Essay

Avant-garde Meets Mainstream: The Film Scores of Philip Brophy

published in Screen Scores: Studies in Contemporary Australia Film Music AFTRS Publishing, Sydney © 1998

by Philip Samartzis

Cinema continues to privilege vision over audio, generally reducing film sound to a few cliched gestures, and promoting the notion of the transparent soundtrack (see Kalinak, 1992, for example). Philip Brophy's approach to composition and sound design for narrative cinema communicates a clear loathing for conventional applications of film sound. In Brophy's soundtracks, the aural preconceptions which inform most approaches to narrative sound design and composition are challenged by including contemporary music techniques such as dissonance, counterpoint, rhythm, sampling and synthesis', and eschewing the dominance of nineteenth century romantic orchestral structures, performance, harmony and instrumental timbres. Basic sound techniques of synchronicity, placement, layering, shaping and movement, usually determined by the demands of vision, are individually reconsidered in the organization of more complex spatio-temporal relationships.

Brophy's soundtracks are sites where his passion for twentieth century music development, performance and production converge. Through a considered examination of how different musical genres, sound production techniques and concepts have developed within this century, Brophy is broadly experimenting with methods which have the potential to extend and enrich the vocabulary of film sound production and perception. Through these explorations he is attempting to emphasize 'equality' between audio and vision. Removing conventional emotional mechanisms, where meaning is no longer simply discernible by the visual dynamic, and by emphasizing a plurality of meaning conveyed by a dense sonic construction, Brophy's sound designs and scores encourage an active engagement with the narrative. By examining four films either directed and/or sound designed or scored by Brophy namely Salt, Saliva, Sperm & Sweat (1988), Body Melt (1992), Only the Brave (1993) and Maidenhead (1994) — I will investigate the conceptual themes and technical considerations which have preoccupied him, and demonstrate how his scores differ from 'the mainstream'. Brophy's approach and musical production may no longer be considered avant-garde within the arena of musical composition and performance, yet within Australian soundtrack composition, and as musical and sound production and performance for film, his work and conceptual concerns are unusual to the point of controversial.

Before turning to an analysis of specific works, some details of Philip Brophy as a musician, filmmaker, writer and curator are relevant. Brophy has been engaged in the exploration of different forms of media since the 1970s. He has curated several animation based retrospectives including on Osamu Tezuka retrospective (44th Melbourne International Film Festival, 1995), ond KABOOM: Explosive Animation from America and Japan (Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 1994). He has authored and published collections of essays on contemporary media, culture and popular icons. He has been involved in experimental music bands like Tsk Tsk Tsk, and has released numerous recordings on his own Present Records label including 'A Fistful of Rock' (1989), 'The Abdominal Wall of Noise' (1989) and 'The Present Compilation' (1990). The variety of media that he has explored have informed his film productions and approach to soundtrack composition. While his experience as a film composer is limited, he is considered to be particularly experimental in his soundtrack design and composition. In addition, he has gained a reputation for his analyses and critiques of sound production. He has written and spoken about numerous aspects of film and sound including 'Aspects of Sound and Music in Indigenous Cinema', 'Spatial Logic and Dimensionality in Film', 'Sonic — Atomic — Pneumonic: Apocalyptic Echoes in Japanese Animation' and 'The Sound of the Look of Citizen Kane'.

Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat

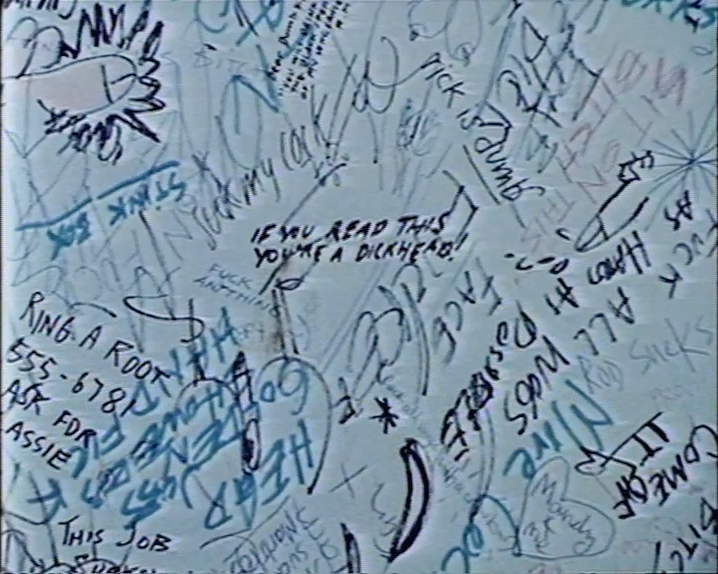

Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat is an essay-style film investigating the visceral and intellectual connections between images and sounds of sex ond violence. Funded by the Australian Film Commission (AFC) and completed for release in 1988, the film is directed, edited, sound-designed and music-scored by Philip Brophy. The 16mm film release is in mono; the video release is in stereo.

Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat contains the most artificial sound design among the films discussed here. Shot with no recording, Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat's total soundtrack was constructed in post-production. As such, it follows the stylised post produced dialogue recording procedures developed at Cinecitta, Rome (which became evident by the late 1950s ), and within animation generally. The post produced soundtrack has become the standard working method in narrative cinema, enabling sound effects, atmospheres and dialogue to be recorded and processed in an acoustically controlled environment. But Brophy is less interested in high fidelity, 'well recorded' effects than in the extreme processing and manipulation of sound which the studio can afford him. The recording studio as instrument is a concept explored by many music producers including Phil Spector, Tony Visconti and Bill Laswell in the discovery of new sounds and timbral relationships.' Brophy has used this working method consistently in each of his films. As Brophy notes:

"In Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, I devised a totally non-synchronous means of working with multi-track recording whilst watching a fine-cut image. To facilitate this, the film was broken down into about 26 sections lasting between one and three minutes (so as to maintain synchronization between sound and image ). A total of 32 tracks were used via a series of four submixes of eight tracks: one for music; one for atmospheres; one for sound effects; and one for Foley. The music was composed on analogue multi-track, using Yamaha SPX 2 samples and Amiga 500 8K samples of body sounds and noises, then performed musically on a keyboard. Additional Yamaha DX7 textures were also incorporated. The main synching was required for the sound effects, atmospheres and Foley. Most sound effects were recorded in the studio and used rudimentary effects processing, plus a now-archaic Amiga 500 for 8k sampling — the harshness of which greatly contributed to the film's piercing textures. The Foley sounds were done in long, live slabs, using seven microphones for various parts of the body: two for feet movement, two for hands/chest noise, one close-mic for breathing, and a stereo binaural headset for general upper-body presence. Engineering was performed by Philip Samartzis, Ian Haig, Mal Phillips and Steve Edwards, although the final mix was my own."

Brophy's synthetic concept and sensibility, combined with the non-synchronous aspects of Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat's sound design, forms a very unusual, at times overwhelming, sonic experience. This is partially due to the technical limitations in post-production which was based on a very loose synchronizing procedure between multi-track tape machine and video deck. The synthetic aural environment is further extended by the artificial quality present in the general look, logic and dynamic of Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, extending the film's vocabulary of exaggerated gestures and exchanges, while consolidating the connection with animation beyond just the overall sound design. Embellishing this association with animation are the banal institutional office-style film locations, combined with lighting, camera positioning and framing, which tend to exaggerate the facial features of the lead actors (Phillip Dean and Jean Kitson). Such techniques instill a sense of ugly realism into the stylised movements and gestures informing the narrative and create a complex dichotomy between reality and fantasy, comedy and horror.

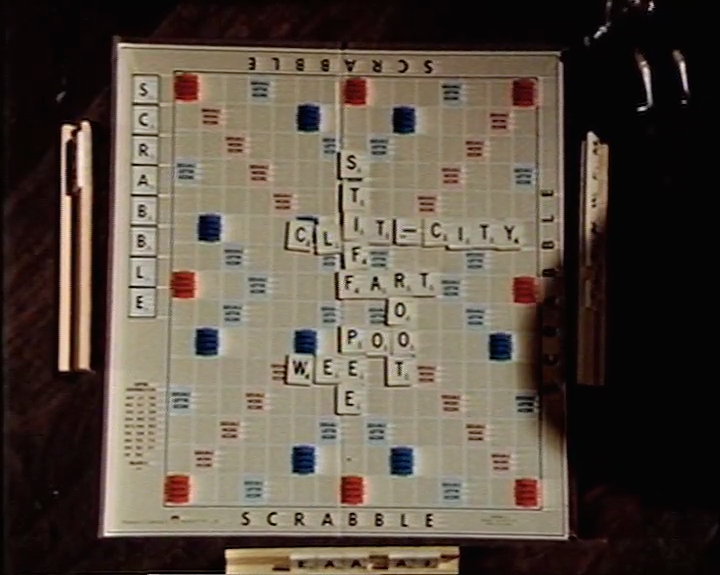

These exchanges and explorations occur in Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat's experimental narrative structure, which breaks down into four themes as suggested by the title. Salt examines ingestion; Saliva, speech; Sperm, sexuality; and Sweat, violence. The cyclic motion of the narrative is emulated by the music score which is constructed from a series of simple, stark electronic melodies. The placement of the cues are at similar points within the four narrative themes, further emphasizing repetition. Extending this structure to the sound design, each theme stresses a different component of the soundtrack. Salt has an emphasis on music; Saliva, voice; Sperm, breathy and moist music and sound effect textures; and Sweat, percussive timbre. This experimental structure, reminiscent in some ways of Kurosawa's experimental narrative structure developed for Rashomon (1951), helps emphasize different aspects of the soundtrack as they thematically connect with the narrative structure. As basic dramatic events are repeated in each section, a different aspect of the aural environment is emphasised, creating a new sonic experience, and altering the perception of the repetitive actions and locations.

The general tone of Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat is euphorically artificial despite the fact that original sounds are all bodily sounds. As Brophy notes in an interview with Tom Ryan:

"... apart from a few instruments, the music is entirely made up of body noises, rhythms, beats made up from grunts, hand slaps, skin being rubbed, and so on ... The idea was to reinforce, on a subliminal level, the continuing presence of a body. Right through the entire soundtrack of the film is the sound of somebody breathing. Even over the computer text. It's something usually left out of cinema (except pornography), unless the point is to make the audience aware of the character being unbearably close to the camera. More than anything else, this continuous breathing through Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat gives the audience the sense that they are inside somebody's skull." (cited in Ryan, 1989: 33).

Nearly all sounds appear to be processed in some way with few concessions to naturalism. Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat's sound design is based on an examination of the sonic character of each environment appearing within the film. The soundtrack is designed to reconstruct each sound within these environments by either faithfully re-recording the exact event or, more often, by the rendering process (see Chion, 1994: 109-1 14) with the benefit of multiple microphone placement and equalization extending the spatial dynamic of the effect. The rendering technique is one which exchanges a real sound with one derived from an artificial process, or from a process of substitution. This gives the artificial or substitute sound more detail and character than the original effect. When combined with an image, the experience is perceived as being more natural or realistic, in cinematic terms, than the original sound itself. Gunshots (Taxi Driver, 1976 ), punches (Rocky, 1976) and karate kicks and punches (Enter the Dragon, 1973) are seminal examples of this process. The recorded sound effect is then subjected to artificial textural enhancement, conditioned by an assortment of dynamic, spatial and modulating processes which intensify the 'presence' of each sonic event. In film analysis, 'presence' is a concern for )be sound loca6on recordist and generally heard in the subtle sonic profile of particular locations, created by 'the movement of air particles in that particular volume' (Handzo, 1985: 395). Presence is a psycho-acoustic phenomenon that offers a sense of a specific location beyond actual subtle ambient sounds that can be silenced (such as those emitted by fluorescent lighting, air conditioners, etc ) and beyond the precise reverberative qualities of the room. Handzo associates presence with 'room tone' which is never the same in two rooms. In film, he argues, room tone is significant for the audience perception of space and explains that 'there is never no sound even when nothing is happening on the screen. The soundtrack "going dead" would be perceived by the audience not as silence but as a failure of the sound system' (1985: 395). The creation of room tone is needed where dialogue replacement has occurred or, as in Brophy's usage, where the soundtrack is created in post-production.

Brophy uses presence in post-production to create the particular sonic profile, timbre or texture of sound elements unrelated to actual location. An examination of voice recordings will best demonstrate his process of artificial textural enhancement in Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat. All vocal performances were recorded in post-production using a binaural stereo microphone headset, a spatialization process which can dimensionally place sound within a spherical soundfield around the head. Some of these recordings were mixed directly into the Saliva component of the soundtrack, while others were dynamically processed by the application of compression or noise gating, or routed through spatialising or modulating effects into other sections of the film. In Saliva, compression was used to create constant, close vocal textures by removing peak signals, while noise gating created percussive effects by the truncation of faintly decaying events. In addition, sampling technology was employed to extend the sonic vocabulary of the film. The sampling process enabled sounds to be manipulated (edited, looped or reversed ) and then triggered by a Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) controller, extending the performance beyond a simple recognisable acoustic event. The stages of process outlined tend to remove the subjective origin of the sound, leaving an essence which suggests a particular quality or meaning. In Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, distilled sonic textures simply augment themes like sex with a disembodied moan, gasp or sigh, not unlike certain genres of pornography in which the soundtrack is reduced to a carefully composed mix of post-produced utterances texturally conveying sexual engagement.

Sampling also plays an important part in the development and performance of the music score. Many of the cues were created from instrumental explorations developed from body-based samples, extending the film's preoccupation with the body into the grain of the score. The strength of sampling technology is its capacity to transform any sound source into a controllable, chromatically performable 'instrument'. This capacity is responsible for the unique timbres contained within both the score and sound design of Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat. The main musical 'theme' is based on a brief vocal texture sample performed percussively to replicate the syllables which make up the words, salt, saliva, sperm and sweat. This is often embellished by an aggravating, abrasive two-note stabbing gesture, reminiscent of Bernard Herrmann's use of strings in Psycho (1960), the atonal performance of which is reflected in Brophy's electronically manipulated reworking. Breathy vocal textures sigh, gasp, pant and murmur their way into many of the music cues, sometimes ecstatic, mostly melancholic, further embellishing the sonic exploration of the body and suggesting an essentialist and unglamorous attitude to the body and basic bodily functions. A departure from this is the perverse rock anthem created from a selection of lead guitar gestures which accompanies the final credits. The anthem, titled 'I Have Seen the Future of My Guts', is built upon a percussive track formed from voice edits simulating components of a drum kit, and exhibits Brophy's willingness to experiment by intuitively throwing disparate elements together which reference hip hop, electro and rap, rather than contemporary film scoring traditions.

Several of the techniques developed by Brophy for the Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat soundtrack were further refined and exploited in a subsequent self-directed feature film called Body Melt.

Body Melt

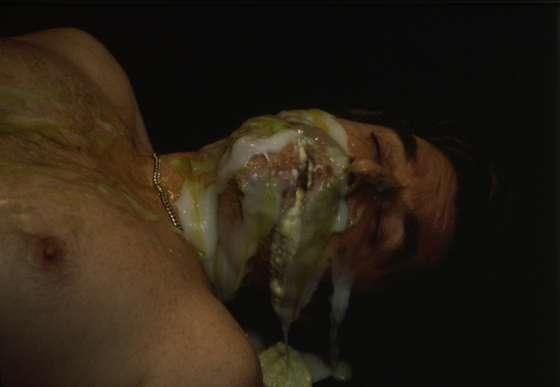

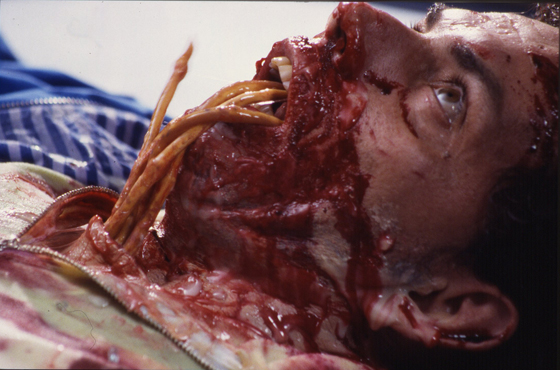

Body Melt is a horror comedy set in the outer outer suburbs of an unspecified Australian city, in a fictional location called Pebbles Court. It was funded by the AFC in 1992 and completed a year later. The Dolby stereo sound design is by Philip Brophy and Craig Carter, and is mixed by Steve Burgess. Brophy co-wrote (with Rod Bishop), directed and composed the score for the film.

Body Melt is the first and, to date, only 35mm feature film for which Brophy has developed a sound design. Body Melt's feature film length enabled Brophy to work with various elements — including a naturalistic aural environment, punctuated by stylised sound effects, and a fast-paced electronic musical score — to drive the narrative. This time span, combined with the logic, language and dynamics of the narrative film model, encouraged Brophy to redefine his aural concepts and engage in a less provocative exploration between audio and vision for the benefit of a unified cinematic experience. Hence, there is a more subtle deployment of sound, concealed behind the linear narrative development, with an infrequent dependence on the disruptive sonic gestures which inform Brophy's other scores. Individual components of the soundtrack such as dialogue, Foley, atmospheres and sound effects have presence within the aural context of Body Melt, although at times each are vividly expressed. Augmenting these components is the virtually continuous and effervescent music score, compensating for the reduction of disruptive gestures, while enabling a more balanced soundtrack to emerge in comparison to hypertextural experimental works like Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat or Maidenhead. This is not meant to imply that the Body Melt soundtrack has a less experimental, compromised role in the film. Rather the experimentation is diffused among all the aural components without strongly favouring one.

Technically, the film employs several approaches to achieve these effects, as detailed by Brophy:

"Body Melt employed an Ensoniq ASR10 [sampler] in two distinct areas: sound design and music score. The sound design uses stereo recordings by Craig Carter and myself, all of which focus on close-mike stereo textures (like onions frying, paper tearing, dry leaves crumpling, cappuccino machine frothing, eggs cracking, etc). The ASR10 was employed specifically to create dynamic spatial movement across the stereo field. The music score also uses the ASR10, but in a more conventional way. Numerous fragments of records are incorporated and processed (from Deep Purple to Dave Brubeck to Frankie Knuckles to Metallica to Bach and beyond). Once again, analogue synthesizers were heavily used to foreground a 'plastic' chemical sensation in opposition to the natural sound effects. In the final mix with Steve Burgess, attention was paid to the shifting of space and frequencies through the surround channels whenever people's bodies started mutating."

Music is a crucial element used throughout Body Melt but it does not tend to function within conventional cinematic codes. It does not define or convey psychological or motivational characteristics which enrich the characters occupying the Body Melt narrative space. It does not propose some form of subtext which encourages a multi-dimensional viewing. It does not even contribute an emotional resonance which helps nurture empathy with characters, or maintain the suspension of disbelief. The electronic score appears to have three primary functions. The first is to forcefully catapult the narrative forward by its electronic beats, bass notes and textures, and arpeggios. The second is to act as sonic wallpaper to complement the consciously banal, television soapie influenced visual design of the film. The third is to pay homage to seminal film composers including John Carpenter and Italian progressive rock band Goblin who redefined scoring traditions within the horror genre in the 1970s and 1980s, with their austere, synthesised/sequenced-based scores. 4

Body Melt's cinematography disregards the conventional look and mise en scene of cinema which engages viewers through a potent mix of seductive lighting, colour and location. Deriving its cues from banal suburban and rural locations, ugly characters, harsh light and drab colour, the score rejects the notion of incorporating a seductive arrangement of tones and 'colours', and embraces abrasive, synthetic textures which are emotionally but not thematically detached from the visual dynamics of Body Melt. The frantic tempos which punctuate the narrative, combined with an increasingly desperate, rapid cutting style, propel Body Melt with an escalating velocity to its conclusion. At the heart of this exploration of speed lies Deep Purple's song 'Highway Star', the recorded version of which does not directly appear in the film but is alluded to several times by Vince Gil and his celluloid family who are inspired by it, boisterously singing excerpts of the lyrics.

'Highway Star' seems an appropriate choice as a compositional reference. The song's driving motor rhythm that propels this suburban anthem is now electronically transplanted in Body Melt and not only performs as a structural and thematic device but also firmly reflects contemporary (popular) music's obsession with repetition, speed and rhythm. Speed in this instance is embellished by sparse synthesised timbre, arpeggiated tones, fragmented samples of acoustic instruments, truncated bass and thick-sounding bass thuds. The result is a gumbo of shifting moods and textures which has its own perverse logic and resonance, often disconnected from on-screen action. The effect is reminiscent of the structure which informs easy listening music. Dynamics seem to have been reduced, performance drained of emotional flourishes, and melodic development, 'within a cue', limited. The music cue, reduced to its bare essentials, evokes an essence of a mood, transparently conveyed with minimal embellishment. This enables the score to freely weave through the other components of the sound mix. Body Melt never languishes because of an over-orchestrated cue or a sense of self-importance. On the contrary, the music is functional: it is light, brisk, efficiently establishing mood, commenting on action, or just segueing sequences.

Body Melt is a warm homage to some of the horror film genre's most enduring icons, including Dario Argento, Wes Craven, David Cronenberg, George Romero and Larry Cohen. The narrative is a bricollage of themes which have appeared in some of these directors' work. Mutant families, body mutations and meltdowns, scientific conspiracies, visionary medicine: this mixture of themes and references to other generic work also occurs on the soundtrack, although in a more subtle form.

There is a reference to the Goblin's progressive rock score to Dawn of the Dead (1978) as the mutant zombie-like family surrounds the character Sal who is trying to escape them in a pick-up truck. There is a reference to Brad Fidel's austere electronic score for Terminator (1984) as an electronic piston-like reverberated beat is introduced to underscore scenes of the body transformation into a super being. There is a suggestion of John Carpenter in some of the cues as they peel away to spartan rhythmic arrangements, evocative of Carpenter's electronic scores for Escape from New York (1981) and Halloween 3 (1983). Even Ennio Morricone and Ry Cooder are hinted at in perverse arrangements of electronics and acoustic samples. A harmonica briefly appears to accompany the barren wastelands of outer outer suburbia, while an oddly performed guitar sample with pitch wheel manipulation emulating the slide is deployed to suggest the mature sound of white, middle-aged rock culture which enthusiastically embraces the lugubrious meandering of Ry Cooder's sound.

Certain sequences which appear in Body Melt have their visual and sonic origins in Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, making Body Melt appear at times os an expansive, reflexive version of the earlier work. The most obvious thematic connection is that of the body. A sequence shared in both films is that of the travelling microscopic close up of the intestine, accompanied by a combination of granulated rumbling, squelching noises. 5 This device recurs throughout Body Melt, representing the glandular transformations regularly occurring within the human guinea pigs, foreshadowing the climax of erupting body fluids and dislodged organs. Another associated sonic/ visual device between films is the emphasis on carbonated, frothy drinks. This theme is developed in Body Melt through the numerous hallucinogenic health satchels which have been delivered to Pebbles Court. The vigorous bubbling wash of noise which accompanies the ingestion of the fluid is sonically reminiscent of the sterile office and cafeteria sequences of Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, where strange rituals are enacted utilising soft drink cans and milk cartons. This effervescent effect is used to sonically imply health and vitality, while subverting the connotations and familiarity of the sound by anticipating the next body meltdown.

Following the completion of Body Melt, Brophy's film soundtrack work included his composition of the score for Only the Brave (directed by Ana Kokkinos, 1994 ) and sound design for Maidenhead (directed by Marie Craven, 1995 ). Both compositions were created using techniques developed for Brophy's own films.

Only the Brave

Only the Brave is a tough drama centred on the relationship between two teenage girls. It is directed by Ana Kokkinos and was co-funded by the AFC and Film Victoria in 1994. The film (59 minutes, 16mm) is in mono; the video release is in stereo. Brophy composed the score for the film.

Only the Brave is perhaps the most conventional film out of the four discussed. Its dramatic structure and narrative flow reflects a cinematic logic which is absent from Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, Body Melt, and Maidenhead. This logic establishes a range of aural expectations to underscore the conventions of the drama, which Kokkinos and Brophy occasionally subscribe to, but more often subvert. These conventions generally privilege harmonic structures over dissonance.

Only the Brave's score is an investigation of the European culture and the industrial urban location in which the film is set. The selection of tone, texture, pitch, volume and space, and how these components interact with each other and with the narrative and visual flow, invites a more detailed reading of the narrative, by offering an unusual and expansive dialogue between and within the aural and visual space. This dialogue commences in a scene in which teenage girls set trees on fire, accompanied by a mix of location sound and stylised sound effects. This brief introduction establishes a familiar structure in the way the information is presented through the characters in a logical sequence of events, though a sense of bleakness has already been firmly established by the destructive action of the girls and the accompanying evening shots of trains and industry.

Underscoring this introduction is a series of musical effects which reinforce the mischievous nature of the actions. This series also establishes a sense of textural strangeness in the aural landscape which has already been dominated by a range of abrasive industrial noises. This opening theme contains several sections. The first is a reed tone suggesting a clarinet in texture and timbre although obviously performed on a keyboard, given the unsteady, hesitating way the performance develops. The strange timing of the reed tone is quite distracting, and draws attention to the score which already sounds slightly out of place when combined with the actions and location. The reed texture hints at the apparent south European cultural background of many of the girls, where clarinet is regularly performed within traditional folk music. The reed tone is soon supported by a subtly plucked detuned backward guitar texture which has a soft rising attack and an abrupt end. This combination underscores the strangely bleak fire dance performed by one of the girls after the fire is lit. The backward guitar's pitch gradually proceeds up the harmonic scale, rising with the movements of the dance.

This guitar motif is used as an instrumental texture of rebellion signifying the delinquent nature of the protagonists' actions. The reed and guitar tones are then replaced by a harmonica-like tone, performed in a spirited fashion using a discordant cluster of notes. A sense of exhilaration reflected in the choice of tone and its performance are subverted by the introduction of dissonance, which effectively nourishes the tension already established. This also gives way to another backward guitar texture which replicates the rhythmic clatter of trains while employing the Doppler shift. The Doppler shift is perceived in natural surroundings when a moving sound passes by a listener at a stationary position and combines a stereo effect as the sound source moves from one side to another, an increase and decrease in volume, and a shift (rise and fall) in pitch. In this instance sound effects of trains, coupled with the guitar, are the source of the moving sound. The musical effect combined with the diegetic sound effects enhance the sense of exhilaration that the girls display after they flee the scene of the fire. The original reed tone is then reintroduced as the girls reflect and gaze up at the stars. But here the performance isn't as unsettling as when it is first heard. A trembling guitar sound is then introduced to underscore the girls' discussion of shooting stars. The plucked guitar tones have an upward decaying movement embellishing the dialogue between the girls. This clever musical effect then ends the scene as the camera pans past the girls onto a power station lit up like the night sky.

The unorthodox selection, combination and performance of disparate, often dissonant, tones and textures, the process of digital manipulation and treatment, detuning, and the mix of diegetic and non-diegetic textures have all combined within the first three minutes of Only the Brave to confirm that something strange, perhaps tragic, will develop over the course of the film. The tones employed within this first section effectively and economically articulate the girls' psychological, cultural and environmental milieu.

The striking effect of the opening theme is its obvious artificial replication and synthetic performance of familiar acoustic instrumentation. This approach goes against the popular trend of incorporating samples of actual acoustic instruments into film composition, a practice which has helped nurture a sense of homogeneity to the tonal structure of film music. This practice has increased with the rise in popularity of well-recorded third-party sample compact discs of orchestral and acoustic instrumentation derived from and performed in Western, Eastern and African styles. The fact that these discs are cheap and easily available has encouraged many composers to adopt them, rather than engage in the often expensive and difficult task of recording original sounds and performances.

Unusual timbres derived from the recording and manipulation of acoustic phenomenon to replicate other sounds is a compositional practice which is characteristic of Brophy's approach to sound exploration. It is based in analogue synthesis where synthesizers were initially employed by soloists to simulate acoustic instruments, particularly reeds, brass and strings. As synthesis developed, more complex programming through more sophisticated tonal generation, filtering and shaping enabled greater timbral explorations, leading to a broader and denser spectrum of sounds. Brophy engaged in these compositional explorations of analogue synthesis in the seventies with his band Tsk Tsk Tsk. He now applies the same theories to sampling, generating and shaping his own recorded sounds within the ASR10 sampling workstation. Most of the 'instruments' used for the soundtrack in Only the Brave are virtual/digital constructions of actual instruments and analogue textures. As Brophy points out:

Only the Brave employed an Ensoniq ASR10 and features samples and digital processing of electric guitars. Reconstructed samples of analogue synthesizers were employed for overlaying detuned and microtonal harmonies on the string textures. Occasional samples from records (a cello, a voice, etc. were also used and extensively reworked. One factory (preset) sample was used a clarinet — which was spatially and harmonically re-processed.

In a later scene in Only the Brave, a key, recurring plot point develops in which Alex is searching for her mother who abandoned her as a child. The mother was a singer in a 1970s rock band and a song she used to perform is employed throughout Only the Brave in several different arrangements. The song selected by Kokkinos to illustrate this plot point is an obscure number called 'Seasons of Change' originally performed by Black Feather, an Australian rock band from the period. It is first introduced as a sombre acoustic arrangement underscoring the sense of loss expressed by Alex. The second time it is used as the 'originally recorded' arrangement featuring the full band, in an emulation of the original version. As the song develops it reaches an emotional crescendo which corresponds to a visual dream sequence. At this point, though, the song is flipped backwards with the wailing lead vocals sampled, looped, and transposed up several semitones. This process effectively introduces an element of uncertainty to the imaginary quest to find the mother. Brophy isn't satisfied with allowing the song to develop, through a series of rearranged themes highlighting one of the core narrative threads of the film. The song is introduced to convey the idea of loss, and then goes through a process of deconstruction which enables Brophy to select the relevant emotional textures contained within the sound and performance of the song and construct new themes around those fragments.

The wailing lead vocals displaced from the emotional crescendo of the song have the resonance of humanness and naturalness reworked into a heavily processed vocal texture. This signifies a sense of the rock performance in its original narrative form, and enables the theme to develop. Yet the vocals also emphasize new thematic and emotional threads, such as horror, in some instances of Only the Brave by transforming the voice from a musical instrument into a hallucinogenic scream. The rhythm section of the song is rearranged and transformed into a fragmented, staccato musical effect highlighting the continual presence of trains, as well as a sense of movement, and the yearning of the girls to escape their industrial and cultural hell. The electric, taught, trembling guitar textures underscore the perpetually wired and destructive Vicki. The Rhodes piano' constructed from detuned guitar samples performed discordantly through a cluster of notes, combines with a whistle and bell to musically suggest a train crossing.

These peculiar fragments and combinations of instruments poignantly resonate with a psychological landscape which is often unstated within the visual or scripted narrative of Only the Brave. In contrast, Maidenhead employs a fragmented narrative structure and this is amplified and developed by Brophy's sound design for the film.

Maidenhead

Maidenhead is a 15-minute, 35mm experimental narrative exploration of the dreamlike journeys undertaken by a young woman. The film was funded by the AFC in 1995 and features a Dolby stereo sound design by Brophy. Craig Carter did the sound edit and also mixed the film. Brophy notes that:

"Maidenhead's sound was all edited and processed on an Ensoniq ASR10 from source stereo sound effects and atmospheres recorded by Philip Samartzis and Jennifer Sochackyj. The few musical moments in the film also employ an ASR10 for the sampling of analogue sounds and fragments of records for musical effect."

Marie Craven's Maidenhead, like Brophy's own Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, incorporates an experimental narrative structure that contains several short, at times unrelated, stories linked by the character Alice. Brophy's sound design rejects realism for stylised and abstracted environments and sound effects. Maidenhead's subjective narrative logic permitted Brophy to base his sound design on an examination of the acoustic character of the film's locations, tempered by the strange interactions occurring in the spaces: a saleswoman's persistence with giving Alice an oversized hat, or the romantic exchange between Alice's companion and a mysterious stranger on an otherwise empty bus.

These fantastic elements encouraged the use of a series of strange sound events to emphasize key visual and dramatic moments. Some memorable instances are the sound of sizzling eggs underscoring the bus moving through an arid landscape. Grainy wood creaks and slowly heaving bowling ball textures highlight 1he rickety staircase Alice descends while trying to escape her pursuer. Detuned shortwave radio crackle interfering with, or commenting upon, the peculiar logical progression of the narrative. Processed car tyre squeals recorded in underground car parks swell up to interrupt a romantic interlude. A synthetic room atmosphere perceptively rises and falls in volume as a couple engage in a peculiar, at times threatening, courting ritual. A collage of fragmented musical gestures and sound effects accompany a colourful roll of toilet paper unfurling before Alice. These strange selections of effects appear throughout Maidenhead at the most unexpected times, nurturing an abstract synchronicity between audio and vision.

The timing and duration of some of these effects is also worth noting. Maidenhead allowed Brophy to experiment with sound placement which often did not have a visual or emotional equivalent. This form of counterpoint is an important tool frequently used in music but not often in soundtrack composition, although the television series Miami Vice regularly employed counterpoint within its sound design. The nature of counterpoint as a compositional tool is one which draws attention to itself. It is a technique which is at complete odds with the transparent soundtrack approach which attempts to unify sound with image. The exploration of counterpoint in Maidenhead plays with the idea of expecta1ion and often anticipates points or actions which will be conveyed later in the narrative, Drops of water introduced in one scene fade out and reappear later in a totally unrelated place with no matching vision. A synthetic racing heartbeat bridging two sequences becomes the basis of an electronic dance 'rave' anthem for a nightclub scene. Spirited hand clapping closes one scene and then reappears in the final scene to enthusiastically conclude Maidenhead. An aggravating car horn incessantly weaves through a mix of city traffic until the otherwise pleasant urban location is unexpectedly disrupted by the aggressive actions of a Terminator-like athlete. The shortwave crackle appears unpredictably several times, briefly scrambling the soundtrack and then signing off as quickly as it appears.

These few instances highlight the lateral approach Brophy has employed within the general sound design of Maidenhead, making it an intriguing viewing experience when coupled with the subjective nature of the narrative, and the short self-contained scenes which Craven has constructed. Maidenhead reinforces Brophy's notion that aural design does not always have to follow the logic and timing conveyed by narrative and image. It certainly is rewarding when there is only a tentative relationship binding them, as it raises questions about the relationship and meaning occurring between what we see and what we hear, and whether we want to be passive or active in this engagement. Obviously there is a logic directing the development of the soundtrack in Maidenhead which is derived from a reading of the narrative, but there is also some latitude in the exploration and creation of sonic gestures and environments which do not wholly exist in, or respond to the narrative. This process encourages a more active intellectual engagement with the mechanisms involved in deciphering the links between sound and image, and the subsequent conveyance of meaning.

CONCLUSION

The soundtracks of Philip Brophy reveal an uncompromising drive to experiment on all levels of soundtrack composition. This experimentation results from a natural inquisitiveness about all aspects of film sound production, ond why those mechanisms are in place ond how they contribute to the perception of cinema. Dissatisfied with conventional applications of sound, and its poor representation within the narrative model, Brophy has incorporated contemporary music production techniques to extend the vocabulary available to him, broadening the language and experience of the films which contain his sonic explorations. These contributions have expanded the experience of the films, where the presence of sound is elevated, at times dominant, within all the interactions which inform narrative cinema. Not content with enhancing the presence of sound by explorations of volume, duration, density, timbre and space, Brophy's later works such as the Maidenhead sound design, hint at a non synchronous, abstract soundtrack which bears little relationship to the logic and structures determining the visual and dramatic components of film. This is possibly the most challenging phase in what has already been on iconoclastic film sound career. This direction suggests Brophy's rejection of a synchronous, unified realism in pursuit of the pure sound film.

ENDNOTES

1. Although initially explored by New Music composers, dissonance, counterpoint, sampling and synthesis have become the basic tools of contemporary popular music.

2. See further discussion of Spector techniques in Ribowsky (1989), of Visconti's work in Grundy 8 Tabler (1982) and of Laswell's work in Toop (1995).

3. Unless otherwise cited, all comments by Brophy are from an interview with the author (Brophy, 1996).

4. Goblin scored films by director Dario Argento such as Deep Red (1975) and Suspiria (1977).

5. All body/inner-body travelling shots are directed into the surround channels of the Dolby 4track master, so that the inner sounds are most outward and space occupying in the cinema.

6. The Rhodes piano was introduced in the 1970s but is still used by musicians who want the effect of its particular electric sound.

Listening to Colors - Sound Advice from Philip Brophy

published in Filmnews - Vol.22 No.1, Sydney © 1992

by uncredited author

The seminar on sound in film held by the Australian Film Tv and Radio School at both the Village Cinema Centre and the State Bank Theatrette in Melbourne last December managed to at least place the issue of sound analysis on the agenda for what appeared to be an otherwise rather disinterested panel of film sound technicians, film music composers and various other film culture representatives. Philip Brophy's extraordinary deconstruction of the 1988 Dennis Hopper film Colors, in terms of its rich and revolutionary use of sound, took place with little fuss. I' ve seen Philip deliver this talk three times now, and his excitement for the material cannot be questioned. Neither can his erudite and insightful observations about the relationship of the soundtrack of the film to its themes and subject matter: territory, place, location. What stuck in my mind, however, were the constant attempts by the more technically minded on the panel in the discussion which followed, to "damn with faint praise" the conclusions of the Brophy lecture — a call to recognise the dimension of high quality film sound as worthy of critique on a textual/ formal level, and to recognise the cinematic implications of the recent technical advances in film sound production by apologizing for the "real world", where deadlines and film narrative legibility are constantly the higher priorities to genuinely innovative soundtrack production.

This blithe apologia for the status quo does not help support a strategy also aimed at breaking down traditional hierarchical divisions of labour (based as they are on what amount to increasingly technically and aesthetically outmoded modes of film sound production). With the arrival of accessible digital and innovative analogue sound gathering and sound editing methods, and sound encoding and playback systems, there is no reason why Australian films should not now start to push the frontiers of cinema sound beyond their current limits. The inherent conservatism of the film industry, characterised as it is by obsequious observation of market forces, is simply not able, I suspect, to effectively alter itself in ways required to reshape the sonic cartography of Australian cinema. Innovation in any area of artistic human endeavour, as Brophy points out, is the result largely of unintentional discovery and naive experimentation with techniques and technology by definition not used by the mainstream. Little wonder then that one of the pros considered the Colors soundtrack to have been badly mixed, not fulfilling the perceived primary brief to "tell the story".

But this is precisely why Colors performs its functions with sound in so interesting a way. The film is about territory, and the signs and symbols within the onscreen complex techno/urban tribal cultures (street gangs) find reflection in the soundtrack. The 3D effect of THX surround speakers now affords the audience aural interpretations of films simply not possible prior to their introduction. As Philip Brophy outlined, areas in the auditorium are literally shaped and defined by the pastiches of sound with THX playback during Colors are allowed to commingle in elaborate textual cocktails of sonic information throughout the film. The audience is massaged by the rumbling basses of the Dolby SR stereo treatment, and startled by vivid surround effects, which, by virtue of their frequency specificity, also acoustically directly inform the psyche of the listener and influence a reading of the film quite independent of (yet not in isolation to) the 2D visual information.

Brophy made reference to the Futurists, who celebrated the mechanisms of modern life and got off on the joyride of technology. The fact that they were also neo-fascists is beside the point, they dug the experience of Teknik; automation and self. This is in a sense what Brophy himself is doing, trying to communicate the "sound bug" as he calls it: the sonic joys of a newly sonic cinema where, God forbid, the sound works better than the visuals! He talked of the difference between "planar mixing" and "dimensional mixing", the latter being an attempt to mould a 3D space out of sound rather than slavishly follow a literal sound plane adjacent to the visual screen information: e.g. when a character is on the left, the sound comes from the left stereo channel,

The recent phenomenon of spatial invasion by sound into the physical environment of the audience, with full-on frequency depth and real spatial dimension, should be welcomed by the Australian film industry, and explored for its own sake. Tactile sound, sound which exists to caress the body with its signal, is needed now in our cinema. The symbolic resonances illustrated by Brophy in Colors and made possible by Dolby SR in the sound editing and sound mixing state, have yet to be found in any Australian film, (with perhaps the exception of Mad Max 2). Where the surround speakers can baffle the audience into looking for an off screen spray can, the sound of which seems to come from above, behind and around simultaneously, to rattle and spray across the screen the title credit. Or where the sound of inhaling crack by a gang member becomes a sonic metaphor for the act of smoking in itself; the sound becomes the crack high, wafting over the audience in a stereo surround SSHHHHOOOOWWWOOOW!! Or where the ubiquity of a police siren within the auditorium echoes the socio/political function of the same siren in real life: an index of the ubiquity of the law itself; ever present, all-pervading, never leaving motherfuckers alone. The new sound technologies enable a breaking down of the naturalistic artificial boundary where totally synthesised sounds and those clearly within the logic structure of the film can happily commingle and create new sonic meaning structures.

The technoculture of Musical Instrument Digital Interface or MDI came in for a serve also. Brophy unflatteringly compared the functions of MDI to the pointing stick of the vaudeville dog trainer who triggers each of his dogs to bark a separate note to generate a song. "Cattle prod" sampling culture, he gleefully explained, really reflects the techno-careerism of white techno culture itself, hence the technical unfashionability of the source material which goes into black rap music, (old seventies blaxploitation guitar riffs, flat analogue synth bass lines, etc.) working to actively question the unspoken supremacy of techno intensive dominant Anglo-saxon ideology. Here the themes and subject matter of Colors feed back into the Brophy analysis. A microcosm of the film's soundtracks, in this case the title song by Ice-T, comes to resemble the film's soundtrack as a whole: with incidental sound effects, ambient "buzz" track, and to top it off Ice-T's own sampled (entrapped) voice being cattle prodded into saying the title "Colors, colors, colors"; all this while on the screen imprisoned gang members, some in blue, the others in red, chant and rave, themselves human "samples", taken by the white police culture, of the street life — which, to them (and presumably us) teems unfathomably outside. The real meaning of Ice-T's sampled voice has gained this extra dimension — a sonic echo of the onscreen text, especially as the sound mix of the original song has kept its various elaborate spatial orientations in the transfer and sound mix in Dolby SR.

Brophy expounds all this without batting an eyelid, yet one could almost feel the sound technicians in the audience checking their watches and rustling in their seats. I suppose chaos theory can help us here. Sound developments will reflect the interest of the filmmakers themselves who are willing to try out new approaches and challenge the existing norms. We have, as Philip outlined, become partly attuned to ways of listening, this having been defined genetically by our gradual exposure to the sound technologies we grown up with and the new range of recorded frequencies each new generation affords. The next lot of filmmakers are thus likely to display the cinematic results of constant exposure to MDI, THX, Dolby SR, and the steady boom of the Roland TR808 drum machine.