Metropolis

Metropolis

Historical Markers of the Modern Soundtrack

Developed for RMIT Media ArtsGeneral time frames

Silent cinema - 1927 to 1927 ; sound cinema - 1927 onwards. 1927 is historically cited as the dividing point between the two cinemas because of Warner Brothers' release of THE JAZZ SINGER which featured the first occurrence of synchronized dialogue : "You ain't heard nothing yet!" However, various experiments in synchronized dialogue (and music and SFX) layed out the groundwork prior to THE JAZZ SINGER.

Between 1895 and 1913 a variety of technological/mechanical novelties were invented which provided sound accompaniment (usually pre-existing musical recordings on phonograph) to 'peep-show boxes' and the like: the Kineto-Phonograph, the Kinetograph, the Vitagraph, Kinetoscope, Synchroscope, etc. All these inventions, though, apparently didn't have much scope for development due to technical shortcomings and the fact that they mechanically linked two separate recordings (one visual, the other aural) as opposed to recording the one event/action simultaneously as sound and vision. From around 1920 up to 1926, various experiments were conducted with this type of dual-system recording process. In 1926 the Bell Telephone Laboratories perfected a sound-on-disc system which was purchased by Warner Brothers. They used it for THE JAZZ SINGER, however it still involved the projectionist to hook up the disc-recording (via separate playback equipment) to run in synch with the projector. The bulk of the original film did not utilize this synchronized disc system.

Sound in silent films

While there were continual experiments in the technical combining of sound with image via various methods of post-synchronization and dual-system recording processes, the spoken voice was always a part of the so-called silent cinema:

1. 1890 - 1912 : narrators often accompanied the silent images with a spoken monologue that both described what was happening in the film's story and enlivened the screening into a live performance. He was a development from two l9th century forms of entertainment - the ballad singer (who sang tales while pointing out the song's events through a series of sketches or paintings) and the slide-lantern lecturer (who would, literally, present a slide-show and talk about `images of the world' being presented).

2. 1910 - 1915 : various experiments with actors or singers either speaking dialogue or singing verse from behind the film screen. Problems of rhythm and compatibility between the visual/title-card narrative and their spoken/sung narrative curtailed further developments in this area. Some films would be shot with a large amount of visibly-spoken dialogue, so that either behind-screen actors or onstage narrators could lip-synch the dialogue live. This type of shooting method also related to the fact that a lot of audiences - after watching so many films - became quite skilled in lip-reading themselves.

3. After the success of THE JAZZ SINGER it became common practice for the production shoot of a film to allow for the possibility of adding sound later (via the sound-on-disc system controlled in synch with the projector by the projectionist). This was because not all cinemas wanted to or could afford to install the new equipment for playing sound films. Many films between 1927 and 1929 would have then possibly existed in a dual format - able to be played with the sound-on-disc sections or perhaps lip-synced live.

4. Once the marriage of the soundtrack with the image-track was mastered (c.1929 onwards) many silent films then had a new synchronous soundtrack post-dubbed and married to its image-track. This also involved considerable re-editing to remove all the unnecessary title-cards and to reshape the rhythm of the new sound film.

Music in silent films

Music accompaniment was always present in the silent cinema - perhaps even more so than the spoken word, mainly because synchronism was not such a problem in terms of timing background music with the screen's images:

1. Dramatic scenarios

Music would perform a mood/commentary/thematic function, supporting the dramatic flows of the film. This area developed with the various ways in which orchestras and organs could accompany the film:

(a) live orchestras, sometimes with special scores composed for the film, sometimes with a selection of classical & romantic excerpts strung out along the narrative; different screenings of the one film could have many musical versions according to the taste of the conductor/orchestrator;

(b) smaller ensembles, combos or chamber orchestras doing the same;

(c) sometimes live singers would be involved in either the orchestra or ensemble; this was a development from the theatrical aspect of the screening where a singer would perform a song or two as support for the film;

(d) large pipe organs (Wurlitzers, etc.) played by a professional organist who also selected the pieces to be played and arranged them in his/her own narrative sequence; the music was a mix of classical/romantic excerpts and current popular tunes; the Tin Pan Alley era (c. 1915 - 1918) was at its height during the phenomenal rise of the silent cinema, so popular music was a strong element in these organ accompaniments which used the same sheet music which people bought to play at home on their own pianos;

(e) pianolas replaced the live organist in smaller theatres; these were manually operated by labour who simply had to keep the pumps going and change the rolls; once again, musical selection was up to the theatre management, so no two screenings might have had the same musical accompaniment.

2. Musical scenarios

Music (through songs, numbers and routines) would be the form of the narrative (as opposed to supporting it): dialogue would be sung, events would be choreographed, etc. Origins here are the Broadway musical, plus other theatrical entertainments like vaudeville and burlesque. This type of musical entertainment could not really be translated into film until the advent of synchronized sound. Note, then, how musicals made up the bulk of early sound films due to their total reliance on synchronism which allowed the genre to fully exploit the `novelty' and advertise its films as "All Talking! All Singing! All Dancing!".

The language of sound film

Cinematic language in the sound film is, of course, dependent on the fusion of the image with its sound. Each though has a different background in terms of their semantic, linguistic and material development.

1. Image

Whereas technically the image is linked to the photographic medium its status in film as a grammatical component relates to the theatre:

(a) early silent film reproduced the proscenium arch of the theatrical stage, giving the camera the function of the invisible 4th wall

(b) montage then afforded film something that theatre was incapable of - the sequential isolation of spatial elements through time as a method of deconstructing/reconstructing a spatio-temporal event

2. Sound

Theatre also gives us the semiotic effects which sound film to this day largely retains:

(a) off-stage SFX : representational (eg. metal sheet; = thunder ; coconut halves = horses' hooves ; etc.)

(b) off-stage SFX : symbolic (eg. simulated rooster crow = morning ; etc.)

The advent of commercial/popular radio broadcasting (c.l935 onwards) imported the SFX methods and devices from theatre and expanded them in two ways:

(a) technological developments in microphones and tape recorders expanded the representational potential for SFX through recording and mixing techniques

(b) the radio medium - being only sound - determined explorations in the symbolic role sound could play in the construction of narratives

The sound cinema then (from the late 30s on through the 40s) developed in tandem with radio production, and both were technological and semiotic developments from the language and materials of theatre. In fact the narrative explorations of radio (in terms of how it manipulated sound) were possibly more inventive than the cinema's experiments in constructing narratives based on the fusion of sounds with images.

Close analysis

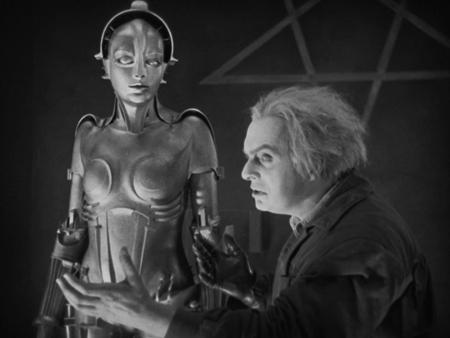

Obviously Moroder's wall-to-wall disco music with AOR rock singers (and their lyrics) changes the original tone and style of Fritz Lang's movie, but as should be evident from details above, silent cinema was a field which rarely cold rely on the notion of an `original version'. Ironically, Moroder attempted at once to put back together METROPOLIS as close to Lang's `original' cut as possible (note the brave declamation at the film's opening) but also to set it to a new score. The ethical considerations of the film makers authorial rights were highlighted by Moroder's project, coming at a time when MTV's fragmented image-narratives, youth commodification and identification, and rock/pop music production were starting to `invade' the cinema (something which many purist critics at the time deplored). Moroder's METROPOLIS simultaneously acknowledged the greatness of past art and re-invented it as a modern faddish event.

Ethical and taste considerations aside, the new version (or should we say `mix'? or quote his credit "reconstructed & adapted by Giorgio Moroder"?) of METROPOLIS affords us a rare opportunity to study the effects of removing one score and totally replacing it with a comparatively alien and dislocating one. Most interesting is the way in which the aural/musical rhythm of the new version is often at odds with the original's visual frame dynamics and its internal editing shape. Below is listed some brief notes on these issues.

1. Crowd scenes on rooftop garden

Note the white-noise synthesized to represent the crowd SFX. There are hardly any `real' SFX in Moroder's mix so as to in effect `musicalize' the whole soundtrack.

2. The factory underground

Note how an introductory montage sets the rhythm for the music track to follow.

3. Light chase of Maria by Rotwrong

Music syncing (key changes, melody introduction & cutting to the beat) cancels out the visual dynamics (symbolism) of Rotwrong's `rape-by-light'.

4. Church scene

Freder awaits Maria : pseudo-church music employed.

5. Maria attacked by Rotwrong while Freder searches city

Same music as `rape-by-light' (musical thematicism) but it goes against the cross-cutting of Freder searching & accidentally coming across Rotwrong's house.

6. Freder banging on Rotwrong's door

Music continues but as soon as the opens door cut to weird synthesizer atmosphere.

7. Rotwrong transforms Robot into Evil Maria

Old style `electrical' SFX employed (like FRANKENSTEIN). When Maria's face finally appears on Robot, musical chord resolves tonality & climax of scene.

8. Evil Maria presented to her master

Painfully literal lyric line ("Here She Comes") in synch with first shot of sexy Maria. Note how the lyrics themselves serve as title-cards which, to an extent, over-explain what is already evident on-screen.

9. Evil Maria in the club Yoshiwara

The new disco score seems to - ironically - match the decor and design of the club, making the scene resemble an actual video clip. Note the echoed and stylized chatter of the club patrons prior to Maria's entrance.

10. 2nd instalment of Evil Maria at club Yoshiwara

Dressed in black she oversees the men fighting for her as Queen sing "Love Kills".

11. Evil Maria preaches in the catacomb

Bonnie Tyler sings "She's The Same - But She's Different" (!); drum burst in synch with crowd surging forward; rhythmic editing every half-bar through to the scene change.

12. Crowd fight Freder & his friend

The following aural/visual connections are made:

slow hum / up-tempo music / cymbal clash end

crowd quiet & ready to fight / fight breaks out / someone stabs Freder's friend

13. Evil Maria incites riot

Main music theme (instrumental) mixed with a soft wall-of-crowd-noise.

14. Evil Maria & crowd destroy power plant

Song: "The Situation's Getting Out Of Hand"; drum-break/pause as Evil Maria switches machine on full.

15. The underground city explodes

Synthetic SFX of explosion, water gushing, crowd noise & warning gong. Note how each explosion is synced on-beat with the main theme running underneath. Quite possibly some of these shots in this very long sequence would have been trimmed or extended to allow the music rhythm to match the editing rhythm so precisely.

16. Water floods the underground city

The main theme is now like a unified sheet of noise/beats covering all edits.

17. The master blacks out

"Age Of Freedom". From this point on the music changes key & moves into melodic developments in synch with the plot. Moroder's score here perfectly apes the conventions of the organ-accompaniment typical of silent movies.

18. Crowd burn the Evil Maria

Note only appearance of vocalized words as crowd chant "Burn her!".

19. Freder unites the master with the worker

"When Two Worlds Meet".

Text © Philip Brophy.