Chapter II

Sound Check, Sound Test & Sound Stage

published in Stuffing No.2, Melbourne, 1989So now we can start to define the sound of rock - rock as sound. In a way, it's fairly easy, because the history of Western European music is based on definition, upon analyzing and breaking down the event of music into some sort of structural plan. While this tendency is culturally inevitable for us, one must use such plans with caution, especially when they become more concerned with their own planar logic than the music's linear totality. My breakdown of the sound of rock is just as guilty, but I should stress that it will only make sense if you listen to the records I'm talking about to see how you compare your listening perspective with the one I'm proposing. Music and sound are temporal - they are immediate and require immediacy and simultaneity in order for one to experience something which can then be related to a means of detailing that experience.

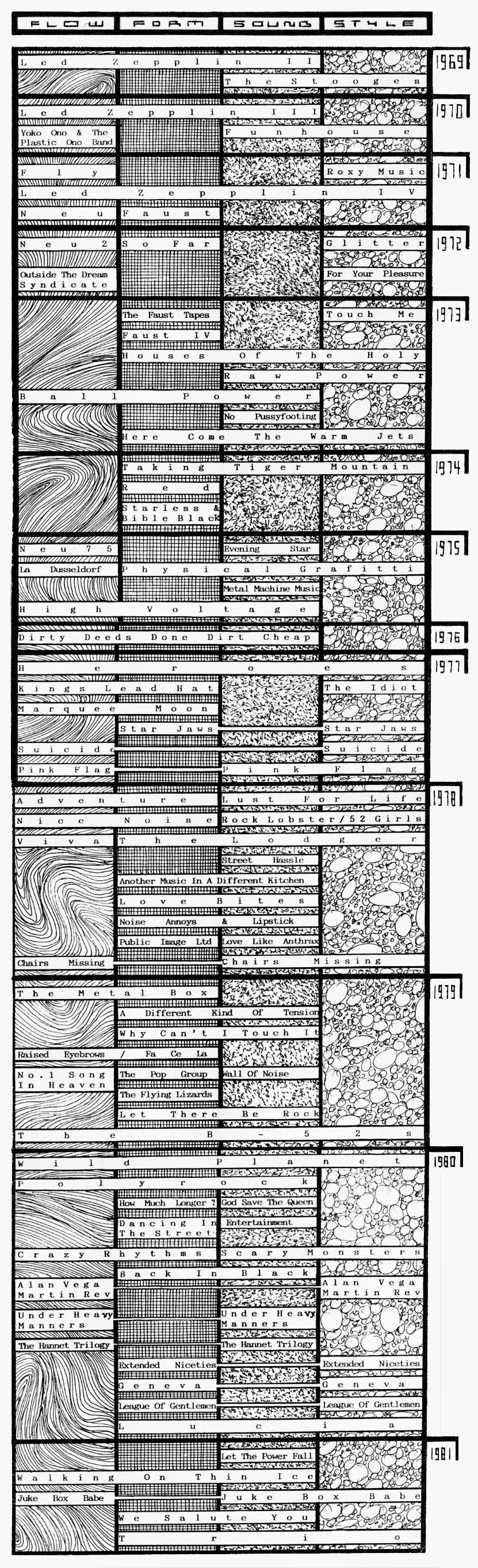

OK - I break down the sound of rock into four primary streams of temporality: flow, form, sound and style. I call them `streams of temporality' because I'm talking about how they exist in time as sound, and how that existence can only be marked and measured during their occurrence and while you're engaged in actively listening. Each stream of course exists with and within each other stream, and focusing on any one stream can only be done by feeling the reverberation of the other three streams upon it. (If none of this makes sense, don't worry. I'm throwing it up this way first for those who want some sort of conceptual base for my argument.)

These `streams of temporality' can be described thus :

![]() FLOW is how the sound moves along; what is the sense of time which its rhythm conjures up, from chugging to driving to floating along, effecting a feeling of movement, of moving along as you listen to the music.

FLOW is how the sound moves along; what is the sense of time which its rhythm conjures up, from chugging to driving to floating along, effecting a feeling of movement, of moving along as you listen to the music.

![]() FORM is the overall shape and structure of the music; how it has been built and made up; how it has been designed, planned and executed, giving you a sense of the songs an object, a sculpted and crafted thing.

FORM is the overall shape and structure of the music; how it has been built and made up; how it has been designed, planned and executed, giving you a sense of the songs an object, a sculpted and crafted thing.

![]() SOUND is the texture and surface of the music; its tactile feel and its material presence; its prime sonic impression upon your ears.

SOUND is the texture and surface of the music; its tactile feel and its material presence; its prime sonic impression upon your ears.

![]() STYLE - unlike the other three streams - is not a honing of raw materials, but a secondary processing, dealing with an awareness of what images the music can suggest and how previous sounds developed such communication.

STYLE - unlike the other three streams - is not a honing of raw materials, but a secondary processing, dealing with an awareness of what images the music can suggest and how previous sounds developed such communication.

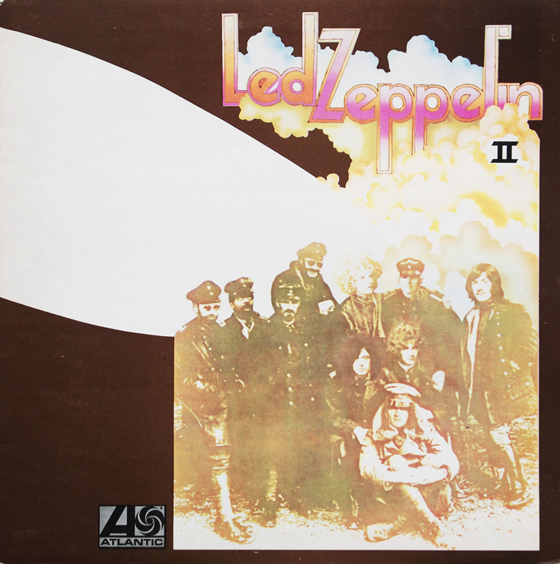

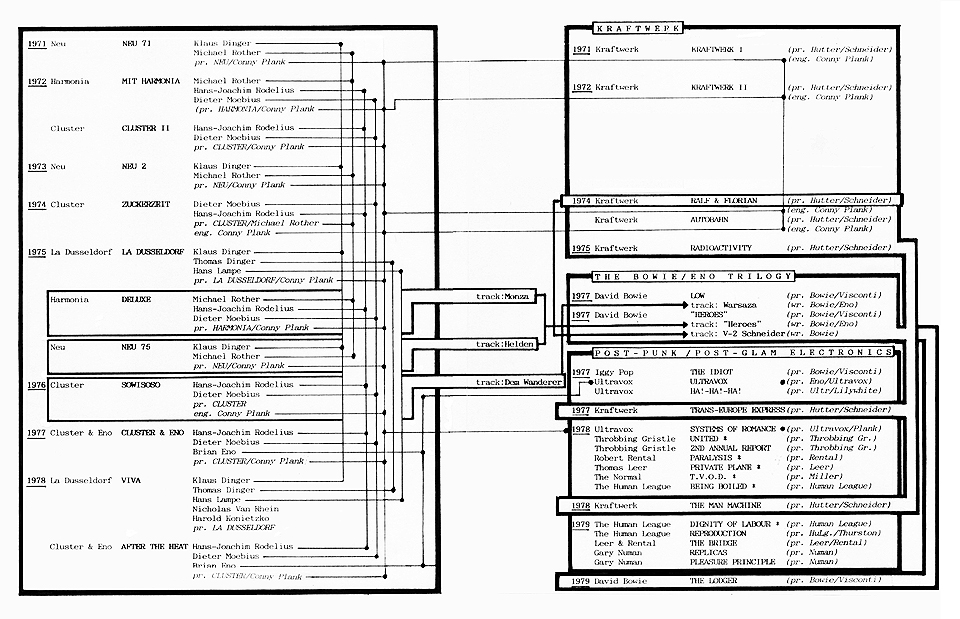

This second chapter will therefore trace a wide range of records which carry on the legacy I outlined for The Ventures (combo rock), The Arrows (soundtrack rock) and Led Zeppelin (hard rock) - their reverse purification of rock music which returns it to its raw state, its definitive status as sound. Each record cited shall be discussed (a) in terms of how it fits in within one or more of those `streams of temporality' and (b) under the historical conditions of its placement, ie. in line with what else was happening in rock at that point in time. As a reference guide, I've detailed a chart you might want to refer to occasionally (Chart II). It's been designed so you can read it four ways : each record can be located and placed (i) in a chronological position by its year of production; (ii) in relation to other records produced in the same year; and (iii) as an indication of whether its approach to generating the sound of rock covers one or more of those `streams of temporality'; plus (iv) each of those streams can be gauged in terms of their own chronological development. (Note : while this chart is presented as an overview of how the sound of rock has developed throughout the seventies and into the start of the eighties, not all records listed are covered in this Chapter and will be covered in ensuing chapters beyond this publication.)

Led Zeppelin: Rock, Rubble & Rhythm

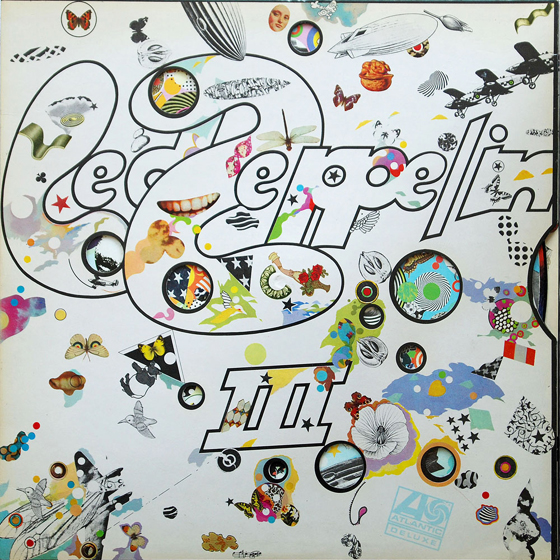

Led Zeppelin III (1970) makes a confident entrance into the seventies with a strong development from their second album, demonstrated by the vigour with which it further tackles the blues-rock collapse. Tracks like The Immigrant Song, Friends and Gallows Pole virtually replace the African/Caribbean lineage of blues roots with an unearthing of Celtic and Nordic modals and scales - that weird `ethnic' feel, if you like, which typifies the unusual tonality in their music from this album onwards. Perhaps this is the result of Page's preoccupation with Alister Crowley mixed with Plant's dabbling in English rural mysticism, but whatever the case this album marks Led Zeppelin's skillful containment of a multiple of `roots musics' - celtic tones, blues themes, folk embellishments - within a solid rock structure.

This multiplicity is of course echoed in Page's guitar sounds. They just get weirder with each album, as he - producer of all their albums - further experiments with guitar sounds, like on Out On The Tiles: it hovers once again halfway between electric authenticity and electronic artificiality. Going beyond their second album, Led Zeppelin III also experiments with acoustic guitar textures, from the chorus of jangling 12-strings on Friends to the combination of electric and acoustic twanging in Tangerine to the raspy, breathy yet spaced-out slide work on Hats Off (To Roy Harper). Compare these `softer' moments with, say, the convention of Black Sabbath always including a ballad on each album to demonstrate their `versatility'. Such attempts at ballads usually have you thinking "stick to the hard stuff". Some of Led Zeppelin's more subtle moments work because their songs are integrated, welded into conglomerations that are `structurally sound'.

This aspect of conglomeration is also one of the key distinguishing traits of this album. Overall, we have the same shifting of the rock machine's gears as on their second album, but coupled to this we have an even more eclectic approach to stylistic mutation : the synthesizer drones emerging toward the end of Friends; the Hendrix-styled solo in the middle of Tangerine whose verse-chorus switch replicates a shift from folk to country & western; etc.. Perhaps the best example is Gallows Pole (a traditional folk tune rearranged by Page and Plant). It starts off like a semi-acoustic revamping of the blues boogie from Whole Lotta Love. With the chorus it then lets loose a strong English folk flavour with a mandolin carrying a rising and falling melodic counterpoint. The bass comes in the next chorus, weighing it down again towards an electric blues leaning, but just as that stabilizes, some bluegrass banjo-plucking enters to play along with the acoustic guitar. The bass then drops an octave, as if it's reaching the sediment of this melting pot, and the drums erupt (halfway through the song!) playing a counter-rhythm (similar to that on Celebration Day) which simultaneously suggests mod's frenetic on-beats and the hobo chugging of wash-board scraping. Weird or what? And listen to the solo during the extended fade-out as it ironically swaps from blues licks to country lines, playing with your focus on the blurring styles. Yet somehow this song all flows together, as if each phase emerges from each preceding phase. If this was recorded ten years later in 1980 it would be hailed as avant-garde. In 1970, it's rock.

If Led Zeppelin II is the group's notice of blues-rock demolition, and Led Zeppelin III their architectural wondering of what shape their rock will take, Led Zeppelin IV (1971) is their habitation of the structure they developed out of the other two albums. Strangely enough, the cover to this album (the decaying inner walls of a building being knocked down just next to where a block of high-rise flats have been erected) is a perverse play on interior/exterior forms and past/present styles. You could say that on this album Led Zeppelin are either being deliberately destructive or bluntly realistic, as they appear to have accepted the rubble but still continue to fiddle with plans for a new abode. This is exemplified by how the album withholds (a) a yearning for old rock'n'roll; (b) a fascination with how far it could stray from rock music; (c) a strong impulse to smash anything in sight; and (d) a fastidious melding and forging of new structures and sounds. As it turned out, Led Zeppelin never made up their mind to head in any one of these directions to the exception of the others, which is probably what makes their records sound so fresh today, and what makes the `straighter' (ie. non-conglomerative) records by Black Sabbath, Uriah Heep and Deep Purple sound comparatively stale. If anything, Led Zeppelin IV is the realization that this would be their strongest fix on the sound of rock : hovering, displaced, continually slipping between fixtures and conventions of how to play rock music. Such is the sense of `flow' that emerges on this album : solidifying rock music only to break it up again so they could conglomerate it back together with new elements to then stretch the whole thing back out of shape. A multi-dimensional state, equally stretching across all four streams of temporality - flow, form, sound and style. More importantly, this ended up being the unspoken nature of Led Zeppelin, leaving them to generate all the first degree copies like Foreigner, but also eventually all the second degree `mutant' approaches to rock composition throughout the seventies and eighties.

The opening track proclaims all of the above. Black Dog is a raunchy rock'n'roller propelled by the complexity of symphonic rock's most daunting time signature tendencies. I could be wrong, but I think the song is in something like 15/4. In the hands of a jazz fusion outfit you'd be in techno zombie heaven, but Led Zeppelin manage to keep the song driving along at a near-thrash intensity, with Page's monstrously mutated 12-bar riff running wild for each verse burst until it falls dead to let Plant screech some vocals about his mama shakin' her hips. Of course it's all held together by Bonham's incredulously simple drumming : here - as in the previous album's Celebration Day - he counterpoints his almost lumpen phrasing against the askew rhythmic structure of the verse-chorus blocks, thereby intensifying their strange timing with his `implied' off-beats. Perhaps the whole thing is in straight 4/4/time, but everything seems to be playing out of synch, while the overall drive and flow just cruises along.

The album's hit single - Rock'n'Roll - is not as much a retro statement caught up in the seventies' rediscovery of fifties rock'n'roll as it is a demonstration of how noisy rock music had become by 1970. In this sense it is an abstracted caricature of rock'n'roll's mythical essence, because its sound demonstrates that the way in which old rock'n'roll is listened to in the seventies totally distorts the original artefact anyway. Rock'n'Roll subsumes this listening perspective into its sonic styling, giving us a rushing wall-of-noise boogie woogie, topped off by Bonham's reworking of the arrhythmic spluttering at the end of Bill Haley & The Comets' Rock Around The Clock. Rather than turning back the hands of the clock, Rock'n'Roll jettisons that era forward into the seventies, for us to hear neither the real thing nor the original version, but a sonic image of how times have changed and how different is the sound of rock.

That difference is coded in hard-to-classify tracks like Misty Mountain Hop and When The Levee Breaks. Misty Mountain Hop is downright atonal. Its chords and harmonies are more invented than adapted, giving the song a dark and creepy feel. The strangest thing is that the core riff is basically a rockabilly line played against a non-swing timing - the riff being of the classic `voodoo style' idiom which appears on numerous rockabilly numbers (Jett Power's Go, Girl, Go for example). Page is thus taking a standard slice of past generic effects and altering it slightly to produce a modern effect. Conversely, When The Levee Breaks finds itself treated in this way when its opening drums are sampled for The Beastie Boys' Rhymin' & Stealin' (1986). I say `conversely' because whereas Page alters the standard into the modern, Rhymin' & Stealin' transforms the modern into a standard by using only the first 4 bars from When The Levee Breaks to loop it into a pastiche of a hard rock beat. The point is that the original Led Zeppelin track is a precise example of how unconventional and unstandardized John Bonham's drumming is. In When The Levee Breaks he designs time architecturally - that is, he blocks out and breaks up time with sonic bursts, punches, holes, gaps and accents. True, the sound and tempo are very heavy, but the drums' structural organization overrides their superficial qualities. And listen to the sound of the crash cymbals on this track : their dynamics have been so flattened out they don't highlight rhythmic points as much as they appear and disappear as sheets of hiss, erupting from and filtering back into the sonic blocks Bonham arranges with his booming snare pounds and kick punches. At the other extreme from the mad thrashing of Keith Moon's `hit-everything-at-once-non-stop' method, Bonham is very restrained in his use of cymbal crashes to mark points because he has already designed his beats as part of a self-stating rhythmic totality.

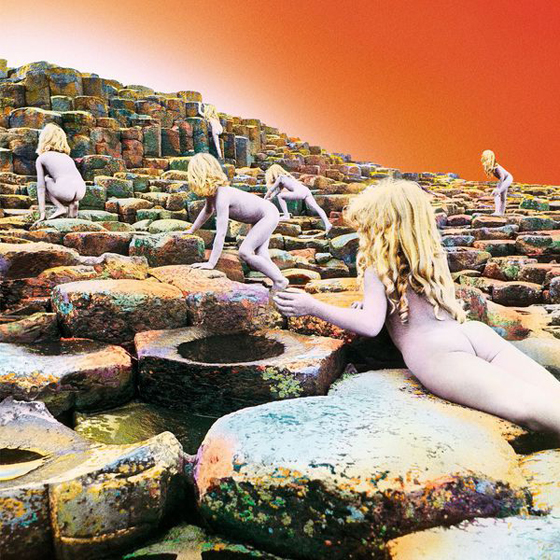

Houses Of The Holy (1975) is a journey to an alien place. Gone is whatever house Led Zeppelin set up on the previous three albums - we're now on foreign land. This is not simply because the album laterally plugs into the reggae influence which started creeping into rock around this time with labels like Island Records bringing Jamaican artists' music to white rock markets. The single from this album - D'yer M'aker - is an obvious pastiche of reggae's mellower side, referenced by a title that refers to the old Benny Hill-type joke about sending your wife to Jamaica for a holiday (no she went of her own accord, boom-boom). But away from obvious stylistic traits, the real foreign terrain outlaid in this album lies in Led Zeppelin's reinterpretation of reggae, ska and dub rhythmic structures and shapes - the point being that they've been so radically altered and cut up they bare little resemblance to reggae as style, but there is a clear difference in the rhythmic sensibility running the Led Zep rock machine this time around.

More so than their other albums, there is a relatively consistent feel to the ways in which rhythms are organized, with many key riffs and chord sequences privileging the off-beat. Theoretically, this is the basis of most reggae patterns, but the alien effect of Houses Of The Holy is the way Bonham's drumming weighs down the off-beat. Just as they solidified the blues and hardened rock on their previous albums, they now transform the wispy, hypnotic floating of reggae's articulated spaces and gaps into a heavy, hesitant rhythmic patterning : hard rock reggae. On the one hand this is fairly inevitable - four Brit heavy rockers trying to colonize the skipping, skitting Caribbean beats - but on the other hand it is Led Zeppelin continuing their containment of world rhythms within the machine-age framework of hard rock.

This rhythmic approach accounts for the increased compound time signatures and odd-numbered bar counts for songs like The Cringe, Dancing Days and The Ocean, which deliberately throw the listener out of step with the songs' rhythmic flows. The smooth car is now bumping along new roads, and the best ride is perhaps The Crunge. Recalling the unreal timing of Black Dog but minus the hard rocking image that song conjures up, The Crunge - true to its title - gives us a rhythmic cut-up that is almost bebop or cubist in its fracturing of a discernible pattern; playing like a record with an awkward jump, but jumping perfectly in the same spot each time. Complex associations arise with the decidedly funky flavour of Page's guitar work, like the high, brittle one-chord line straight from James Brown's late sixties period, coupled with Plant quoting Brown's famous command "Take it to the bridge!". The funky stylizations continue with some harmony synth lines borrowed straight from Stevie Wonder's synthesizer multi-tracking circa Talking Book (1972). It's a strange conglomeration that doesn't resurface until the fractured blues-funk mergers of groups like (on the black side) James Blood Ulmer, Defunkt, Funkapolitan and The Decoding Society, and (on the white side) Material, James Chance, Au Pairs, Medium Medium, Maximum Joy and A Certain Ratio - all a decade later.

Visions of such futuristic efforts persist in Dancing Days's slide guitar which - when mixed with its atonal neo-jazz chords and riffs - mixes Hawaiian music with some of Page's own long-gone distortion sounds from The Yardbirds. Its cultural clashes here mark Led Zeppelin's work not as fusion - as the harmonic cancelling of styles into each other - but as polyglottic: evidencing the uncomfortable meetings and mutations of styles, forms and sounds brought together under a conglomerative logic. When you play this song and similarly constructed tracks like The Ocean, The Song Remains The Same, No Quarter and The Crunge now, they just don't sound like they're from 1973. Not that everyone I mentioned above knows Houses Of The Holy backwards, but simply that Led Zeppelin - `the greatest rock band in the world' - were unbelievably ... progressive. Strange but true. Perhaps a decade ago their music did sound `down to earth' - though I suspect that such a feeling was generated by how solid their songs were. As for how they are now - they're simultaneously definitive examples of hard rock and prime examples of modernist rock. Perhaps the trick was (as mentioned earlier) they did their experimenting on the inside - inside the music's construction, inside the grain of its textures. Inside, where rock is sound. Consider the opening track's title : The Song Remains The Same. It's not an ode to tradition, but a hint that the changes happen not on the outside, where rock is image, but elsewhere; within, where all styles, all histories, all conventions can touch each other, blend, fuse. As the lyrics say :

"California sunlight, sweet Calcutta rain. Honolulu star bright - the song remains the same. Sing out Hare Hare, dance the Hoochie Koo. City lights are oh so bright, as we go sliding, sliding, sliding through ..."

The German Occupation

Krautrock. An early seventies phenomenon, hailed as experimental, avant-garde, underground, progressive ; railed for its introspective, para-hippy meandering. Today, it's all but disappeared, save for some wispy, evaporative traces caught in the laser glare of new age CDs. But as regards the sound of rock, it's a very important phase, mainly because it resulted from Germans listening to rock music and playing it back under their own environmental conditions. These results are many and varied. Some sink into the worst of cosmic/metaphysical rock lethargy with groups like Popol Vuh, Amon Duul, Ash Ra Tempel and Can ; others sail off into a mindless mellotron heaven like Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze. Being a genre, krautrock's image is inevitably conveyed by its worst exponents. There are some exceptions to that image.

The exceptions (for the purpose of this chapter) number two : Faust and Neu. Through their distorted way of listening to rock - neither right nor wrong, but simply a variant of the norm - Faust and Neu took rock and did things with it that few Anglo or American bands had ever considered, save for the radical alterations performed in the late sixties by The Mothers of Invention on rock'n'roll and Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band on the blues. In a sense, Faust and Neu occupied the Trans Atlantic territory marked out for rock's sixties-seventies' crossover. They didn't particularly aspire to carry on any traditions, nor desire to transform any norms ; they simply but incisively took rock over for a while on their home turf, and recolonized it for a few experiments of their own.

Based in Wumme, Faust concentrated on deconstructing rock by surveying the architectural and archeological remains on sites such as those which Led Zeppelin had opened with the release of Led Zeppelin IV (1971). Culturally displaced by whatever blues/rock/hard-rock precepts were being established in England and America, Faust were able to view rock's formations from a distance, using their view to produce not an irrelevant or inconsequential angle on rock composition, but an approach unimaginable outside of Europe. Despite the image of Europeans being incapable of delivering rock with guts, Faust gave us some of the most severely fractured interpretations of rock form, draining it totally of any potential conventionality in its appearance, and giving us rock in a wholly dissected and disemboweled state : rock with its guts exposed.

Adopting a very different approach, Neu (based in Dusseldorf) didn't want to break rock apart - they wanted to exist within the grain of its sound and thereby flow with it. For Neu, rock was primarily movement and secondarily structure. Their sound had that floating feel typical of a lot of krautrock, yet they stuck defiantly with traditional rock instrumentation (more so than Faust) and produced a sound which conveyed the dynamic energy and motor appeal of rock - a feeling not unlike that generated by Led Zeppelin's careful tapering and refining of their arrangements, which always allowed their songs to drive along despite the weightiness of their structural density.

Faust: Rock Doctors

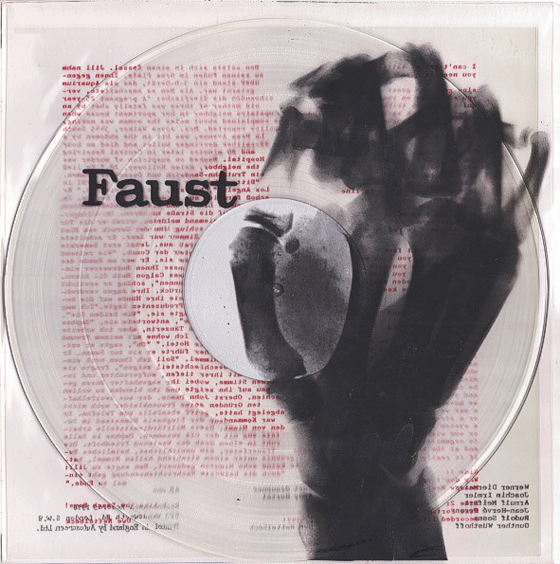

The cover to Faust's first album Faust (1971) is not arbitrary. That x-ray of a hand printed in black on a clear cover encasing a clear vinyl record is a stark sign of their analytic dissections of rock's means of production. They didn't just play rock ; they wanted to find out what it was that made them able to play it. Their sound is thus self-analytical in that this album (in particular) is a series of rock experiments conducted on a group, with Faust being both doctors and guinea pigs : the guts of rock they expose are their own. However, comprising of only three long tracks - Why Don't You Eat Your Carrots?, Meadow Meal and Miss Fortune - this album perhaps explored too many tangents for its own good, leaving most of it to sound like a collision between early Floyd and Zappa. These art rock influences reveal themselves in the album's neo-dada/absurdist lyrics and the sometimes forced changes in musical styles. Still, there are scattered moments when they generate some noise whose gnarling textures are more rock than anything else.

Their next album So Far (1972) takes a firmer grasp on the tangents shooting off from the first album, and thus gives us a distinct range of styles and tones, often contained individually within certain tracks. Some of them really rock. The final section of No Harm has an impressive mix of harsh, abrasive synthetic noises and multiple guitar fuzz and feedback, all being churned around and propelled along by a driving rock beat reminiscent of Yoko Ono's early seventies' wild rock. The title track So Far is a mesmerizing, evocative mix of distant guitar distortions sweeping behind a blues-based chugging rhythm, marking this song as an imaginative mix of krautrock's dronal rhythms with the Blues' repetitive `bar' structures. The result simultaneously rocks and hypnotizes, evoking both the hum of the highway and the clickety-clack of the railway track. But perhaps the most trance-inducing song on the album is the infamous one-note metronomic pulsing of It's A Rainy Day, Sunshine Girl where they minimalize a Beach Boys' sensibility down to a few grains of sound. Listening back to it now, it truly is dry, wry and sly with its mock romantic affectation underplayed by its droll execution, and clearly stands as a precursor to the similar mix of minimalism and mimicry in Eno's Baby's On Fire (1973) and Kraftwerk's Autobahn (1974).

The `unofficial' third album by Faust The Faust Tapes (1973) takes to the extreme their method of dissection, with not so much an `album' as a collage of short excisions, experiments and exercises in rock sound and noise. Each side is a continual onslaught of jazz and rock collisions, where mutation reigns over fusion, not unlike The Mothers Of Inventions' more considered albums like Uncle Meat (1968) and Burnt Weeny Sandwich (1969). Though hard to specify any tracks, the album contains moments or points where rock becomes so fragmented it flys apart into a free-form frenzy typical of modern jazz, and other parts where jazz stylings are so distorted they degenerate into a rock-derived cacophony. The violence of these sonic and stylistic fractures has more impact than the comparatively arbitrary fragmentation of their first album, which sounds more stilted and less forceful. Their earlier accent on fragmentation is perhaps what the English were attracted to, and what also makes some of Faust's `arty' material a precursor to groups like Henry Cow, Art Bears and Slap Happy (the latter whom recorded with Faust for the Slap Happy album Acnalbasac Noom, 1973, after Anthony Moore, Dagmar Krause and Peter Blegvad established relationships with Faust via Polydor and Virgin Records).

But The Faust Tapes signals a distinct change from the deliberated fragmentation of the first two albums. It takes the `radio effect' which they stylistically incorporated into the start of Why Don't You Eat Your Carrots? (static breaking into The Beatles She Loves You and the Stones' Satisfaction) on their first album, and turns that effect into a process, using it as a basic flow chart for this album's structure. It's a `radio effect' not because it simply recreates the sound of radio station switching, but because it suggests that everything Faust has digested as influence has been via the disembodied, alien, transparent cracklings of music transmitted from an unknown region and from equally unknown states of mind. Taking this into account (especially in line with American rhythms and sounds filtering through German radio during the American occupation of Germany after WWII and throughout the Cold War, where and when Germans were listening to Americans listening to American records - transmitted on technology perfected by the Germans!) Faust's view of rock `from a distance' is very much what I termed earlier an environmental condition. It's not only cultural and territorial - it's also technological : hearing sounds, feeling them and reacting to them, but ultimately responding to them as sound because there is no real knowledge or understanding of how those sounds came to be produced within their original cultural environs. The Faust Tapes is thus not unlike switching between stations on short wave, where signals float in and out, sometimes intercut by cross-talk and feedback, sometimes doubled up as multiple frequencies clash - a technical method highlighted in Karlheinz Stockhausen's seminal electronic/musique-concrete/radio-mixage fusions like Telemusik (1966) which clearly influenced many German experimental rockers. This `radio effect' of course forms a substantial subtext to the global spread of rock'n'roll, where many countries and regions misinterpreted musical styles as the result of inevitably warped listening perspectives developed from picking up distant radio stations playing `new and unheard sounds'.

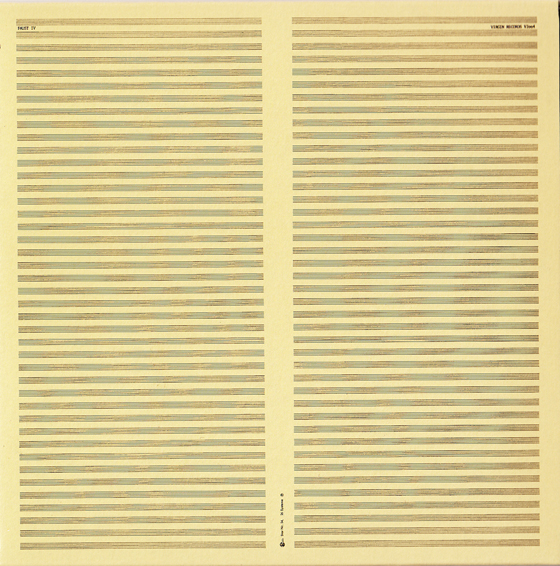

By the release of their fourth and final album Faust IV (1973) Faust had just about broken down rock as much as they could, marking this album's severe sonic severing as their most violent analysis. Along with The Faust Tapes it shows their shift from making arty musical gestures to serious sonic statements. Just A Second opens with the first few fuzz guitar notes from the `rock' part of The Beatle's Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. It's virtually a direct quote, which then blows out into a wall of rockin' sixties-styled noise, giving the track a very cynical feel (considering that The Beatles mostly played at being a rock band). This is then gradually eaten into by some harsh synthesizer gurglings (a la early Kraftwerk) blended with some spacey jazz-based improvization, both of which make you totally forget the hard rock that preceded them. Similar sonic destruction lies in the fuzz hammond organ (!) which demolishes the pre-4AD reverbed melodies of Lauft ... Heisset Das Es Lauft Oder Es Komt Bald ... Lauft; the sweeping, swirling noise guitar which drowns out the folky Jennifer like a gigantic blast of short-wave ; and the incredible fuzz guitar distortions that send the Davie Allan sound into hyperdrive on the solo of The Sad Skinhead and the end of It's A Bit Of Pain. These two last examples of guitar over-distortion on the one hand might be the end of Jimi Hendrix's sonic screeching, but on the other hand the start of Adrian Belew's elasticized, electronic feedback wails. Whatever the case, Faust's extreme guitar sounds mark such a transition by literally scratching the vinyl.

While the bulk of Faust IV deals with sharp-edged, short-wave radio effects (where things are sliced and pierced into each other in comparison to the butted collages on The Faust Tapes) it also delivers two tracks that rock in the most basic and fundamental way : Picnic On A Frozen River, Deuxime Tableau and Krautrock. Picnic On A Frozen River as a track needs some clarification here. It was first recorded on So Far, but its second version here is much stronger. On Faust IV it actually is butted up against the second half of Giggy Smile, and things are made even more confusing because it appears that the track listing for these two songs are the wrong way around. Anyway, Picnic On A Frozen River proper sounds uncannily like some of Mike Curb's biker backing tracks, except here played with a lot more punch. Listen not only to the riding melody, but also the two or three fuzz-wah guitar solos swimming around underneath. Ewe Nettelbeck's production has a rawness similar to those `boxed-in' sounds on Curb's work, but this time with a more grating edge to the fuzz textures. At the other extreme, Krautrock is dense, muddled, confused, distorted, thick and overpowering. It is a true wall-of-noise where individual details are lost amid the massive presence of all details locked together. All the same, the song pushes itself along with force, and sounds not unlike a whole stack of heavy metal and hard rock records all played at the same time very loudly in a large hall.

With a title like Krautrock, one wonders whether this is Faust taking the piss out of the term. Possibly. But sound-wise, it generates the effect of all rock histories dissolving into each other, of all rock voices drowning each other out in one big short-wave mixup. Not the sound of rock but its noise: a communication overload. In a way it is like their answer to that middle section of Whole Lot Of Love, but whereas that song is the dispersal and transmission of all its fragments, Krautrock is the reception of fragments. It returns all the sonic tissue and matter from the experiments on the previous three albums back to their laboratory origins, back into the Faust corpus where they conclude by naming themselves and their discovery `krautrock'.

Neu: On The Road

While Faust received certain critical acclaim in the UK, Neu was possibly the most overlooked group from the kraut attack, yet also the most `rock-sounding' of them all. Whereas Faust's Krautrock worked as a cyclical closure of their analysis of the sound of rock, Neu took such a styling - that driving wall of noise - and mobilized it beyond the remains Faust left behind and took their occupation of rock on the road.

Neu's first album simply titled Neu! (1971) typifies the style they developed through their three-album output : a driving, steadfast 4/4 rock rhythm propelling a one-chord tonality. It sounds boring when described, but the effect is like a continual flow which is more concerned with maintaining the flow than calculating its direction. The result is not trippy and spacey, but hypnotic and mesmerizing. In short, it is the definitive fusion of minimalist compositional form and rock instrumentation. The opening track Hallogallo sums it up : perfect driving music because all it does is drive. It has areas and aspects of light and shade, but overall it has an impressive consistency, constancy and constituency. Fusing density with simplicity, Klaus Dinger's drumming - at the other extreme of Bonham's concrete constructions - lets forth a gushing flow which simulates a drum machine, with the kick hitting on every beat so that there is no chance of the music breaking itself into any rhythmic demarcations. It just starts itself up and goes, and keeps on going like a droning pulse.

Two other tracks posit Hallogallo's style and form as central to the Neu sound : to one side the more lyrical, slowed-down swaying of Weissensee and to the other, the hard-edged frenzy of Negativland. Weissensee is interesting because its baroque, wah-wah guitar licks floating over some more fleshed-out drumming make it lean towards Pink Floyd's wandering jams. The major difference is that where Pink Floyd play out that tawdry sense of theatre and drama in their jamming (build-up/climax/come-down, over and over again) Neu stick to a kind of `groove' where a certain contentment with repetition is effected. It's not `easy listening' but rather a fortified lyricism ; more of a driving flow than flowery drivel. As if to make things blatantly clear, Negativland reinterprets flow as speed, conveyed by the soaring fuzz-phase effect on the over-distorted guitar chords - a sound that does justice to the term metal, with a metallic quality that doesn't start searing our ears again until post-punk's experimental guitar distortions circa 1978 (Siouxie & The Banshees' The Scream, Public Image Limited's Public Image Ltd, etc.).

Negativland is also a perverse demonstration of how a rock machine (the band working together, generating their sound, running on their own fuel) can shift gears. This track drives along until it suddenly breaks apart into a wall of guitar noise and starts up again in a different tempo, sometimes faster, sometimes slower. It thus recalls the manipulative tactics of live rock bands who `pick it up' and `take it down' to give the audience a sense of something happening. With Neu, though, it's as if the band is itself a machine - something with gears for speed and nothing else, suggesting that all manner of drama, intensity and power are generated through the speed of a rock flow.

Streamlining things even further is the track Sonderangebot which is not much more than long, sustained sheets of noise produced by the slowed-down recordings of crash and ride cymbals being played (and note the automobile terminology of the rock-based drum kit : crash and ride). Here Neu simply use technology to control the shift in dynamics as suggested by one of rock's penultimate sonic textures, the white noise of cymbal sibilance : the sound of all frequencies occurring at once ; the effect of all speeds converging. Sonderangebot's employment of sound effects pictures Neu as a group who graft severed sonic textures onto conveyor belts of rhythm. Sometimes the rhythm is manifest (Hallogallo, Weissensee, Negativland) ; sometimes it is latent or hidden within layerings of rumbling, rattling and rustling sound effects : the cymbals of Sonderangebot; the babbling brook of the dronal Im Glinke; the manic chattering of jackhammers in the introduction of Negativland; or the disembodied, raspy vocal intonations of Lieber Honig.

Their second album Neu 2 (1972/73) is in parts a refinement of the first album, in parts an extension. Refining the lyricism of the previous album's Weissensee is the fairly complex orchestration and instrumentation on Neuschnee. It is structured into a number of distinct sections (all with the one chord) and employs violin, sax and clarinet (or is it fuzz-wah guitar?) plus some delicate lute-sounding guitar work. Extending the gear-shifting on Negativland, Spitzenqualitat simply starts at a decent rocking tempo and then methodically slows down over the duration of the song, until the booming beat of the reverbed drums (the only instrument in the song!) is so slow that it sounds like a series of isolated sonic explosions. Then as the beats get so slow - around 6 seconds between each one - a strange, abstracted, car-like noise fades up, only to be cut off each time the next beat sounds. This gives the song an effect of dying, as if you've been listening to a heart beat or some force which eventually is drained and spent. It's hard to describe because it's probably the most severely minimal song Neu have done. It's also the most minimal rock song you'll ever hear.

Fur Immer is perhaps their definitive statement. All their concerns and stylizations are synthesized into this one long track, translated as 'forever'. It's like a mini road movie, resembling a long and winding trek through various `states' of rock : churning, pulverising, skating, gliding, screeching, climbing, diving - a whole catalogue of movements (ie. sections and shifts) which have an organic sense in their development rather than an applied sense of dramatic deployment. Sticking once again to the one-chord/one-key format but this time with more overlaid textures and new instrumentation (particularly saxes), the dramatic changes that do occur in Fur Immer come from within, demonstrating that the driving rhythm of guitars strumming a single chord contains many levels of intensity which can be engineered without recourse to melodic and harmonic construction (melody line, key change, modulation, verse/chorus, etc.). In this sense, the `flow' in Neu's one-chord drives is an effect of movement implied despite the inertia of the solitary chord, but what might otherwise be given as immobility is here generated as stabilization - not unlike the feeling of speeding along so fast and in such comfort that you think you're standing still.

A new, more conventional direction (though still a long way from any norm) appears on this album with Lilac Angel and Super. Listen to them with their date in mind : 1973. Siding with Faust's Krautrock and Picnic On A Frozen River, and their own Negativland (the song after which the American noise band named themselves), Lilac Angel and Super are among the most driving pre-punk songs I've ever heard - especially Super which is like a cunning pastiche of Gary Glitter's caveman chant Rock'n'Roll Part 2 and is the only Neu song with a key-change! True one-chord wonders which have a presence of neanderthal tone and monolithic proportion. Rumbling bass, pounding 4/4 drums, power chords, indecipherable grumblings - born not from any psychotic suburban garage (affected or inflicted) but from two Germans tampering and twiddling with the sound of rock like chemical engineers and motor mechanics, building their machine in the name of industrial research, but giving us a machine which drives better than many of those built by rock's loudmouthed revheads.

Those essential sonic textures and pure chemical ingredients have been grafted, distilled and combined under laboratory conditions (the recording studio of Conny Plank - co-producer of all their albums) to give us an essence of rock. Not a holistic essence, but one that is clearly displaced and obviously the result of experimentation. All the same, these two tracks rock in the most conventional of ways. As a clear sign of this `white-coat' approach to distilling rock as a motor fuel, the second side of Neu 2 is in fact only these two tracks - Neuschnee and Super - played at a variety of different speeds : 33, 45, 78 and even on a malfunctioning cassette recorder. Some people might want their money back after buying such a record, but this side shows how Neu regard technology : as a means to distort sound and produce noise. The logic itself is streamlined : if Neu are a machine that turns itself on to pump out non-stop rock, their records are like micro-machines which we turn on. Furthermore, Neu realize for us the possibility of our changing the speed of their rock flow by altering the turntable speed (which noise merchant Boyd Rice took one step further with his Pagan Muzak `scratch-loop-record' from 1981, playable at any speed). This view of the `self' as machine is the main thing that separates Neu from most other exponents of krautrock, who view machines as glorious devices for man-machine interfaces. Neu's view is decidedly solipsistic but capable of generating a lot more energy. Their view of themselves as machine is summarized in their third and final album Neu '75 (1975). Harking back to how I outlined The Ventures' production of their sound, Neu's sound is reproduced here in a similar fashion : the Neu machine now turns itself on and turns in on itself, reproducing and regenerating its own sound. While this album is essentially a redistribution of techniques and formulae developed over their first two albums, it nonetheless provides fuel for further developments in the sound of rock as we shall see shortly.

Just as Neu were disbanded after the release of Neu '75, they reformed as La Dusseldorf (named after the city in which they were based) and released their first album that same year, titled (surprise) La Dusseldorf (1975). (Michael Rother continued working with Roedelius, Moebius and Plank in Harmonia, while Klaus Dinger teamed up with his brother Thomas Dinger to form La Dusseldorf. See Chart III.) This first La Dusseldorf album could superficially be described as a soft version of Neu, in that its main focus is on fairly lyrical and evocative arrangements, still with the Neu driving quality, but this time with more elaborate chord structures and key changes. The sound is not unlike Neu mixed with the stylistic preoccupations of early Roxy Music, especially on the two merged tracks which make up side one : Dusseldorf and La Dusseldorf. Side two's merger of two tracks - Silver Cloud and Time - is slightly `tougher' but basically headed in the same direction. They seem to be trying to somehow tap the commercial potential of Kraftwerk's Autobahn (1974) which is strange, because Kraftwerk owe a lot to Neu for that album (the notion of driving, flowing, speeding along, etc.).

The second La Dusseldorf album Viva! (1978) more clearly marks an identity for the group away from Neu. Its most interesting feature lies in its attempt to create a European internationalist sound, fusing Italian, French and German stylizations of rock into a musical E.E.C. melting pot. Tracks like Geld, Rhienita and White Overalls evoke the pop-rock of all three countries at once. On this album the Neu road movie has been redefined as an ariel map, locating and gathering a variety of influences, and working them together by overlaying their pop surfaces onto a rock-based bottom which continues the Neu driving pulse. However, in the sophistication of their musical arrangements, La Dusseldorf ultimately drive themselves away from the aerodynamic capability of Neu's earlier rock drive.

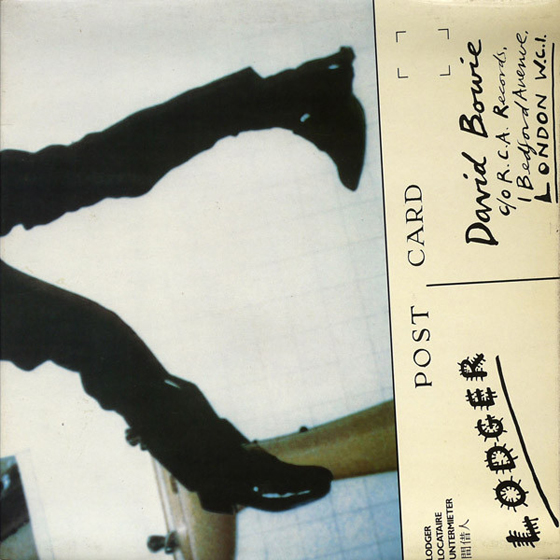

David Bowie: Standing By The Wall

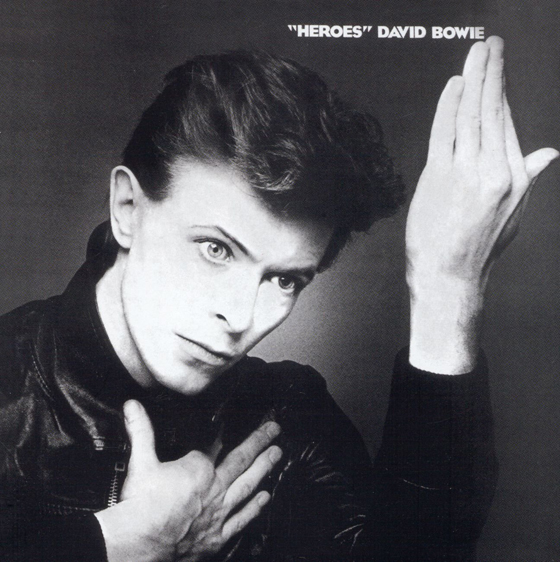

Let's get sidetracked for a moment. Look at the listing of the title track to David Bowie's "Heroes" (1977). Its the only track listed in quotation marks : not Heroes but "Heroes". You're probably saying "so what?" Go back to the track Helden on Neu's third album Neu '75. It's sound and form is the blueprint for Bowie's "Heroes" - cued by the fact that `helden' is German for `heroes'. Further to this, Bowie released the single "Heroes" in French and German, and the German release titled Helden resembles it even more. We're not talking rip-off here, but simply acknowledging the way Bowie has always worked, ie. checking out what's happening around him and synthesizing it. In short, "Heroes" is Bowie playing Neu.

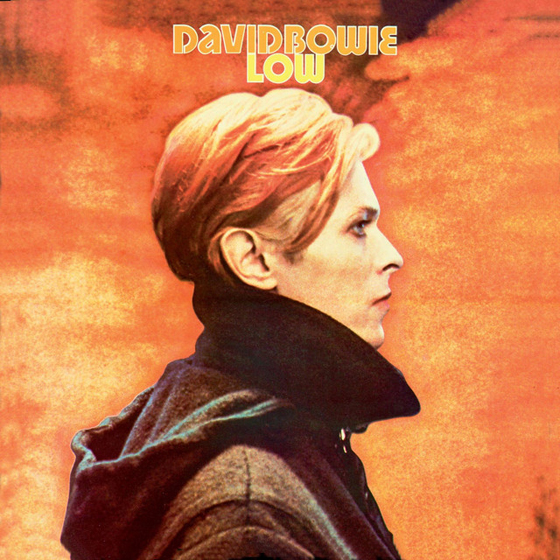

It starts earlier that year when Bowie and Eno migrate to work at the Hansa studios in Berlin "by the wall". Berlin throughout the seventies of course is like a haven for the avant-garde, all centering there because of the `edgy' environment of a city surrounded by `the wall' (the one thing everyone endlessly talks about when you go there). Interestingly, Bowie and Eno soaked up outer West Germany more than Berlin (or to be more precise, Bowie cottoned onto everything that Eno had gleaned from Neu, Faust, Harmonia and Cluster for his first three solo albums - which we'll come to when we cover Eno later). The first album of the Bowie-Eno trilogy Low (1977) is their assimilation of krautrock in general, and the song Warsaza is almost note-for-note taken from Dem Wanderer off Cluster's Sowisoso (1976). The second album in the trilogy Heroes (1977) is probably more directly `Berlin' in tone (harsher, bleaker, etc.) and its title track is basically taken not only from Neu's Helden but also Monza off Harmonia's Deluxe (1975), while the track V 2 Schneider is apparently an open homage to Kraftwerk, and in particular sounds very much like Kraftwerk's Ralf & Florian (1973) where instruments like flute and fuzz guitar are featured throughout. Finally, while Bowie kept to homages, Eno actually struck up a working relationship with Roedelius and Moebius that culminated in the release of Cluster & Eno (1977) and After The Heat (1978) which function as a blue-print for Eno's 1978-onwards ambient sketches for films and airports (leading on to the merger of krautrock with `ambient' music in so-called new age music). (See Chart III.)

This might sound irrelevant to our focus on the sound rock. It isn't. One of the major distinguishing traits on Low is the snare sound which had everyone guessing how it was done. While the credit doesn't lie strictly with either Bowie or Eno (it was producer Tony Visconti who got it by feeding the snare through a harmonizer and dropping the pitch right down), that power-punch snare sound goes right back to Jimmy Page's recording of John Bonham's `garage' drums. While Low was generally treated as Bowie going off on a deliberate and contrived arty edge, the album was saved - rock-wise, at least - by its snare sound, by the explosive sound of its beat. This is important in showing that the Bowie-Eno trilogy (Low and Heroes, 1977, and The Lodger, 1979, plus Bowie's unofficial synthesis of the three on his own with Scary Monsters, 1980) was based on deliberately introducing hard rock stylizations into an otherwise synthetic environment. The latter two albums in particular have some very powerful moments where they soar with speeding rock textures largely the result of Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew (son of Fripp) and their wall-of-fuzz chords, as in the instrumental breaks in tracks like "Heroes", Joe The Lion, and Blackout (all from Heroes) and Boys Keep Swinging, Look Back In Anger and DJ (all from The Lodger). The one feature which ties all these tracks together is that their `instrumental breaks' play like backing: there's no real sense that anything is being overlaid like a solo or whatever. The song's just keep driving along like Neu - not in a similar fashion, but in the way they function.

This Bowie-Eno trilogy ends up being a seminal influence on the electronic arm of the post-punk milieu - Thomas Leer, Robert Rental, The Normal, Cabaret Voltaire, Early Human League and early Ultravox - where Glam Rock and Krautrock are synthesized in exactly the same way Bowie and Eno mixed up electronic alterations with driving guitar sounds. Like all so-called Avant-Garde Rock, we're only ever dealing with 10% Art and 90% Rock (despite what both reactionary purists and arty-farts claim about such work) and proof is to be found in the uneasy yet effective fusions of Bowie's rock stylizations with Eno's studio experiments : their rock sound easily overrides their artistic pretensions.

In The Thick Of Glam Rock

The Bowie-Eno collaboration is not the start of something : it's the end of an era, the final sign of glam rock's life before it is resurrected in the eighties. The glam epoch spawned Bowie and Eno as two extremes of rock stylists, both flirting with art and rock, declaring allegiance to neither. While attracted to each other in terms of surface applications (camp gestures, contrived stances, dilettantish predilections, etc.) and coming from backgrounds in English art colleges, their core perspectives on rock were polarized. As a stylist, Bowie delved into external image production while Eno, as a structuralist, focused on internal image construction. As Bowie restlessly migrated through the stylistic terrains of hard rock, singer-songwriter folk, glam, futuristic concept rock, krautrock, soul, etc. all the time affecting the appropriate stance for each style, Eno took an outwardly experimental approach to playing games with rock composition and production, setting structural processes into motion to see what rock style and form would eventuate. Over a decade later, their positions are similarly separated : Bowie residing in his `real me' space, and Eno inhabiting his sound art laboratory. Their collaboration for the Low/Heroes/Lodger trilogy bears little relationship to their current concerns, and in this sense it marked an end to their glam phases ; a cancellation of their art trajectories, where structure (Eno) and style (Bowie) imploded.

Those trajectories come from a peculiarly British milieu, specifically born from art school preoccupations, where art and rock were and still are confused in complex and interesting ways. British rock and pop generally lean toward detail, organization and surface, producing music that deliberately displays a penchant for polish and a savouring of flavour. This is yet another discourse on the sound of rock - another way of listening to and reproducing that sound, especially in regard to British rock and pop's lineage of affectation. If this approach to the sound of rock is typically British, then the definitive British statement here is glam rock, where rock'n'roll isn't simply copied, but de-historicized : treated as an image torn from some obscure magazine found in a second-hand store. That image is perceived as something that can be copied by reinterpreting its form and content (its cultural and musicological weight) as structure and style - as musical shape and sonic image. Something that can be built and imitated ; remade and remodelled. Such a modus operandi perfectly fits the seminal art college band, Roxy Music - a method they openly claim in their first album's opening track Remake Remodel. Their first two albums Roxy Music (1971) and For Your Pleasure (1972) employ this method and strike a perfect balance between sacrilege (toward rock'n'roll) and seriousness (in affectation). As prime examples of glam, their unrooted sound uses the structural shape of rock'n'roll essentially as a means to display a stylistic image of rock'n'roll, leaving us with a curious paradox typical of glam : there is nothing rock'n'roll about Roxy Music's early work, yet none of it could have happened without the rock'n'roll which preceded it.

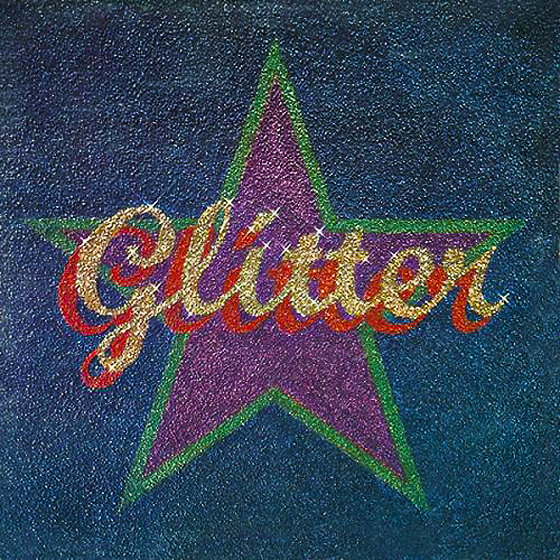

But let's get definitive : Gary Glitter. Take Rock'N'Roll Part 2 (1972) - the instrumental flip side of his first `double A side' single - and survey it in terms of how it treats rock'n'roll in a similar fashion. Mike Leander's production on the song is extremely important in sculpting a sound that is at once a distant echo (the fifties'-style delay effects on everything) and an immediate presence (the chunkiness of the brass chorus, thumping snares and guitar unisons). That distance and closeness is also a perfect metaphor for glam's fix on rock'n'roll : perceiving it as something long gone and only capable of a present evocation through extreme distortion. Like the bulk of both Roxy Music's first two albums and Gary Glitter's first two (Glitter, 1972, and Do You Wanna Touch?, 1973), the anthemic seventies' call-sign Rock'N'Roll Part 2 treats rock'n'roll as `classic' - a kitsch perspective similar to that which gives us Statue Of David candles, Acropolis car-ports and Mona Lisa tea towels. The classic reduced to the plastic through a pure application of historical icons. Bypassing artistic purity and sanctity, glam rock opposes essence with thickness, giving us the sound of rock in terms of mass and volume, as if an unsightly three-dimensional construct has been formed out of that image torn from a magazine. The image gains illusionistic depth ; the sound is artificially revived. Second degree rock'n'roll - rock in the seventies.

Everything is thickened in Rock'N'Roll Part 2: from Leander's take on Spector's technique of double-tracking each instrument, to the height of the Glitter Band's futuristic-rocker platform shoes, to the bulk of Gary Glitter's gastronomic garth. Glitter and Leander defined glam's sound production as a process of thickening rock'n'roll, as distinct from Led Zeppelin's solidification of the blues and hardening of rock. The `thickness' of the Glitter/Leander sound is the result of multiple applications of image : first parring down structure to an image level (down to the well-worn and easily produced iconic traits of classic, fifties rock'n'roll formulae) and then overlaying it with literal and visceral imagery and style (as a take on the glamourization of rock'n'roll once it was accepted and refined by the entertainment industry - all its glitz, pizzazz, showmanship, showiness, costumery, etc.). Consequently, with all its neanderthal corn, moronic power and burlesque staging, Rock'N'Roll Part 2 is a meeting between structure and style that stands as a key image for many of the structuralists and stylists who comprise the glam epoch and who treat the sound of rock in this fashion.

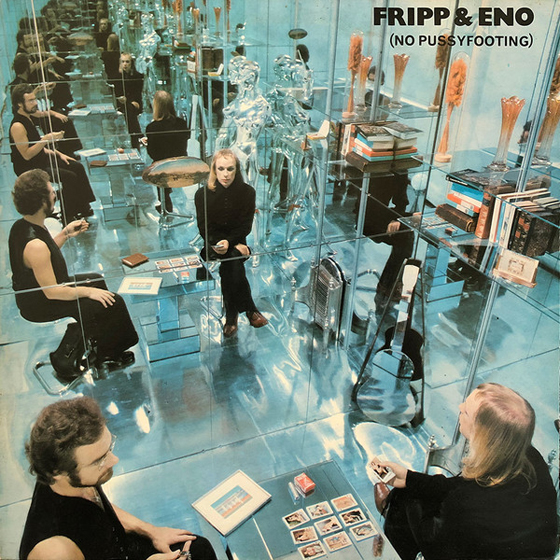

Fripp & Eno: Texture & Process

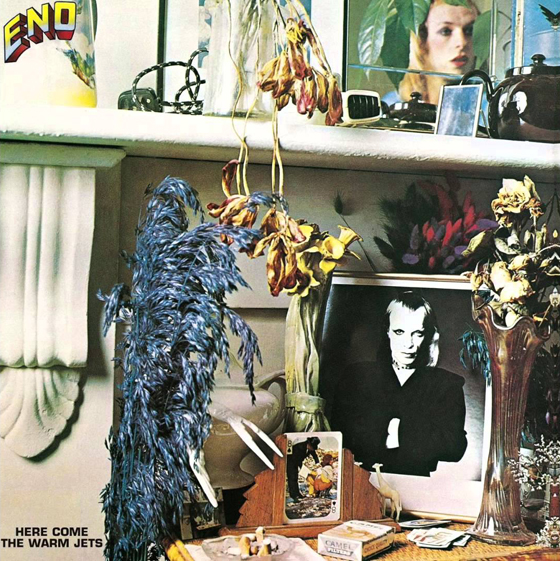

Bowie made a lot of noise about how rock/rock'n'roll was just a style for him to pick up and play with. But listening back to his peak glam period (1972-1974) it hardly conveys any sonic sensibilities attuned to the sound of rock (save for Mick Ronson's guitar style and Tony Visconti's production technique). His music sounds his own, carrying the Bowie stamp of chameleon identity and having little to do with the historical lines of rock sound we have covered in this article. Eno, on the other hand, generally made a point about rock being a means to an end, a way of experimenting with the studio console as an instrument, as something that could be tampered with and laterally explored. Listening back to his work now (from 1973-1974) I can't hear much of his sound art philosophizing - but I can hear some incredible rock music. As things measure up now, he achieved what Bowie professed (ie. making rock not by playing it but by playing with it) yet Eno himself always seemed to half deny that it was rock that primarily shaped his approach to sound, and not the dada artists, experimental musicians and electronic composers he often cited, paraphrased and appropriated.

A good example of this contradiction lies in his work with Roxy Music - in particular, his solo synthesizer breaks on Remake Remodel (from Roxy Music) and Editions Of You (from For Your Pleasure). Superficially, those solos are gestural : they signify the amateur non-musician making noise by aping the theatrical dynamics of a traditionally skilled solo, doing so by maniacally twiddling knobs on that great `non-instrument' and enemy of rock'n'roll, the synthesizer. That, if you like, is their shock value. But in regards to their sound, they simply continue to develop the guitar solo which by the end of the sixties had truly degenerated into noise, with the advent of fuzz, wah-wah, distortion and feedback. What was intended as a gesture became a legitimate contribution of sound. Perhaps Eno stumbled onto this. Whatever the case, he eventually accepted that those `gestural' solos had a sonic function, and that his role in producing such sounds lay in his treatment of them.

Eno's first album Here Come The Warm Jets (1973) is his treatise on treatment. While it stylistically carries the prerequisite stylistic traits of its era (thickened rock'n'roll, camp affectations, decadent imagery, cute lyrics, etc.) its sound production withholds some potent reworkings of rock sound. A clear influence on this album (as on all of Leander's production work) is Phil Spector : the prime sixties pop figure who dealt with rock in the most artificial way imaginable. Via his treatments of every instrument on the record, Eno transforms Spector's infamous `wall of sound' into a wall of noise. In some cases the reference to Spector is unmistakable : Needle In The Camel's Eye, On Some Faraway Beach and the title track Here Come The Warm Jets. All these songs evoke the wishy-washy swelling of the Philadelphia sound, but under terms of total distortion, with perhaps the title track being the clearest demonstration of consigning the vocal presence to the background as a hovering texture prevented from occupying the front spotlight.

Running parallel to such stylistic treatments are the incidents of pure, unadulterated noise which cut into the album in every possible location. Listen to the Davie Allen fuzz sound once again sent into overdrive as it soars throughout the background of the lush, tongue-in-cheek ballad Cindy Tells Me; the destructive, funky chords which trail out during the ending of Blank Frank and the equally funky guitar strumming which maligns its degenerated Bo Diddley riff; and the cut up sheets of noise which exaggerate a thumping heavy metal rhythm in the segue which ties together Dead Finks Don't Talk and Some Of Them Are Old. Finally, there's the central guitar solos on songs like Driving Me Backwards, Blank Frank and Baby's On Fire - all performed by Robert Fripp. These solos realize the sonic potential indicated in Eno's synthesizer solos in Roxy Music, this time replacing the synthesizer's gestural status with the guitar's distorted gestures. It's not simply that the guitar sound is transformed into noise by Eno's treatment, but that Fripp's guitar technique and style seem to be responding directly to the treatment, writhing and wretching as if he is feeling the total effect of Eno's sonic doctoring.

There's something sublime about the working marriage of Eno's treatments of Fripp's guitar playing, because together they generate a unique production of rock sound which neither were capable of alone. It starts with their first official collaboration on the Fripp & Eno album No Pussyfooting (1973). Misperceived at the time as both an indulgent meeting between two dilettantes succumbing to krautrock's growing influence on English art rock, and unrecognized for its take on the then-established success of minimalism (particularly Terry Riley) in new musical circles, its main concern was to experiment in combining texture (Fripp's guitar) with process (Eno's loops) to streamline a rock sound into a stretched-out, linear essence. Such a meeting obviously grew out of certain attractions between the two artists as demonstrated by their previous work. Fripp's guitar sound was already established in King Crimson, where he took all the distortion and harshness of the last decade of guitar noise and smoothed it out into the paradoxically mellow, rounded and dulcify tones of extreme fuzz and feedback effects. Eno's track record of treatment, distortion and experimentation within Roxy Music although not as readily admired was nonetheless there for those who cared to listen. Somehow they got together (possibly through Roxy Music and King Crimson both recording on Island) to produce the essential take on the sound of rock.

That sound is on their two collaborative albums. No Pussyfooting was perhaps di serviced by its camp gesticulation - from the tackiness of the all-mirror room in which they pose on the cover, to the titles of the tracks (The Heavenly Music Corporation and Swastika Girls), to their declared shared interest in collecting pornography and eroticism. Still the music has a quality quite removed from its image problems. Their second album Evening Star (1975) probably achieves its exploratory aims in greater detail and with more sophistication. Side one is devoted to the proto-ambient, semi-hypnotic stylings of tracks titled Wind On Water, Evening Star, Evensong and Wind On Wind. Their lush, evocative quality is counteracted by the one track which makes up side two An Index Of Metals. This track is their definitive statement, not simply because it avoids their otherwise drippy version of minimalist layering on other tracks, but because it presents the essential sonic texture of rock as an endlessly soaring fuzz guitar, feeding back into infinity, looping its own distortion onto itself in a dimension devoid of rhythm save for the relentlessness of its repetitive fragments. This is what Fripp and Eno collaboratively posit as their sound of rock.

In between the two Fripp & Eno albums, King Crimson - under the direction of Fripp and possibly under the influence of ideas which grew out of his collaboration with Eno - recorded two important rock albums : Starless & Bible Black and Red (both 1974). King Crimson have always occupied a strange position in English progressive rock throughout the seventies, being neither a straight rock band nor an overtly symphonic rock ensemble. If it weren't for Fripp's `post-rock' guitar distortions, they could have more easily accepted their occasional jazz rock pigeon hole, but Fripp - as the group's mentor - always guided them as a rock band, as a unit dealing with how rock could sound, even though their stylistic extremeties seemed to often go outside of a rock domain. Coming at the end of their first working phase (they disbanded in 1975 and reformed in 1981) Starless & Bible Black and Red comprise their best work.

Fripp's epicentral view on rock is to be found in the track Fracture from Starless & Bible Black. A twelve minute rambling discourse on rock form and structure, it is the sophisticated finalization of his fracturing of rock-based scales, modals and progressions which he instigated with the perverted 12 bar riff of their first hit 21st Century Schizoid Man (1969). The sophistication of Fracture lies in how far it realigns the `bar shifting' forms of blues rock, here serializing a riff by playing it in a seemingly endless variety of keys. Each key change is thus a fracture in that no one occurrence of the riff is presented as either the right one or in the base key. The key to Fracture is neither here nor there, and can be found only in the breaking and shifting between keys. To top this off, Fracture features some of Fripp's most severe rock-styled guitar distortions, with sheets of fuzz and feedback which (especially in the second half of the song) carve into the shifting structural demarcations of the song's rhythmic formations.

Their next album Red (recorded that same year) is their final testimony to hard rock. It signals their return to a basic unit of drums, bass and guitar, cued by the cover's take on The Beatles' first album cover, with the band member's faces half-lit in black and white. But this return to basics is triggered under intense conditions, where the trio perform to their limits : from Fripp's slamming sheets of guitar noise and distilled, heavy metal chord riffs ; to John Wetton funking his bass so hard it fuzzes ; to the popping, jazz rock sound of Bill Bruford's snare bashing. These combined intensities give us the meshing and melding of this album's rock sound, where everything is compressed, where everything - like the back cover image of a speed or pressure gauge - is sent figuratively and sonically into the red. The rock machine on the verge of self destruction.

Bruford's jazz drumming is perhaps what gives this album a jazz rock intonation, prefiguring the hard rock/jazz fusion six years later with bands like Material, Massacre and The Decoding Society. However if John Bonham had done the drumming on this album, we would have had a hypothetical extension of Jimmy Page's approach to hard rock - meaning that the drums here sound jazz rock, but the guitar work is an unmistakable mix of heavy metal and hard rock. Listen to the instrumental title track Red and hear how closely it verges on the moronic chord-riffing of Black Sabbath, yet is saved from doing so because of the fuzz bass swimming underneath, the percussive cymbal embellishments circling around the riff, and Fripp's spiralling modulation of the riff, shifting it up, down and sideways as in Fracture. This stylized mix of extreme heaviness with open-ended progressions is also featured on One More Red Nightmare, especially in its climactic, instrumental second half where the bass guitar fuzz starts breaking apart almost as much as Fripp's scraping screeches - some of which are so noisy they sound more like amplifier crackling then guitar manipulation.

Closing the connection between these two albums is the final track Starless. It starts off with a soft vocal section, but then moves into a series of progressions which synthesize the shifting of Fracture, the heaviness of Red, and the harsh funkiness of One More Red Nightmare. Listen to the tense build up during the first movement of the second half, where the bass plays the core riff, modulating it through a number of key changes, while Fripp plays single notes over each set of modulations. As each cycle of serialized modulations is repeated, Fripp calmly moves up one or two frets on the guitar, still plucking only a single note. The method is simple but extremely effective. Logically, the song keeps on building up, rising and rising until Fripp is playing his single note right up the top of the guitar neck, at which point he starts bending the strings, causing them to wail and scream under this tension. Finally the song erupts into a full-bore rock drive, as if they've broken the sound barrier and moved into a hyperspace of guitar noise where Fripp performs one his most elaborate noise solos ever.

This `breaking of the sound barrier' effect on Starless works as a good metaphor for how Fripp formulates his own guitar sensibility. His playing is always based on compression - on reaching extremes through a compressed method of technical execution, by playing too fast (as in King Crimson's earlier techno flashes) or too slow (as in his work with Eno). His intensities thus shift from complexity to simplicity, always controlled by an extreme sense of self discipline. The rock which results from his guitar method thus works in similar ways - from the sonic overkill of Red to the creeping tension of Evening Star. Fripp eventually developed a solid philosophical framework to support his guitar method which he titled `Frippertronics' (as figured on his solo `Frippertronic' albums recorded live on tours in Europe and America, God Save The Queen, 1980, and Let The Power Fall, 1981). `Frippertronics' was based on the minimalist notion of creating more by presenting less, and Fripp delighted in being renowned as one of the fastest and most technically competent guitarists who had `reverted' to playing only one or two notes at a time for his `solos'. These occasional notes of course were fed into the modified and linked Revox tape decks which generated the multiple delays which he could build up into a wall of guitar sound - an aural architecture sculpted entirely from guitar textures.

All this ground covered by Fripp and Eno - both together and alone - constitute a defined corpus of ideas and techniques which Bowie bought wholesale through his collaboration with Eno for Heroes (Fripp & Eno), The Lodger (Eno & Belew) and Scary Monsters (Fripp) where the Fripp/Eno connection of texture and process provide the backbone for the sound of those albums. Let's close up this connection by returning to Eno - to his second solo album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) (1974). Fripp doesn't appear on it (possibly tied up with the two King Crimson albums recorded that same year) but just as Red is King Crimson's hypothesis of hard rock, Eno's Taking Tiger Mountain is his final and most incisive commentary on rock before he starts edging more and more into his arty ambient preoccupations.

As such, this album is possibly the first properly postmodernist rock album (predating the overtly self-conscious postmodernism of later works like The Flying Lizards' `anti-production' album The Flying Lizards, 1979, and Bowie's `anti-song' album Scary Monsters, 1980, both of which actually employ modernist devices and tactics initially designed by Eno). I tag Taking Tiger Mountain `postmodernist' simply because this album sees Eno surveying all the modernist tamperings with rock which preceded him (glam, hard, heavy, kraut, techno, etc.) and then realizing that `rock' had by 1974 virtually ceased to exist in any recognizable form, state or status : rock had become merely the suffix of whatever measures people wanted to take (glam rock, hard rock, etc.). Eno's processes, tricks, games, experiments and treatments (which are more sophisticated on this album than on Here Come The Warm Jets) acknowledge this displaced and discontinued state of rock, and thus concentrate on rock operations ranging from the plastic to the perverse.

`From the plastic to the perverse'. What am I saying here? Go back to Faust and their collaged fragmentation of rock, where they cut up rock in every way possible by performing a range of operations on it, creating weird, Frankensteinian assemblages which jerked and moved in strange ways. Well, Eno (on his second album) takes all those types of fragments and puts them back together so that (a) you don't necessarily notice their outright weirdness, and (b) the finished, collaged forms almost appear conventional, giving us a homogenization of heterogeneous parts - a hallmark of postmodernist strategies. His first album veered toward this with its overt distortions of Spector's plastic sensibility of treating rock and pop norms purely as material to be handled and assembled. Eno (with the aid of Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera who served as assistant producer and co-arranger on this second album) takes this to its logical conclusion by perversely re-treating those plastic processes, taking them full circle back to seemingly-conventional songs.

Three directions are clearly marked on Taking Tiger Strategy: the art naive/dilettante/dandy stance of the ironic cute'n'corn in Burning Airlines Give You So Much More, Back In Judy's Jungle and Put A Straw Under Baby ; the neo-primitive/atmospheric/multi-textured layerings of The Fat Lady Of Limbourg, The Great Pretender and Taking Tiger Mountain; and the rock explorations of Mother Whale Eyeless, Third Uncle, True Wheel and China My China. This final section of rock explorations is most directly related to Eno's postmodernist angle on the sound that rock makes once it has been pumped up and flattened out by the brash stylizations of the glam epoch.

True Wheel is one of Eno's best pop/rock songs. It contains his definitive `one-note-solo' - many prototypes of which appear on Here Come The Warm Jets. It reaches a refined peak on True Wheel when it bursts out in the break of the song and then ironically develops a one-note harmony which then carries on into the next section of the song : the solo highlighted, then the solo backgrounded. As a structural gesture, this song posits the solo simply as anything that is put into the place where you expect a solo to be, prefiguring the developments all solos would start to take throughout the eighties : solo by name alone. This `syntactical' play (structuring things in accordance with or against your expectations) is also present in the three chord sequence played over the four chord melodic phrasing, continually but subtly throwing the verse/chorus structure in and out of phase. The illusion is that it sounds right - but structurally it's all wrong. Another paradox typical of glam's deliberate playfullness.

China My China is perhaps even more perverse than True Wheel. Apart from the song's harsh atonality and massacred reggae rhythms, it presents a highly self-reflexive take, once again, on the function of the solo. The verse just prior to the solo intones : "These porters they are such fun. They know just what their fingers are for : to play percussion over solos." Right on cue, the rhythmic tapping of typewriter keys appears, one in each speaker, while Phil Manzanera perform's a very alien-sounding solo. At that point you realize how the solo is being executed: he has placed the guitar's bottom string right next to its top string, so that as he plays across both strings, the guitar jumps from very deep notes to extremely high notes. The left-right separation of the typewriter rhythms is thus extended (under purely perverse terms and for no technical reason) to the bottom-top separation of the retuned guitar strings. The point is that whatever form and structure this song has is illusory and phantom, because it is based on a conjected and invented foundation resulting from Eno's post-Cage experimentation with arbitrary connections. Typical of postmodernist formation, True Wheel invents itself. Eno developed this further with Bowie during the recording of Adrian Belew's guitar solo on Boys Keep Swinging by recording a number of solos and mixing between them to accent their fractured `anti-narrative' development. Fripp, meanwhile, single-handedly provides the final word on the matter with his solo for Bowie's It's No Game on Scary Monsters. In this song the `solo' is played totally against the whole song's form and development - that is, continually, whether it be during the verse, chorus or actual solo section. A definitive statement instigated by Eno's enquiry into the syntactical breakdown of the rock/pop song's conventional narrative shape and form.

Finally, Third Uncle. This song is another one of those unsuspected pre-punk songs from the early seventies. It has all the traits of others like Neu's Super and Lilac Angel and Gary Glitter's Rock'N'Roll Part 2 : a driving beat of only one or two chords (maximum) carrying incomprehensible lyrics. In Third Uncle this premise is further treated and modified. Listen to : the dual guitars frantically strumming, one in each speaker (picked up later by The Buzzcocks and The Feelies) ; the way the bass guitar starts deliberately playing the wrong note in the third chorus (producing a tonality not unlike the off-key appeal of early Cure, Banshees, Wire, etc.) ; and the severe treatment of Manzanera's guitar solo which thrashes wildly in the throws of its own decay and destruction (a guitar sound that also crops up on the incredible Eno-treated Manzanera solo on John Cale's Gun, 1974, and which later became prominent in many post-punk developments).

After Taking Tiger Mountain Eno noticeably shifts into more clearly prescribed areas of artistic experimentation. His only other solo contributions to rock sound after 1974 are the track Skysaw on Another Green World (1975) and the raunchily remixed King's Lead Hat single taken from Before And After Science (1977). Interestingly, these two tracks obliquely lead us back to Neu and Faust, whom we must by now acknowledge as prime, unsung influences on Eno's approach to rock. Skysaw is a virtual recreation of Neu's guitar fuzz-phase on their Negativland, and thus is perhaps influential by default upon post-punk guitar effects. As for the Faust connection, compare the 4 prints enclosed in Before And After Science with the prints enclosed in Faust's So Far. In 1977, though, this was perceived as Eno's deliberate declaration of artiness in the middle of punk's anti-art sloganeering. Equally deliberated is King's Lead Hat's sideways glance at punk's freneticism, which stands almost as a remake of Eno's own proto-punk Third Uncle, almost as if he is reminding the new generation of art students of their shared glam legacy.

To an extent at the time, British punk acknowledged this `shared glam legacy'. While Bauhaus' cover version of Third Uncle on the flipside to their Ziggy Stardust single (1982) is fairly flat and predictably `thrashed-up' in goth-punk fashion, it did serve to further indicate British punk's glam debt - from Eater covering Queen Bitch and I'm Waiting For My Man (1978) to The Wasps also covering I'm Waiting For My Man (1978) to The Damned covering Ballroom Blitz (1979) to The Human League covering Rock'N'Roll Part 1 (1980) to Bauhaus covering Telegram Sam (1980) and Ziggy Stardust (1982). But hang on - all this from Third Uncle? No, but as a quintessential synthesis of glam's self-reflexivity, its attitude toward sound was reverberated - knowingly or not - in a post-glam generation to such an extent that it almost appears seminal. Listen to early first wave punk which grew up on glam and you can't actually hear it in their overly deliberated `punk' sound. Listen to Third Uncle now and you can hear all the arty impulses which pushed post-punk explorations out of the punk explosion. Such is the movement of the sound of rock : lateral, atmospheric, dimensional. Unexplainable in terms of influence or originality ; accountable only to the haphazard conditions which shape historical and cultural developments ; and demonstrable by the music itself.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.