Reviews

100 Anime

published in Screening The Past No.20, Melbourne © 2006

by Susan Napier

Anyone familiar with Philip Brophy's fascinating work on Body Horror will not be surprised by how he approaches Japanese animation in 100 Anime. Brophy's book is emphatically not a paint by numbers introduction to anime (or a "tourist guide book", as he dismissively describes such works). Readers will not find a history of how Japanese animation came into being, nor will they find even a single discussion of an anime director or an anime studio. 100 Anime also does not offer such typical genre categorizations as "drama" or "comedy" although you will find such thought provoking descriptions as "Mutant Sci-Fi" or "Urban Power-Suit Melodrama."

What 100 Anime does offer is a brilliantly conceived no-holds barred embracing of anime as an art form unto itself, an art form that is resolutely "other" in relation to live action cinema, photography, and Western animation. Brophy plunges into the sometimes dazzling sometimes dark torrent of anime's unique visual and aural qualities. Brophy refuses to discuss anime in either implicit or explicit comparison to more referential media because he feels that would inevitably stigmatize it as "not-cinema." Instead he sees anime's mission as mapping an "alternative 'unreality' on its plane of materiality." (3) This mapping seems to be a guiding principle that he finds in Japanese pop culture in general which he sees as "consistently privileg[ing] the imagined over the authentic." (132)

The book is worth buying for the introduction alone. Brophy really looks at what makes animation and anime so distinctive. Among his most salient points are the "energized form" that helps anime "exploit the dynamism of movement" (9) and stimulates the medium's obsession with metamorphosis. This insight has been available elsewhere but Brophy links it to the "mannequinned form", anime's fascination with the posthuman and the "mega-ornamental, hyper-extended figure." (15) that characterizes so many anime bodies. He also includes a short discussion of anime's "sonic aura" that explores the interaction between sound and silence in anime in a thought provoking section that I only wish had been longer.

Brophy also tries to link anime to certain aspects of Japanese aesthetics. On the whole he does this successfully, or at least provocatively. His most effective analysis is in his linking with the surface and decorative nature of Japanese traditional art (such as screens and woodblock prints)with the diagrammatic flatness of anime, suggesting that "[d]epth in anime is best characterized as an arrangement of flat decorative screens which appear to be progressively behind each other while contrarily declaring that the implied depth is but the limited expanse of the staged image." (14) Perhaps a little more problematically, he also finds "Zen form and space" (10) and a "calligraphic momentum" (10) behind some of anime's unique elements. While I don't necessarily disagree with these ideas, I wish they might have been balanced with a discussion of some of the important elements that Japanese animators have taken from Western animation.

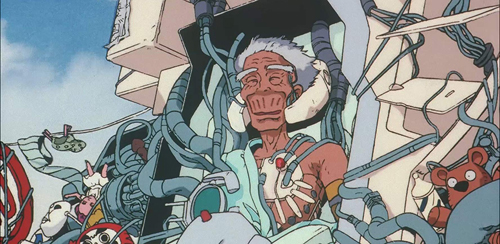

The rest of the book consists of two page discussions of some of the most interesting anime that has been created in the last four decades. Ranging from Kimba the white lion in the 60's to such recent work as 2001's Spirited away, they are useful for anyone wanting a quick reference to a wide variety of anime. But Brophy's discussions are far more than just plot synopses (although he does provide a little of that as well). Rather, they are dazzling and provocative analyses of these works as artistic entities unto themselves. Thus, although you will not find a discussion of Miyazaki Hayao's humanism in his entries on Spirited away (Japan 2001) Kiki's delivery service (Japan 1989) or Mononoke Hime (Japan 1997), you will find a thoughtful discussion of the characters' development combined with brilliant explorations of how the animation serves to delineate the characters. For example, of Chihiro in Spirited away he writes that she "moves throughout…like a puppet of unbelievable realism. Her complete being is expressed more by mime than by mimetics….Thus, her mobility is rendered frail, unsure, traumatized. When she moves down treacherous steps to the workhouse of Kamaji…the elongated scene is a miniature 'rite of passage' through bodily control, lingering over every move no matter how slight."(220) In a few sentences Brophy shows how animation can make a convention "rite of passage" trope into something memorable, touching, and unique.

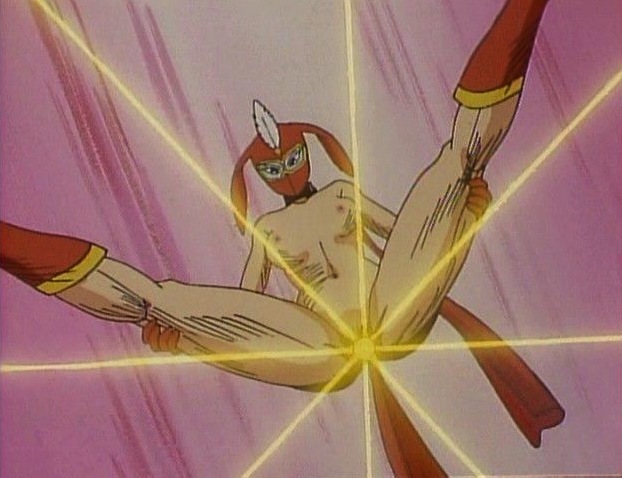

Almost every one of these 100 mini-essays contains at least one such interpretive gem. Brophy's discussion of Adolescence of Utena illuminates the doll like aspects to Utena and her crew but goes further, pointing out that the Baroque space she inhabits is "not merely a hermetic social sphere but a Russian doll of interior and disguised realms of sexual conflict and gender multiplicity." (18) Even his essays on such pornographic/erotic works as Cream lemon and Urotsukidoji, while not attempting to see them as great works of art, still give the reader the sense of what makes them strangely watchable, as when he links power, dynamism and sexual energy in Urotsukidoji's demon tentacle sex scenes.

There is little to criticize in 100 Anime. My main criticism is a compliment - I only wish the book were longer. As it stands, the book is a dazzling entrée into a world where unreality holds sway.

100 Anime

published in Senses of Cinema No.39, Melbourne © 2006

by Lucy Wright

If Philip Brophy was an anime character, he would have tentacles growing out of his eyes.

Seriously. He would use them to pick up on the strange kinetic energy and subtle tactile vibrations emanating from his TV screen, permitting him to perceive anime (Japanese animation) in a fresh way. His new book 100 Anime is attuned to this art form’s frenetic frequency. In Brophy’s inimitable fashion, the book is filled with neologisms and pithy insights. He invites the reader to “dive in – things become viscous, shiny, loud” (p. 2).

To those familiar with Brophy’s work (as curator, speaker, score composer, writer, director, etc), it should come as no surprise that he is advocating an immersive and energetic engagement with anime texts. As with the “cacophonic sensurround” environment he created for Kaboom!, the animation exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Sydney in 1994 and subsequent edited monograph (1), as well as the various articles he has published on anime, Brophy brings vicious yet infectious energy to his work (2).

But, in the absence of eye-tentacles, Brophy instead prescribes for the viewer a rewiring of certain bodily systems – synaptic, musculatory, auditory, optical, skeletal – in order to access the dynamic anime experience. He suggests that the tweaking of these networks will enable appreciation of the corresponding five key elements of anime: “energised form, calligraphic momentum, sonic aura, decorative surface, and mannequinned form” (p. 8). These five features form the basis of his theoretical framework for approaching an analysis of the films. “If anime is a body, no existing medical practice is suited to examining it” (p. 7).

There are other anime books out there, but in the main they are chatty fan texts such as Gilles Poitras’ Anime Companion (1999), Helen McCarthy’s Anime Movie Guide (1996), and Antonia Levi’s Samurai from Outer Space (1996). All are handbooks to navigate the “wacky” Japaneseness of anime, written for a predominantly American audience (see Levi’s chapter title, “Disney in a Kimono”). These books provide a peepshow into Japanese culture for an audience interested in the Other-ness of Japan.

This “numbing transliteration” (p. 4) is precisely what Brophy attempts to bypass in his idiosyncratic approach. He doesn’t want to understand Japan through Occidental goggles. He wants to tune into the text as experience, and the text as texture. While vociferous in his objection to the current trend of framing anime in terms of anthropology (customs and classifications) and kooky cultural difference, Brophy acknowledges the difficulties in approaching the texts as gaijin (outsiders) and the need for some knowledge of Japan’s cultural matrix from which these texts emerge. This is why he places energy at the centre of his argument, making the perception of anime a matter of “tuning in” and “rewiring” the senses. Energy is necessarily cross-cultural. It is in the imaging and drawing of movement that cultural characteristics become apparent.

The reviews and introductory essay offer an intelligent, if frenetic and brief, treatment of the anime genre/form. Brophy has selected titles to reflect the sheer range and complexity of anime-ic texts. It is not a “top 100” or “Anime for Dummies” approach; rather, he has chosen works that are perplexing and strange, artistic and pop-crazed, mystical and cheesy. Each film has a distinctive quality – unusual visual design, satiric narrative, etc. – which merits its inclusion. “The lament over Barbie goes unheard in Japan” (p. 18).

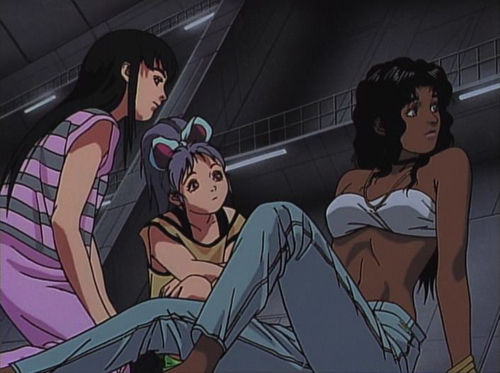

Take for instance the review of Adolescence of Utena (Kunihiko Ikuhara, 1999). A complex and bizarre tale of duels, princes and high school, Utena fits into the shojo (young girls) genre of lissome, cross-dressing, highly romanticised heroes and heroines. Brophy contextualises Utena’s elongated and androgenous body in terms of bishojo (beautiful girl) and Japanese doll culture. Dolls and automata have long played a role in Japanese religious festivals, and robot culture is big business in Japan with Sony developing QRIO (humanoid robot) and AIBO (robot dog), while mecha (giant robot) anime is a hugely popular genre with series like Neon Genesis Evangelion (Hideaki Anno & Ken Ando, 1995-1996, TV series) and the ever-evolving franchise Mobile Suit Gundam (Bandai Entertainment).

Anime and manga mediate this cultural interest in remaking and re-imagining the body. Anime in particular enters into a discourse of post-humanism, where the body is malleable and fluid, can be broken down and built up again. Brophy points to the fluidity of gender roles in the shojo genre as being a site of fantasy and excess, rather than repression: “[Utena] is a hybrid morph of hermaphroditical duality, amplifying the sexuality of each gender rather than cancelling them out” (p. 19). “Sublime in its post-humanism, anime tells the story of a human who dreamt of being a robot – and whose dream one day came true” (p. 16).

Brophy’s introduction takes a fast dash through the big ideas informing critical analysis of anime to date – its relation to manga (comic books), and to cinema, and the medium’s “flatness”. One of the more interesting points is his insistence on the centrality of post-human “transcendence” and “becoming” to any understanding of anime. Anime is entirely about movement between states of being, whether fast or slow. As Brophy points out, “the ‘being’ of a person (which can be one’s soul, mind, blood-line, weapon, limb or organ) is always caught in modes of transition” (p. 7). Likewise, the physical act of creating cel animation is necessarily about advancement and replacement.

This expansive theory of animetaphysics draws on the animism inherent in Eastern religions such as Zen Buddhism, and also on the history of Japanese art. Brophy argues that “Japanese art – including anime – emboldens visual pleasure at surface level while presenting the dense data-encoding that resides within its superstratum.” (p. 14). This concatenation of layers, of surface and depth, is at the heart of Takeshi Murakami’s “superflat” manifesto. Murakami uses the term to explain and critique the stubborn two-dimensionality of anime, manga and Japanese art, and Japan’s kawaii (cute) consumer culture. “Smell the old in Japan – it gleams like new; rub the new – it sounds old” (p. 2).

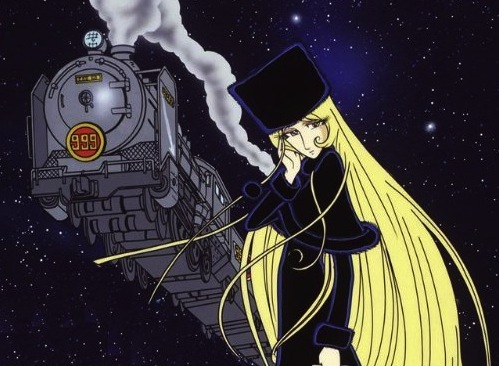

Brophy observes that, in Japan, dualities such as past/future have not suffered under postmodernity’s push to irrelevance; instead, they “mirror each other in their ultimate non-existence” (p. 224). Opposites exist to be played with, to be re-imagined at will. Other epochs and eras are launching pads to imagine a different reality, a different fantasy. In this sense, temporal, spatial and generic differences are elided.

Recently pondering the European steam-engine technology of Katsuhiro Otomo’s 2004 film Steamboy, I was curious to see Brophy’s take on the movie. Brophy notes that “[Steamboy] imagines through vivid demonstrative connections how future and past can be encoded into each other” (p. 223), suggesting that it is irrelevant when and where the imagined past and the speculative future take place. The milieu is simply texture. Otomo, director of the classic Akira (1989), has termed the film “steampunk” in ironic response to the expectation that he would produce another sci-fi cyberpunk film. Like the spherical “steamball” at the centre of the narrative, Brophy posits that the film merges mechanical possibilities and elemental natural power into a uniquely Japanese vision of “techno-nature”. The protracted destructive scene at the climax (which begins about halfway through the film, much like in Akira), as the gigantic steam-powered city-ship destroys most of London, mourns and celebrates this awesome power. “You can neither read nor analyse this: you ingest it” (p. 2).

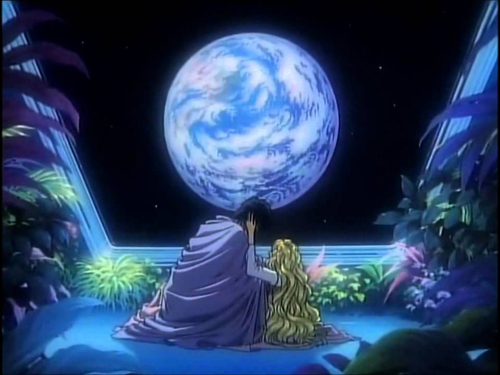

Other notable films reviewed include Blood – The Last Vampire (Hiroyuki Kitakubo, 2000), the sombre Grave of the Fireflies (Isao Takahata, 1988), Metropolis (Rin Taro, 2001), most of Hayao Miyazaki’s films (e.g. Spirited Away (2001), Nausicaa (1984)), and the poignant A Wind Named Amnesia (Kazuo Yamazaki, 1990). Notable absences are the cosmically beatnik Cowboy Bebop (Shinichiro Watanabe, 2001) and Angel’s Egg (1985), Mamoru Oshii’s surreal art piece. Reviews are short (about 500 words) but punchy, generally with a brief synopsis and details of the format, crew details (including producer, score composer, key animators). Films are given cute genre classifications like “gender sci-fi” and “urban power-suit melodrama”.

The BFI Screen Guides are a highly readable and academically adventurous series, and 100 Anime is a welcome contribution to anime literature. Brophy convincingly argues for being “disoriented yet seduced” by anime, and the book will certainly aid digestion of the medium for novice, academic and otaku (obsessive fan) alike. Unlike most other guides, attention is paid to the formal and stylistic elements of the films, and Brophy’s critical insight betrays his long involvement and interest in this art form.

100 Anime

for The Book Show on ABC Radio National, Sydney © 2006

by Rex Butler

It's probably been the world's cultural phenomenon of the last 15 years. It – and its Pop Art counterpart, Superflat – has swept the West, so that no young artist is untouched by it, thousands of clubs have sprung up dedicated to it and millions of websites endlessly discuss it. It's Japanese anime or animated cartoons, and Australian author Philip Brophy has recently written a book about it entitled 100 Anime, published by the British Film Institute.

Brophy cautions in his 'Introduction' that his book is not a 'top 100' or an 'introduction to the world of anime' – and, if you read even a few pages of what he's written, you can see that he is resolutely opposed to any idea of canonical taste or the neutral, objective overview. Instead, as he admits – or, better, proudly boasts – his approach, in keeping with his subject, is passionate, opinionated, animated, visceral.

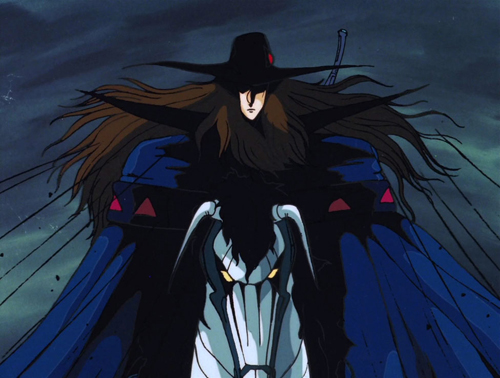

Try this as a sample of his own prose special-effects. Describing one of the many scenes of bodily transformation that occur in Koichi Ishiguro's late 80s/early 90s series The Guyver – Bio Booster Armour, Brophy writes:

Sinewy muscular veins jump out from retracted cavities within his new mutant skin; deep growls rage forth from his genetically affected vocal chords; amplified psychic abilities sense things around him via his metallic third eye implanted in his forehead; and white hot beams of plasmatic energy shoot forth from his breast as he rips open his pectoral muscles in a violent orgasm of polysexual aggression.

And the weird thing is, if you've ever actually watched any anime, every word he says is probably true.

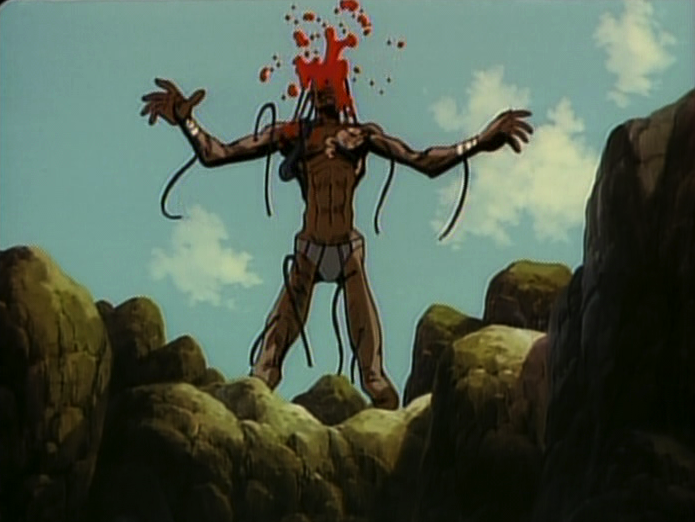

In Brophy's almost ecstatic vision, what Japanese anime depicts – as opposed to Western-style animation – is a world of invisible forces, both natural and spiritual. It is vitalistic but also, confoundingly, mystical. Nothing is still, nothing remains fixed, in a cosmological chain of being in which the greatest is connected to the smallest. In a film like Yoshiaki Kawajiri's Ninja Scroll we see two characters joined by a kind of telepathic whisper across time. In master animator Hayao Miyazaki's My Neighbour Totoro we witness a stunning time-lapse recreation of a tree growing, which reminds us that the natural and geological processes of this world play themselves out on a time-scale much greater than the human.

But the world of anime – for all of its themes of environmentalism – does not propose a vision of the world as Goddess Gaia. The fake New Age Orientalism of a ying-yang or cosmic balance between nature and culture is utterly alien to it. Rather, in films like Jun Kamiya's Blue Seed or Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke the universe is conceived of as a ceaseless struggle between man and nature, in which our relentless despoilation of the planet is returned to us as full-scale environmental catastrophe.

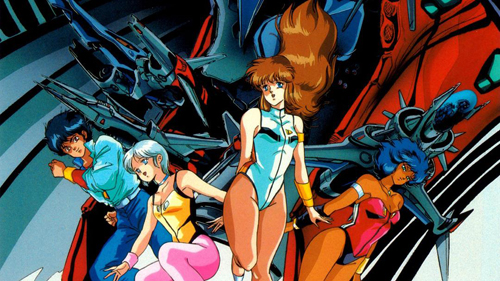

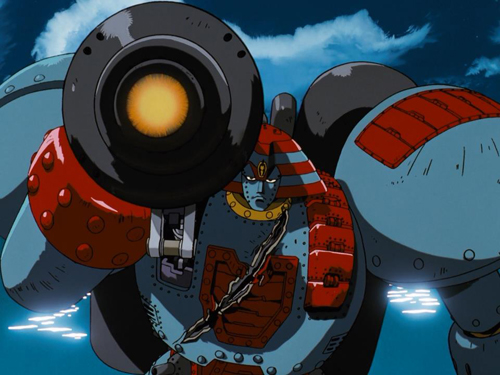

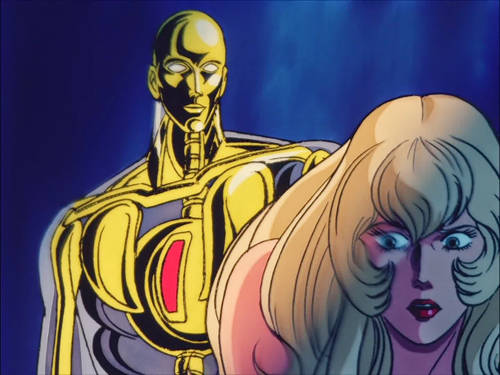

And all this is to say, of course – one of Brophy's long-running arguments throughout the book – that the world of anime is neither humanist nor anthropocentric. Human consciousness is not only not the centre of the world; it is not even in control of the human body. In any number of anime, human identity is put on like a suit of armour, as in Toshihiro Hirano's Hades Project Zeorymer, or befalls one like a fate, as in Hirano's Iczer-One, or is even like a pill one swallows, as in Osamu Tezuka's Marvellous Melmo. In Brophy's pithy formulation, anime 'turns the body inside-out and the psyche outside-in'.

And, if this is the world of anime, then Philip Brophy is just the person to write the book. He was one of the founding members of that inaugural Australian postmodern art movement, Popism, which took up from Andy Warhol and his radical refusal to attribute depth to either the self or culture.

Later he wrote an influential essay, 'Horrality', on that distinctively 80s genre, the slasher or splatter film, in which special effects took the place of characters or in which we saw the inside of bodies and not the inside of souls. He later developed his concerns in a film called Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat, in which among the various bodily functions explored – I will never forget it – was a man excreting on a transparent plastic toilet.

Later still, he became fascinated by the construction of soundtracks for films, which always work for him in an extra-diegetic way, moving beyond any narrative meaning towards the sonic or even somatic.

His work exhibits a consistent 'post-humanism' in the sense of something in the body that goes beyond the biological that we glimpse only rarely in Western culture: Freud's death drive, films like Robocop and by Hollywood mavericks like David Cronenberg, the wound in Amfortas' side in Wagner's Parsifal, Renaissance paintings showing such things as the stigmatisation of St Francis, the convulsive orgasmic spasms and anatomical close-ups of porn movies.

In Japanese anime he has found a whole universe where bodily and psychic impulses are played out on a planetary or even cosmological scale – and his book is full of such strange possibilities as bodily transformations or becomings, fields of invisible energy, the post-apocalyptic and time folding back on itself or repeating endlessly.

But, again, as he stresses – and this is how anime differs from its Hollywood equivalents in such computer generated children's entertainments as DreamWorks' Shrek or Pixar's The Incredibles or such sci-fi space operas as Lucas's Star Wars series – such tensions or dramas are to be reduced neither to those of the nuclear family nor to any anthropocentric upset. The aliens in anime – unlike the cute droids or furry wookies in Star Wars – remain other: there is not the same imperial drive to possess or understand the universe.

In fact, as Brophy emphasises, underlying a whole strand of anime, such as Rin Taro's Doomed Megalopolis, is a critique of the Japanese war-time misadventure of militarism and aggression; but equally, in Isao Takahata's extremely moving Grave of the Fireflies, there is a critique of the decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to hasten the end of the War.

In the feverish, high-pitched, rhetorically over-the-top tone of the book – at moments reading like an online fanzine, at others like a jargon-packed computer manual – Brophy comes close to catching the sheer exhilarating otherness of anime for the Western viewer, the sense of putting one's eyeballs into free-fall while one is watching them. (And Brophy has nothing but contempt for all sociological, historical or cross-cultural efforts to explain them, which are ultimately only so many attempts to tame them, render them once again familiar. As he says memorably: 'Sociology is the cheapest of cinematic divining rods'.)

Since seeing my first anime at the urging of friends some five years ago – Miyazaki's mesmerising Porco Rosso about a pig who is a WWI biplane flying ace, which to my horror didn't make the cut – I've probably seen about 20 of the films on Brophy's list, which includes such classics as Akira, Ghost in the Shell, Neon Evangelion Genesis and Taro's version of Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Brophy told me things I didn't know about the films I'd seen, and made me want to watch a whole lot more.

And you can bet – and this is why 100 Anime could never be a listing of the top 100 anime – there will be any number of new masterpieces of the genre, because this is the big art movement of the 21st century and it doesn't look like ending any time soon.