Evaporated Music 2

Catalogue Essays & Reviews

Biomorphic Horror

published in Artspace Projects 2006 Artspace, Sydney © 2007

by Tanya Peterson

"The only way we can make contact with each other is in terms of conceptualisations. Violence is the conceptualisation of pain. By the same token psychopathology is the conceptual system of sex." [1]

In JG Ballard's The Atrocity Exhibition, subjectivity comes across as a little bit flat in more ways than one. Identities are assigned to a set of default images that circulate in the ether of capitalism. Here, subjectivity is performed as a kind of psychotic mimicry, where bodies move and feel in response to the media spectacle of their own depiction and consumption. Experience no longer maintains a close proximity to sensation, and affective distance is subsequently misread as (consumer) desire. At best, selfhood is characterised by a marketable indifference, like the ideological 'essence' of a trademarked product. This is the conceptualisation of a corporeal reality - an ironic transformation of flesh hypnotically yielding to the reification of its own image.

Biomorphic horror occupies a slightly different realm of somatic estrangement. It is the recognition of these confused boundaries within a far more visceral domain. This type of horror occurs when the sublimated line between the body and its market double is wounded, like a temporary glitch in the economy of the commodity fetish. Bearing witness to its own alienation, the subject's body is glimpsed as a surplus by-product of its commercial counterpart. This is the horror of an abject recognition, the process of the body becoming other, becoming image. When the physical limits between the subject and its representation are unclear, the body is suspended between the languages of signs. During this transformative state 'identities (subject/object, etc) do not exist or only barely so.' [2]

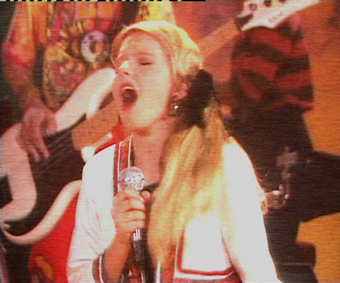

This anxious coexistence between the body's visceral state and its dissociative narcissism also manifests itself in Philip Brophy's multimedia work Evaporated Music 2: At the Mouth of Metal (2006). In a darkened room, a high definition television is hooked up to a Dolby 5.1 surround sound system. Playing on it is a short, looped excerpt from the 1990s teen television series California Dreams. In this clip, the young male and female lead cast perform as members of a high school rock band, while an enraptured audience of students and teachers watch with approving discernment. The song the group plays, however, is deliberately off-key in relation to the image projected by these synthetic small-screen stars. Rather than the innocuous bubble-gum sound of teenage pop, Brophy has dubbed the performance with a death metal anthem, which the band appears to grind out with angelic commitment. Painstakingly synched up to match the mouths of these readymade innocents, the audiovisual dynamics thus serve to both cohere and paradoxically split the subjects' on-screen personae.

In Evaporated Music 2, Brophy uses mimicry to induce a state of biomorphic horror similar to that described by Ballard. This occurs at a number of different levels within the work, primarily at the mouth's threshold. The widescreen television is the first orifice to draw attention to itself in the seedy darkness of the installation space. Sitting opposite a roomy black leather couch, it bleeds a cycle of images on the verge of decomposing as they pass through the sanitised threshold of populist entertainment and into the ersatz living area of the exhibition. Sounding the death knell of repression, the metal soundtrack transforms the oral mimicry of its pop vocalists into a performance of abjection. A primordial sound is discharged deep from within these teenage bodies, as the key lyrics of the song's chorus 'my song growls wasted air' articulates the vocal range of the performers. In this world, the air is rotten and empty, its freshness having expired long ago in the mouths of animated pop culture cut-outs, who sing and perform on a stage as artificial as the show's prefabricated plots.

One of these steps involves Brophy miming his newly composed song while scrutinising his reflection in a mirror, in order to assess the 'labial confluence' of the lyrics. [3] These oral acrobatics ensure that the initial California Dreams performance visually matches his new vocal mix. This is a process of musical evaporation, where the seemingly wholesome (read ideological) ingredients of the original song are dispersed. What is left is an aural derivative (metal music), a thickened remnant of its 'natural' source. The condensed music, once mapped over the mouths of those prime-time adolescents, assumes a type of fleshy materiality as the force of the surround sound resonates deep inside the viewer's own body. The reverberation pushes against the grain of social commodification, leaving the body (both on and off-screen) in an awkward embrace with the perverted excess of its artificial other. Brophy situates the self-reflexive experience of biomorphic horror as a form of affective liberation, using it as a subversive tactic where sensation has the ability to short-circuit the logic of late capitalism. Overall, the cumulative effect of his orchestrated ventriloquism exposes the pathology of mimicry within commercial culture, and presents us with the disturbing image of subjectivity as the conceptualisation of psychosis.

A transgression of subjectivity is further at play behind the scenes of the featured video. In order to create these monstrous effects, Brophy undertakes numerous steps in the reformatting of the work. Brophy's sampling of pop culture offsets the uniform consistency of the status quo with its transgression, a wavering between repression and parodic anarchy. The dualistic nature of this experience is enhanced through the set-up of the exhibition. The couch and television are there for a reason. Instead of a large projection and a walkthrough viewing area, Brophy creates a space that blurs the distinctions between a studio set and a family living room. It is a set-up that we are isolated from, yet at the same time belong to, and culturally invest in — the facade of a cosy ambience that has come to stand for intimacy in so many family homes. From within this domesticated zone of alienated comfort, watching Evaporated Music 2 is a little like watching Sam Raimi's slapstick gore-fest, Evil Dead 3: Army of Darkness (1992). [4] There is a certain pleasure in the shock of horror when it reaches the level of farce, particularly from the pseudo-safety of a living room couch. Feeling protected by an invisible force-field of familial ideology, we are free to partake in the fascination and depraved delight one gets from watching the vacant allure of robotic kids who are forced to repeatedly peddle a message of nihilism with saccharine intent.

At the level of conceptualisations, a parallel could also be drawn between Brophy's work and the films of Andy Warhol. Steven Shaviro has used the term 'conceptual pornography' to describe the viewing state that is ultimately solicited by Warhol's films.' For Shaviro, Warhol's films enter provocatively into the economy of pornography due to their ability to incite 'titillation' and 'boredom' at the same time. This effect is achieved via an overt presentation of the performing body, which blatantly gives itself over to total voyeuristic access. In particular, Shaviro stresses the 'physiological' primacy of Warhol's films and their immersive ability to saturate the viewer with a spectacle of fetishised effects. Shaviro argues that these seduction effects are so ordinary in their cliched predictability that they produce a similar level of indifference in the viewer — a spellbinding monotony that fixates the viewer's gaze. Brophy's work offers a similar scenario of formulaic enticement, where boy-gets-girl through a combination of song, an amorous exchange of looks, and the choreographed subtlety of a few hip gyrations. Cut in the style of an MTV video clip, its compressed narrative runs on a simulated cycle of seduction, where the promise of arousal is realised all too soon in a stale climax of full disclosure.

Evaporated Music 2 positions us within the seemingly safe domain of domesticity, only to violate our regulated pleasure by showing us its obscenity. The exploitation of biomorphic horror within this work reveals a society where identity has become a pornographic caricature verging on the point of normality. The upside, however, is the humour that comes from these exaggerated feats of untenable compliance overwhelmed by the collective idealism of the mainstream. With a winking playfulness, Brophy's work leaves us with the contradictory logic of rationalised insanity. It tempts us with the possibility of madness beyond the mouth of commercialised banality-a madness where the body is free to exist in all its grisly beauty.

Notes

1. 'Biomorphic Horror' is a term coined by J.G. Ballard as a signpost for this definition in: JG Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition, Flamingo, London, 1969, p. 116. This concept is pursued widely through a number of novels by Ballard, most recently in: JG Ballard, Kingdom Come, Fourth Estate, London, 2006 (see especially p. 147).

2. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, Columbia University Press, New York, 1982, p. 207.

3. Philip Brophy, Evaporated Music 2: At the Mouth of Metal, exhibition room sheet, 2006.

4. The title of Brophy's work can also be read as an allusion to John Carpenter's horror film In the Mouth of Madness, 1995, which is loosely based on H.P. Lovecraft's novel At the Mountains of Madness, and other novels, Victor Gollancz, London, 1931/1966.

5. Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis/London, 1993, pp. 236-7.

Evaporated Music 2: At The Mouth of Metal

published in One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne © 2000

by Kara Reeves

(...) The ubiquity of reality television and 'star search' programs has convinced society that fame is within the grasp of everyday people. Popular television comes under scrutiny in work by Philip Brophy as well. An on-going and multifarious project, Evaporated Music 2 - At the Mouth of Metal (2006 + 2008) continues and extends his 'aural surgery performed on the audiovisual skin of mainstream iconic videos' initiated in Evaporated Music 1 (2000-2004).

Appropriating found footage, Brophy feeds his audience familiar sanitised television programs, with selected scenes from popular family-oriented TV series in which manufactured, sickly-sweet teenagers perform in pop-rock bands. With careful observation he re-writes the lyrical content — with words that, when lip-read closely resemble the originals — whilst also transmuting the musical component. As the teen actors open their mouths, they are reduced to self-parody. A cacophonous rendering of this synthetic opus reduces it to doggerel, disturbing the visual environment and subverting stereotypes and codes. In a battle between good and evil, pure and corrupt, Brophy strips them of their squeaky-clean image, as the antithesis of their saccharine sound emanates all around in Dolby Digital 5.1 surround sound. His new compositions and voiceovers transform the pop plasticity into dark, heavy metal filth; upturning the world of vacuous televised pop, and revealing a dark underbelly throbbing with prime evil. Like Sandra Dee with Tourette's — "Lap dance choking whore" spills out with a smile. (...)

Philip Brophy: Dissonant Juxtaposition and Poetic Estrangement

by Sean Lowry

published in Broadsheet Vol.36 No.1, Adelaide © 2007From his early experimental deconstructed disco and reconstructed soundscapes, to film scores, Japanese styled anime, re-scored rock video clips and audio-visual installations, Melbourne based artist Philip Brophy specialises in twisting the culturally familiar into the strangely unfamiliar. With an already well-documented practice now stretching over three decades, from early collaborations such as experimental group → ↑ → , to film projects such as Salt Saliva Sperm and Sweat (1987) and Body Melt (1993), to more recent pop video mutations such as Fluorescent 1 (2004) and Evaporated Music (2000–), to his first interactive installation The Body Malleable (2004), Brophy has consistently intersected themes ranging from pop, rock, sex, anime, exploitation, monstrosity and gore within a remarkable range of audio-visual incarnations. In an era already gorged with myriad hyperbole and rhetoric surrounding interdisciplinary practices, Brophy has consistently produced curious mutant variations of popular cultural formations. Somehow, Brophy manages a collusion of the attitude, humour and theatrical vulgarity of rock and pop culture’s many splintered sub-genres within the drier reflexivity of contemporary art without diluting the potency of either. Given the span and diversity of Brophy’s practice, this text will focus primarily upon Brophy’s most recent audio-visual installation practice, in particular Evaporated Music 2: At the Mouth of Metal, exhibited at Artspace, Sydney in 2006, Fluorescent 1, a three-screen installation commissioned for the Contemporary Art Projects at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney in 2004 (and subsequently exhibited at the 2006 Singapore Biennale) and The Body Malleable, an interactive quadraphonic digital animation commissioned by the Cinemedia Digital Media Fund in 2002, first exhibited at Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image in 2004, and most recently as part of the Anne Landa Award at the Art Gallery of NSW (2006).

For French critic Nicolas Bourriaud, ‘style’ is now determined by “ability to inhabit an open network).” [1] Brophy’s ‘open network’ generates fluid relationships between pre-existing media, programmed scores and the installation of projection and surround-sound technologies. As with much contemporary digital (or so-called new media art), emphasis is typically less focused upon the specific origin of the imported fragment but rather on its subsequent translocation and manipulation. According to new media theorist, Kevin Robins, digital technologies place the nature and function of representation even further in doubt than mechanical reproduction, for “digital information is inherently malleable”. [2] Brophy’s imported fragments can range from whole video tracks to stylistic inversions of glam or manga surface, whilst his range of intervention ranges from technical manipulation to strategic exploitation of the dissonant yet poetic relationship between radically juxtaposed elements. Given that the expressive language of reconstructive sampling has largely overtaken ironic strategies of appropriation, new meaning is typically located in the poetic translocation of pre-existing signifiers. Gradually, as quotation and repetition become habit, they become the foundation of new forms of creative expression, whose trajectories have their beginning and not their end in ironic or apocalyptic estrangement. For Bourriaud, artists are no longer “creating meaning on the basis of virgin material”, but rather “finding a means of insertion into the innumerable flows of production”. [3] Ultimately, “the artwork is no longer an end-point but a simple moment in an infinite chain of contributions”. [4]

According to the late Australian critic, Nicholas Zurbrugg, although contemporary culture can be considered in many ways “apocalyptic... superficial, weightless (and) static”, it is nonetheless finally capable of functioning more ‘profoundly’, ‘weightily’, or ‘radically’ when considered against “the complex creative potential of its ever-evolving technology”.5 Brophy recognises that production methodologies are invariably experimental by consequence not design. As a consequence, he does not present the capabilities of technologies that he uses for their own sake. Rather, he employs technology in order to engage in contemporary cultural dialogue (which is of course highly technologically dependant). Brophy is as much a consumer as he is a producer of sound and image. Ultimately, both the meticulously composed original scores and the wholly appropriated or prosaic fragments in his work perform an equivalently meta-aesthetic role within the poetic whole. An archetypal ‘prosumer’, as foreshadowed by Marshall McLuhan, Brophy acknowledges that the strategic music producer is by default also a music consumer.

The first installment of Brophy’s pop video mutations, Evaporated Music 1, exhibited domestically and internationally between 2000 and 2004, utilised found footage of familiar pop icons and transformed them into unfamiliar noisemakers. In a world in which most of the raw materials of culture are privately owned, high budget music videos by Elton John, Billy Joel and Phil Collins, Gloria Estefan, Celine Dion and Mariah Carey were projected unedited, the original sound track having been replaced by eerie abject gasping vocals and commandeered distorted sounds in full Dolby 5.1 surround-sound. Here Brophy’s constructed alien cinematic sound design appeared to synch with every on-screen movement, and consequently, the viewer’s expectations of pop culture’s generic audio-visual synchronicities were hilariously dislocated.

Brophy’s Evaporated Music 2: At the Mouth of Metal (2006) takes this idea of dislocating generic audio-visual synchronicities one step further. At the Artspace installation the viewer was greeted by an inviting black leather couch and a DVD displayed on a widescreen TV with Dolby 5.1 surround- sound. Utilising a pirated live band performance from an early 1990s TV show called California Dreams, Brophy has synched a specially composed death-metal track complete with lip-synched lyrics to the existing mouth movements of the on-screen performers. For Evaporated Music 2, a range of appearances by ‘fake’ bands consisting only of actors on TV shows such as California Dreams, Saved By The Bell, The Incredible Hulk and CHiPs are rescored with metal music to match the performers movements and vocalisations. Part A–California Dreams (My Song Growls Wasted Air), is the first instalment in this series, and introduces popular culture’s most demonic ‘other’, the deliciously throbbing sore that is death-metal, to perhaps its the most G-rated antithesis possible. Paradoxically, it is the healthy, racially diverse and squeaky-clean California Dreams that actually starts to resemble a corpse once the installation comes alive to the throbbing relentless barrage of quadraphonic death-metal.

Although, in and of itself, the unaltered reuse of an entire saccharine sweet rock performance (complete with network watermark) from a family orientated TV show might initially remind us of Pictures generation artists Richard Prince or Sherrie Levine’s ground-zero strategies of collage (or rephotography) of the late 1970s and early 1980s, but such a comparison quickly pales once we absorb both the complexities and poetics of such a dissonant audio-visual juxtaposition. In erasing the ‘original’ music and substituting a specially programmed and perfectly lip-synched death-metal soundtrack, Brophy reveals just how skin deep our acceptance of style actually is.

To produce this first installment of Evaporated Music 2: At the Mouth of Metal, Brophy first locked up a click- track digitally to the existing pirated song and then erased it. Next, his new vocal parts are overlaid in synch with the pre-existing mouth movements of the band. According to the artist statement provided the next stage of the process involves working without looking at the pirated visuals in order to focus upon the new composition. In the spaces between the vocals, and working to the click-track, Brophy composes a new track, working in the style of contemporary Scandinavian and Eastern European death-metal (and yes we can confirm with any surprisingly friendly death-metalhedz exactly where the new centres of death-metal are), then adapts the mix to his signature quadraphonic space, “jettisoning drum elements widely across the space, and splaying shredded guitars and slabs of fuzz into front and rear spatial spectra”. [6]

Considering that Brophy has long rallied for the significance of the movie soundtrack versus the primacy of the image, it is interesting to note with both Evaporated Music 1+2, he has successfully added extra emphasis to his audio compositions by using only unaltered visual elements. A visual arts audience, by default, is therefore forced to actually listen in order to read the work. Despite any precursory dismissal by a visual arts audience of his po-mo styled appropriation, the visual simply becomes a platform, on which one can really take notice of the soundtrack. Any manipulation, authoring, or editing of the visual component would distract from the importance of the audio elements. (...)

(...)

The subject of ‘surface’ (especially its quotation and translocation) still inspires contested division within contemporary art debates and it is typically within these debates that artists such as Brophy find their most likely critics. One Artlife blogger, referring to Evaporated Music 2, was unable to “believe that anyone can be bothered with mix ‘n’ match appropriation... let alone be willing to commit the energy to even consider what it might mean.”8 Somehow, former oppositionalities such as theory/practice, or style/ substance are still apparent. Although critical theory is a useful tool with which to analyse the cultural and political conditions surrounding artistic practices, it is certainly not a precondition of contemporary art. Important ideas are also developed from film, music and drug cultures, science fiction and popular media. Ideas such as appropriation existed as conceptual strategies in the visual arts well before poststructuralist and psychoanalytical inspired critical theory had developed intellectual currency.

In addition, myriad popular political and ideological shifts that have occurred since the 1960s and 1970s, as indicated by the proliferation of psychedelic, sexual and image consciousness in media, advertising and rock music, have all contributed significantly to contemporary artistic production methodologies without necessarily being ‘informed’ by academic anti-formalist criticism. Both anti-formalist criticism and contemporary art are contemporaneous responses to shared cultural and historical conditions. Australian critic Chris McAuliffe sees both as initially developing from “a limited and eclectic anti- formalism”, which later “split into critical and commodified streams”.9 Daniel Edwards, writing for Realtime, compares Brophy’s Fluorescent to Mike Parr and Adam Geczy’s The Mass Psychology of Fascism: Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, Zip-a-dee-ay (both exhibited at the Art Gallery of NSW).

Fluorescent and The Mass Psychology of Fascism are two sides of the postmodern coin. Brophy’s work celebrates the notion of self as nothing but the endless recycling of symbols and styles already in circulation. In contrast, Geczy and Parr’s visceral installation highlights the fact that in such a media-saturated environment it has never been easier for ideologically driven politicians to dictate the words, images and symbols through which the contemporary subject makes meaning.10

It was typically within the identification of such a split between critical and commodified streams that critics such as Hal Foster had first defined their assault on the latter. For Foster, “commodified postmodernism” had become a “neoconservative” formation, “defined mostly in terms of style”.11 Two decades later this split is still apparent, albeit with a new swag-bag of rhetoric, often unwittingly and paradoxically contributing to contemporary art’s globalisation of anti-globalisation. Biennale has followed biennale of politically correct (re)politicised video installation art, with accompanying catalogue essays so sympathetic that they invariably forget to mention art at all (as if art’s political function can really be read so literally). Conversely, Brophy’s approach, perhaps to a certain extent simply an updated extension of that of Warhol or Koons, is to engage with the infinity of surface. For Brophy, depth of surface is epitomised in contemporary Japanese culture, particularly manga, which is of course a primary influence; “In Japan, surface is sublime. Reality is not what they’re interested in. To them, it’s only an image! The amount of energy that can be packed into surface in Japanese culture is mind boggling.”12 So, for better or worse, and despite the efforts of critics such as Foster, formations “attached to the more palatable notion of style”13 continue (hopefully at least self-reflexively) to be produced, exhibited and discussed, remembering of course that even the pretence of radical political disjuncture is of course itself ultimately reducible to style. For as observed by American critic Douglas Crimp in 1983, “If all aspects of the culture use this new operational mode, then the mode itself cannot articulate a specific reflection upon that culture.”14 Perhaps, only once the paradoxical limitations of political radicality within the institution are acknowledged, can the more persistent noise and poetry of subtle transgression continue.

Even the distinction once drawn between material and stylistic appropriation by Crimp cannot be neatly applied to Brophy’s oeuvre.15 Although appropriation was in the end “just another academic category—a thematic—through which the museum organises its objects”,16 for artists such as Brophy both the recycling of styles such as glam, metal, or manga, or the material reuse of video-clips or television shows are as much a given as the digital technologies now used to produce artworks. Ultimately, both the computer and its recycling capabilities represent simply a means of artistic production, not an exhibited or critically significant end in and of itself. From the appearance of sampling in seminal African-American hip-hop in Brooklyn during the late 1970s, to iconoclastic punk rock poster and record sleeve designs, to retroactive fashion designers such as Vivienne Westwood or Jean-Paul Gaultier, to the inversions and reiterations of sexual stereotypes offered by performers ranging from David Bowie to Madonna, retroactive variations in popular culture have generally been at least contemporaneous with comparable variations in the visual arts. Far from directly informing or pre-empting its endorsement in popular culture, academic postmodernism can be more accurately described as a contemporaneous response to shared cultural conditions. Despite the fact that many influential French thinkers explored their ideas using examples cited from popular culture, places and events, ‘serious’ art criticism has often been more concerned with establishing relationships between French theory and art history. At the same time, parallel formations within music, fashion and film have also relied heavily upon the specificities of their own histories. Perhaps it takes an artist like Brophy, someone who “encountered Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Andy Warhol and David Bowie at an impressionable age”17 to recognise and intersect those parallel sub-histories. Just as in the visual arts, styles in music and fashion are often self-reflexively generated within specific vocabularies and information channels related to specific prototypical forms and staged in mock opposition to dominant codes. Even with the addition of the internet, cable television, and interactive digital technologies, the pattern remains the same. Each cultural sub-group continues to navel-gaze at the specificities of its own histories, albeit in infinite globally connected detail. It is finally irrelevant whether we read Brophy within the specific rhetoric of contemporary art, music, new- media, performance, film or indeed whatever fashionable intersection of all or none of the above that we care to choose. It does not matter. His work represents a contemporaneous response to shared cultural conditions in a technologically and now ‘glocally’ infinite present.

Brophy’s hybrid and interdisciplinary practice is predicated on fluid movement between medium and context. Beyond simply recontextualising a rock video clip in a contemporary art space, Brophy consistently challenges the role of audio as merely an accompaniment to the primacy of the visual in both film and contemporary installation art. The fact that most audio-visual installations are exhibited in sonically inappropriate white cube gallery spaces with the sound turned right down in order to minimise noise within the range of neighbouring exhibits is in itself testament to the primacy of the visual. Using surround sound systems in darkened and at least partially dampened (using curtains) rooms is certainly a step toward levelling the playing field. Even with such measures in place, the sound of death metal reverberating through the floorboards proved too much for Artspace’s upstairs neighbours, with the volume subsequently significantly decreased after the opening night and for the duration of the exhibition. Metal up your arse!

Evaporated Music 1, 2 & 3

published in Art Forum Vol.56 No.2, New York © 2017

by Helen Hughes

"Evaporated Music" (at Neon Parc, Melbourne) presented all three installments of Melbournebased artist Philip Brophy's eponymous suite of videos, marking the first time these works have been shown together. The three chapters displayed in sequence in an immersive environment with a monitor opposing a couch, a rug, and five speakers — each address a different way in which music is represented on video. While the visuals of the appropriated clips are left completely intact, Brophy — since the late 1970s a committed deconstructionist of cultural texts — gives the accompanying audio a complete makeover. His process is meticulous, resulting in perfect synchronization between sound and the action onscreen. Of course, the new soundtrack estranges the familiar visual content of the videos — the basis of the work's humor. A dedicated analytic project underpins the trilogy, one that is continuous with Brophy's parallel career as an art, music, and film critic.

Evaporated Music 1 (2000-2004) targets pop videos from the late '80s and '90s, when the genre approached the production levels and heightened artifice of Hollywood cinema. It begins with Elton John' s song "Sacrifice" and its highly stylized, intensely dramatic narrative pivoting around a fractious relationship between a heterosexual couple and their small child. With the song's repetitive, ascending-to-nowhere melody removed, and its chorus of "cold, cold heart" and "sacrifice" now rasped out in a bodiless electronic voice, John appears to be summoning the dark lord rather than crooning relationship advice to the unhappy couple. Celine Dion's "It's All Coming Back to Me Now," Phil Collins's "Father to Son," and Billy Joel's "We Didn't Start the Fire" are then subjected to similar treatment.

Evaporated Music 2: At the Mouth of Metal (2006-2008) syncs visuals of cheesy bands performing on late-'80s and early-'90s family-friendly television shows to Brophy's own imitation of extreme metal music. His rescoring of a clip from Saved by the Bell, for instance, causes teenage heartthrob Zack to croak lyrics like "Woman — some tarmac whore!" to the enthusiastic high fives and hair flicks of bandmate Kelly. Both these sets of videos lampoon the moral panic that beset middle-class parents of the '80s in response to metal bands' use of backmasking to layer their songs with satanic messages that can only be heard when played in reverse. It is as if Brophy enacts a type of critical (or paranoid) listening that lets him hear through the music in its original form — as if his versions of the video clips merely amplify what is already latent in the sound.

Comprising footage of professional and amateur string quartets playing in venues ranging from large concert halls to wedding marquees, Evaporated Music 3: Classical Corpus Delicti (2015) sits at a conceptual tangent to the first two entries in the trilogy, taking aim at the conservatory and the concert hall instead of popular culture and its music. In these clips, Brophy simply silences the musicians' instruments. As if in a highly theatrical cover version of John Cage's 4'33" (1952), all that remains audible are the sounds of their breathing, the rustle of their suits, the jangle of the beads on their dresses, the taps of their shoes, and the echo of the room in which they play — all of which Brophy has reconstructed in an exaggerated manner. But rather than aiming to open listeners' ears and minds to a more holistic array of sounds, as Cage sought to do, Brophy uses silence as a weapon to denude classical music of its transcendent, celestial aspirations and to ground these performers in a base, human realm.

In 2005, Brophy wrote that despite purporting to be open to all sounds, Cage and his successors have been "alarmingly dismissive of the noise of postwar American mass culture." The "Evaporated Music" trilogy may be read as the artist's riposte to this Cagean milieu, with the audiovisual complexity of '80s and '90s video clips cited as evidence.