Anime At The Speed Of Thought

Anime At The Speed Of Thought

Welcome To Irabu's Office + The Tatami Galaxy

catalogue essay for the DVD release of Welcome To Irabu's Office and The Tatami Galaxy, Siren Visual, Melbourne, 2011Historically, anime proceeds manga. The manga industry exploded in the post-war period of Japan with the akabon (red-book) chapbook productions of which Osamu Tezuka’s New Treasure Island (1947) was the first big success. Tezuka went on to publish a prodigious number of titles, and in the process became instrumental in advancing manga as both a sophisticated story-telling medium and a multi-layered form of visual narration.

Now while many have tried to make links between manga and Western instances of image-based story-telling, there really is no substantial correlation. This is mainly because the Western history of literature and painting – of exciting the imagination through words and images – is one of two separate paths, cleaved from each other by opposed philosophies of expression. In the West, we are familiar with how there’s a word in the English language for every thing that could exist, and – conversely – that a picture is worth a thousand words. At every turn, literature and paintings have focussed their separatist modes to refine their craft as ulterior versions of the other – but rarely do they combine, exchange, share or fuse their powers of description.

In Japan, the opposite has held sway for centuries. From the reductivist ‘anti-verbiage’ of haiku poetry to the nuanced expressivity of calligraphic drawing, word and image contribute to a holistic sensory construction of the real and the imagined. By virtue of its deft intermingling of word and image, manga is one of countless outcomes of this cultural legacy. So when anime is sourced from Japanese novels (as opposed to the dominant source of pre-existing manga), it’s best to approach the outcomes not as if such anime is more ‘literary’, but rather to consider how the interconnections between the novelistic and the animated feed off each other to create new twists on visual story-telling.

Two recent titles provide such an opportunity: Welcome To Irabu’s Office (2009, based on Tomihiko Morimi’s series of short stories K?ch? Buranko, 2003) and The Tatami Galaxy (2010, based on Tomihiko Morimi’s novel Yoj?han Shinwa Taikei, 2004). Both these anime series have been produced for Fuji Television’s Noitamina late-night weekly viewing to gauge the interest in anime not directly linked to mainstream industrial productions of anime and manga and their attendant marketing strategies.

In Welcome To Irabu’s Office, the eponymous Dr. Irabu enforces a crazed therapy of enormous hypodermics, a sexy pink Lolita nurse, and a strange capacity to almost live alongside his patients to supervise their adoption of his impossible instructions. Rendered in three separate personae, Irabu is a shifty yet darkly empowering figure who ‘cures’ by having his patients confront their deepest fears – though only after they have been thoroughly harangued and debilitated. This is typical Japanese voiding of the Self, where one must reach a ground zero of existence in order to fully rebuild oneself. Irabu is thus your worst nightmare of psychiatry, yet he does produce results.

Just as Welcome mocks all molly-coddling sensitivity in addressing patients’ phobias and neuroses, so too does the series flaunt a disregard for the traditional look of anime, as it bears an almost ‘anti-anime’ aesthetic in its visualisation. Gaudy colours, lo-res video freeze-frames, brutish roto-scoping, irreverent compositing, and abrupt live-action inserts assault the viewer in this sardonic view of psychiatry and the social malaises that afflict highly strung Japanese workers from all walks of life. It’s a remarkable video equivalent to the late 70s underground manga style of heta-uma (‘bad/good’, or terribly ugly and unskilled draftsmanship in drawing yet captivating nonetheless).

However it is Welcome’s literary origins that allow it to wilfully avoid the conventions of anime’s ties to the extant visuality of manga. Instead of reshaping the drawn manga character’s visage for a moving iconic figure in anime, Welcome creates its own visual language from scratch. Furthermore, the original short stories employ multiple discursive voices to undercut Japanese social mores and behaviours. The Welcome anime refreshingly retains this complexity by favouring an analysis of characters-in-situations without having to formulate any grand narrative to explain their predicaments.

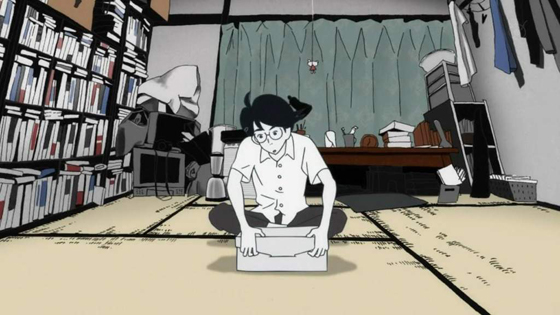

Ironically, a grand narrative is employed in The Tatami Galaxy – but the wild cosmological totality of its original novel’s premise warrants such a tactic. The anime’s 11 episodes track an unnamed protagonist who in his first two years of University enters a sakuru (campus activities club) in pursuit of an enriching social life and the prospect of meeting an adorable true love. Fatally, this never happens. Worse, this student repeatedly undergoes failure and trauma as each episode unfolds in a parallel universe, each one depicting him entering a different sakuru. As the episodes gradually coagulate, they appear to be less parallel dimensions and more confoundingly interconnected scenarios.

Like Welcome To Irabu’s Office, The Tatami Galaxy uses its episodic format to elaborate a scatter-gun critique of interpersonal relationships in contemporary Japan. Tatami’s anonymous hero is cryptically encouraged by the strange senior student-cum-sage Higuchi, destructively manipulated by the comically insidious Ozu, and stupefyingly ignorant of the curt yet supportive Sakashi who tantalizingly remains his true love interest hiding right within his grasp. In each episode this trio of characters repeat their connection with our hero, yet formulate unique possibilities for his attainment of an awareness of his own limitations in realising his own full potential.

The most striking aspect of Tatami is its dense voice-over narration delivered at thrash speed. Rather than reduce the original novel’s narration, Tatami presents an unending stream of hilariously smug diatribes and self-deprecating monologues as we inhabit the vociferous din inside the hero’s insular mind. Notably, director Masaaki Yuasa had directed the seminal Mind Game (2004, from Robin Nishi’s 1995 manga) which forged this compulsive babble of mental miasma into a tsunami-of-consciousness. Tatami goes even further with its dense quips, to which are edited rapid visual flashes. The result is an anime which truly moves at the speed of thought.

Both Welcome To Irabu’s Office and The Tatami Galaxy deal with potentiality as their central theme, frenetically workshopping how the individual can position themselves in the saturated environ of contemporary Japanese life. Derived from appropriately compacted novels while creating distinctive anime story-telling forms, these two titles also suggest that an equally sprawling dimension of potentiality is the gulf that separates Western animation from anime.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.