Citizen Kane

Citizen Kane

The sound of the look of a 'visual masterpiece'

published in Music & The Moving Image, Vol.1 No.3, University of Illinois Press, Champaign, 2008(Originally written in 1989)

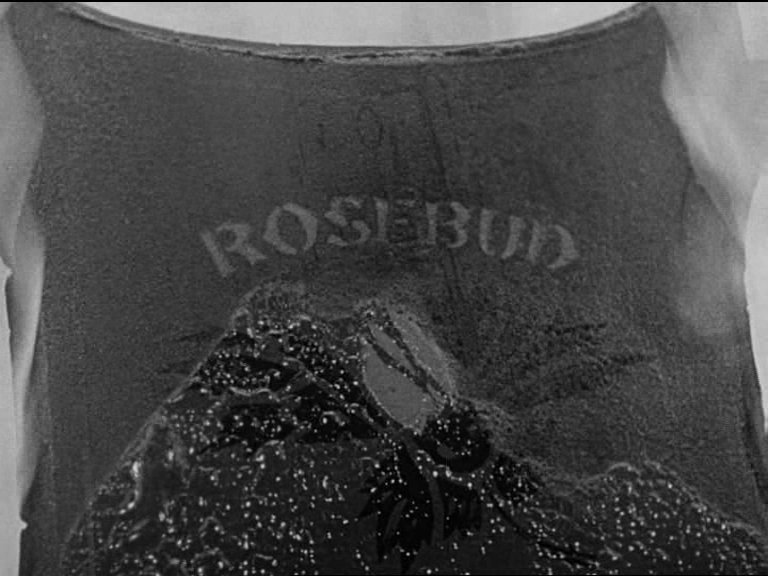

The precession of sound

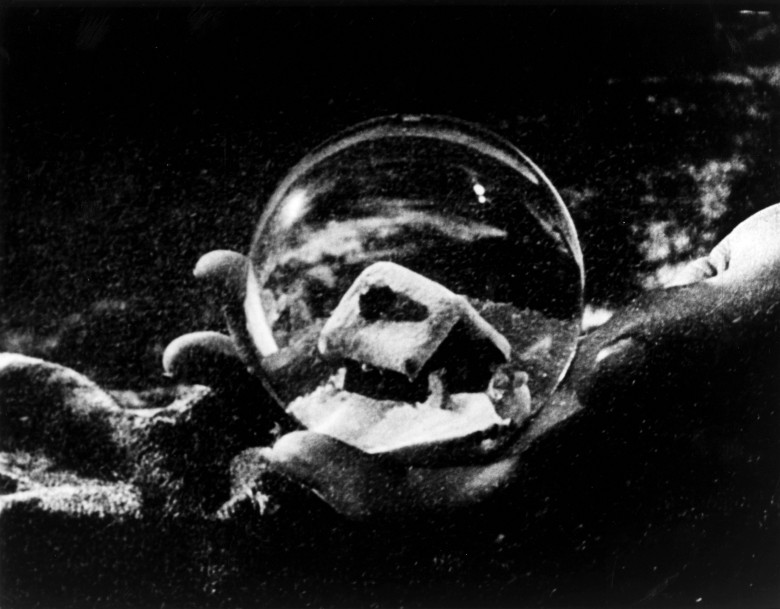

"Rosebud". CITIZEN KANE starts with a mystery that triggers its story. The enigmatic utterance of "Rosebud" is initially posited as an epicentre, a locus to the confounding behavioral nightmare that might have been Charles Foster Kane's life. As an unspoken logo on a burning sled, it is finally opened as a deep well of futility, a pathetic frustration of the search for meaning. All that a person may do and say might add up to naught; existence degree zero that disappears like the breath that carries the tragic neumonic of one's last word.

Yet if CITIZEN KANE is figuratively and literally about one's last word, it is also about the sound of that word and all the noise and silence that frames the sonic event; the preverberation and reverberation which holds that utterance centre stage in the film's narratological auditorium. Furthermore, CITIZEN KANE is not a priori a visual film. It is a sonic, acoustic, vocal text. Its beams of light, shafts of luminance, patterns of shadow are post partum visualizations of vocal presences, melodic flows, sonorous atmospheres. Just as Orson Welles' career in innovative radio drama (1935-9) prepares the way for his first film (1941), the soundtrack of CITIZEN KANE precedes its image. How frustrating that film history and cinema mythology has muffled the sound of CITIZEN KANE in the quest to amplify its overly stylized imagery. How perfect a film for studying the invisible yet powerful world of film sound.

True to the mystery which propels the story, there is much that is not said in CITIZEN KANE. Yet most of what isn't said is textually voiced through the human voice; through its utterances, its presence, its power, its musicality, its breath. It may be a tragic story about a Hearst-like figure and the morality of power plays on a political stage, but its formal construction, primary symbolism and temporal deployment are governed entirely by when, where, how and why someone uses their voice.

Highlighting voices by absenting faces

Picture the opening scene after the newsreel footage depicting Kane's meteoric rise to power and his plummet to disturbing isolation. Following that barrage of images and barking narration, the newsreel soundtrack drops in pitch as the projector is turned off. Both Kane's' flickering, scratchy life and the audio-visual mechanics of cinema are extinguished by this gesture. Darkness matches the silence that blankets the strange office space - more a mausoleum for inspecting the dead then a hive of inquiry expected of newspaper conference rooms. Picture that darkness, those silhouetted figures. Now try to remember a face. Any face. Scan it and you will not clearly see one face. Light has strategically been placed to prevent full facial illumination of any character in this scene. But this isn't a protracted exercise in compressing European expressionist and neo-Gothic aesthetics into the askew formalism of American noir. This scene is itself a trigger - to get you to listen to people's voices without seeing their faces. In short, this is radio drama introducing itself as the narratological form from which CITIZEN KANE is shaped. The irony of the scene is evident in that everyone is talking about the enigma of Kane, while we have no idea what any of these people look like: their visual mysteriousness reflects the dramatic mystery that is Kane.

Much can be made of this scene. Firstly the vocal performances are epicentral to the energy of the scene; the lighting is decorative staging in comparison, while the editing follows aural rhythms in favour of visual rhythm. Listen to the voices' timbre, their phrasing, their pitch modulation. They dart across the blackness of the room like melodic lines; the beauty of their sonority enhanced by their visual anonymity. These are voices that are a pleasure to listen to - a key ingredient in the attractiveness of radio drama and an aspect of screen presence often ignored in sound cinema.

Secondly, there is a thrilling sense of orchestration audible in the scene. The voices weave in and out from each other, sometimes picking up the rhythmic banter of the former, other times dominating the other to create a rhythmic and timbrel shift. The voices in this sense map an aural dogfight as the characters' are energized by each other, responding to each other's lines and having flashes of ideas which give rise to rapid fires of dialogue. This swirling dynamo of group vocal action lets the scene convey a sense of vitality that kick starts the investigative story for CITIZEN KANE.

Thirdly, each vocal performance carries variance in delivery and dynamic range. There is a genuine sense of the performers' shift from raw babble to contemplative whisper. Such contrasts in intensity colour the psychological state of the characters at these moments, giving us an insight - via their voice - to their capacity for change and the range of their emotional energy. This may sound a mute point, but without this attention to detail in vocal performance - not in terms of diction and enunciation but in verbalization and expression - an actor's performance can become flat and bland. The voice which speaks without inflection more than likely colours a character as being mono-dimensional: we get no sense of their potential range of emotional expressiveness. Particularly at the close of the scene, when the editor gets Thompson, the reporter (William Alland) to focus on the enigma of Kane, we get a clear sense of the editor's passion and the reporter's realization that this is a story which would be interesting to follow up. And all of this with no more than the scarce profiles of faces which we shall never see.

Aspects of characterization in vocal performance

The 'flair' of Orson Welles ultimately lies in his direction of his stock company as vocal beings; as instruments for an arrangement of aural, acoustic and musical thematics. The opening scene is brimful of sophistication in vocal performances which works as an overture for the vocal performances of the main cast - a sure sign that Welles' sense of continuity in staging and direction of actors was always controlled and determined. The reporter is a key vocal instrument in this way. As the 'us' in the film - always seeking answers to gain meaning from incidents he did not witness - his function is to ask in order to seek, to question in order to assess. His instrument is his voice, and the logic of the film has us experience his voice in this manner. He is the detective for this mystery, supplanting conventional voice-over narration with a presence within the aural diegesis of the action while remaining visually absent.

The reporter's voice has a deliberate blandness to it, signifying a matter-of-fact approach and the 'uncoloured' tone of his investigation. Most importantly, he provides a standardized vocal performance against which the more 'colourful' characters in the film are measured. His interview of the aged Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore) brings out her raspy tones where phlegm and alcohol lubricate her repressed anger; his quizzing of the shifty butler Raymond (Paul Stewart) solicits a deeply ironic utterance of "Rosebud" as if it were the spluttering sign of advanced senility; his attempts to ask basic questions of the stern librarian push her to hiss whispered directives which despite being low in volume silence him through the iron-clad insistence of her delivery.

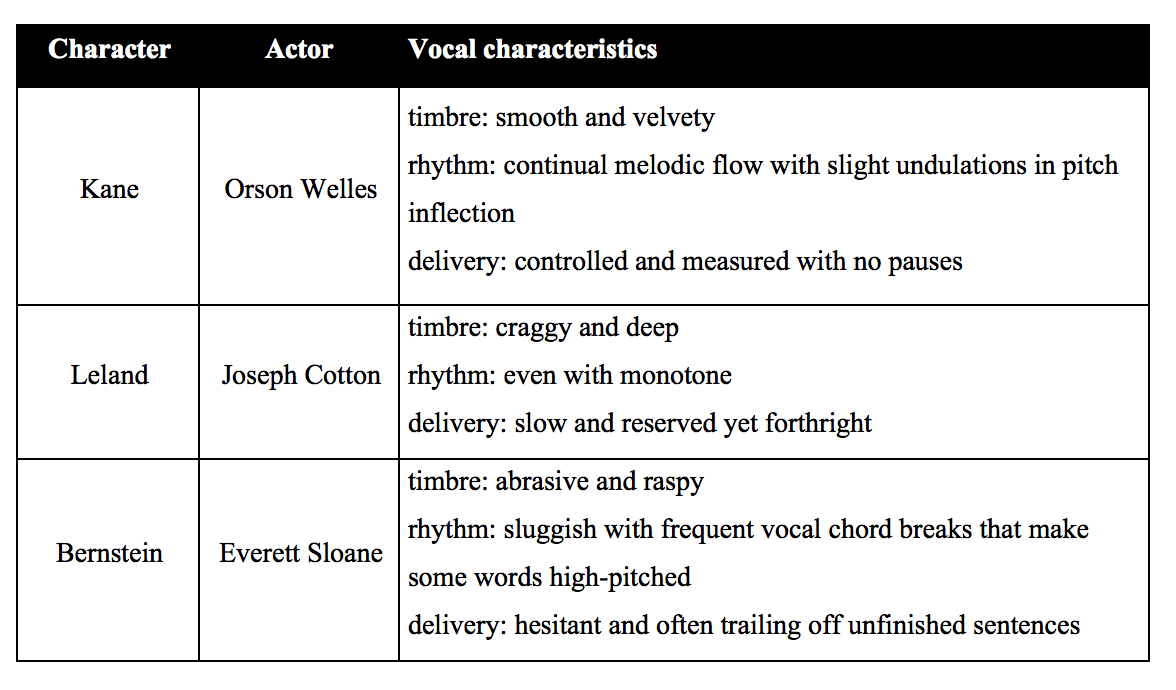

Let us observe an early scene predicated on bouncing voices off one another in a more complex manner. At the staff party for The Enquirer, vocal timbres are differentially circulated within an extremely noisy environment. The dynamic interactive crux of this scene is Jed Leland's (Joseph Cotton) observation of Kane: Kane puts on a song-and-dance (literally); Leland reflects on Kane & talks intimately with Mr. Bernstein (Everett Sloane); they intermittently sing along with Kane; Kane talks with them and the others across the raucous table while the music continues. The psychological perspective of the drama shifts from objective depiction of Kane to Leland's subjective impression of Kane, and is refracted by both Bernstein and Kane's view of Leland's reflective mode of discourse. While camera angles and editing are traditionally held as the primary means of organizing meaning and purpose in dramatic exchanges (and this sequence is quite in awe of Eisenteinian effects), the scene owes much to vocal interaction. This is especially so considering the technical contradiction the scene is based on: articulating, demonstrating and even celebrating vocal differences in characters by having them all talk across one another in a party scene where everyone is talking, yelling, singing. The cunning and oft-neglected means by which this scene works lie in two areas: vocal casting and voice mixing.

Firstly, let us consider the characters in terms of their vocals:

Clearly, these vocal characterizations and performances are dynamically contrasted against each other. More precisely, a character's identity is formally embedded in his voice. This is an important historical factor in American cinema which governs much vocalization and vocal casting between the cross-over from silent to sound cinema (c.1927-1933, when voices invaded the so-called 'silent screen') through to the cross-over from radio drama to television drama (c.1948-1954, when voices were seen as 'small screen' factors to be replaced by new 'hyper faces' for the widescreen). The point is that the character, identity and performance of many film actors across these two decades was as much tied to their voices as their faces. Welles' first foray into the cinema uses actors he had previously cast for his Mercury Theatre radio dramas - actors who would form the characters in CITIZEN KANE as aural identities who articulate their psychology, enunciate their presence, vocalize their drama.

Yet this issue of casting is but one half of the narrative effect peculiar to the scene in question and CITIZEN KANE in general. The second half lies in vocal mixing, for once you have clearly delineated vocal identities, you can then more deftly combine their lines of delivery. The Enquirer staff party scene contains many deceptive shifts in volume levels. Consider how the mix allows the contemplative mumbling of Leland ride over the chorus girls' nasal refrains to allow both us and Bernstein hear him. To perform such a manoeuvre, one would have to alternate foreground and background levels for both characters and the singing girls. Throw in Kane and assorted on-screen laughter and applause by the other guests seated at the long table, and you have a mix containing individual vocals which are layered by continually shifting volume levels. In this respect, Welles could be considered as much a conductor as a director. Just as the conductor determines rises and drops in energy level through dictating performance parameters, so does the soundtrack's mix control the interaction between the on-screen characters' performance energy. Welles does not simply employ overlapping dialogue: he consistently modulates the volume of every character's voice to further shape the dramatic material.

Transitions and transformations in vocal characterizations

A key feature in many vocal characterizations lies in the way that change within a character - through age or state of mind - is expressed through differences in vocal performance. The above scene of The Enquirer staff party is framed by Jed Leland's memory of the scene. He recites his story to the reporter in an aged gruff voice, often breaking into coughs, distracted asides and memory gaps, wheelchair-bound as he is in a home for the aged. While make-up conveys plot information - Leland is now old, was once young - his voice conveys character information: this rickety old man with a playfully devious edge was once a contemplative soul. Other characters have similar depth of transition conveyed through their voice framing a remembered story. Susan Oliver's tired and haggard tone frames what was once a spirited and fiery amateur soprano; Bernstein's weary, measured tone reveals in flashback what was once a lively-spirited disposition. Such transformations elaborate the depth of these characters across time, as age decreases action and increases contemplation, imbibing many of the flashbacks with a sad and elegiac quality by returning us to the voice of the present and the aged.

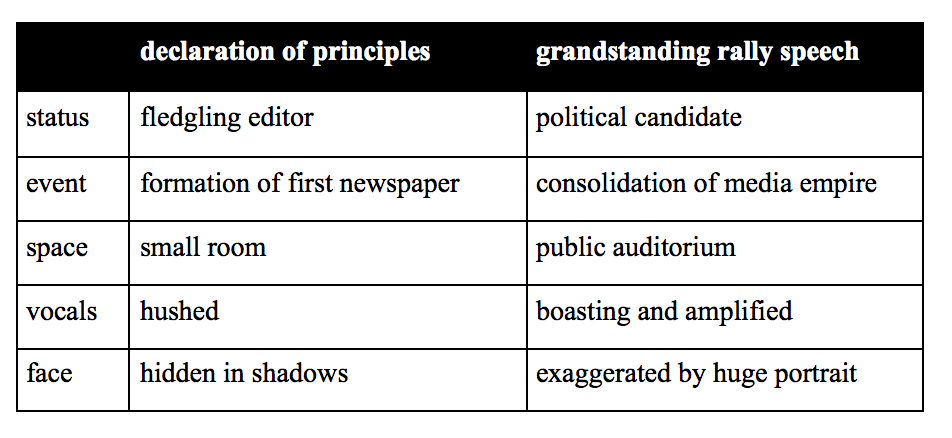

Kane himself is framed this way. Our first aural impression of him is via his last word - more breath of a dying lung than energy exerted through the vocal chords - and snatches of crackling newsreel footage, all of which give us an old man. We finally get to hear the youthful Kane's voice as he turns in his office chair to face Mr. Carter (Erskine Sanford). Kane eloquently, snidely and confidently returns each exasperated retort of Carter's in a virtuoso display of verbal volleys: this man could talk anyone into anything; his power is in his voice. Before too long, an image of Kane develops that wavers between passionate dedication to a cause and manic obsession with control. The more he exerts falsehood, the more he bluffs and the more commandeering his voice. But when he is truthful, he is quiet, withdrawn, modest. Compare two scenes: one where Kane reads his declaration of principles; the other where he delivers his grandstanding rally speech. Consider their oral, acoustic and thematic differences:

Let us outline the above schematic analysis. When Kane has completed his declaration of principles, he turns off the gas lamp as dawn light creeps through the window. He leans forward and is strategically placed so that his face is silhouetted, recalling the dark shapes of the opening scene's newsmen. As a newsman, Kane here symbolizes the noble and ethical aspirations of the press - those who erase themselves in the name of the truth, absenting their visage in the face of the plain facts they present. Furthermore, Kane almost whispers his written speech, suggesting that the truth is so fragile it cannot be declared aloud. Kane himself is similarly declaring his own truth, his heartfelt ideals as opposed to his careerist aspirations. This, too, is something he finds difficult to convey through his loud personality. As the film develops, Kane's corruption - signposted as the gradual deviation from his declared principles - is evident in his voice. The more low key and quiet Kane is, the more honest his words; the louder he is, the less honest his directives.

The sincere Kane ultimately becomes the political poseur. His voice will make the masses tremble. His mission is to amplify his voice through his media empire and thereby decimate the walls of corruption with the power and presence of his voice (consider the numerous newspaper names based on this ideal: The Bugle, The Clarion, The Call, etc.). Kane's power lies not only in what he says and proclaims, but in the volume of his voice, the spread of his oration, the extent to which he is heard across the nation (as represented by the animated sound waves emitting from capital cities across the USA in the opening's scene bio-reel). Ultimately, media power is located in the power of one's voice more than in one's face, and Kane the media baron is primarily concerned with being heard. In the auditorium, he holds many ears captive, but the impression garnered from this scene is one of a man that boasts. His words are proclaimed at an excessive level, thereby rendering them suspect. He holds court purely through volume, through generating an excess of vocal energy which distracts the listener from analyzing the words being delivered. The call-and-response device is a standard propaganda trick whereby the speaker gets an excess of crowd noise and applause to create a sound wave that implies that the speaker's voice is of a proportionate energy level. The auditorium, however, is also shown in long shot - not just visually but acoustically. As political rival Jim Geddes (Ray Collins) listens in the dark, we hear Kane's voice ring hollow, reverberation blurring his words and causing them to float without focus in the upper reaches of the hall.

In keeping with the tragedy of CITIZEN KANE's story, Kane's many dilemmas are situated by his not being heard. Characters disconnect from him by placing themselves out of earshot. Jim Geddes simply walks away as Kane screams empty and ignored boasts of power. Kane's wife Emily (Ruth Warrick) walks out because he does not listen to her, leaving him to face the reality that he cannot control people once they refuse to listen to his voice. In a harsh inversion of the auditorium scene, the aged Kane is left isolated in a Susan's bedroom. No expansive emptiness and exaggerated scale here: Kane is displaced by the human frailty and perspective of the room. It even contains numerous miniatures and figurines which emphasize his gargantuan nature. A period of silence follows - then an onslaught of aural destruction as Kane rampages through this microcosmic world like an enraged Godzilla. With a pained but fixed countenance, he hurtles through the domestic realm creating a cacophony of destruction. The onslaught of noise occupies - obliterates, even - the soundtrack, speaking the unspeakable, for Kane cannot admit defeat. He is tongue-tied and limbs-akimbo. Only when he runs out of physical energy does silence sweep over his aural desecration, creating a hole in which we hear the enigmatic "Rosebud". Spent, drained, silenced; here is the core tragic moment of CITIZEN KANE: the most personal comment he makes in his whole life falls on absent ears.

Determining relationships between spatial acoustics & mise-en-scene

If I am accurate in re-imagining CITIZEN KANE as the visualization of a radio drama, it is because there are many instances in the film where it is hard to picture the film's mise-en-scene having eventuated in any other way. Mise-en-scene - properly, the staging of drama - is a term inherited and borrowed from the theatre. Theatre, of course, is a priori audio-visual: it takes place within an auditorium, not 'upon a screen'. The notion of a director strategically carving up space and time can easily be postulated as an operational concept in theatre and the cinema - so long as one acknowledges the prime difference between a real-time aural continuum (theatre) and a deconstructed assemblage of aural layering (cinema). Simply, stage something in the theatre and sound will follow inevitably; stage something for cinema and you have to decide how you will either record or remake the sound that follows your action. CITIZEN KANE not only poses this base audio-visual problem: it interrogates and explores all the cinematic mechanisms which reinvent mise-en-scene as a deconstructed event.

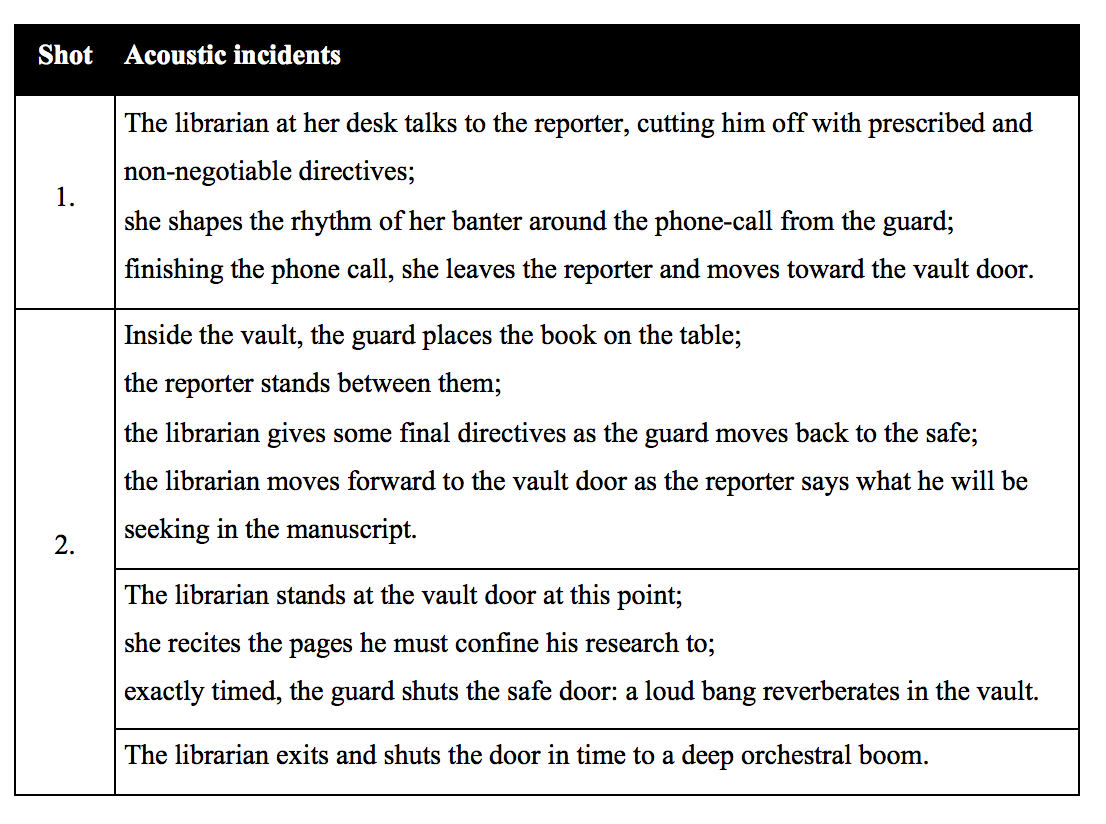

Specific shot sequences within two scenes demonstrate this well: the reporter requesting to see the transcripts of Mr. Thatcher from the librarian (told mostly via real-time/space passages), and the young Kane being orphaned out to Mr. Carter (told via the use of depth-of-field cinematography and screen mattes). The library scene is deceptively simple. Plot-wise, the first shot tells us that the reporter wants to see Mr. Carter's transcripts and that the librarian allows him into the vault under strict conditions of access. The camera shifts from mid-shot on the two of them to a slight track which dissolves into a shot of the large room, framing the reporter mid-field, a guard in the background and the librarian in foreground. Standard stuff. Now let us look at the acoustic placement of incidents within the space across those two shots:

What can be deduced from this? Firstly, all characters speak and move in a choreography conducted via the marking of sounds against silence, foreground against background. Secondly, the timing, duration and delivery of dialogue is matched to and/or has determined the scene's spatial mise-en-scene.

The production design is based around the placement of the foyer in relation to the inner sanctum, plus the empty openness of the marbled spaces. The art direction features a long vertical table plus a mid-height safe to place the guard in the background to accentuate the loud boom as he shuts the safe. The cinematography employs a slight forward track followed by fixed framing to define and document perspective through aspects of reverberation. From this networking of visual logic, one can nonetheless see that acoustic considerations have been acknowledged and exploited even. More so, much of the 'visual flair' of CITIZEN KANE gains strength and clarity from the sono-acoustic effects and properties which in many a film are ignored or unrealized. The 'look' of CITIZEN KANE is precisely the 'look of its sound', just as its sound design is the 'sound of its look': the film boasts and benefits from a rendering of the close harmony between its audio and visual tracks.

But while CITIZEN KANE tends to stylistically forward set pieces to demonstrate this audio-visual harmony, it is nonetheless a film governed by dramatic logic in the organization of sounds and images. The scene where the young Kane (Buddy Swan) is orphaned to Mr. Thatcher (George Coulouris) is most appropriate in this respect. Infamous for its use of depth-of-field cinematography (yet clearly featuring as much matte optical work), this scene reveals how densely the soundtrack is welded to the cinematography. Just as the library vault scene is revealed through the act of listening, so does this scene: a triangle based on who listens to who and whom is ignored forms its dramatic epicentre.

Within this triangle of listening, a key event creates the dramatic fulcrum to the triangle's pivot: Mr. Kane (?) absent-mindedly closes the window and Mrs. Kane (Agnes Moorehead) immediately responds to the momentary loss of the sound of young Kane's voice. In automatic maternal mode, Mrs. Kane cuts across the space and opens the window again. Precisely at this point, the camera cuts outside, from the dark claustrophobic space where the adults are squabbling to the wide, white playground of young Kane. The camera centres Mrs. Kane's face in close-up, communicating the anguish she suffers in sending her son away. Young Kane's voice continues its innocent whining while a light wind sound freezes her outward emotional expression: her eyes glaze over; her voice does not waver. This moment is an acoustic poem which binds the scene's dramatic core, concealing it within the flaunted staging of raked stages, up-tilted camera angles and deep focus cinematography. Listen and you will perceive the scene in its totality.

Verbally generated and aurally effected narrative devices

Even if one missed the audio-visual fusion of elements detailed thus far, it is hard to not be aware of the games played throughout the film's hyper-elliptical cross-cutting. These moments belie a background in theatre and radio, wherein the script is taken less as a fundamental manual and more as malleable material for a playful transformation from the written into the oral. Two editing techniques take their cue from this kind of playfulness: the first is to do with the grammar and meaning of verbal exchanges; the second is centred on using the presence or texture of a sound effect to exact spatio-temporal changes. Together, these categories encompass the range of verbally generated and aurally effected narrative devices which drive the rhythm of CITIZEN KANE's overtly formalist editing.

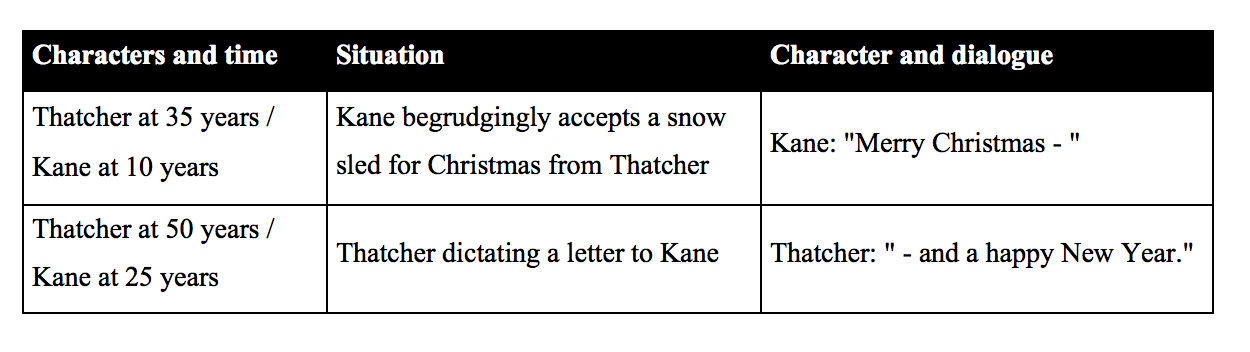

The first category is exemplified by the bulk of Mr. Thatcher's flashback via his memoirs. One must remember that this flashback is written not spoken: the reporter is reading from the deceased Thatcher's memoirs as opposed to other living characters who speak to him. Enforcing this, we are hurled into a realm of letters:

Around fifteen years disappears into that single cut: time and space are radically shifted while grammatical syntax is held solid. In reference to mention made previously about vocal performances, the cut is as much musical as it is grammatical, spatial and temporal. Listen to the pitch and phrasing that butts the conflicting tones against the other: Kane's insincere groan and Thatcher's authoritarian bark clash as much as their personalities. Their utterances have been conducted, arranged, composed to form a moment of musical contrast to carry the dialogue. This is the script being handled as 'malleable material': the speaking of dialogue is not treated as the neutralized breath of author-controlled characters, but as preformatted substance in the organization of cinematic effects. Thatcher becomes the major receptacle of this playfulness and malleability. His next scene is as much concrete poem recital as it is acting. Kane has purchased The Chronicle and is churning out sensationalist headlines. In a series of jump cuts, more people are reading the paper as the headlines become more lurid. Thatcher reads each headline aloud in disbelief until finally he is left speechless.

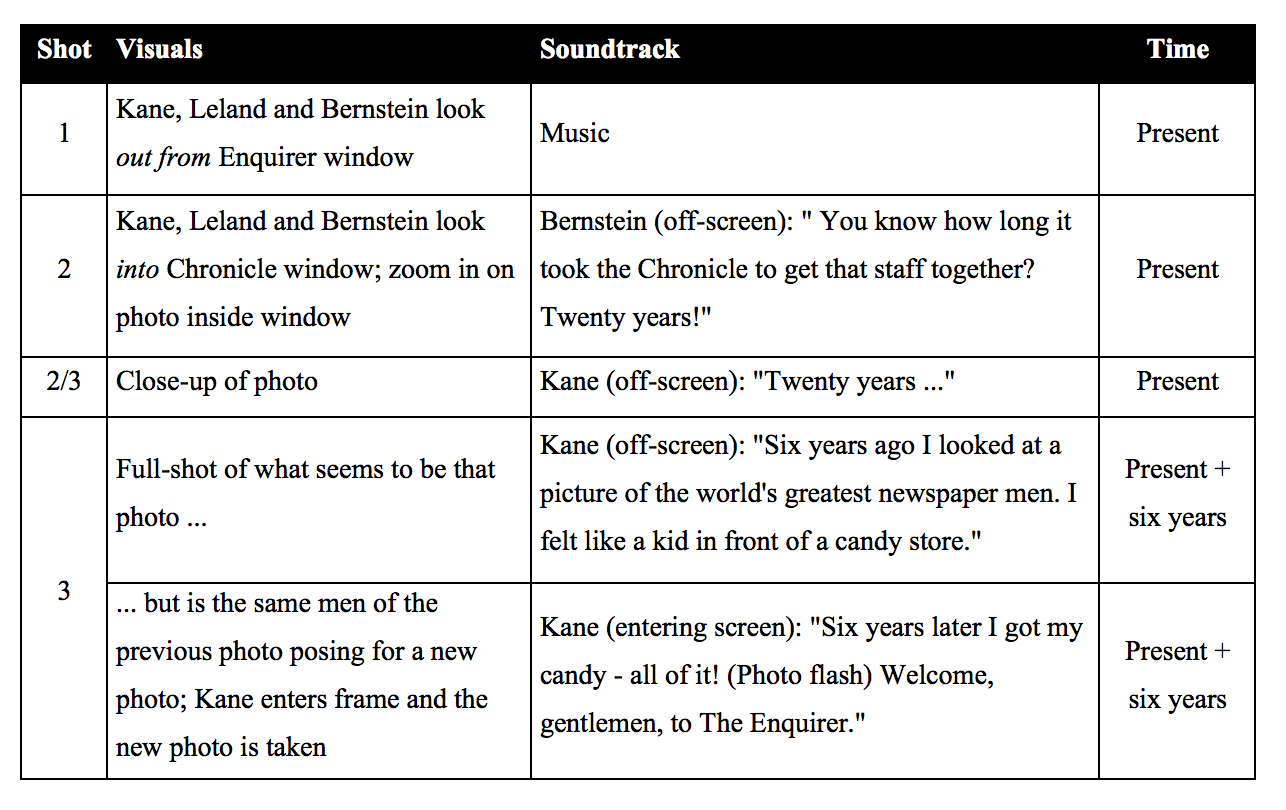

Within the flashback of Jed Leland, numerous ellipses unfold and surge forward as Leland details the fatalistic rise and fall of the maniacal Kane. Each of these scenes contains a dramatic epicentre which determines an outward constellation of narratological form. For example, the rise of Kane's business nous is synergistically described in terms of a deft and wily cinematic playfulness. As Kane stands with Leland and Bernstein in front of a photo of The Chronicle's staff, a narratological blur occurs between the visual shots and the soundtrack, siting the dramatic, grammatical and formal crux of the scene in the invisible dissolve from a still photo in one point in time to a recreation of that photo six years later:

A similar 'sleight of sound' occurs through the condensation of time in Leland's flashback to Kane's first marriage to Emily Norton. A series of breakfast table encounters between Kane & Emily are strung together, using the musical device of variations on a theme. As their marriage crumbles across each hyper-elliptical edit: (a) the music becomes sullen and solemn; (b) the pitch of their voices becomes lower and monotone; and (c) they each speak less, finally saying nothing and reading opposing newspapers. Precisely, the musical structure of this scene embodies the narrative's purpose. True to the highly formalist logic governing the narratological denouement of CITIZEN KANE, metaphor and symbol in these playful flashbacks of Leland are deeply encoded in the cinematic mechanisms of their suggestion.

Less overtly structuralist and more poetic and evocative are moments when sound effects perform as aurally generated narrative devices. Numerous fleeting details sparkle throughout the mix of CITIZEN KANE where the presence, texture and placement of a sound narratologically enhance the sound's base semantic content. One key instance - how the sound of a newsboy's voice becomes more than its 'content' - requires aural scrutiny. Kane and company have just taken over The Enquirer, much to the frustration of the newspaper's manager, Mr. Carter. After a bustling collapse of day into night, Mr. Carter leaves early the following morning, having been driven to stay back over night. He stands on the steps outside the tall building; a paper boy stands hawking the forthcoming day's paper. A tricky track-matte-dissolve then takes us to Jed Leland high up in the building looking with bemusement at Carter below. Across these two shots, the sound of the paper boy's voice becomes entirely reverberant.

Now, reverberation is essentially the microcosmic refraction of frequency data from a single sound event within a space so as to render the event diffused and to disfigure its original dynamic shape across time. In other words, as the paper boy's voice wafts up from the street to the top floors to be heard by Bernstein, the boy's voice becomes a blurred and illegible vocal texture. Reverberation is one of the many unique and scintillating aspects of sound which confound visually-derived ontological precepts: the boy's reverberant voice is clearly a voice, clearly his voice, yet has been emptied of its content (the words) so as to give us the aural phenomenological experience of a paradoxically specific 'voiceness'. To anyone trained in audio or musical fields, reverb is an everyday fact of life. But through a shift in the mix from a single legible voice to a reverberant textural 'voiceness', Welles manipulates an everyday aural effect - lasting no more than around 4 seconds of screen time - to generate dense narratological and symbolic meaning.

Firstly, Kane and company are on the top floor at the end of their day (morning) while Carter is at street level at what should be the start on his day. To him, the paper boy's voice clearly communicates how out-of-synch Carter now is: his nine-to-five sense of temporal order has been drastically unsettled. Judging by Bernstein's bemusement upstairs, the newspaper boy's voice signals the end of a normal round-the-clock day/night's work, where the news to be printed must be so up-to-date that it has to be composited in type just as the paper boys across the city open their mouths. Secondly, to Carter, that single boy's voice is an indication of Carter's myopia - the voice is perceived as an out-of-whack rooster's crow that irritates Carter's self-centred preoccupations; for Bernstein, the boy's diffused voice carries with it all the other newspaper boys' voices which collectively sound the power of distribution and the spread of the written word. Thirdly, the narrative realm of Carter down on the street where sound is 'actual' and unaffected signifies the mechanics of the newspaper - the logic and order of how it is materially composed, published and circulated. But in the airy space high above the street, the floating reverberant voice of the paper boy signifies Kane's editorial perspective - god-like, idealistic, utopian, omnipotent. And fourthly, the clear voice of the boy on the street for those who hear it there is simply a present-tense isolated incident, devoid of any further note; but for the idealistic aspiring editorial gathering upstairs, the diffused 'voiceness' caught outside the window is a multiplied and pluralistic mass of voices in both the present and the future - the potential for increased circulation and wider readership. Ironically, Kane hears only this 'voiceness' - this presence of the exploitable masses - yet does not understand a single word they say.

One more noteworthy example of densely compacted poetic significance pin-pointed by a single sound effect. After hearing Susan Oliver's debut operatic performance, Leland embarks on writing a bad review, but falls drunk at his typewriter. He awakens to the distant sound of typing and in his stupor thinks he is doing the typing. This gag then gives way to drama as the soft distant typewriter tapping is cut into by the harsh grate of a forceful carriage return. On a full screen in tactile close-up, the word "weak" is tattooed into the paper grain, seared with the intense anger of Kane typically driven to prove his own ethical point: he will not alter the truth of Leland's negative words no matter how much pain he brings upon himself. Yet it is only when we cut to the shot of Kane doing the typing do we garner the full dramatic weight bearing on him, as he has been visually and sonically introduced via a musique concrete collage of typewriter sounds. The clarity of the Kane's character here is the direct result of the soundtrack's incisiveness. And just as Kane and Emily's marriage deteriorated into a non-communicado face-off, the sound mix resides when Leland enters Kane's office to say "I didn't know we were talking". Kane continues typing, flagellating himself with typewriter keys that crack the paper as if it were his own flesh.

The power of the voice that sings

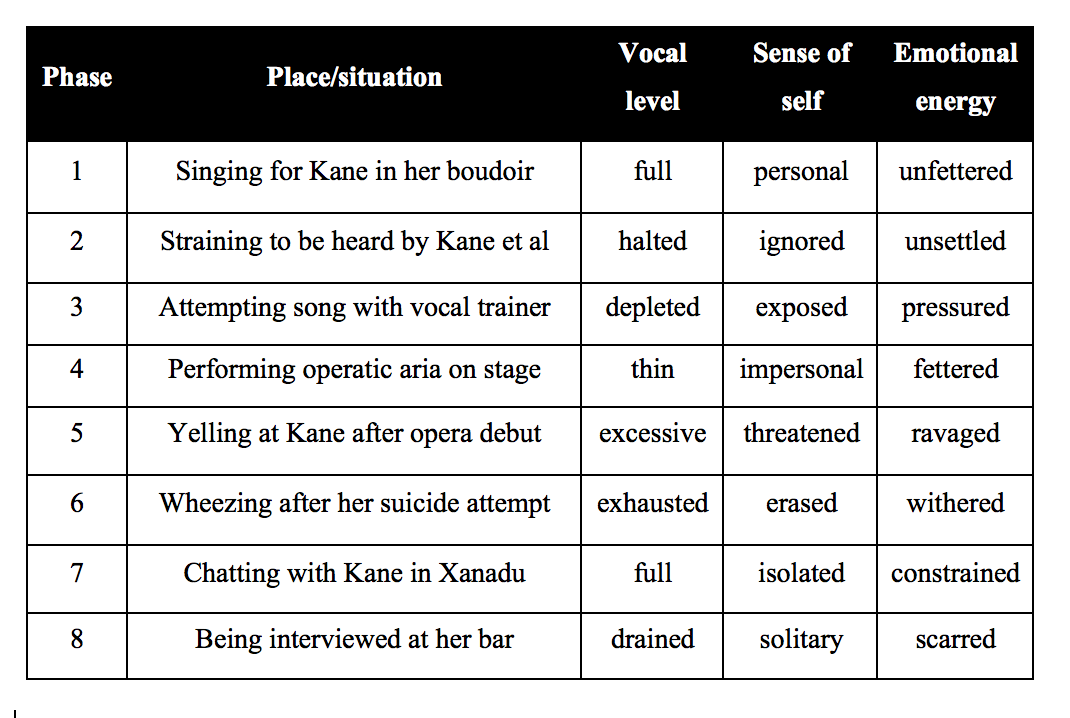

The ill-fated singing career of Susan Oliver has been referenced a few times already. Yet it is only now - after exposing the myriad of unspoken and invisible mechanisms which dance and sail across CITIZEN KANE's soundtrack - can we fully tackle the film's subtextual silent scream: the possession of woman's voice by man.

Kane's first impression of Susan is of her voice: he stands splattered with mud by a passing car while she giggles uncontrollably (off-screen) at his misfortune. He berates her and hears her speak through a tensed jaw due to her toothache. Moving to her boudoir, she sings for him accompanying herself at the piano. In her quiet domestic space, her voice charms Kane, soothing his fixation on worldly issues with her disarming naivete and quaint personality. As the soundtrack carries her singing, a visual dissolve indicates a passage of time across which Kane has been regularly visiting her for solace and comfort unseen by the outside world. This is the first phase of Susan's voice: full, personal, unfettered. Unfortunately for Susan, Kane perceives her fragrant voice in this personal space as an essence he must possess. Ignorantly and insensitively enthralled by the effect she has upon him, he will soon be intaking her voice like a drug.

But before that occurs, Susan is caught in a triangle - not the sordid 'love triangle' between her, Kane and Emily, but as a casualty of the power struggle between Jim Geddes, Kane and Emily. The drama unfolds in Susan's private chamber - a total invasion of her personal space. In this very room where Kane hung off every note she sang, he now shouts through her at Emily and Geddes. She pathetically struggles to make herself heard; everyone simply talks over her as if she was not there, as if she were a deaf mute. This is the second phase of Susan's voice: halted, ignored, unsettled. Traumatized by the drain of his power through losing his wife and his fight with Jim Geddes, Kane resorts to abusing the high originally granted him by Susan's voice. Her voice is no longer a direct source of pleasure - it is an escape from dealing with his disempowerment and a means by which he can cover it up. If he could not control Emily and Jim Geddes, he will control Susan - through opera.

Kane operates Susan's voice like a stilted aural marionette controlled directly by his vocal chords: he utters commands - she vocally contorts. He even employs a vocal trainer to further codify Susan's identity into a retainer of his control. As Susan undergoes a training session (singing the same song she sang so comfortably in private for Kane), a frightening struggle for power unfolds. The song - the fundamental harmonic text inscribed as law on the musical staves - acts as the authorial product they aim to create. Susan's voice struggles to hit the right notes; the piano sounds the precise notes she must match; and the vocal trainer sings directives on top of the same melody. All three voices are at the tyranny of the inscribed melody; all three voices suffer and are tormented by their inability to fuse and melt into the idealized version of the text's musical materialization. To Susan, the vocal trainer and piano player - and us as witness to this torture - the imperfection of her voice is evident. In steps Kane; he gets them to repeat the song. Uncannily, the very note Susan could not hit, she now hits. But this is because Kane is more terrifying then the inscribed text of the melody. He truly does have the power to pull Susan's vocal chords - not for her betterment and development, but for his own prowess and exhibitionism. Her singing has now gone from being 'truthfully imperfect' to 'falsely adequate'. Everyone in that room knows that Susan cannot perform opera, but their silence at the end of her second recital here is read by Kane as their approval of her specious skill. He smiles and remarks "I knew you would see it my way." This is the third phase of Susan's voice: depleted, exposed, pressured. A bird in a gilded cage.

The gilded cage eventually gives way to the grotesque opera house Kane builds for Susan. Just as he is driven to amplify his voice to monstrous proportions, he drives Susan to do so with her voice. Backstage, chaos and cacophony reign: the mechanics of opera spin around her, centring her as a pressure core which must bear all the fury of presentation which marks high opera as excessive and terrifying. In this sense, opera can be viewed as the hysteria of production where everything 'screams' - sets, costumes, lighting and orchestra. This creates a storm within which the frail human (archetypically a woman on the verge of becoming extinguished) is set, staged and framed as an icon of humanity terrorized by the deus ex machina of the production. Under this logic, Susan's plaintive tones and working class whine are hideously transformed into piercing squalls and an affected pomposity which cannot hide her inability to generate a prescribed operatic effect. The curtain lifts to expose her shortcomings to the world; her strained voice trails forth, floating upward to the scenic riggers - the very kind of people with whom Kane is so intent on bonding. They silently indicate that her singing stinks. This is the fourth phase of Susan's voice: thin, impersonal, fettered. Drained of her own identity, she is now visually and aurally a representation of the monstrosity of Kane's self.

This opera scene is later presented from the audience's point-of-view. We are now sited in the realm of those who can perceive what we know is a flawed and failed attempt to elevate Susan's voice to the level of a diva. A cross-section of the audience indicates she has little power to hold their attention as she did with Kane in her boudoir. Kane pathetically presumes that while she captivated him in a private situation, he can hold the public captive to perceive her in the same way. Maniacal to the nth degree, Kane not only ingenuously applauds Susan's weak performance, he also tries to control the audience's response by creating a wave of applause. Their clapping dwindles quickly, leaving Kane alone, desperately trying to simulate the noise of a whole auditorium. Their silence equals his drain of power, and no matter how 'big' he is, he cannot by himself be a voluminous mass - just as he will ultimately fail to control the masses. Applause simply cannot be falsely generated: it is the result of an organic real-time/space dynamic whereby each individual's reservoir of hand claps adds to the communal pool of group praise, representing a correlative level of appreciation through the volume and duration of roaring white noise. Kane's trauma lies in his inability to acknowledge this harsh reality. He may engineer waves of call-and-response approval at a political rally, but in the realm of art, instantaneous appreciation is controlled by the effectiveness of the art's presentation and its manipulation of an audience at that point in time.

The morning after brings an enraged Susan, humiliated and hysterical. Kane frowns at her disgustingly shrill caterwauls - but she is simply releasing the negative pressure he placed upon her. Her natural voice is soft and frail; she was forced to try and make it resonant and focused; it now has become stretched and abused. This is the fifth phase of Susan's voice: excessive, threatened, ravaged. When she protests doing any further performances, Kane's ominous shadow covers half her face. This is the terror of Kane: the true and monstrous status of his bulk. He is a deep shadow; a voice bellowing from the negative realm of the off-screen. He reduces Susan to a wide-eyed sliver of pale flesh, quivering in his dark and thundering presence. Interestingly, this figure has occurred once before - his shadow seductively swallows her into his alluring presence when they first meet in the boudoir - and will occur once more - when he insists she remain trapped in the echoic and alienating expansiveness of the Xanadu mansion. All three are key dramatic points which reveal the core dynamic of their relationship. If ever there has been an apt cinematic synonym for an overbearing masculine power intimidating a feminine presence, this interplay between loud, massive darkness and silent, shrinking light is it.

After Kane puts Susan in his place the morning after her debut performance, a nightmarish montage details Susan's whirlwind tour across America. This montage is effectively an impressionistic audio-visual poem replaying what it feels like to be the central pressure core surrounded by the whirling mechanics of an opera production. It swirls and spins until the core inevitably cracks, and timed to the light bulb being extinguished the screen blackens and the sound effect of her voice is mechanically left to wind down to zero-speed on a turntable. Once again, this isn't a showy self-reflexive gesture: everything potentially dies at this moment - the machinery of the opera (no longer with its propped-up diva); the power of Kane (no longer with his glittering bird); and Susan (no longer with the energy to live). It is befitting that the film itself winds down to a halt. Following this black hole a most remarkable and haunting moment occurs in the soundtrack (which unfortunately is difficult to hear on many prints of the film). The sound of Susan's slow measured wheezing carries over the vague silhouette of her prostrate figure. This is a being on the verge of death, experiencing her last phenomenological moment: the sound of her final breath. Kane will know this moment too: he will use it to recall the only moment of true happiness in his whole life, "Rosebud". But for Susan, there is no room for a happy memory; she has attempted suicide. This is the sixth phase of her voice: exhausted, erased, withered.

The scene continues. Kane talks with her after she has been treated by the doctor. As he sits by her bedside, the extremely soft sound of the aria that tortured Susan plays, entirely reverberated and diffused. This moment (once again hard to hear in some film prints due to its low level) takes us into the under-explored realm of psycho-acoustics in film sound design. This distant and diminished orchestral whine simulates the effect of, say, the ringing one feels in one's ears after attending a loud concert - the kind of sonic after-effect that can prevent one from sleeping well that night. Specifically, this is the sound in Susan's head: the music with which she has been bombarded and which poured out of her being night after night has turned her inside-out, leaving her shell-shocked and aurally battered. On top of this subtle yet torturous ringing she pleads with Kane to relinquish her from his murderous contract. He consents - and right on cue, the ringing stops. Her operatic career instantly fades into the past.

But Kane's possession of Susan does not stop there. He entombs her with himself like Egyptian royalty in the mausoleum that is Xanadu. Here both Kane and Susan's vocals are overpowered by the acoustics of their cavernous domicile. While the marriage between Kane and Emily broke down through lack of dialogue, Kane and Susan remain connected by illegibility: they each must incessantly repeat their speech as their words become dissolved by the intense reverberation that occurs between them. Their physical estrangement matches their aural separation which further matches their personal divergence. This is the seventh phase of Susan's vocals: full again - yet isolated and constrained. She is a bird no longer singing and left alone in a gaudy aviary. The space 'sounds' big, open and inviting - but it only serves to dwarf its residents, restrict their movement and silence their interactivity. For in the architectural utopia of Xanadu, Kane's unbalanced and exaggerated sense of scale blares from every crevice of its interior design. As in life, he is either too big or too small in the mansion's endless chambers; too loud or too quiet in its unfolding acoustic environs.

And so we come to the end of Susan's vocal trajectory. We have charted the life of vocal chords, her diminishing sense of self and the gradual seeping of her emotional energy thus:

Her eighth and final phase finds her drained, solitary, scarred. She sits craggy-voiced and weary-faced, as exhausted from her life as she is by speaking to the reporter of her past. Interestingly, seven of the above-detailed vocal phases are revealed only by Susan, indicating that Kane would have been largely oblivious to the trauma she suffered under him. Just as we can uncover the complex audio-visual mechanisms which drive CITIZEN KANE's formal construction by listening to it, so too can we fully perceive the psychotic dynamics of his psyche by listening to the effect it has on the voice of Susan Oliver. Susan is the sonic key, the aural lock and the vocal gateway to the pressure that builds up on Kane for him to explode, expire and enunciate "Rosebud". She becomes the ignored and unlistened-to pawn in the torrid love triangle which ends Kane's political career; she becomes the bird in the gilded cage Kane is bent on exhibiting to the world; she becomes the whisper of death which Kane saves and then encases in Xanadu; and finally she becomes the absent voice who no longer listens to him. She walks out and like a vanishing keystone causes Kane's world to shatter and shrivel, crackling into the sound of peeling paint as "Rosebud" disappears like the last echo of his voice.

Cited soundtrack incidents in chronological order

1. Alone inside Xanadu, Kane utters "Rosebud" then drops the snowball. A nurse draws a sheet over his body.

2. News On The March obituary of Kane is watched by newspaper men. A reporter is assigned to investigate the life of Kane.

3. Reporter interviews Susan Alexander at her night club but gets no information.

4. Reporter consults the archives of Walter Thatcher. Flash back to:

a. Thatcher acquiring Kane as a child from his parents. Mr. Kane senior protests; Mrs. Kane is adamant & young Kane is handed over to Thatcher.

b. Thatcher gives young Kane new sled.

c. Series of correspondences between Thatcher & Kane concerning the purchase & running of The Enquirer.

d. Confrontation between Thatcher & Kane at the Enquirer office.

e. Kane, Thatcher & Bernstein signing the dissolution of The Enquirer. End of flash back.

5. Reporter leaves the archives of Walter Thatcher.

6. Reporter interviews Bernstein in his office. Flash back to:

a. Kane taking over The Enquirer from Mr. Carter; shifts into the office with Leland & Bernstein.

b. Kane's declaration of principles as the first issue goes to press.

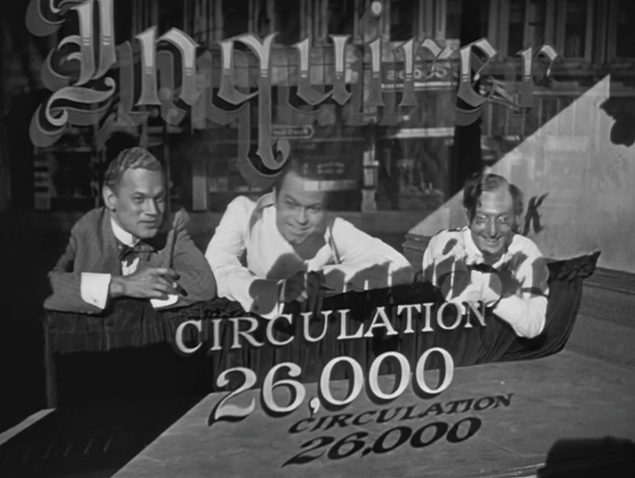

c. Kane, Bernstein & Leland observing the rise of The Enquirer's circulation of 26,000.

d. Kane notes The Chronicle's circulation of 459,000.

e. Kane welcomes the head-hunted Chronicle staff to The Enquirer at a fancy party.

f. Kane arrives back at The Enquirer from overseas with his new bride. End of flash back.

7. Reporter finishes with Bernstein.

8. Reporter interviews Leland at a home for the elderly. Flash back to:

a. Series of exchanges between Kane and Emily Norton charting the breakdown of their marriage. End of flash back.

9. Reporter continues interviewing Leland.

a. Susan Alexander & Kane meet; she takes him back to her place where they become attracted to each other; Susan plays piano for Kane regularly.

b. Leland drums up street support for Kane's governor campaign .

c. Kane delivers rousing speech at his convention rally; Kane watched by Emily and son; Kane also watched by Jim Geddes.

d. Emily forces Kane to take her to Susan's flat; there they meet Jim Geddes; argument ensues over Geddes' threat to expose Kane's affair with Susan; Kane decides to stay with Susan, leave Emily & continue to fight Geddes.

e. Bernstein supervises The Enquirer's first paper after Kane's loss at the governor election.

f. Leland is despondent over Kane's loss; confronts Kane over Kane's stubbornness.

g. Kane marries Susan.

h. Kane builds opera house for Susan; first performance bombs; a drunk Leland writes his negative review - Kane finishes it as Leland would have written it. End of flash back.

10. Reporter finishes interviewing Leland.

11. Reporter returns to interview Susan Alexander at her night club.

a. Susan is trained by vocal coach; Kane intervenes to make sure the coach does not give up.

b. Repeat of Susan's opening night performance; at close, Kane attempts to instigate mass applause but fails.

c. The next day, Kane & Susan argue; Leland returns by mail Kane's original declaration of principles; Kane intimidates Susan into continuing her opera career.

d. Montage of Susan's numerous performances.

e. Susan attempts suicide with sleeping pills; Kane watches over her after doctor leaves; Kane relinquishes Susan from performing.

f. Kane & Susan entombed within Xanadu - he is brooding & solitary; she is bored & frustrated.

g. An elaborate beach party is held; Kane & Susan fight - he hits her.

h. Back at Xanadu, Susan leaves Kane. End of flash back.

12. Reporter finishes interviewing Susan.

13. Reporter interviews butler at Xanadu . Flash back to:

a. Butler observes walk-out by Susan, then Kane demolishing her room; Kane clutches snowball & utters "Rosebud" then walks down mirrored hallway. End of flash back.

14. Reporter finishes interviewing butler; reporter talks with other reporters as Kane's possessions are being stored or disposed of.

15. A worker picks up the snow sled and throws it into the fire - the word "Rosebud" burns in the flames.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © RKO Pictures.