Catalogue Essays & Reviews

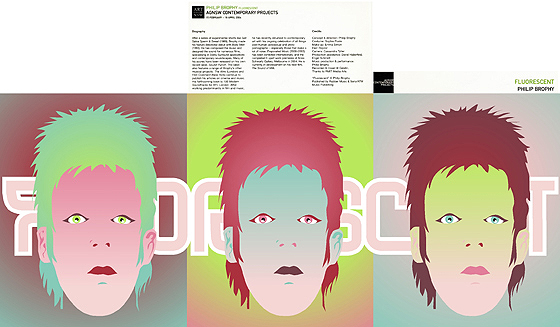

Fluorescent

from the Fluorescent catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © 2004

by Lara Travis

Fluorescent is really messed up. For Philip Brophy, who has cut a path by screwing with your mind, assaulting your senses and violating common standards of taste and decency, that’s a good thing. It’s not so much that he’s motivated by creating “shock.” He just likes things when they’re messed up, invalidated, confused, tainted, inverted, perverted - ¬stridently so.

This is the first conspicuously high-art project that Brophy has presented, in a long and prolific career that has produced music theory and criticism, cultural commentary, curatorship, two horror films, several albums, sound tracks and film clips. It is very much a high-art embodiment of a handful (of the many) long-term obsessions that he has; film clips, glam rock, sex and performance.

A Warholian understanding of the role of non-art objects being exhibited in the gallery context is a principal reason that Fluorescent consists of a video clip in an art gallery. Brophy says, “If I’m going to work in an art situation, I’m going put something non-art in it. It’s purely for clashing and contrasting. Not to upset anyone, not to create tension. It’s a Warhol thing, saying the right thing at the wrong time, doing the wrong thing in the right place. . . that always made sense to me because that means that everything’s always an experiment. . . . it’s pointing out the arbitrary, serial, modular nature of things: ‘ok this is the context, so let’s chuck that in.’”

The film clips that Brophy is referring to are early eighties, first wave MTV film clips when they were a relatively new genre that had no status as such in the realm of visual culture. To Brophy these film clips – Cyndi Lauper, early Madonna, Twisted Sister - are directly opposed to the nineties productions, by which time they had become a respected art form with big budgets and high production values. He likens early 80’s film clips to screen prints insofar as Warhol appropriated the latter for their evocative qualities as an “invalidated” cultural form.

Even in those film clips, Brophy finds a visually and aurally promiscuous, amorphous nature; a willfully or not ‘wrong’ quality that frequently emerges in his work , “. . .early MTV was so reviled . . . but to me it was like THAT’S POP, THAT’S REAL POP - this totally trussed-up, dressed-up pseudo-glamorous fictitious presentation of pop music in an audio visual form; ripping off television, ripping off cinema, ripping off anything to create a spectacle. Cinema in the early 80s was not necessarily spectacular; where as video clips took the energy of music and spectacularised it. In the process they degenerated cinema, which I really liked the idea of.”

Philip Brophy’s universe is really a soup of impulses and drives, images and sounds. Regardless of whether he is looking at film, music, film clips or art, he brings to any subject an acute sensibility. He is incredibly well organized as the alphabetical and thematic organization of his record collection attests. He has a facility for theory and finds analysis and thinking “more fun than football.” However, despite a cerebral inclination that has seen him previously labeled as analytical, cold, and intellectual, he is preoccupied with the most material of phenomenon. If it splatters, bleeds, oozes or explodes, Philip is interested. If it (whether “it” is a film, a sound, an image, substance, person or object) degenerates and corrupts other entities, infiltrates their boundaries and buggers them up, even better. He has love of the fake and flamboyant, the self-consciously invalidated. If there were no categories, boundaries or prescriptions, Philip Brophy would be in heaven but he would also be out of a job. So his reason for choosing Glam as the genre for Fluorescent is an attraction to it’s sexually and visually amorphous qualities, its aberrations of gender and its traceability through so many other cultural forms. He chooses Glam,

“. . . because like video clips, like horror, like porn, it’s a genre trajectory of a bizarre substance that carries through a long way, like a potent smell. It’s in lots of things and it really goes places. Like horror: to me it’s is this incredibly potent thing. It is THE THING: it’s the nameless, it’s everything you can’t even say is the Other. It’s beyond the Other, like sex turned inside out. It’s the materiality of the world, kind of Bblllaaaahh - your covered in it. And no other genre of cinema does that. Romantic comedies don’t do that; action movies don’t do it. Glam is like a form of rock which is antithetical to rock.”

Rock is in contrast, authentic, real, masculine and authoritarian. “’It’s the ground mate; it’s solid.’ Rock is a guy standing with his legs apart saying ‘I own this fucking earth’ - and all that gender bullshit. ‘This is real fucking rock, this is the real music.’ Glam comes along and it’s like ‘ ‘daaahling!’ It fucks with those very people because glam never matched; it never fit, it was always out of place. It’s that recurring out-of-placeness.”

The artificiality and perverse sexuality of glam was as much a mirage as rock n’ roll’s machismo. After all David Bowie just kissed Lou Reed for the publicity. And it’s not so much that the invalidity of glam rock was fundamental. It’s one of the greatest phenomenon of late 20th century music and everyone knows that Bowie is the master. This is more about what Glam posed as, in a spectacular, self-conscious and thoroughly artificial way.

So if Glam is not even real at being Glam, even better. Brophy says, “ … the posing I kind of like. I like anything that’s a lie, that’s fake that’s artificial, because it’s not then attempting to break my balls with being the truth. The one thing I am not interested in anyway is the truth of a matter. What is ‘the truth of a matter’? I’m like: fuck the real you! That’s so lumpen and orthodox and returning-to-home-base. And with glam, the open fakery has always been an impressive thing to me.”

That said, an awareness of personal content in his work is creeping up on Philip Brophy For example in his 1988 film Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, “The guy dies at the end and I post-dubbed the sound on that scene. That is me re-performing when my father died of cancer. I remember it dawned on me when I was doing the scene: ‘I’m now restaging my old man fucking dying of cancer, complete with a death rattle’. But I didn’t present such things as personal signifiers because I totally disbelieve that notion that you should put yourself in the work. If I felt that there was an emotional mood or a bit of me coming out in the work, I would clamp it in all sorts of ways. But after Salt Saliva Sperm and Sweat, which is such a ‘high art intellectual’ movie, I realized that everything in that movie is one hundred percent personal and one hundred percent me.”

Thankfully, this discovery is qualified by a healthy cynicism about personal expression in art and music. “It’s like again a Warhol thing, I always liked that Warhol was considered as impersonal, cold but everything he was into was right there in the surface.”

Fluorescent has taken Brophy out of the commentator’s role. Like his music criticism and even the recent video work “Evaporated music,” his work has typically been about presenting work made by others in a very particular way. In Fluorescent, the genres of glam rock and the music video clip give Brophy an opportunity to “openly create a self.” The operative word here is “a” self, not “myself” or “oneself.” That is the meaning of Glam in this work in relation to identity. Glam was not about discovering your true self, it was more like, “I wanna try someone on.”

Fluorescent

from the 1st Singapore Biennale catalogue, Singapore © 2007

by Russell Storer

Philip Brophy's Fluorescent (2006) is a music video, starring the artist himself as the embodiment of a Glam Rock hero: the sexually slippery icon that turned macho Hard Rock on its head in the early 1970s and never looked back. For Glam was about the future: a glittering, tin-foil future of space travel and fluid identity, where anyone could fly to the moon or be a star, as long as they had the right outfits. Glam's celebration of surfaces prefigured the explosion of music video in the early 1980s, a form that experienced a brief flowering of intense, raw-edged creativity before sinking into a generic soup of expensive effects and glossy marketing campaigns. In the spirit of this early moment, Brophy's pop star is riotously rough, favouring pancake make-up over airbrushing and swagger over choreography.

Driven by throbbing surround-sound and split across three screens, Fluorescent plays with the crucial yet awkward relationship between music and image. Featuring both the full mix and remixed versions of the song, the work severs this connection at several points when the sound drops out as the video performance continues, throwing a focus onto the elaborate artificiality of Brophy's act and the constructed-ness of our aural and visual perceptions. A widely published writer and theorist on sound and cinema as well as a film-maker and sound artist, Brophy encourages one to 'think with one's ears' when watching a film to appreciate the sensory and psychological properties of sound, transcending its generally conceived supporting role to the image.

Fluorescent also derives from Brophy's long-held fascination with genre-busting cultural forms — manga, horror films, Glam, pornography — as well as their insidious influence, seeping into and transfiguring so-called 'High Art' and popular culture alike. Each form stretches or dissolves the body in one way or another, reducing it to an amorphous, polysexual entity that defies easy categorisation and forces a reconsideration of our own drives and mortality. From his early short films such as Salt Saliva Sperm and Sweat (1987) to his horror feature Body Melt (1993) to his ongoing series of pop video 'interventions' in Evaporated Music Brophy has pulled the body apart to reveal its bare, brutal essence, removed from comfort and civility. He shows us the body as an abject, desiring machine, yet with its own horrific beauty.

History's great escape

published in Real Time No.60, Sydney © 2004

by Daniel Edwards

An eternal present, an absence of memory and a dissociation of words, symbols and images from meaning: these are the symptoms of the ‘schizophrenic’ social condition diagnosed by Frederic Jameson in his 1983 essay “Postmodernism and Consumer Society” (Hal Foster ed, The Anti-Aesthetic, Bay Press, Seattle, 1983). Twenty years on Jameson’s diagnosis has even more credence, so it is no surprise to find 2 recent installations at the Art Gallery of New South Wales responding to this aspect of contemporary experience, albeit in very different ways.

Sound artist, filmmaker and writer Philip Brophy pays homage to the androgynous theatricality of early 70s glam rock with Fluorescent, comprising a circle of 5 speakers in front of 3 simultaneous video projections. Ever-changing lines of colour play across the screens, bringing to mind the video clip for Plastic Bertrand’s 1978 pop classic Ca plane pour moi. Brophy periodically appears out of this swirling matrix sporting spiked hair, thigh-high shiny vinyl boots and a ball-hugging leotard. He mouths a few risque lines before disappearing, until the backing band kicks in on his fourth appearance and he performs a specially-penned glam rock anthem.

The various tracks that comprise the song are separated across the ring of 5 highly directional speakers, which means the song sounds quite different depending on where you stand in the circle. The extreme separation between the sonic components of the soundtrack highlights the self-consciously manufactured nature of Brophy’s “Fluorescent” persona. The overall effect is of loud, vulgar, theatrical fun, and many viewers burst into spontaneous laughter at the sight of Brophy’s gyrating, larger than life form.

Glam was always about celebrating the brash disposability of pop culture and the performative aspects of identity. In this sense, Brophy’s work doesn’t do anything that glam itself didn’t do in the early 70s. But he takes familiar iconography and places it in a gallery setting, creating resonances beyond the world of popular music. Glam here is no longer a knowing reconfiguration of existing images from the realm of popular culture, but rather a trope unto itself that has entered the infinite matrix of images comprising contemporary experience. Brophy’s joyful performance celebrates the arbitrary recycling of the past and the freedom of employing symbols and icons divorced from their original context and meaning. (...)

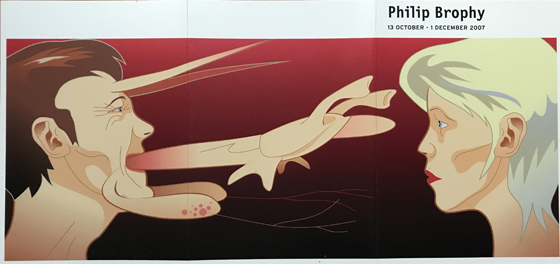

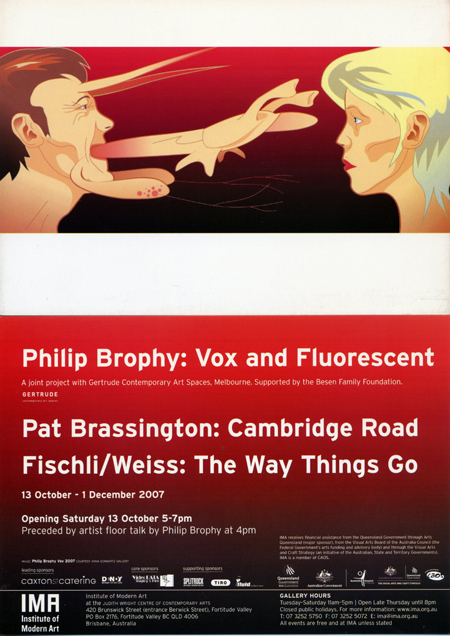

Philip Brophy: Dissonant Juxtaposition and Poetic Estrangement

published in Broadsheet Vol.36 No.1, Adelaide © 2007

by Sean Lowry

(...) On a different tangent, Fluorescent 1 (2004), a three-screen installation commissioned for the Contemporary Art Projects at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and later exhibited at the 2006 Singapore Biennale, features the artist as a simulated sexually ambiguous glam rock icon. As Brophy struts across three giant screens singing lyrics that exemplify glam’s narcissistic celebration of androgynous polysexuality, he highlights the brash disposability of pop culture and once again demonstrates just how skin-deep our acceptance of the pretence of identity or style actually is. Although Brophy positions identity as a recombinant reiteration of pre-existing symbols and styles, his simulated pop star, from its awkward movements to its camp make-up, is certainly far trashier and unforgivingly human than the carefully airbrushed, choreographed and sanctioned rebellion or neatly gendered sleaze found on post-millennial MTV. For Brophy, glam’s collision with the warts-and-all lighting and embryonic production techniques of 1970s television resulted in a far more confronting and abject display of ape meets sci-fi glamour than its contemporary stylised and regendered incarnations.

Again using surround-sound and split image formats, Fluorescent teases out the often arbitrary, yet sensationally omnipresent relationship between image and sound that defines popular cultural landscapes. This arbitrariness is further exemplified by the occasional sound lapse within the ongoing video performance, begging the question; is the fictionality of the image more or less evident without its constructed audio accompaniment? Also, in separating the various tracks that comprise the song across the full Dolby 5.1 experience, significantly altering the way that one hears the piece in different parts of the room, Brophy both simulates that raw warts-and-all, sweaty beaded makeup and awkward nakedness of a 1970s glam television performance, and at the same time takes full dimensional advantage of twenty-first century technology. Although relatively quickly dismissed as a gimmicky smear on the face of pop culture, glam rock’s legacies, via the process of historical retrospection, have been brought alive again and again. Given that issues of race, class, gender and sexuality coincided with both the rise of video technology and the evolution of installation and performance based artistic practices, it stands to reason that the subject of the body remain so inextricably linked to contemporary video, performance and installation based new media arts. (...)