If You Read This You're A Dickhead - or - You've Got To Be Fuckin' Kidding

If You Read This You're A Dickhead - or - You've Got To Be Fuckin' Kidding

Infectious Humour, Affected Art & Referential Effect

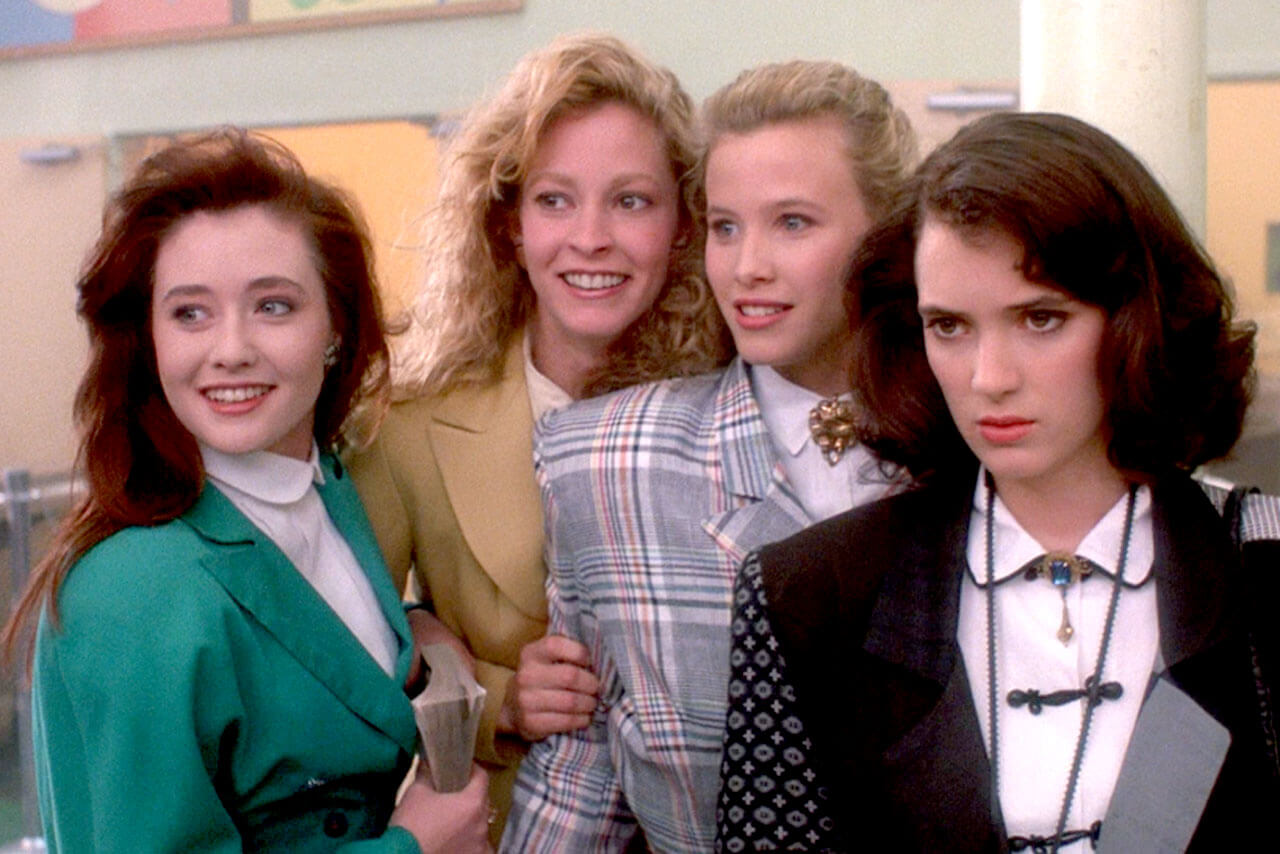

published in Wit's End, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 1993In a scene from the film Heathers (1989), one of the young rich bitches - all of whom call each other Heather - rips open her locker door. The scene in question is brief, a few lines of dialogue with the other Heather are exchanged in a crowded, middle class high school corridor. The mise en scene is set up to frame a passing parade of schoolkids, each belonging to one subculture or another, and to focus Heather against the inside of the locker door, festooned with scraps that make up her 'identity'. A flash of red surreptitiously catches the eye: a small red postcard with white letters in italicised Helvetica Extra Bold proclaiming I Shop Therefore I Am. Heather slams Shut the locker as an edit takes LIS to the next scene: BANG/CUT! Approximately 15 seconds of screen time in a film lasting around 100 minutes. Let's Start with that 0.25% of Heathers.

An audience hip-o-meter, would indicate that most people would find humour in the postcard for two distinct reasons: (1) they recognise the droll reference to Descartes' famous quote "I think therefore I am"; or (11) they've encountered variations on that gag throughout a fair portion of their lives, in either magazines, sitcom asides or witty editorial headlines (all of which have made numerous puns on the Descartes' quote). A smaller percentage would recognise the postcard as object, and identify the author of the gag as Barbara Kruger, the postcard being derived from one of her works from 1987. This is where things get complicated. Is the character of this particular Heather hip because (i) she is hip to (i.e. intellectually versed in), digs at Descartes ; or (ii) she is hip to (i.e. socially informed of), the anonymous spread of popular humour; or (iii) she is hip to the specific humour of Barbara Kruger (i.e. knowledgeable of what that humour implies in the context of contemporary, theory laden postmodern art)? If this question is absurdly rhetorical, does it consequently mean that the character of this Heather is vague, undefined and meaningless? Or is this particular scene totally insignificant?

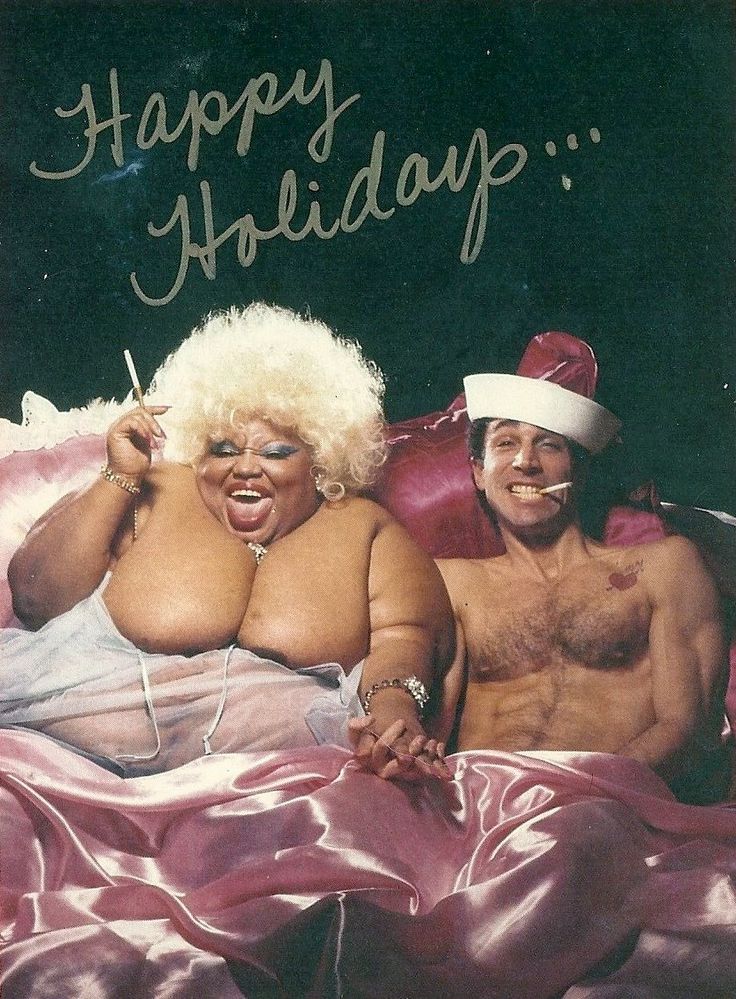

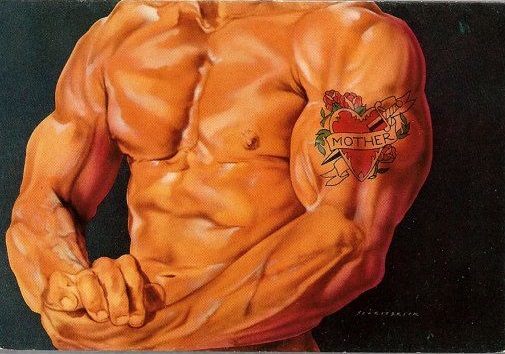

The old production of meaning template can actually be of some help here. Look at the credits at the end of the movie. In amongst the over 300 names listed, there will be some attached to categories such as production design, art direction and/or set decoration. One of them was employed to figure out what to stick on the inside door of Heather's locker, and given money to purchase those items. That someone also had to posit a script relevant reason for selecting those items, and their choice would have been approved by someone else, anyone from the head of art direction to the director, Michael Lehmann. Acknowledging this, we can replay our series of questions concerning the audience's level of cultural recognition to the person(s) responsible for selecting the Barbara Kruger postcard. Did they simply walk into a store like Heaven and spy the card amongst other 'cute' postcards, like those depicting John Waters' gargantuan screen queen Jean Hill, Japanese dressed up cats, or Paper Moon airbrush illustration of muscle men's sweaty buttocks, and think: "Hey, that'll do great for Heather's bitchy shopping mall character"? Or did they flash: "Hey, I'll stick in one of Kruger's postcards as a little in joke"? We'll probably never know unless someone from the production mentions it in passing in a published interview.

The Descartes/Kruger reference doesn't so much refer us to a textual location (this person who said that at one point in the history of discourse), but rather refers to a labyrinth of hollowed out cultural references, each and every one being a seismic site of previous usage. What we are confronted with in this excavation of language is a score of echoed voices, each repeating a phrase along the lines of "I think therefore I am", but not one declaring itself as the originating voice, or laying claim to authorial grain. If we were ever to navigate these labyrinths to discover Descartes down there somewhere, we wouldn't be able to hear his voice - his right to authorial power - due to the deafening din of those other voices and their vocal impersonations, impressions and characterisations. There is a simple metaphor for this: noise. An overload of communication due to multiple, simultaneous transmissions, which are beyond the directional capability of a receiver to distinguish or locate sources of utterance and emission. An equally succinct denotation is 'Popular Culture': the disembodied chorus of the amorphous masses. Far from being subjected to a communication breakdown or signal cancellation, those masses are the subject of references like the scene from Heathers. True to their name, the masses are as amorphous, yet material, as the gag in question is anonymous, yet multiple.

Such a minor incident in a film has allowed us to pinpoint certain crucial mechanisms of cultural referencing (which for the moment we can qualify as 'cinematic effect'), and to fix on the peculiar dynamic of quotation, which throughout the eighties has effected everything from magazine layouts, to stand up comics, to childrens' toys, to pop songs, to (at the end of the line), contemporary art. It appears that all have undergone condensation and displacement in the name of social commentary, rendering many poetic, structural and political interpretations of then meaning obsolete. Negative views of this demise of cultural and artistic discourse abound as cannibalistic, parasitic, or simply banal. Born from the frenetic pace of referencing, their allegedly amoral and ambiguous effects arc also experienced as being out of synchronisation with the measured construction Of literary signification, ie. the steady deployment of the message, the moral, the viewpoint, the concern, and the subtext. Such negative views are supported by architecturally derived notions of structure, meaning and signification, where things are built and handled like material according to a master formalist plan. Hence the collapse of meaning, the implosion of culture. the deconstruction of the text and so on.

But quite aside from the boundaries drawn between modernists and postmodernists is a different field of inquiry, where one can readily acknowledge that those cavernous paths made by incessant referencing and quotation eventually construct an anti matter version of the classical strictures of structure. Here the passages of negative space have become the very material from which a new construction can be engineered, and structure becomes something composed of, and defined by, an immaterial network. As hollow as the practice of quotation can be, it does not precipitate that erosion of its sources, but rather allows references to flow through semantic, symbolic, and semiotic tunnels, without halting or blocking them in the name of meaning.

As an audio-vistiual textual apparatus, cinema foregrounds a dynamic which allows references to flow on-the-run, and to alter them so as to facilitate its narrative tunnelling. Throughout the eighties (and especially in its address of the oppressive social realism of seventies cinema), movies developed mechanisms which foregrounded play, often throwing audiences into a labyrinth only to instantly recoup them. This is cinema which openly terrorises more than it placates, desensitises or inoculates. Certain directors made their reputation here, by relegating what were once structural conventions (plot, character, motivation, climax, resolution. etc.) to background staging and detailing. openly exhibiting narrative conventions and codes of realism as theatrical facades. Their movies invert the classical form/content and foreground/background relationships between mise en scene and narrative, subsuming everything into all expanded and destructured audio visual field of signification and effect; communicating through overload.

A good example is Joe Dante. He started editing trailers for Roger Corman's New World company, and eventually went on to make movies for their ribs and digs at anything you could think of. The Howling (1981), Gremlins (1984), Explorers (1986), and Inner Space (1987), lampoon culture and its artefacts with alarming precision, complexity. and speed. So much so, that their strata of referencing operates at a textual hyperspeed removed from both the rhythm of plot, and the flow of narrative (hence the afore mentioned effect of a reference being out of synchronisation with the literary text). Virtually every frame in Dante's scenes are brimful of colloquial and immediate references: TVs playing in the background, cars passing drive in screens, radios playing songs, posters on bedroom walls, badges and TV shirts on characters, snatched lines of dialogue delivered by characters whose names are puns on famous figures and so on, all creating a sensurround generated by mass culture's communication to its media self. The social fabric in Dante's films is threaded by intersecting airwaves: a material version of the immateriality of the negative space created by contemporary cultural referencing. On par with Dante's hyperventilating hilarity are John Hughes's teen comedies, particularly 16 Candles (1984), Weird Science (1985) and Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986), which operate along similar lines of transmission. Perhaps even more radical is the networking between Sam Raimi and Joel and Ethan Coen whose films Evil Dead (1982), Blood Simple (1985), Crimewave (1985), Raising Arizona (1987), and Evil Dead II (1987), collectively attain the mode of address, tone of delivery, and pace of presentation endemic to this type of contemporary cinema.

Heathers - salaciously marketed as "The Breakfast Club in Hell" - is not a particularly good example of this facet of eighties cinema (it is more an example of how carefully one can aim for a Cult audience), but it shares the reckless approach of Dante, Hughes, Raimi and the Coens, and does have its moments. The locker door scene with the Kruger gag is one of them because it initiates a crucial play with the audience. The hip player in this game is one who can spot the most immediate reference before it becomes lost in the secondary network of signs which immediately opens up. Recognising Kruger is then hipper than recognising Descartes. Perhaps this is one aspect of what is meant by the death of history - knowing the present or presence of an utterance in place of its past or passage. However, history is far from dead because its corridors and chambers are always full of tourists, scouts and anthropologists. The hippest way to play the game is to trace - intellectually or instinctively - a backwards path through the labyrinth, not to uncover the origin of the quotes (pedants and purists already do that), but to demonstrate either a knowledge of, or a feel for, where the echoes are heading.

Trained as Picture editor for Con& Nast, and presumably adept in this process of part-intellectual part instinctive linage selection, Kruger plays the game well. Her work between 1981 and 1984 perfectly collaged retro mass imagery onto text banners of suitably ambiguous political rhetoric. The retro aesthetic was already strategically employed in post Punk fashion, music, and graphic design in the late seventies, and was an extension of Eduardo Paolozzi's collages from the late forties and early fifties. While much French theory was heaped onto her work, not much note was made of her real triumph: fine tuning the retro aesthetic by successfully mutating the formalist techniques of John Heartfield's anti fascist photo montages from the thirties, with a Rod Serling voice over narration straight out of The Twilight Zone from the fifties. The greater appeal of Kruger's work - the potential resonance of its humorous commentary in the public arena comes from this mix of referencing political art and sci fi TV, rather than her skill in selecting images, her ideologically sound content, or her wit in combining the two.

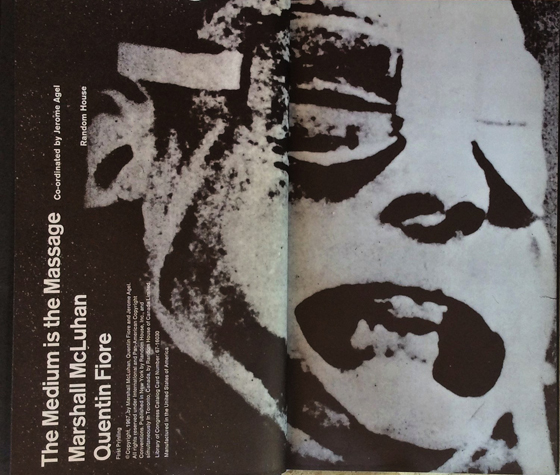

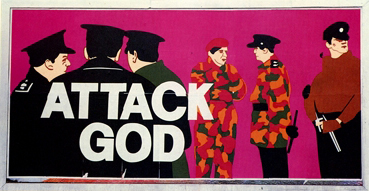

Kruger's style and method established during this period developed two particular instances of image-text ground work. The first is Marshall McLuhan & Quentin Flore's The Medium Is The Massage (1967), which was designed as "an inventory of effects" to graphically depict the functional operation of the book's title - the title page in fact uses an image used by Paolozzi for his Wind Tunnel collage of 1950. A sarcastic dandy whose views on the media eventually brought advertising agencies courting his views on consumer psychology, McCluhan stands as a precursor to Jean Baudrillard's concepts of simulation and effect in contemporary culture. The second instance relevant to Kruger, is the lesser known postcard work of John Stalin and his company The People's Police. Easily identified by their checkered borders, Stalin's work was a very influential approach to collage which typified much Punk and post Punk graphic design, particularly for record covers. More importantly, Stalin's postcards (published as three major series in 1980, 1981 and 1983), were often based on a single unaltered image. onto which was laid a text banner which instantly transformed one's interpretation of the image.

Only occasionally exhibiting in galleries, Stalin preferred to work as a producer of postcards and will unfortunately obtain at best a small footnote in art history. Kruger's career change from commercial media to fine art, has more far reaching consequences. Like Stalin, Kruger's real skill was to select images basically free of reference interference: passages devoid of immediate references which the viewer must recognise and pass through to arrive at a meaning This deliberate lack of specificity (in work which dates from the early eighties) was a manoeuvre which induced a multiplicity interpretative possibilities and ambiguity of effect. Yet once it was translated into the discourse of fine art the same lack of specificity serviced a vacuum (popular culture as anonymous and indiscriminate), and was filled in with the identity of Kruger as author. Fine art discourse has traditionally exploited such a gap to extol creative virtue, and in this instance to credit Kruger with the total effect of her appropriated imagery. Much postmodern art which deals with popular ulture in fact operates in this way - de-contextualising, and then re claiming it on a higher level.

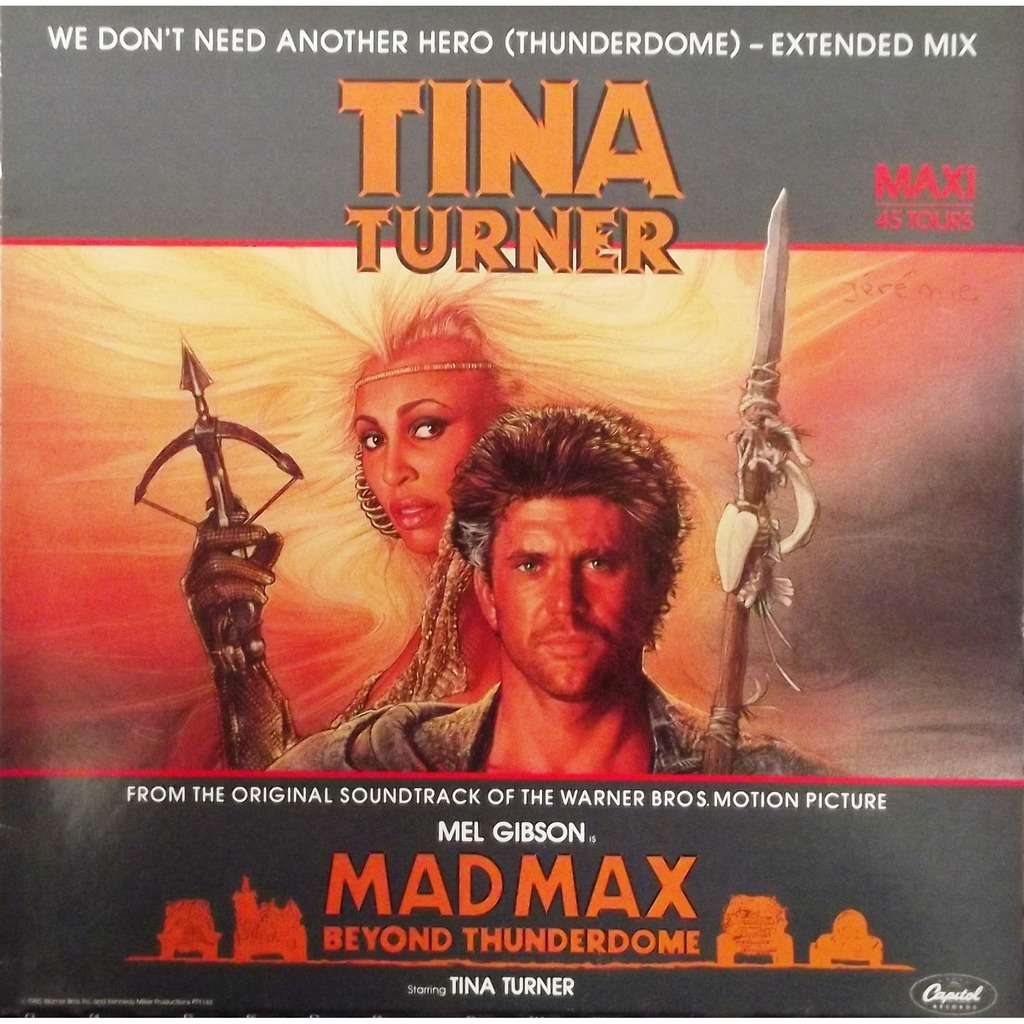

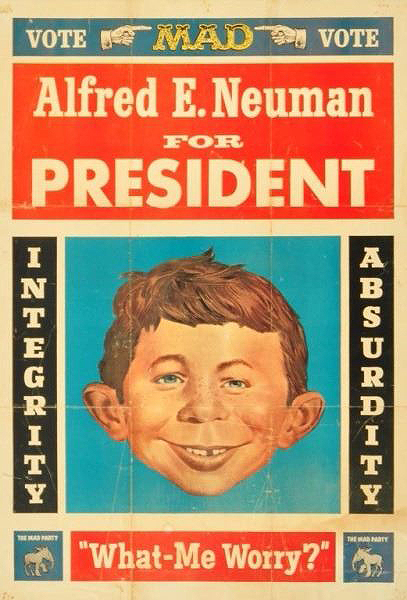

Kruger's later work plugged into contemporary popular culture more directly, but so much of the critical appraisal of works like We Don't Need Another Hero, and What, Me Worry? (all 1987), appeared ignorant both of the immediate references and colloquial mode of address being used, as well as the satiric bite of the original. For example, We Don't Need Another Hero (the title of the theme song to Mad Max III: Beyond Thunderdome) was held to champion feminism, as if Tina Turner either didn't exist or was somehow not doing the same; and What, Me Worry? (the phrase captioned for promotional images of Mad's Alfred E. Neuman) was supposed to critique social irresponsibility, as if Mad magazine either didn't exist or was somehow not doing the same..

My point is that while Kruger is effectively critiquing culture, the very culture she critiques is already critiquing itself, from Mad to Mad Max. Inasmuch as her previous work was deliberately unspecific (in the tradition of Heartfield, Paolozzi and Stalin), this later work is very specific so much so that many art patrons either did not note the immediate references or thought them irrelevant. There is also something awkward about the way in which Kruger's work foundered, and was confounded by, certain aspects of communication overload in popular culture. It alerts us to some of the ways in which that strategy can be confused, co opted or corrupted by fine art's distanced perspective on popular culture, and also how postmodern artists are forced to juggle with these politics of representation.

As problematic as it is, the value and power in Kruger's later work is in its implicit critique of the 19th century notion of the artist estranged from society, heroically expressing his innate individualism. This critique begins with Duchamp and dada, developing through Hamilton and the British Independent Group, and peaking with Warhol and American Pop - a lineage to which Kruger and most post-Pop Art is aligned. While this lineage has been circumscribed as a trajectory of dandyism (the wilful celebration of self consciousness, perversity. irony, etc.), it has its roots in a politics of refined taste, and the inflated value system of the Romantic aesthete. It is no wonder then that Postmodern art is so critically hinged on the promotion of bad taste, gross humour and blunt sentiments. Kruger's later works - and Heathers, for that matter - deliberately ape those traits and appeal to their primary audiences (respectively, the postmodern arena and the cult market), through a contemporary reworking of strategies like parody, pastiche, burlesque and satire. Consequently the gag, the joke and the point, have replaced the message, the moral and the viewpoint - not simply through the degeneration of discourse and the collapse of meaning, but as a reassessment of the fundamental purposes of satire in social commentary, art practice and cultural referencing.

The dadaists were the first of the Modernists to mine satire's potential for triggering antagonistic humour through social critique. Duchamp was dada's most eloquent speaker and best comedian, and far from simply being witty and cryptic, he was actively engaged in sourcing colloquial modes of humour. For example, the unknown object entrapped in the ball of twine in With Hidden Noise (1916), recalls the bemused giggle of children being taunted with mystery; the toilet urinal of Fountain (1917), invokes toilet humour: the hat rack fastened to the floor for Trap (1917), alludes to the practical joke; and the vandalised Moira Lisa of L.H.O.O.Q.(1919), promotes ridicule through defacement. Many of Duchamp's assisted readymades manipulate these resources to make the viewer the butt of the joke. Much dada art is now perceived as overtly politicised absurdism, but Fountain will always be as base as it first appeared to the critics of the Society of Independent Artists. As a prime example of toilet art it stimulates the self reflexive appeal of primal toilet wall scrawl: "If you read this you're a dickhead!"

Certain strands of conceptual art throughout the sixties and into the seventies returned to this intersection of linguistic reflexivity, anti aestheticism and dumb arse humour. Artists such as Joseph Beuys, Joseph Kosuth, Les Levine, Christo and Chris Burden, were often motivated to express black humour at the expense of the viewer. Prior to Kruger's rise of the billboard, Levine had explored its potential as a site for amplifying his work and parodying himself as a used car salesman in the art world. Here he could present himself as a character in much the same way that Beuys played the role of Beuys the artist in his lectures. Kosuth used linguistic constructions to humorously mirror a viewer's search for explicative meaning in the anti object world of contemporary art, laterally connecting with funhouses and their use of distorting mirrors. Christo's greatest joke plays on himself and the viewer, as his wrappings mimic the industrial coverings which usually connote that "work is in progress" - an eternal, frozen progress never to be unveiled. Chris Burden - well, if you don't think there's anything firmly about Burden having his body wrapped in heavy blankets and left on a busy L.A. freeway to see if anyone would run him over, then perhaps you've missed the kind of joke so typical of the nut who on a dare, tries anything for a laugh at the end of the week.

In a way, Yves Klein - a leader in neo dada and a prophet of Pop - went further than any of the above. Famous for his Anthropometry paintings which used nudes as flesh paintbrushes (satirising the macho chauvinism and ballsy bar room camaraderie of the American Abstract Expressionists), he apparently contacted film producers Gualitero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi in order to be included in Mondo Cane (1962). The first mondo movie or shockumentary, Mondo Cane features natives eating insects, fishermen slaughtering sharks, kids polishing skulls in catacombs, women wearing live bugs as jewellery, religious fanatics cleaning stairways with their tongues, men being chased by a bull down a street and some crazy artist who paints with his models. Dressed in formal suit and tie and accompanied by a string quartet (for inspiration says the voice over narration), Klein played the crackpot artist to the full. Unlike Gilbert and George, whose droll performances either operated within the gallery environment (where anything goes for art), or in the guise of public mime buskers (where anything goes for money), Klein's cameo in Mondo Cane sees him stripped of his vestiges as a serious conceptual artist. For example, the string quartet in reality played one of Klein's own proto minimalist "Monotone Symphonies", but the scene is overdubbed with the Top 10 hit theme, "More". Klein appears as an anonymous representative of the wild and weird world of modern art marking his role in Mondo Cane as his most serious comment on how meaning is generated in art through artistic identity.

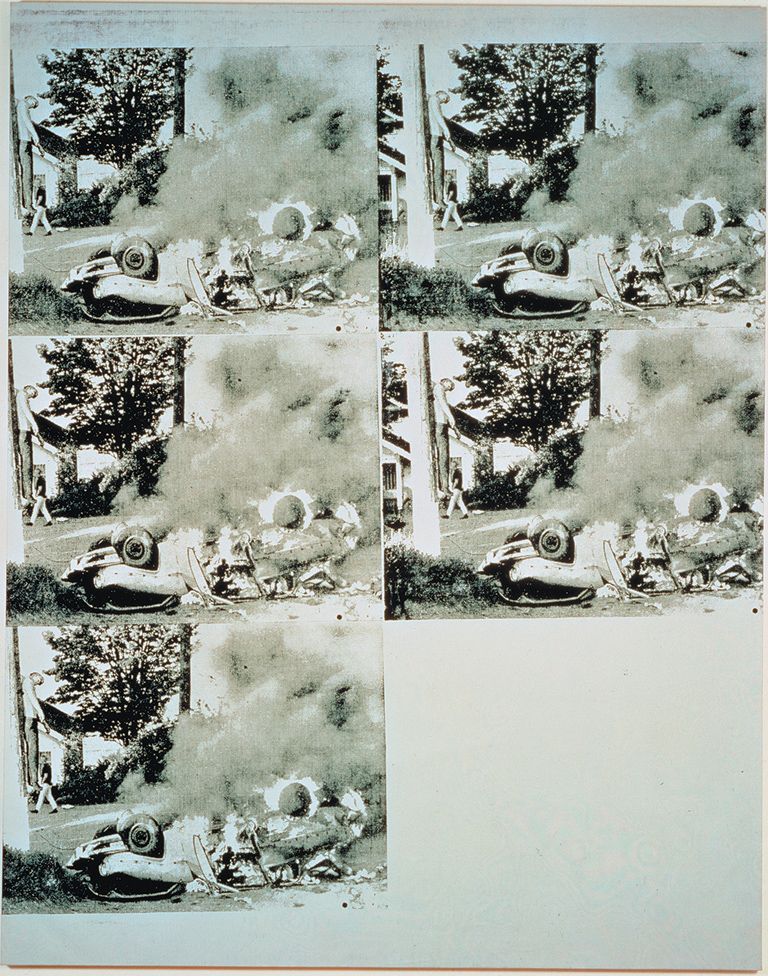

The dada legacy is continually manifested in conceptual art through displays of how far an artist will go to make art, hence the ambiguous mix of the heroic romantic and the impulsive looney, living on the edge and working as an outsider - or as McLuhan put it: "Art is anything you can get away with". Though associated with Pop Art, Warhol can be seen similarly insofar as his work was primarily designed to create an environment within which he could play artist. His ultimate scheme became to re invent popular culture as theatrical backdrop to this display, and he knew that once art becomes popular it was destined to be consumed by popular culture. Warhol played the role of artist as a fundamental contradiction of the status the name implied. A lateral connection might illuminate this further. Compare Klein's famous photo of his Leap Into The Void (1962) with Warhol's White Burning Car (1963): Klein used his photograph of himself in a mock up of a newspaper front page; Warhol used a similarly shocking image of a body thrown through space not staged as an artistic spectacle, but featured in a morbid newspaper photograph of a commonplace apocalyptic accident.

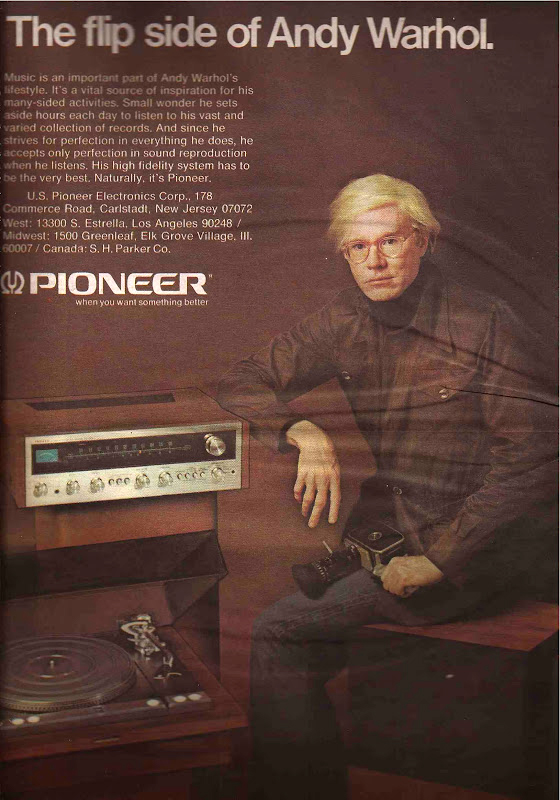

While both Klein and Levine ironically advertised themselves as artists - communicating predominantly to an art audience the nature of the artist as product - Warhol's Pop strategy was to communicate himself as all artist to everyone but an art audience. He did this by presenting himself as a charlatan, and thereby provided popular culture with its cynically desired image of the artist. Artists often lose sight of the fact that whenever art enters or crosses popular culture it is allowed to do so only for ridicule - something of which Klein may or may not have been aware. Very few modern or postmodern artists have ever been able to really communicate to the masses that art is futile, redundant, arbitrary and meaningless: they know that already. One must not forget what a field day the American press had with the Armory Show in 1913 in New York, not unlike the manner in which their French counterparts reacted to the first Salon exhibition of the Fauves in 1905. Both were conservative reactions against formal methods of artistic depiction, Duchamp's pre dada Nude Descending A Staircase (1912), being a "serious work of art" and a formal exploration of the time-space relationships between Cubism and the then forming Futurism. His readymades come after this potent taste of popular culture's taste in art, indicating that Duchamp learnt the first lesson in controversy: you don't court it - it catches you. Warhol courted controversy by letting it think it caught him. His cameos and name lending in advertisements are then logical instances of his surrender to popular culture in the name of popular culture, allowing himself to be exploited not as an artist but as someone who is famous for being all artist.

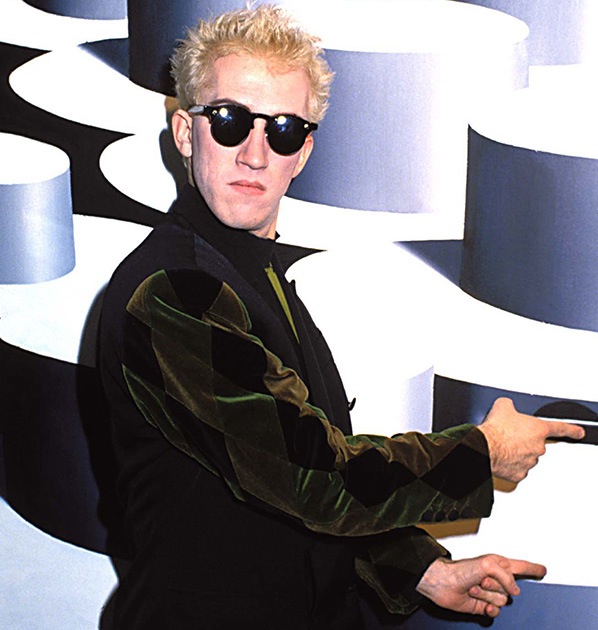

A good example of a textbook Warhol, Mark Kostabi, is famous for trying to be famous as an artist - but that's where the Warhol connection ends. Calling him the next Warhol, is as dumb as saying that Taylor Dayne and Debbie Gibson would each be the next Madonna. To posit Kostabi World (his factory run more along the lines of third world cheap labour, than Warhol's recreation of Hollywood's dream factory), as a sign of postmodernity's industrialisation of simulation is pure folly. Kostabi has desperately played the American media since the mid eighties, receiving unending coverage by an endless supply of journalists who failed to distinguish between Warhol, and Kostabi playing Warhol. Yet Kostabi proves himself useful as a ghost come to haunt postmodern art with the materialisation of its referencing, not of popular culture, but of the much vaunted collapse of art and culture. Kostabi is a walking, talking, mass of that rubble, feigning the mad artist for those who see no practical difference between Warhol and Van Gogh. In the end, he affirms what popular culture already knew that all modern art is made either by crazies or bad comedians, a charade Kostabi embarrassingly enacted for 60 Minutes, by wearing his harlequin suit, playing the Court jester sitting atop a traffic light on Broadway.

Kostabi has never demonstrated any knowledge of the crucial difference between courting controversy and letting it catch you. His inability to differentiate these two modes of hype throws him into orbit precariously close to Kruger. His Kostabi-isms (his pre packaged you may quote me quotes which paraphrase Warhol and McLuhan) sound very much like her post 1985 - or is it the other way around? Compare: "I Shop Therefore I Am" (Kruger). with "I Am Bought Therefore I Am" (Kostabi). Or try guessing who said what: "When I hear the word Culture I take out my chequebook" and "Paintings are doorways into collectors' homes". Despite his dumbness in aping Warhol is Kostabi hipper that Kruger? In a roundabout way, we have now introduced a fourth figure into the Heathers/Kruger/Descartes instance of referencing. Perhaps some viewers of Heathers figured Kostabi as the author of the postcard. Perhaps they are not all that wrong. And perhaps Kostabi works as a blockage in Kruger's strategy of blending her voice with the colloquial, because that terrain is so saturated by others making similar claims. Clearly, this is why Jenny Holzer's text-o-grams have remained so defiantly anonymous, able to dematerialise in any media space, leaving no trace of who said what, and whom is being referenced, of creating an overload of reference interference, in place of the gap caused by her absence.

While we're on the subject of distinguishing the identities and strategies of artists and charlatans, it would be criminal not to look at Ken Done. Essentially an interior designer who took to the shopping malls, intent on wallpapering popular culture with the prefabricated fabric of his identity, Done poses further problems as to why and how we can celebrate art, popular culture and/or the possible collapse between the two. Done is, literally, a material effect - a movable stain of artistic identity that can be overlaid on anything: T shirts, cups, tea towels, bed sheets, as well as name products like Australis perfume, Swan beer and Dulux paints. Conscious of his market boundaries, he applies his staining to those items which inhabit the vacuous domestic stratosphere plotted by interior design, and readily accept any identity given them. The claustrophobic proximity of art and popular culture is visible in how Done's vacuous stratosphere is conceptually akin to Klein's void - used as the stage for his artistic projection, and practically akin to Warhol's environment - designed as a theatrical backdrop for his cultural performance.

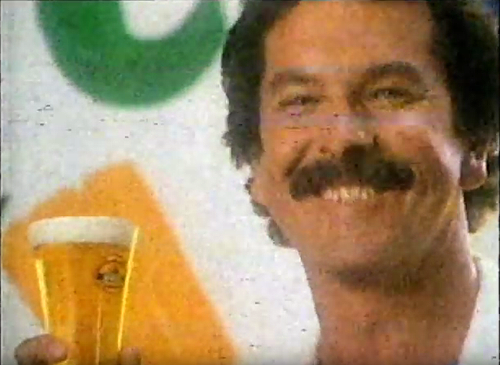

On this saturated plane of the art cross over, Done's marketing of his artistic fabric is as crucial a manoeuvre as Warhol's franchising of his Pop identity. In one of a series of advertisements for Swan lager, Done is depicted as one of Australia's contemporary folk heroes. As the insipid Mo Jo style of heart felt jingle intones "They said you'd never make it," a group of (presumably Australian) art critics nod their heads dismissively at Done's paintings. Cut to Done in Paris (!) at a sell out exhibition of his work. The little Aussie battler shows them, and us, how the severed head of the tall poppy can make it in a scenario that could have been directed by Frank Capra. The Swan advertisement pays dribbling lip service to Anglo American mythologies of modern art: France as the centre of the art world; the artist as a struggling hero paving his dues and sticking to his guns while the masses ridicule him, etc. Of Course the only place Done has made it is in a realm recognised by the likes of Swan Lager - that is, a media space which feeds off the media potential of the Done marketing machine.

The Dulux paint advertisement featuring Done exhibits a more tongue in cheek approach, by cleverly confusing issues of professional art careerism and the industry of interior design. This confusion - itself a sign of postmodernism exploited by the advertising industry - is embedded in an ambiguity generated by parodying Dulux's old image, associated with the parental folk figure of Rolf Harris, and Dulux's new image projected through the golly gosh hokum of urbane Ken Done. On reflection, the intersection of Rolf Harris and Dulux paints is a pre postmodern conflation, especially if one interprets Harris' iconography - the macho heard, the dripping brush, the ocker tone, the buckets of paint, the gawdy mural as all allusion to Pop's own jokes at the expense of the Abstract Expressionists. Similarly, Done's Dulux ad infers traits of Pop and post Pop, marking his endless production of interior design in the name of art ("Love your new painting, Ken") conceptually close to Pop - Warhol's Cow Wallpaper (1966); Lichtenstein's Modern Painting and Modular Painting serial panels (between 1967 and 1969); - and post Pop - Richard Prince's reproductions of high gloss advertising photography; Allan McCollum's production line pre framed paintings of black; and Jeff Koons' editions of cast figurines for the domestic mantelpiece.

Still, there is something limp and prissy about Done's elbow ribbing Dulux advertisent, a quality made apparent when one sees the more gutsy Dupont Stainmaster carpet advertisement featuring Pro Hart. Consider: if Warhol feeds off the masses' cynical view of art; Kostabi their detached view of art; and Done their pragmatic view of art, then Hart feeds off the masses' altruistic view of art that it is the activity of supplying beauty on demand. Pro Hart is a real artist - an all-Australian landscape painter. Rather than commodifying his work like Kostabi, or marketing it like Done, Pro Hart industrialises the process of painting, mass producing original signed landscapes like a small businessman hocking the wares of his cottage craft to the masses. For Hart's audience he delivers the real thing.

His Kleiman performance in the Dupont Stainmaster carpet advertisement is not a parody of his own industrial practice, but a straight forward piss take on the theatrical excesses of modern art - which to Hart and his audience means Jackson Pollock (whose $3 million sale of Blue Poles to the Australian National Gallery still stings their tax returns). Hart's cantankerous goo mulched by his flabby girth, is a total inversion of Klein's fraudulent liquids gleefully splashed about by his naked models. Here is a severely unironic statement embedded in an advertisement working under the guise of extreme irony. Note also that the bland, beige Dupont Stainmaster carpets are being pushed mainly for their ability to resist staining, and are therefore diametrically opposed to the comparatively avant garde aesthetic promoted by Ken Done for Dulux and stained by his sense of design. If Duchamp was at his self mocking heart seriously stating "If you read this you're a dickhead," Hart replies to the progressive impulses of modernism in an equally terse, colloquial voice - "You've got to be fuckin' kidding". Radically opposed, they each nonetheless hit the dead centre of the art/culture mutation with dead pan humour and deadly accuracy.

Even though I am only touching on some of the base mechanisms of modern art (referencing, critiquing, quotation), which by the laye fifties were irretrievably enmeshed in the gears of commodification, exploitation, industrialisation and mass production, the few artists discussed above collectively project an interactive energy field so intense it is little wonder that the customised combine of neo dada, Pop, and post Pop, has had such little impact on the socio cultural terrain across which this dynamo of art and popular culture mutations has already been spinning. Its energy is the stuff of dialectic gags, and deconstructed punchlines all fuelled by that cinematic effect peculiar to contemporary cultural referencing, re evaluating the purpose and function of satire. Mobilised by this dynamo, art and culture have not collapsed into each other - they've gone walkabout: across new socio cultural plains; along frequency bandwiths of media airways; into expanded and destructured audio visual sensurround fields; and through immaterial networks of negative space. Surveying this media saturated panorama, one can't help thinking: "Culture changes; artists don't".

The aim of this essay has been to lose track of the trajectories of art's trailing of popular culture, and popular culture's trailing of art, by combining the likes of (in order of appearance) Michael Lehman, Barbara Kruger, Alfred Neuman, Joe Dante, John Hughes, Marcel Duchamp, Marshall McCluhan, Eduardo Paolozzi, John Stalin, John Heartfield, Rod Serling, Les Levine, Christo, Yves Klein, Gualitero Jacopetti, Andy Warhol, Mark Kostabi, Jenny Holzer, Ken Done, Rolf Harris, Richard Prince, Allan McCollum, Jeff Koons and Pro Hart. All their voices authorial, political, satirical communicate through coughing and spluttering in an atmosphere composed by analytic smokescreens, laughing gas pellets and political stinkbombs. Everyone is a critic; anyone can be an artist; and they all want to be comedians.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.