Reviews

Hyper Material For Our Very Brain

published in Screening The Past No.36, Melbourne © 2013

by Eloise Ross

"Sonority does not inhabit language in quite the same way as the other perceptible qualities." (Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening)

Philip Brophy states at the beginning of Hyper Material For Our Very Brain that he is not concerned with himself, nor his audience, really; people are not innately more interesting than “things”. While this book proves that all of the “things” Brophy produces are indeed interesting, it does not succeed in proving the other side of his dictum, for Brophy is, of course, an invaluable source of interest. Of course, the audiovisual creations explained and analysed by himself and others, visually referenced in poster or still form, and announced on an accompanying CD, provide insight into his immense, and in some ways uncapturable, body of work. To some extent, Nancy is correct that language is insufficient to describe all of the euphonious, ephemeral elements of the sonorous realm, but Brophy certainly works his way around it quite well.

Hyper Material For Our Very Brain is a collection of and about Brophy’s work, an anthology marking his presence in the art and academic worlds. Perhaps a way to summarise Brophy’s approach to the place of his own work in the larger scope is by calling on a line by Darren Tofts, written in his essay ‘The Sound of Hair’: “Sound, along with its gestural manifestations in space as text and its organisation in time as music, cannot be controlled as it circulates through the airwaves” (27). Sound will circulate as it will circulate – sound enunciates along its own chosen path. Brophy, too, puts his work out there and allows it to do as it does. It speaks – or sounds – for itself.

Shihoko Iida writes, in her chapter ‘Performing Sex, Performing Gender’: “Gender can be considered a kind of desire that is far more instinctive than one’s given sex” (31). The book, the pieces written about him as well as those written by him, is defined by a straightforwardness that is an unfamiliar but welcome blend of unapologetic brusquerie, brilliance and absolute sincerity. It’s a snapshot of ‘sono-erotica‘ – a term Brophy uses to describe glam in his 2001 piece ‘Pale Glitter – Fat Sound’ (113) – it is music, it is image, it is the refusal-of-an-identity, and it’s about sound and the body.

Informative, dynamic, a whirlwind through the written and visual aspects of Brophy’s work, Hyper Material For Our Very Brain is heaps of fun. Just like Brophy’s view of the world, the book is 100% image and 100% sound, maybe just with 100% text added to the mix. This is like a tangible version of Brophy’s website, a barrage of coloured backgrounds, coloured text, eclectic fonts and headings – a trippy, chromatic adventure through Brophy’s brain, and into our consciousness. An interview with Brophy that opens the book is in blue text, articles by other scholars in black, and works by Brophy himself, to finish the book, are in bright red text, as though of the body and the flesh – his work intends to make us feel our bodies, after all.

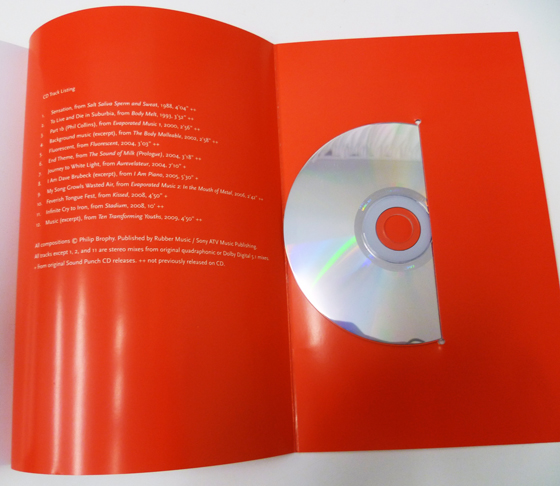

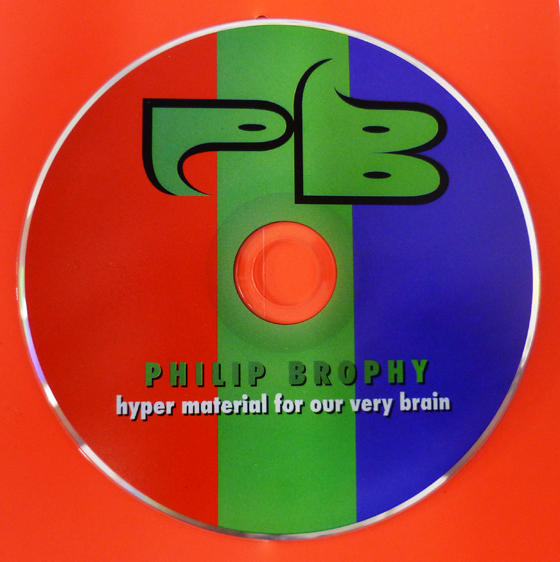

Without actually hearing, it is possible to be affected by the memory of sound as we read about it, if it recalls a particular experience or moment from our immediate or distant subconscious – and if the language is perceptive enough. Even with its powerful ability to affect us, it helps to have the real thing there, and how could we expect Brophy, master of all things art, to not treat us to something like this? An accompanying 12-track CD, with pieces, and fragments of pieces, conceived of and performed by Brophy over the past twenty-five years, allow the reader to become a listener, and to completely submit to awareness of the psychoacoustic and physioacoustic properties of listening. Brophy discusses these on page 115 in ‘Techno Collapse: Sound in the Age of Mechanical Malfunction’ (2003), which covers how the mind and body perceive sound both separately and together. I’m sure I have my own reasons for thinking that films, and specifically narrative films, are the best format to experience this, if we are talking about an art form that is outside of reality. But this quote from 1989’s ‘Film Narrative/Narrative Film/Music Narrative/Narrative Music’ – ‘Whatever your conscious mind thinks as it takes in a film, your unconscious body is taking it all in – in total, on the run, and while the film’s going’ (127) – suggests that film is the best, because it can capture the body so completely, from so many different angles of perception.

In an earlier article originally written for The Wire, which is not included in this volume but can be read on Brophy’s website, he suggests that John Cage operated in his own “anechoic chamber which excluded the world and its cultural noise”, and continues, in reference to Cage’s Speech (1955), that it’s a work that “sounds better on paper” than it “sounds itself”, “which is Cageian, I guess”, Brophy concluded. I had expected the CD to be cursed in the same way, given the coexistence of Brophy’s sound with image, but thankfully it is a good stand alone listen. It would be assisted, no doubt, by accompaniment from the visuals, but certain tracks – for example, ‘To Live and Die in Suburbia‘ from Body Melt (1993) and ‘Journey to White Light’ from Aurevelateur (2004) – are really enjoyable.

‘Part 1b (Phil Collins)’, from Evaporated Music 1 (2000), reminds me of Nancy’s discussion of physical sounds in his book Listening, where he designated sounds that refer to liquid, flowing, tearing, and rustling as sounds of bodily contagion, as the most evocative of tangible sensation. Chris Chang references this in ‘Text Will Eat Itself’, describing moments from Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat (1988), in which Brophy states, “Silence is dry. Sound is wet” (40). Sound is textural and enclosing, sometimes claustrophobic, and it washes over the body. As he has said elsewhere, he wanted to reinforce the continuous presence of the audience’s bodies, and of the body on film and in the soundscape. It is inescapable – very much so, talking about the CD. As an audiovisual artist, Brophy of course considers sound working best with the image and is opposed to the idea of separating them from each other, as they are in this publication. But there is text to consider here, too, which should provide enough to keep us going, in the meantime.

Brophy doesn’t hold back when he writes, or when he creates – it makes sense that Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Salò (1975) in particular, is one of his identified major influences. No part of this book is a compromise of his personality or his points of view. At times garish, always necessarily so, this is an audiovisual and audiotextual feast. This book really highlights the impact of sound on our lives, and on the importance of our bodies to all our experiences. These things are connected, of course – sound and the body – and Brophy connects to both intimately. Like Andy Warhol, whom the artist admires, there are many different kinds of Brophy, and each one lives through his different methods of Art. One would think, if Art is just shorthand for Artist like he and Andy Warhol suggest, then all of Brophy’s Art – this book included – is a stand-in for himself as Artist.