Manga & Anime in Australia

Manga & Anime in Australia

Report

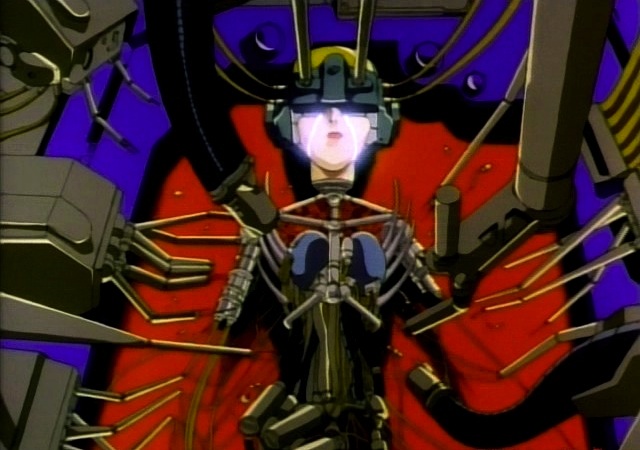

published in Commickers No.6, Tokyo, 1997Let's face it: most manga and animation is fanboy fodder. The successful MANDARAKE stores could easily be called OTAKUDARAKE. They are usually full of worshipping fans trapped in juvenile flights of fantasy. In the West, identical facets govern fandom. Over the last decade, the most popular Japanese animations in the West resemble sitcoms (from RANMA 1/2 to TENCHI MUYO) or heroic sagas (from GUNDAM to DRAGONBALLZ). Only recently - with works like GENOCYBER and GHOST IN THE SHELL - has there been a growing awareness of the thematic depth and multicultural complexity that hides in much Japanese animation.

I often find myself caught in the middle. I know that Sonada Kenichi is hardcore otaku, but I also think there are profound moments in both the GALLFORCE and BUBBLEGUM series. But this awkward middle ground does have its advantages. It allowed me to curate a major exhibition (called KABOOM!) on postwar American and Japanese animation for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney in 1994. The exhibition profiled the work of Tezuka, Miyazaki, Sonada, Otomo, Takahashi, Terasawa and others and was seen by over 79,000 people. This 'high art' profile of animation has had some impact locally in diffusing the typical Western view that animation can only be puerile and bereft of value.

Japanese animation, of course, had filtered through to Australia well before this. The comic stores first into Japanese manga were in Sydney (THE LAND BEYOND BEYOND and COMIC KINGDOM) and Melbourne (MINOTAUR and ALTERNATE WORLDS). They stocked translated publications from VIZ, MARVEL, EPIC and ARTIC PRESS. These were eventually augmented by imported American NTSC videos. (Australia uses the PAL system.) Across this same time, the Chinatowns of both Melbourne & Sydney developed thriving Asian fan networks. The largest is in Melbourne, serviced by HOBBY JAPAN's two stores which specialize in garage kits as well as running a membership video library. Most of the titles are subbed in Mandarin, but one can either get friends to translate them, or download translations off the Internet. The past few years has seen these Asian stores expand considerably. The Western comic stores meanwhile have become narrow and more obsessed with nostalgic Marvel/DC superhero drivel and novelizations of the exceedingly facile STAR WARS trilogy.

Outside of the "dasai" (uncool) world of garage kits clubs and comic book stores (the Australian slang is "daggy" - it refers to the shit that hangs off the arse of sheep), Japanese animation is very hip in the techno nightclub scene. From nights called BUBBLEGUM CRISIS to live acts called GUYVER to the fashion label DANGERFIELD using a copyright-infringing image of Tetsuwan Atom on its sale bags, Japanese animation is visible and celebrated. AKIRA and the proceeding hard-sci-fi animations have been a huge influence on this future-dreaming scene. In 1995 I curated a retrospective on the work of Osamu Tezuka for the Melbourne International Film Festival which was wildly successful, more due to the techno scene more than the fanboy scene. Last year's festival kept tapping into this audience with screenings of MEMORIES and SILENT SERVICE, though they were nowhere near as popular as Tezuka's work.

The SBS network - the Special Broadcast Service which shows subtitled programmes from around the world - has also picked up on the growing interest in Japanese animation. SBS aided in some of the subtitling for the KABOOM! exhibition, and has since screened SPACE ADVENTURE COBRA, NINJA SCROLL and PATLABOR 1. Though not as high profile as Hong Kong action cinema, Japanese animation is certainly broadening its audience through these broadcasts. Concurrent with this, the Australian branch of MANGA Video started releasing titles from the UK label in 1995. Numerous video stores around the country now stock a wide range of their titles, from parts of the infamous UROTSUKIDOJI series (censored versions in Australia) to the more respectable GIANT ROBO series. KISEKI followed suit in 1996 with the remaining installments of UROTSUKIDOJI and titles like THE SENSUALIST and PLASTIC LITTLE.

The main problems with watching Japanese animation in Australia is (a) the time it takes for the product to reach here in English, and (b) the costs involved in transferring masters from NTSC to PAL. Unless one is plugged into the Asian fan networks, one has to wait until - usually - an American company (like US MANGA CORPS, VIZ or ANIMEIGO) does a dubbed version which is then purchased as a translated-product by an English company who the makes a PAL master which is then easily picked up by an Australian distributor.

Interestingly, the local comic scenes in Melbourne & Sydney - small as they are due to resources and the high cost of printing in Australia - have not formally incorporated Japanese animation & manga into their style. While most of the underground comic artists are huge fans of Japanese animation and manga, their drawing skills render them incapable of executing such a style in their own work. As such, Australian underground comics tend to be more influenced by the American underground work of Dan Clowes, Raymond Pettibone, Jim Woodring, Julie Doucet & Richard Sala. Clearly, the high level of draftsmanship in the work of Otomo requires great skill and committed practice. Underground comic culture does not so easily provide one with a living to hone one's skills to that degree.

All in all, the presence of Japanese animation and manga is noticeable in Australia, though there is still room for a fuller understanding of its history and the culture from which it comes. Through comic and video stores importing translated manga for a small but enthusiastic clientele, and cultural events like the Melbourne International Film Festival programming Japanese animation, the popularity and appreciation of Japanese manga and animation will continue to grow. Our appetite is strong.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © Tony Takezaki & Artmic.