harmonizing which was popular throughout the 40s; note how the multiplicity of voices unifies itself into the one effect, and how those voices - as a thick yet sharp layer - moves on top of the orchestra underneath. The 'sound' of this vocal style is also the result a technical process: one mic for the singers which would pick up the orchestra playing behind them (not unlike radio technique from the late 30s/early 40s).

Judy Garland - HAVE YOURSELF A VERY MERRY CHRISTMAS (44)

A single voice on top of a soft orchestral backing; technique similar to the Andrew Sisters' example; note how even though the voice-recording is not hi-fidelity, it still retains and communicates the essential characteristics and nuances which code Garland's voice as 'expressive' of her particular style.

Lena Horne - BLUE PRELUDE (64)

Similar split between voice and/or orchestra, but note the sound of Horne's voice and how piercing it is; it almost sounds like it's feeding back on certain pitches she sings.

Judy London - IT'S A LONELY NIGHT IN PARIS (c. 59)

The mic type and positioning of this early 50s recording work to give London's voice the effect of being right up against the listener's ears; note how you can actually hear her singing at a soft volume - the recording conveys this effect while her voice performs it.

Harry Belafonte - FLOWER SONG (54)

Belafonte here is singing contrary to his husky Caribbean style, yet the recording technique also contributes to his operatic tone for this song; note how 'thin' the recording is, with little presence or dynamic range.

Cab Calloway - IT AIN'T NECCESSARILY SO (59)

An example of extreme dynamic compression, with Calloway's slightest breath being as loud or full as his highest shriek; note how it gives the effect of the voice busting at the seams, bursting out of the vinyl.

Orchestra

Glen Miller Band - STRING OF PEARLS & IN THE MOOD (40-42)

Radio recordings from the early 40s similar in process & technique to the Andrew Sisters and Garland examples; with a big band or small orchestra, the mic - for live sound or recording purposes - would usually be placed in close proximity to the conductor because the conductor is the central 'listener' to the music's combination; a recording of this type thus recreates the conductor's listening perspective; note how the soloists move up to the mic, while different sections (saxes, muted horns, etc.) will play their melodies by standing up on cue by the conductor - this serves to raise their volume level above that of when they are seated behind their music stands; note also the thickness of all the sound levels, produced in part by the complex harmonies and part by the single-mic technique.

The Ernst Maxim Orchestra - THE ROSES OF PICARDY (c. 60)

The string section of this orchestra is recorded so that one can only experience the 'mass sound' rather than hear it as single violins played together; the timbre and texture accented is the mass sound and not the individual instrument's character.

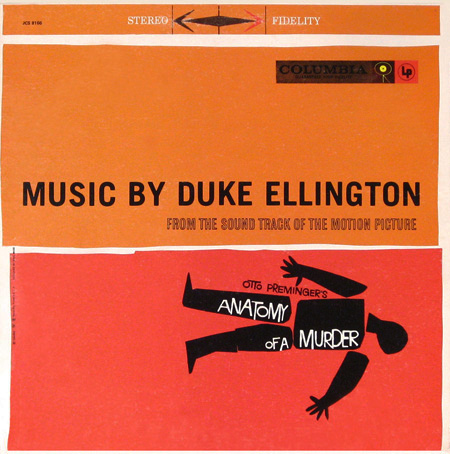

Duke Ellington - ANATOMY OF A MURDER theme & MOOD INDIGO (58)

Note how the full dynamic range of the orchestra is captured in the recording; the dynamics of the recording replicate the dynamics of the performance - listen to the clarity of the brass dissonance in "Anatomy" and the delicateness of the clarinet's key pads in "Midnight".

Fred Katz - HOW'S THE RAIN ON THE RHUBARB? (60)

Compare the mono-dimensionality of this recording of a jazz ensemble with the Ellington examples.

Hans J. Salter - SON OF DRACULA score (43)

Consider this mid 40s recording in comparison with the Glen Miller recordings and note how more depth there is in this type of score, which - due to it being a film score - is more generally experienced as a much more 'tinny' sound.

Jerry Fielding - POLTERGEIST score (81)

Digital recordings of orchestras such as this one on the one hand convey or represent the clarity and sharpness of timbrel presences of the instruments, but on the other hand the digital process captures the performance of the score in all its rawness - complete with wavering dynamics and a blurred precision in the dramatic flow of the music; these recordings of full orchestras are not unlike hearing an orchestra 'live' in that you experience the live event without any unification of its dynamics to translate it into the recorded medium.

Wendy Carlos - TRON score (81)

Note how Carlos combines his synthesized orchestral sounds with the modern/digital sound of orchestral timbres; the differences between the two are skillfully blurred.

Text © Philip Brophy.