Reviews

Body Melt

published in Cinema Papers No.102, Melbourne © 1994

by Rafaelle Caputo

Body Melt is comprised of a number of sub-plots, one of which has the characters Sal Ciccone {Nick Polites) and Gino Argento (Maurie Annese), a couple of Italian kids with loads of sperm backed all the way up into into their brain, They start off on a jouney to Vimuville, a health farm-curn-leisure resort, where they're anticipating a saucy weekend. They never make it; instead, when the Monaro's windscreen is damaged, Sal and Gino are forced to seek aid from a homicidal backwater family that's headed by Pud (Vincent Gil), who runs a kind of roadside service.

But before the pair encounter their grisly demise, the boys are half-affected (-infected) by the reckless antics of this family. In one telling moment, Sal and Gino look on with both excitement and disbelief as two of the family's screwiest members fell one of Australia's sacred emblems (a kangaroo) with an expertly flung rock, then cut out its andrenal gland and swallow the gland to the tune of tantalizing moans.

Any sense of cultural and moral indignation (which amounts to the same thing in this case) over this scene is intentional. Yet, this is not indignation for its own sake. For while Body Melt knows itself to be something of an illegimate child of this thing called Australian film, it is also like a child looking to adopt (or create) its own family. The kangaroo scene is one of the sharpest emphases for the film's place on the cultural landscape — the Australian outback is one to be reconstituted as Texas Chainsaw territory.

Director Philip Brophy is not one to avoid the reconstitution of all sorts of cultural icons, objects, shapes and forms as a formal practice. It has informed his work across a range of media, music, performance, television, video, publications and, of course, film. For the readers of Cinema Papers, Brophy's earlier 60 minute featurette, Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat is a good example. The film is composed of four segments, each segment telling the same minimal story, yet each story constituted in four different ways — through food, sex, swearing and violence.

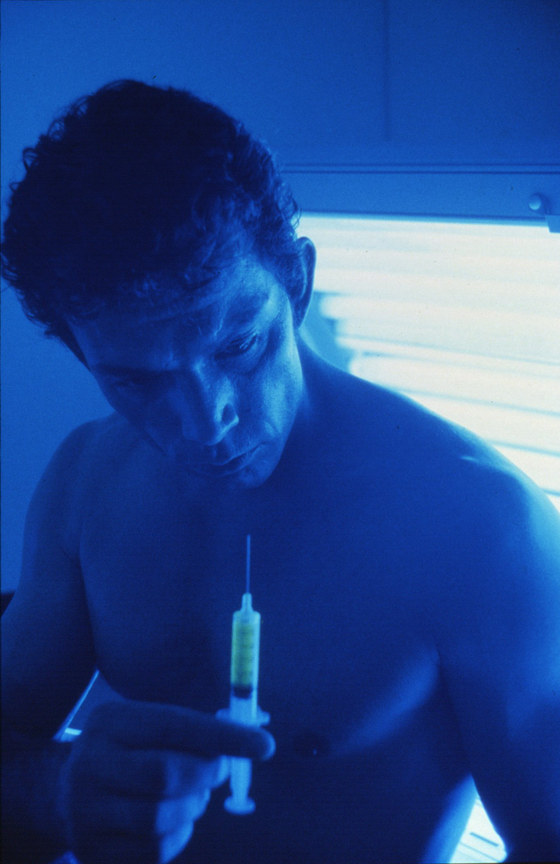

Similarly, Body Melt involves the occupants of four sickly pristine suburban homes located in Pebbles Court, Homesville — a newly established, A.V. Jennings-like estate. This time, however, the stories are interwoven by the thread of the Vimuville organization which has chosen the unsuspecting occupants of Pebbles Court for experimentation of a new body enhancement drug. But the drug is defective, and their bodies become prone to uncontrollable fits of ripping apart, throwing up and melting down.

It becomes fairly clear that what happens to each set of occupants corresponds to cross-sections of the horror movie: the backwater psychosis plot; supernatural-occult plot; the conspiracy-parasite-contamination plot; and so on. The film is a part-typology of horror plots, but Body Melt does not go about its work as a simple typology, for while the representation of suburbia is not a stranger to horror, Homesville is not any suburban estate. It is the suburbia of Australian television land. What is not lost on the audience is that most of the film's characters are very familiar sorts — they stem from the box in the corner and run the gamut of television from soapies like Neighbours, through cop shows like Division 4 or Cop Shop, on to comercials for young home buyers, fitness freaks, FM radio, you name it!

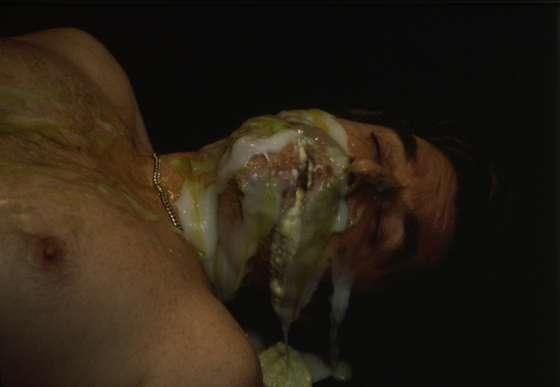

Again, it is a question of reconstituting the representation of Australian suburbia as a nightmare. And it is the body, of course, which is the focal point of reconstitution. In other words, it is not insignificant that most of the characters end up becoming the very fears they try to stave off, or the desires they wish to fulfil ("death by hyperreal causes"). For example, an over-sexed body builder at Vimuville grows an unnaturally big erection to the point that it explodes; the health and fitness fanatic, Thompson Noble (Adrian WrIgt~t), becomes a blubber of snot; Vimuville's beautiful and youthful hostess, Shaan (Regina Gaigalas), shrivels up into an old hag and then becomes a mass of flesh tissue.

Another aspect not lost on the audience is that Body Melt definitely loves its backwater family; whereas mostly everybody and everything else in the film is ready for a lampooning (both a literal and abstract lampooning). The cause of the mayhem is, after all, as a result of Pud's sneaking off with an essential ingredient to the body enhancement drug some twenty-odd years ago. This is important because, if the film is a part-typology of horror, then it's also dealing with the (difficult) question of origin. When Sal and Gino chance upon Pud and his clan, again it is not insignificant that a good deal of the dialogue is devoted to talk about where people come from. At one point, Pud asks Gino where he is from; at another, one of Pud's off-spring (?) asks Sal. But, more importantly, as a reflection of where Body Melt is coming from, is a response Gino gets to the question of whether Pud is the clan's father: "Ah, dunno, We' re all kinda mixed up."

To sum up, the practice of reconstitution in Body Melt is in part a dynamic response to the phenomenon of the Australian film industry (which could do with a little reconstitution): "We' re talking fuckin' nineties, man. Cognition enhancers - designed to take you into new intra-phenomenological dimensions ... whooshl" The other essential part of reconstitution is that it makes for a helluva laugh. What other Australian film could get away with a line like, "You fuckin' Bob Geldof of the gum-set!"

Strange Things

published in Photofile No.44, Sydney © 1995

by Adrian Martin

Philip Brophy's Body Melt is a catastrophe narrative. One sunny day in suburbia, a hideously dying man crashes his car into Pebbles Court, Homesville. He's been brought to the point of meltdown by an experimental drug marketed as "Vimuville" vitamins, and he' s arrived too late to warn the Court's inhabitants not to swallow the sample dropped in their mailboxes. So then the story scatters: a businessman (William Mclnnes), beset by increasing hallucinations, picks up a strange woman at the airport and takes her home; two rowdy teenagers (Nick Polites and Maurie Annese) get waylaid at a run-down farm of a seemingly "inbred" family; a yuppie family journeys to a sinister health resort; an expectant woman (Lisa McCune) at home begins to feel mighty queasy.

It's an important aspect of the headlong momentum of the film that the scattered lines of its narrative catastrophe become a bit blurred and elliptical. The teens, for instance, are left at the scary high-point of their tale — circling madly, with their predators moving in for the kill. The pregnant woman' s husband (Brett Climo) is taken away by the police at a point in the film where you instinctively decide to forget all about him until he explodes like a time bomb at the cop shop, providing a big finale. This pervasive sense of a terrifying and magical 'narrative space' that gets away from you, that is littered with booby traps, forgotten possibilities and surprises is crucial to Body Melt as it is to contemporary horror-fantasy cinema generally.

A certain, precise fantasia about space and topography, and the way that people perceive these realms, informs every stylistic level of Brophy's film. Early on, a shot sweeps us around the entirety of Pebble's Court, closing in on and then getting absorbed by the black interior of a letter box. Spaces and places, like the narrative with its off-shooting lines, constrict and then explode. Vimuville hastens these hallucinations, which the film humorously refers to as "mind enhanced" and "intra-phenomenological". And Brophy's sound design (the most aesthetically sophisticated sound work being Jone in this country today) recreates this whole fantasia, powerfully reinforces it, on the aural plane — soundscapes that blur the distinction between strictly musical accompaniment and a fictive swirl of burning, breathing, pulsing, stiring, melting, ringing action sensations, soundscapes that swallow the ambient noises of a space (like an airport) and transform them into chambers of deranged subjective experience.

Brophy is one of those practitioners of the film fantastique — like George Romero or Larry Cohen — fond of a certain form of allegory which is specific to popular art. This is not the stately, schematic, 'architectonic' allegory ot Peter Greenaway, but it has a similarly determin ing, almost didactic force. Narrative situations provide a kind of prism whereby a series of variations on a central premise are illustrated, demonstrated, explored, contradicted, synthesised. In the popular-allegorical mode, characters are conceived of as various bundles of traits, tics and appearances that are exemplary in relation to film's chosen field of inquiry. In Brophy's work, pop-allegory meets the speculative ruminations of the 'essay-film'.

Brophy's key subject for some years now has been the body, and bodily experience: life seized as a calculus of bodily 'effects', stimuli, drives, mechanisms. Horror cinema offers an expressionist statement of what is for him, a kind of base, physical reality — bodies that devour and_'decay, consume and expel, peel and ravage. The film's dialogue reminds us (in its popallegorical mode) of such daily realities: a baby inside its mother is "the ultimate parasite"; everyone's hooked on some kind of drug. At one level, this is not far from Greenaway's remark (apropos The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover): "I concern myself with people as being a body, an object a bulk, a form, a shape, something that throws light, makes the floorboards creak, indicates volume".

But although Brophy shares some of the strategically cold solipsism and brutal bodily 'materialism' of Greenaway, there is in fact a rather more lively and engaging model of character, characterisation and perfonnance evident in Body Melt. This doubtless comes in part from Brophy's vigorous work with actors (such as Gerard Kennedy) who clearly have no qualms about throwing around their bulk, altering their voice tone or contorting their facial features for an appropriate visceral or generic effect.

The people in Body Melt are at once extreme 'primal' apparitions — exploding wombs, cataclysmic orgasms, stressed-out, derailed express-trains of mind, skin and hyper-simulated desire — and also the height of acculturation', wearing, absorbing and reflecting every consumer fad that shapes everyday behaviour, from heavy metal music and skate-board riding to aerobics and New Age diets. As well, each person has their own distinctive nuttiness and, inevitably, they form extended, unpredictable, macro-rhizomes with neighbouring bodies.

The phenomenon of family — with all its impossible, inbuilt ties, binds, symmetries, attractions and repulsions — is for Brophy something like the ultimate mystery or puzzle, indivisibly social and human, natural and cultural. Body Melt 'worries' on the paradoxes of the family mystery in a memorable fashion — especially in the immortal moment when Bud (Vince Gil) reflects on his own far-gone mutant clan: "Families sure are ... strange things".

Body Melt

transcript from SBS Movie Show episode No.34, October 26th, Sydney © 2003

by Quentin Tarantino

“I’m a huge fan of Australian cinema. I see the ones that come out – but I have to say, that things are changing. But see, I think that the time I love the most for Australian cinema was the very late 70s and that brief time in the 80s, because to truly have a living breathing vital film industry, you can’t just make art films. It can’t just be auteur-driven work. You need exploitation movies. You need genre movies. You’re making a few now, but there was an explosion of them back then. And for me, I remember the exploitation films as much as THE GETTING OF WISDOM or BREAKER MORANT. You need the balance of both of them. And at the premiere (of KILL BILL Vol.1) I was proud to give a shout to Brian Trenchard Smith, who I think is a terrific exploitation craftsman. I loved DEAD END DRIVE-IN. I thought it was a terrific movie. And really, the Australian film of the 90s that had the most vim and vigour in it was Philip Brophy’s BODY MELT. I really put that – and this is a big compliment – right alongside Stuart Gordon’s RE-ANIMATOR, as one of the best movies of its type – a cool, sexy, gory, funny horror film.”

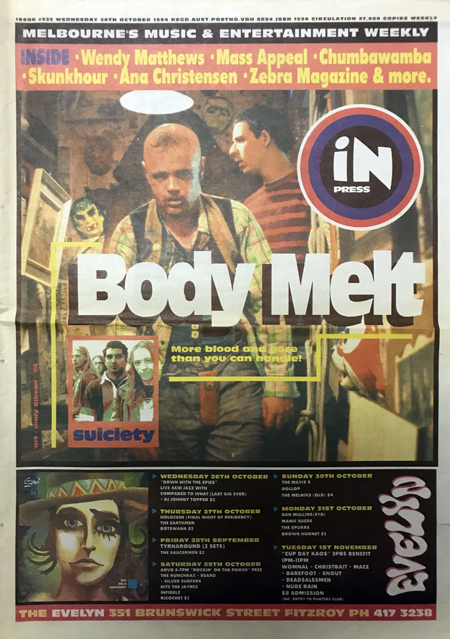

Body Melt: Then and Now

published in Film Alert 101 February 22nd, Melbourne © 2017

by Adrian Martin

It must be strange for filmmakers to experience all the hopes, expectations and agonies that accompany the making and release of any movie that, in its day, ‘does not perform’ at the box office, and then slips into an awful, twilight oblivion … only to then find that same movie, 20 or 30 years later (that is, if they are still lucky enough to be alive), recycled or even restored as some kind of ‘cult classic’.

I’m not sure if Philip Brophy’s Body Melt (1993) yet constitutes a cult classic, but it should. I vividly recall (as a friend of the director and many others involved in its production) all the thought and energy that went into its making, and the tremendous vibe at the Melbourne Film Festival premiere. I remember being on a Radio National panel discussion that same month, declaring Body Melt to be (as was subsequently quoted in publicity) “the best Australian film of the year!” – and being scoffed at by a few rather conventional industry-types on that panel (no names). And I can still see the expression on Philip’s face when he told me, some time down the track, that – various international sales and screenings aside – the film just seemed to vanish after that MIFF premiere, especially within Australia itself.

Maybe 1993 wasn’t the right time for Body Melt, which I happen to enjoy as much now as I did 24 years ago. But how can anybody ever know what the right time is, or will be? What the most propitious cultural conditions are? As Philip himself might say: you make what you make, what you are compelled to produce and what you can manage to produce, and you put it out there. The rest is history.

So let’s talk history: then and now. Australian film culture is different – a little bit different – in 2017, compared to the early ‘90s. Today there is some muscle behind the campaign to make genre films – especially horror films – in this country. After all, there are worldwide (albeit unexpected) successes to prove the case, like Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook (2014). And there’s a tremendous groundswell of activity and goodwill associated with an event such as Tasmania’s wonderful Stranger With My Face festival, encouraging women to take up the fantasy-horror-thriller genres with a righteous vengeance.

This pro-genre campaign, in fact, started a long way back: in the 1980s, at least, as I remember it. Philip Brophy was one of the first voices in the pack, long before the miserable Melbourne Underground Film Festival with its proto-fascist bleatings, and intriguing one-offs that drew some attention like Sean Byrne’s The Loved Ones (2009). You only have to hear the enthusiastic support that Body Melt cast members including Vince Gil express for the project in the ‘making of’ bonus features from the time, included in Umbrella’s superb new Blu-ray release of the film: against Australia’s own dire ‘tradition of good-taste quality’, here was a movie connecting not only with the most vital trends elsewhere (the 1980s had been the great horror years of George Romero, David Cronenberg, John Carpenter, Larry Cohen …), but also that suppressed Aussie tradition represented by the Mad Max films and many other culturally disreputable items – the tradition that (at least back then) seemed always to be gingerly erased from the official histories of our national cinema, or treated at arms length (if acknowledged at all) by mainstream, middlebrow critics of the Neil Jillett/Keith Connolly/Evan Williams ilk. These actors on the Blu-ray say it well, and not just because they feel they are obliged to: Body Melt will be a rude but necessary shock, the start of a new era in Australian cinema, a confrontation with all kinds of taboos reigning over subject-matter and film style …

Some things change, and some things don’t; or, at least, some things take far longer to change. When I think back today about the fact – the miracle, almost – that Body Melt really happened in 1993 and made it at least to the MIFF screen (and, subsequently, to many VHS and DVD shelves around the globe), I imagine what it must have been like to ‘pitch’ this project, to justify and explain it, to funding bodies such as Film Victoria and the then-named Australian Film Commission. In fact, we don’t need to imagine it: the Umbrella Blu-ray contains many priceless preparatory documents of this sort, raking over the budget (which is, of course, a tiny fraction of what Scorsese gets to spend on a ‘small’ project like Silence), the screenplay structure, the casting … (This type of ‘extra’ is a godsend to any serious student of Australian cinema.)

I had worked closely with Philip on projects such as the DIY publication Stuffing: Film: Genre (1987), and analytically pored over many of the same, inspiring film-texts (everything from Dario Argento’s Suspiria to the avant-garde fictions of Alain Robbe-Grillet) in classrooms and elsewhere, so I think I know what Body Melt is centrally about: it’s a film about “the body”, the human body in all its states, but particularly within the new world of the ‘90s – an age of designer drugs, burgeoning health-and-lifestyle TV formats, and queasily free-floating sexualities – and especially all that as refracted in pre-fab Australian outer-suburbia.

But let’s just stick, for the sake of our historical comparison, with the body. In the early 1990s, the statement “this film is about the human body” would not have made much sense to almost any bureaucrat in a government-funded film office. It still may not make much sense to them now. Funded projects usually glide along rollers that are greased with familiar, humanist, Manchester by the Sea-style formulations like: this is a film about adolescent coming-of-age; or the separation and reconciliation of a longstanding couple; or a family reunion at Christmas. Even today, movies like The Babadook, genre-trappings and all, are given this kind of reassuring, psychologistic gloss: it’s a film about a woman overcoming grief, facing her fears …

Philip Brophy’s sensibility – and I think this is true from the first manifesto I read of his from around 1977 – starts from a completely different baseline premise: on the one hand, there’s the rich materiality of a medium like music or film, its images and sounds, and all the sensations they can prompt in us; and, on the other hand, there’s the murky pool of real-life culture in which these objects swim – as well as the ideas we can grab to formulate how this culture works, where it’s come from and where it’s going. So, there’s a concrete side and an abstract side to Body Melt – but nothing in that realistic-plot-and-character middle-ground which mainly defines Australian film (and indeed, most ordinary films everywhere).

There are two separate audio commentary tracks on this edition of Body Melt. The first is a three-hander featuring Philip, Rod Bishop (co-writer/co-producer) and Daniel Scharf (co-producer); it offers a valuable recollection of the production process. The second commentary is Philip alone discussing matters of the soundtrack: its composition (for the music score), its construction (and technical reconstruction in 2016, no easy task given all the intervening changes in technology), and its mix. This track is packed with analytical insight into many kinds of filmmaking issues. Along the way, Philip makes clear his approach to characterisation as a matter of “ciphers and stereotypes”; he explains why he refuses to write conventional music ‘cues’, or to underline the scripted feelings in a scene (putting him at odds with all current, ersatz, industry wisdom about how music is supposed to “emotionally involve” you in character interactions and situations that are pretty darn obvious, anyhow); and he illuminates the process of his arriving, at last, at his preferred, initially envisaged mix, scraping away the typical ‘softening’ and conventionalising techniques in order to arrive at a “visceral, physical” experience of the senses for the spectator’s ears.

One label that Body Melt could not quite shake in 1993 – and probably, in truth, did not entirely wish to shake – is “trash”. As Philip explains in one of the making-of bonuses, if someone is not into horror cinema, and never watches it, then that cinema is liable to be always the same thing to them; and, most likely, they will assume it to be always, one-dimensionally, disgusting, vulgar and trashy. Horror aficionados, on the other hand, know that the genre runs a wide gamut from sophistication to (non-pejoratively) trash. Body Melt absorbs many aspects from across this horror spectrum. It is at once a fine-grained, intellectual essay-film, and a gleefully childlike, sensational exploitation of every anti-social and anti-human thing a movie can imaginably show.

And I can’t think of too many other Australian films which could fit that description, then or now.

Body Melt

published in Herald Sun October 28th, Melbourne © 1994

by Leigh Paatsch

As far as franchised health farms go, you would be well advised to avoid the wares of a company known as Vimuville. Located in the countryside just north of Melbourne, they've had a spot of trouble lately perfecting the formula of one of their most popular powdered tonic drink lines.

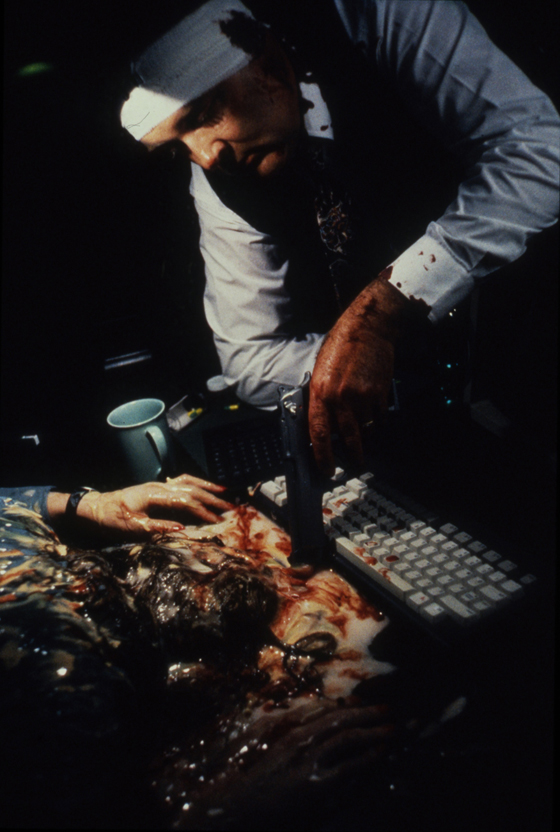

It seems that a mad doctor named Carrera (lan Smith) has let his desire to experiment get slightly out of hand, and as a result, most Vimuville customers have taken to melting within the skin of their own bodies .... A sad case, indeed. Sadder still for the inhabitants of Pebbles Court, Homesville, ~who seem to be dropping like flies afler hopping into a few free sachets of Vimuville products. It's up to Detective Sam Phillips (Gerard Kennedy) and his intellectually challenged sidekick Johnno (Andrew Daddo) to investigate, and the horrific tale of subterfuge in the name of science that they uncover is a tacked-out horror to behold.

There's a lot to like about local director Philip Brophy's feature debut, not the least being that he has injected a necessarily slender storyline (to accommodate some brilliantly bilious SFX and a subtly satirical production design courtesy of Maria Kozic) with a cavalcade of entertaining cameos by TV soapstars past and present. On another level, however, Body Melt seems very eager to explore and expose the macabre mediocrity of Australian suburban life - and while it sometimes lacks the momentum to always hit its targets, Brophy's bravado is to be admired, given the deceptively broad amount of territory covered in Body Melt. There is an energy and enthusiasm (not to mention a healthy disrespect for flaccid filmmaking conventions) at work here that is sorely lacking in most Australian productions, recent competition included. Deserving of a far wider audience than its lateshow-only release may uncover.

In appreciation of Oz gross-out social satire Body Melt

published on SBS movie blogs October, Sydney © 2016

by Ian Barr

Like many Australians of a certain age, my first memories of Philip Brophy’s infamous 1993 horror-comedy are related to it’s memorably bizarre VHS cover, which I saw repeatedly when I experienced horror films mostly as reveries inspired by browsing their cover artwork at the local video store. This one – likely designed with little fuss – depicts a giant, gorily detached eyeball hovering above a row of perfectly matching suburban houses. A cast list appears at the bottom, including some relatively big names from Aussie TV (Lisa McCune, Andrew Daddo, Ian Smith), whose faces are curiously absent from the cover itself. At the very top, the film’s tagline appears: “the first phase is glandular… the second phase is hallucinogenic… the third phase is…” Then the title below – each word emblazoned in garish orange and blue typefaces, respectively – completes the sentence.

This image of a depopulated, soulless suburban landscape beneath a giant, eviscerated eye – positioned like some disgusting panopticon – was at once queasy, apocalyptic and threatening, and, as I would learn a few years later upon finally seeing the film itself, entirely apropos. Body Melt’s main setting is the fictional Pebbles Court, Homesville; a sterile gated community located in a cul-de-sac street somewhere outside of Melbourne, and introduced with a smooth tracking shot that makes the area look computer-generated. The residents are soon to be the guinea pigs of the new dietary supplement pill “Vimuville” (revealed in one of the film’s funniest gags as an acronym for “VIsceral MUscular VItalization of Latent Libidinal Energy”), delivered to their mailboxes from a shady pharmaceutical company of the same name, and which turns out to have gruesome side effects. The exceptions to the intake of this drug include two young men, who, in a Hills Have Eyes-like sub-plot, end up taking a horny road trip before becoming prey for a inbred rural family.

The latter digression initially feels unnecessarily elongated, but eventually reveals itself as a great shaggy-dog joke: positing that whatever nightmares Australian suburbanites can conjure about the ‘uncivilised’ outback are nothing on the horror of their own mediocre, aspirational, health-and-fitness-obsessed, bourgeois lifestyles. Without a main character, and only a barebones plot, Body Melt finally becomes a free-floating exercise in spectacularly gross makeup effects, subjecting its variety of caricatures (from expectant mums to helium-voiced bodybuilders to drug company nutjobs) to an assortment of fatal mutations, in which bodily organs revolt against their abusers (tongues swell to anaconda-size, penises explodes, placenta kills a soon-to-be father). As a piece of social commentary, it’s never particularly nuanced, but its gut-level, punk revulsion toward consumer culture is always matched by it’s artfully manic incoherence.

Indeed, Brophy (who as early as 18 was a member of the Melbourne avant-garde music group known as → ↑ → and who’s straddled art and academia since) actively and pointedly rejects demands of tidy storytelling or characters to identify with. His previous film was the experimental mini-feature Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat (1988), which presented a few days in the life of a corporate drone, accentuating all the metabolic detail of his daily routine – through expressionist camerawork and sound design – to the point of surrealism. Body Melt is as much of an expansion on that film as it is a successor of Peter Jackson’s early splatter-comedies like Bad Taste (1987) and Braindead (1992), albeit more hostile in tone than Jackson's relatively childlike work. The influences of Body Melt are broad-ranging – J.G. Ballard, Jean-Luc Godard, DEVO, Ozploitation, as well as informercials, TV soaps, porn, and music videos – befitting Brophy’s multi-disciplinary background. The manner it combines these reference points is graceless by design; the whole film feels like it’s been assembled by a frustrated viewer’s channel-surfing, adding up to a work that’s against everything including itself (the infectious techno theme composed by Brophy himself, includes a sample of the words “healthy, wealthy, wise”, turning the title of the Channel 10 staple into a sneering, sinister mantra.)

The most prominent template for Body Melt’s premise is David Cronenberg’s 1975 debut feature Shivers, in which the repressed, middle-class tenants of an anonymous high rise building become the victims of a mysterious sex-epidemic. Both films are equally unpolished and inventive, but while Shivers established Cronenberg as an exciting new talent, and laid the path for his long, diverse career in feature filmmaking, the reception to Body Melt killed any chance of Brophy making the same impact. “Ten years ago, I thought it would be really fun to get then-Coles girl (Lisa McCune) to drop her placenta one month prior to child birth, then have the placenta force it's way down her husband's (Brett Climo) throat while her womb explodes”, wrote Brophy, reflecting on the film in a 2004 piece titled ‘My Dreadful Failure as an Australian Filmmaker’, which echoes the caustic, despairing humour of the film itself. “I also thought it would be a barrel of monkeys to kill a whole lot of soapie stars in a feature film. I also thought people would like it. Here in Australia, they sure didn't.”

Even with little surviving evidence of its general critical and commercial failure, it’s not hard to see why – Body Melt is as nihilistic as horror-comedies get, sledgehammer-subtle as a satire, with a narrative that’s desultory and nonsensical even by the standards of the genre. And yet, as a gleeful decimation of Australia’s middle class, it has a rare gusto that has lost none of its bloody and snotty power.

Body Melt

published in Eye For Film April 11th, London © 2009

by Jamie Kermode

"The first phase is hallucinogenic. The second phase is glandular. The third phase is... aaargh!"

The earnest whistle-blower racing to the rescue at the start of this film doesn't get to finish his sentence because he's already been spiked with the experimental drug in question, and when the third phase begins he experiences total body melt. Naturally, this interferes a bit with his driving. Before the detectives arrive on the scene the tentacles have retreated back into his mouth and he looks like a run-of-the-mill crash fatality, but at least he has succeeded in leading them to Pebble Court, where they soon begin to suspect that something dodgy is going on. The residents of this quiet Melbourne suburb know nothing, but they are the subject of experiments by a sinister group of scientists seeking to extend the powers of the human body. Body melt is an unfortunate side effect. The more unfortunate because the whistle-blower will not be its only victim.

It's a crying shame that soulless films like Scream and Scary Movie get so much attention whilst this far more astute and entertaining horror spoof has languished on direct-to-DVD. The trouble is that, by doing his thing so well, director Philip Brophy has left audiences unsure if his film is a spoof - but you only have to pay attention to its innovative camerawork, perfectly arranged lighting and seamless continuity to realise that there's a lot of talent behind it. Whilst it would be entertaining either way, it's clearly more than just a halfhearted slice of exploitation movie-making - it's a hilarious tribute to the best-loved cliches of the genre, and the affection and understanding that have gone into it mean it has real spirit, energy and character.

Every Aussie exploitation success is referenced here. You'll see inbred hick mutants, crazed scientists, dangerous naked women, faces bursting open, a deadly pregnancy, weird drug experiences, squeaky-voiced bodybuilders, bizarre kangaroo antics and buckets and buckets of animate snot. What's even more entertaining, at least for Australians, is that you'll see it affect a cast made up mostly of popular soap opera stars like Ian Smith (Harold from Neighbours). UK readers might want to imagine TV's Richard and Judy melting live on air to get an idea of how much fun this is.

Body Melt is not a film for those who prefer to take their horror seriously, but if you like gore and grotesquerie with a great sense of humour, it's a real treat.

Body Melt

published on Oh, The Horror November 11th, USA © 2012

by Brett Gallman

Body Melt’s title rightfully alerts you to its implicit body horror, but it may conceal that it’s a bit of a mind-melter too. Unfolding in a twisty, almost opaque manner, it offers a skewering glimpse at the fallout of 80s excess by taking aim at the “clean living” movement that was farmed out to pharmaceutical companies in Australia (and beyond). Phillip Brophy (who sadly never directed a film after this unhinged debut) delivers a cock-eyed, irreverent, and gruesome take on a suburban culture rotting from the contents of its mailboxes and medicine cabinets. The picturesque enclave of Pebbles Court is home to a typical array of suburbanites: a young couple, an ideal family of four, etc. One day, one of its inhabitants comes careening down the block in his car, his body having been sieged by some malicious force that ends up splattering him all over the pavement. Unbeknownst to him and his fellow exurbanites, a local health club has made them the unwitting guinea pigs for Vimuville, a vitamin supplement meant to result in a perfect human specimen.

Unfortunately, it’s only good for destroying the human body in the most outlandish and agonizing manner possible, a fact that’s made clear as the film follows a menagerie of characters as they crumble under the influence of the drug. The format almost gives Body Melt an omnibus feel, as the various characters rarely come into contact with each other, save for the pair of cops who are quick to follow the evidence trail that enables them to unravel the conspiracy. Apparently, the film’s script was cobbled from a few different short story ideas that Brophy had kicking around, and it often shows. There’s a real scatterbrained quality that makes it difficult to grasp its tenor, at least at first; Brophy’s pacing is sometimes lethargic and dwells on certain subplots at the expense of others, so it takes a for the faux-anthology format to take hold.

Oddly enough, by the time it does settle in, it really doesn’t seem to matter because the film has found a unity in its tone, which melds the satire of early Cronenberg with the splatstick approach of early Peter Jackson (whose genes descend from Sam Raimi). Brophy’s manic impulse for the grand guignol is revealed almost instantly when his first victim slowly deteriorates before our eyes, and the slick but smart gags enumerate from there. Nearly every character’s body rebels against itself, whether it’s a pregnant woman’s placenta or a guy’s cock, a conceit that underlies Brophy’s simplistic but pointed irony that our bodies will fail us regardless of our attempts to stall it. Not only that, but they do so in spectacular, over-the-top fashion as Brophy puts 80s consumerism in the crosshairs before delivering a savage but amusing beat down. The wit is one sharply crafted note that doesn’t arrive without some clever visual wit; for example, a victim’s fate is foreshadowed when liquid pours over his face on a photo ID.

Visually, the film continues to unify itself by cobbling together its various modes into something that roughly replicates channel surfing. Domestic scenes are shot and staged like commercials or sitcoms and are laced with a candy-colored coating that sweetens the eventual destruction; mean, an episode featuring a couple of dimwits who encounter a family of mutant cannibals (how many times has that setup been cannibalized itself) recalls dusty, rough and tumble Ozploitation roots, and the clan’s rotting abode is a refuse of pop culture signification that’s been left to decay along with its inhabitants. Still other modes abound; episodes centered around a man haunted by a past lover is perhaps the most traditionally horrific, the detectives’ paper trail takes on the form of a procedural drama. Body Melt is certainly scatterbrained, but it’s arguable that Brophy is also taking the piss out of how we’re forced to process media at a rapid clip that dilutes our attention spans.

Brophy’s ambivalence towards it all highlights the droll ferocity of Body Melt. Few characters (if any) are sympathetic, leaving viewers to delight in their gory demises. If the slasher cycle of the 80s offered some sort of bizarre, unwitting catharsis for droves of “Me Generation” viewers who indulged in their own destruction , then this film takes one step beyond that by poking fun at the neon-clad 80s afterbirth. The drugs are now prescribed, the sex now codified beyond teenage lust, but the splattery results are just the same. Body Melt’s humor sometimes goes very black, as no one, including the idyllic family of four, is spared from Brophy’s satirical bite. While he’s content to hammer on one note--the film doesn’t go much further than delighting in the literal melting and decay of this culture--Brophy incisively mixes camp, gore, and wit to realize one of the more oddball splatstick entries from the 90s.

I’m not sure why this represented Brophy’s lone directorial effort (he’s since reemerged as a composer for a handful of films). Body Melt feels like the work of an assured director that manages to take an amoebic script and meld it into something that’s solid but still drips around the edges. Not surprisingly, the group behind the special effects went on to have nice careers (you still see some of these guys’ names popping up in big budget films today), as their work here is sort of the calling card for Body Melt, though it’s at least underpinned by some sort of commentary, however unsubtle it may be. The film was released on DVD once by Vanguard, and the disc boasts a director’s cut that looks nice and lush thanks to a restored transfer. There are no special features to be found, but it’s a release worth owning since Body Melt is a colorful, scrappy, and rugged Ozploitation flick that’s got brains to spare--which is probably why so many of them end up getting splattered all over the place.

Body Melt

published on Blu-Ray Review September 21st, USA © 2018

by Brian Orndorf

1993's "Body Melt" is one of Australia's rare forays into gross-out territory during the decade, with co-writer/director Philip Brophy aiming to generate is own swirling brew of liquefied body parts, social commentary, and regional extremity. Brophy's backed by quite a varied cast and a solid team of energized tech departments, aiming to make the feature appropriately disgusting and slick for a B-movie, with the effort retaining all sorts of disgusting visuals while maintaining a professional edge, missing the questionable grunginess this type of entertainment usually provides. "Body Melt" isn't big on story or connective tissue between subplots, but it does maintain menace, often the cheeky sort, giving the viewer exactly what the title promises, tricked out some with a defined Aussie sensibility.

The Vimuville Corporation is dedicated to the evolution of human development, distributing a new line of vitamins able to help the Average Joe achieve their best after ingesting pills and powders. A test market is found in Homesville, outside of Melbourne, finding executive Shaan (Regina Gaigalas) sending free samples to the locals, with Bronto (Matthew Newton) hoping to enjoy the benefits of the mystery substance. All hell breaks loose when a rogue Vimuville scientist dies while trying to warn others of deadly side effects, but the loss is too late, with bodily changes beginning to spread around the housing development. With citizens losing their minds before losing their skin, Detective Phillips (Gerard Kennedy) is brought in to investigate, baffled by what he's finding. And in the outback, a critical clue to Vimuville's origins is found with Pud (Vincent Gill) and his family of mutants, who offer hospitality for two Homesville residents, teens Gino (Maurie Annese) and Sal (Nicholas Politis), who make the mistake of stopping for a bite during a road trip.

Originally envisioned as an anthology film, "Body Melt" retains distance between subplots. Brophy takes on one set of characters at a time, failing to braid together a cohesive display of suburban panic, instead dishing up horrors one spoonful at a time. It's not the most dramatically involving feature, with a nagging disconnect between characters as the hunt for Vimuville's modus operandi continues. "Body Melt" isn't gripping, but it's visually arresting, following the path of the vitamins as they claim victims through phases of psychological and corporeal domination, with Bronto the most defined of the chosen few, tracking his symptoms, which including hallucinations featuring a demonic woman who volleys between terror and seduction, after a unique prize from the woozy man to add to her special collection of body parts.

There are inspired detours along the way, including the outback encounter with Pud and his clan of corrupted human beings. Just why they are who they are is the mystery of "Body Melt," but Brophy has fun with the segment, which takes on a "Texas Chain Saw Massacre" level of craziness, especially with the "kids," who enjoy killing kangaroos and feasting on adrenal glands, which, in the grand scheme of things, is a fairly tame sight for Sal and Gino, who are forced to fight for their lives. Brophy even manages to juggle potentially distasteful additions, with Vimuville aiming to test their goods on a pregnant woman, which results in the creation of a killer placenta, adding a wily villain to a collection of fleshy horrors.