An interview with Philip Brophy

published in Colour Me Dead, Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2013Interview by Bala Starr

Bala Starr: When we’ve previously talked about Colour Me Dead as an exhibition, I’ve understood that you’re more interested in the works singularly, individually. But there’s an ‘exhibition experience’ here in terms of their installation and integration — these works are three-dimensional and complex in terms of the way we apprehend them. While I know that consideration of the viewer is not part of your thinking during the production of work, can you talk about how you approach ideas about audience experience?

Philip Brophy: I would prefer the term ‘manifestation’ than ‘installation’. A ‘manifestation’ is the material outcome of what starts as a conceptual idea. With the Colour Me Dead exhibition—which features six discrete works—those outcomes are materialised in a shared space to enable you to have an experience and perceive something related to my original idea. ‘Installation’ seems far more whimsical, responsive or egocentric, like a type of artistic practice to evidence an artistic signature. I prefer exhibitions or situations where I’m less conscious of the ‘artist’ and more conscious of the experience of being there. My biggest influence in perceiving installed space this way results from visiting Disneyland in the early 80s, and realising that everything works there because of its complete perceptual control.

BS: Perceptual control of the visitor?

PB: Yes. And specifically the focal delineation between peripheral and focal vision. What was apparent was that the experience of Disneyland was not so much about what you saw: it was about everything that you didn’t need to see. I was flawed by this type of perceptual control. You could see what you were experiencing—but at the same time couldn’t see what you were experiencing. Disneyland is completely faked—but your experience isn’t faked: the ontology of the thing is completely irrelevant. The Colour Me Dead exhibition similarly works with negative space to enforce the ideal vantage point for perceiving the work. Instead of presuming you just wander through the space as if you are actively controlling the experience, I prefer to make sure that you’re conscious of those ideal vantage points. This is why I prefer ‘manifestation’ to ‘installation: Colour Me Dead is a contracted, narrowed experience, not an expanded one.

BS: With your practice there is also nothing else interfering with the experience of the work. There’s a cleaner connection, between you—your body—and the object, so to speak.

PB: Yes, it’s a controlling connection, not a liberating one. When I was thinking where to place the works throughout the gallery, the main question was how do I isolate space to control the interaction. This replicates how I experienced the original paintings in the museums: standing still in the ideal position and contemplating the work. I was acutely aware of the scopic frame and invitational space that these kinds of paintings solicit.

BS: The Illuminated Nymph echoes the neck-craning effect of the Musée d’Orsay, replicating most people’s experience of needing to look up to examine those paintings, but the effect is also so beautiful.

The Illuminated Nymph © 2013 PB: Absolutely. Whereas ‘manifesting’ the work deals with isolating space in the gallery or museum environment and controlling the viewer experience through an ideal vantage point, ‘materialising’ a work involves involves giving it a linguistic form with materials—colour, form, sound, whatever you need. This is something I take from cinema, because films are generated precisely this way. Then once you know what kind of rendering is involved, the process shifts from being material to becoming semiotic. Let’s face it: once you’ve got 300 years of formal crafting and material effects in modes of painting, then the painting techniques constitute a language. I was engaged in reading those paintings in the museum, and my works are thus best read.

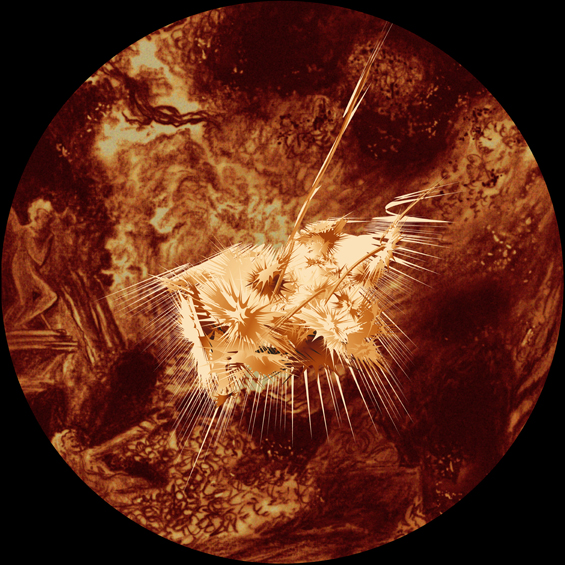

BS: The Illuminated Nymph was an elaborate work to construct, I imagine, because it links back explicitly to many of the works that you were looking at in terms of their original drawing and material processes as much as the cultural image.

PB: The original paintings obsessively made the female flesh as white as possible. With my animations, I’ve extended that to make the flesh so white it destroys itself. It’s like perceiving the original paintings as if they were in a pause mode: all I’ve done is let the pause button go; the white light is so intense it evokes an erasure. That’s its implicit erotic—I’ve given it death appeal.

The Illuminated Nymph © 2013 BS: There are often clear stages in the making of each work—moving from the still drawing to the animated explosion. Can you explain some of these in The Illuminated Nymph?

PB: When I’m doing pencil illustrations and vector manipulations, I’m building new layers and stretching them out, as a means of dynamising and visualising the semiotics of these modes of painting. I’m particularly interested in registering the multiple mythological ways in which I can read a particular visual device. In my mind, the ‘image’ of the body in The Illuminated Nymph is actually being flayed; the flesh is stretched and then pinned on a board. It’s like taxidermy. The Illuminated Nymph also holds the staccato beat of low-grade animation. In this case it’s like a speeded-up effect of what happens when plastic melts and peels in the sun. Or when you see something where the paint has curdled. Each section of the paint separates like a dry mud plane and then the edges curl upwards. My approach to digital animation is not about things magically coming to life under the guise of ultra-realism: I’m showing you how things exist in the post-human realm, so I don’t use any realistic parameter informed by Euclidian physics.

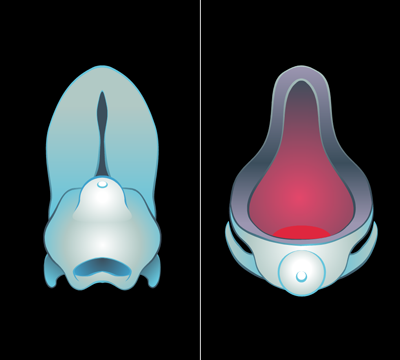

BS: Where The Illuminated Nymph considers a dense range of textural information, historical conditions and links to the present, The Lady in the Lake is a work you’ve described as the one that most literally or didactically unfolds across an art-historical chronology.

The Lady in the Lake © 2013 PB: The nudes in The Lady In The Lake are largely drawn from Symbolist works. It’s amazing how completely out of favour and misunderstood Symbolism is now, because it’s actually the art that became of everything that was before it. Any form of Classicism, any form of Romanticism, logically leads to Symbolism. The Lady In The Lake prints chronologically line up these nudes associated with water, and reads them like a barometric chart to gauge how Symbolism effected this view of the nude body.

BS: Originally you had a different format for The Lady in the Lake, and this configuration really resolved itself only just before installation. Now we are looking at four large landscape-format prints installed under very original lighting that evokes a sense of looking through water. The shallow bands of light that move across the surfaces are barometric lines too?

PB: Every form of visual representation—of charting, illustrating, documenting, registering, gauging—is always about a spectra of energy levels. When I started installing the work, as it began to unfold in front of me, it started to suggest something else. The Lady in the Lake changed because the swirling energy lines and waves that connect the three bodies in each of the four mural prints better served the barometric changes of that subset of nude. The composition changed as well with the vertical figures in the centre flanked by the sideways figures. Once you carry through a visualisation and its manifestation, that allows you to modify and respond to it in different ways.

The Lady in the Lake © 2013 BS: But that does something else too, doesn’t it? Not just for the sake of giving something its own character and identity, but it also says something about your approach as an artist and its stylistic evidence. We have talked about ‘stylistic evidence’ before.

PB: Yes. We are not saying that visual evidence coheres through an identity—as in this is Philip Brophy, this is his sum. I keep responding to the material energy that’s evident in the both the original paintings and my re-versioned works. There is not one nanosecond when I’m looking at a painting and I suddenly revert to some literary model of signification and generation of meaning. For example, with the siren in the centre of the second mural print in The Lady Lake, I’m looking at the speckles on the mermaid’s tail. I’m not meanly thinking of the ‘objectification of women’ or other narrow ideological overlays. For me, every detail in a painting is its own universe. I personally don’t have a problem with visuality being such a complex cosmological mess that you’ll never work it out. The last thing I want to do is reduce it to an ideological after-effect.

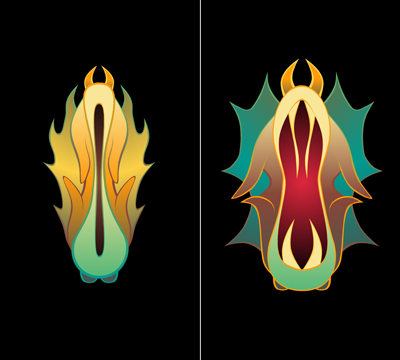

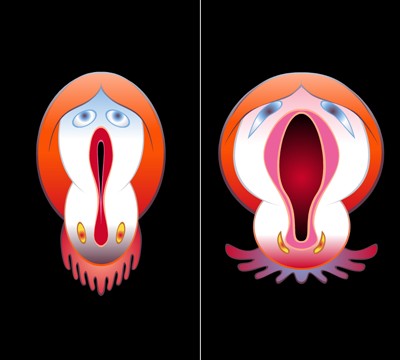

BS: Let’s go to The Hungry Vagina, how did this work come about?

PB: I think The Hungry Vagina is the most elastic abstraction of form out of all the works in Colour Me Dead. You can see on my website the processes of drawing to get those images. It was the means by which I got to the heart of the vagina in each of the paintings. When I look at those original paintings, yes, there’s some other stuff in there, but all I see is a vagina. I think it’s great to look at sexual organs—be they real or illusory. The Hungry Vagina goes beyond the clinical and becomes entertaining and engaging in its own right, because you know you’re looking at vaginas that may and may not be there in the original paintings.

In the 1950s artists like Lee Bontecou (cited in The Hungry Vagina) looked for a cosmological effect in her shift to vaginal abstraction. Artists in Europe were looking to metaphysical ideas and universal primal aspirations—their abstraction was not like American abstraction. To get new value to what they were doing, they looked to the erotics of science. Bontecou’s abstract works are like ‘evaginated’ three-dimensional aircraft. The shapes look like they’re part of metal designs for aircraft or organic machines, with all kinds of rivets and stitches, and all sorts of gaping holes. Studying cosmology like that, I’m sure Bontecou realised the intense multiplicity and contradiction that exists in the forms she worked with. Another The Hungry Vagina artist, Otto Dix, comes from an opposite place, painting hard-on sex pictures as a symbolic space. He was intensely misogynist—but he’s also important due to being so psychologically scarred by his involvement in World War I. If you really want to know how death fucks up someone’s sexuality, go and ask Otto Dix. His often awful paintings grant you that dialogue; by listening to him you can learn a lot about how and why women’s bodies have been progressively visualised through acts of painterly violence.

With The Hungry Vagina I’m not giving you the historical source images directly or definitively. The ambivalence and multiplicity of these images—their ugly beauty—arises from them being images rather than deliberated acts of writing. Images multiply and cancel simultaneously. When I see images, I read everything that they signify—including their contradictory nature, and the way they cancel as well as create.

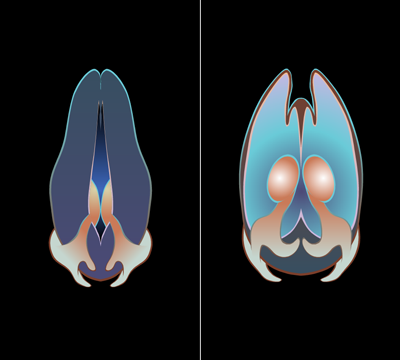

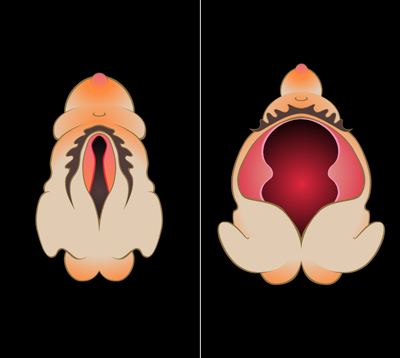

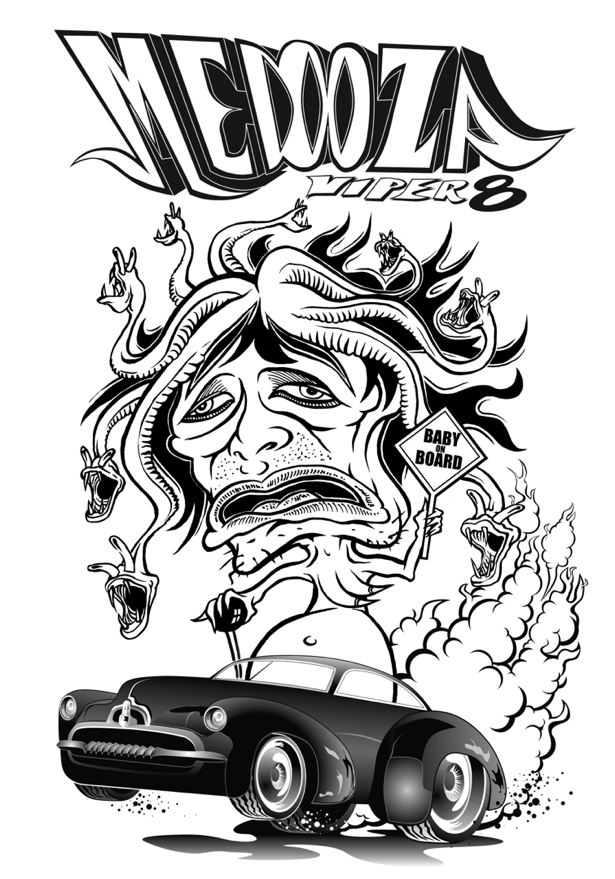

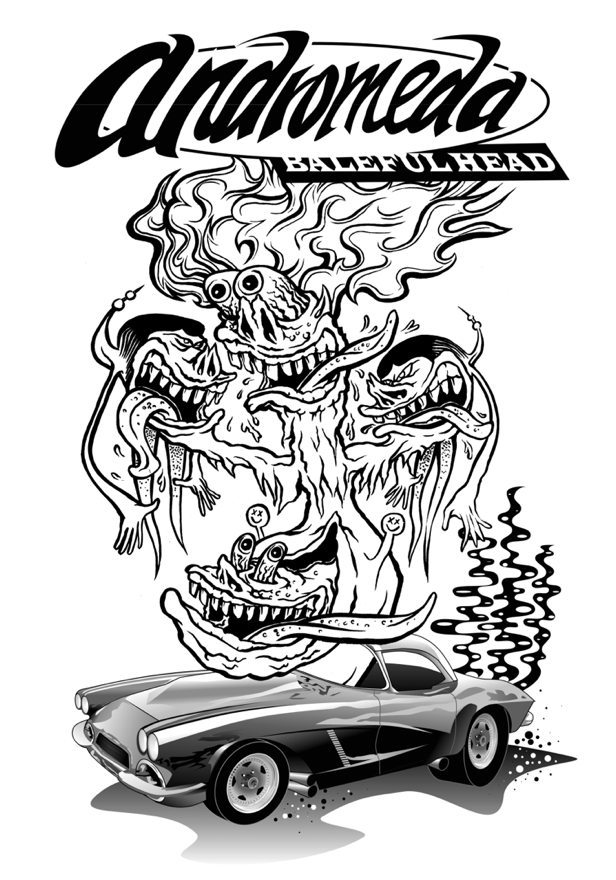

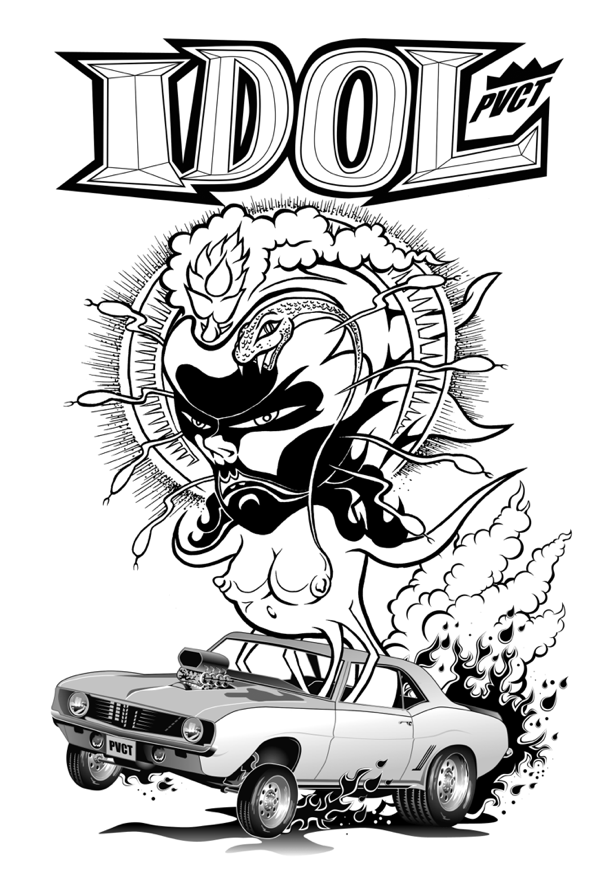

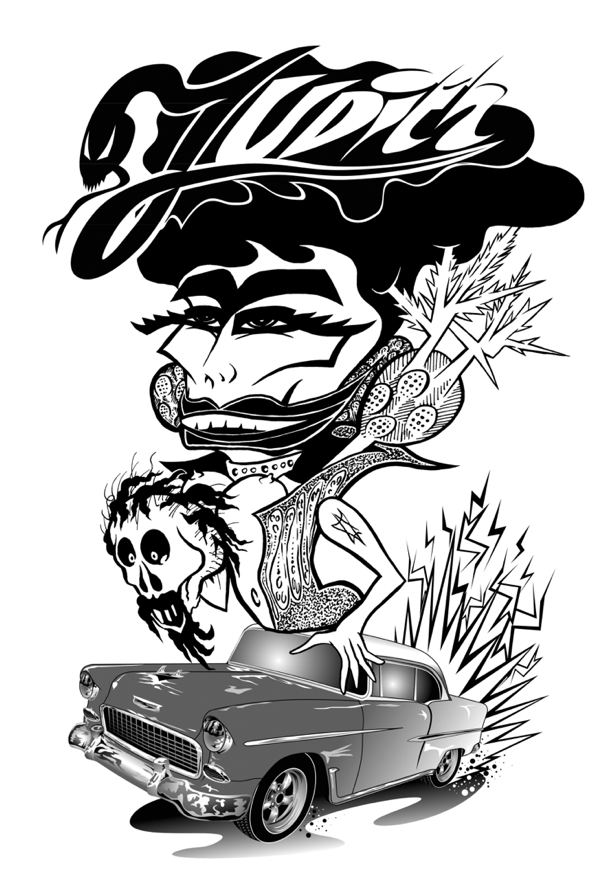

The Sexualized Chimera © 2013 BS: Can we talk specifically now about The Sexualised Chimera?

PB: I like each of my titles to sound like a really good movie! The Sexualized Chimera is about contemporary ‘monstrification’. All the images evoke ‘monster-car’ T-shirt designs from the mid-60s, popularised by illustrators like Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth.

BS: Like Sphinx Nitro?

PB: That one is my take on Franz Stuck’s Sphinx. It’s hysterically vulgar, with vampire teeth as nipples and exhaust flames exiting her buttocks—a regular fire-breathing female monster. This is Symbolist art at its most hysterical, where artworks are trying to sexualise and eroticise, dealing with Eros and Thanatos at the same time, seeking an erotic sublime. The Sexualised Chimera charts where iconography of that kind exists today. I’m looking out my window to see where these modes of paintings live on now—where these vulgar monsters still exist: bong shops and heavy metal album covers. Again, this is keeping with the logic of Colour Me Dead: to evidence what art has become. It was important to work in the mode of illustration. Even the brushwork looks vulgar.

The Sexualized Chimera © 2013 BS: Are these made at scale and than scanned or is there something I am missing?

PB: The original is in pencil, and then I repeat it with Japanese brush and ink. Then I scan that at high res. But the muscle cars are completely vector. Transforming a low-res muscle car picture from the internet into something that completely evokes the sensation of the car being present in the final picture entailed working in painstaking detail.

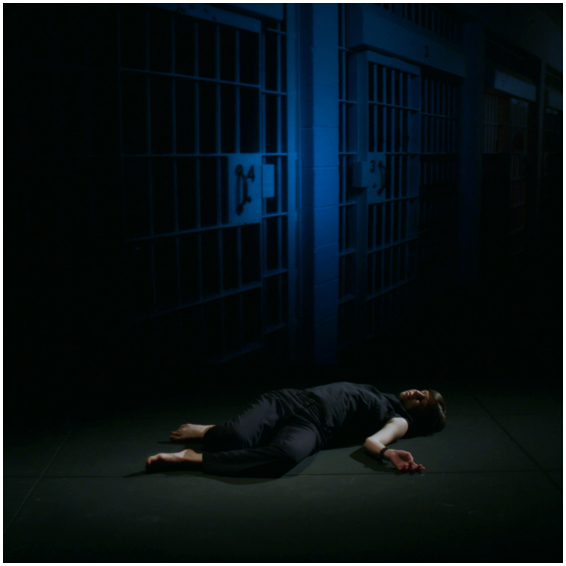

The Prostrate Christ © 2013 BS: Tell us something about The Prostrate Christ. I think it is one of the clearest works. The performers are kind of props; they’re transparent as well, manipulating the artifice of each tableaux vivant.

PB: Actually, that approach to directing the performers comes from working with musicians. I directed the two nude models in The Prostrate Christ not to be puppets being manipulated by the two clothed assistants, but to be completely in control of what they are and how and why they exist. The two figures in black are there to enable that, to get the models into their predetermined pose. Both the two models, Lauren and Charlotte, and the assistants, Kat and Annie, understood this because they’re all professional life models. Their energy is very different from that of an actor, but more akin to a musician.

BS: Their performance is a single unedited shot. The quality of their control is a pretty amazing achievement.

The Prostrate Christ © 2013 PB: Their performance is so absorbing, it passes into a kind of clinical beauty where you don’t even notice that they’re naked bodies. It becomes more about the flow, and how everyone is synchronised to it. Whereas The Illuminated Nymph is stopping the pause button and letting the image play, The Prostrate Christ presents either side of the still image. I felt that sensation of staging and positioning the body when I was at the Gustave Moreau Museum in Paris. The studio in his home is kept intact, and you really get a sense of the light and the air in there; you can feel the theatrical space.

BS: And the square format of The Prostrate Christ?

PB: A simple technical solution to the fact that some of the paintings are vertical and some of them horizontal. It also was the best way of framing the bodies standing up and lying flat.

BS: I’ve been wondering about the way your thinking has developed particularly in the making of The Morbid Forest. Its image structure, using film this time, and it’s obviously set in more contemporary situations. The Morbid Forest is here and now rather than relying on overtly historical references or particular iconographic references. Perhaps it sits within narrower pictorial constraints too.

The Morbid Forest © 2013 PB: There’s two things with The Morbid Forest. The first concerns issues of direction and production associated with filmmaking; the second concerns how The Morbid Forest inhabits a very contemporary social-cultural space.

When it comes to filmmaking, it’s always been apparent to me that cinema has a dramaturgical heart or pulse that comes from dramaturgy. It comes from ideas as simple as, say, a guy with his brother; he kills his brother and then suffers the wrath of the father. Or say, here is a girl whose mother dies when she’s young and then searches for someone to replace her in later years. Dramaturgy is the dynamic DNA of drama—not action. Dramaturgy contains the core elements that impact to make drama. It’s invisible and immaterial, but it’s the fuel for energising a film. Cinema is a chaotic, messy, noisy machine that renders that energy into the real world through images, sound, set designs, illusions, however it needs to. A film is like a tree that has been fertilised by a dramaturgical core. Many people in the film industry think that the seed determines the tree and how it grows; that the seed, the dramaturgical core, is where everything needs to be focused in order for it then to be perfected or idealised. But that’s so wrong: if the seed is a seed, it doesn’t matter whether you water it with Coc-a-Cola or water. Something will happen: it may not be classical or pure; it will be monstrous and transformative. So for The Morbid Forest, I simply set up all the source paintings in a line like a storyboard for a film, then filmed each scene and allowed the ‘narrative’ to sprout of its own accord.

The Morbid Forest © 2013 A key aspect to The Morbid Forest lies in realising how these ‘aggrosexual’ males will not only fuck anything that moves, they will fuck anything that doesn’t move. And consequently they’ll end up fucking themselves, and then they will cosmologically fuck themselves into non-existence. It becomes entropic: that they don’t even know what’s turning them on anymore. This is the model of sexual psychosis and pathology being portrayed in the film.

In the scene of the forest floor, where all the bark is rotting, they just disappeared into it. These guys become scrunched-up cartons and evaporate into a nothingness of rubbish—referencing Hans Arp’s small bronzed Sculpture To Be Lost In The Forest. That’s a positive world-view, I think. It’s not solving other social issues, but it is projecting a way in which that form of sexual pathology runs its course.

BS: Could you explain for us more about the ‘contemporary’ in the film? How you draw this through the scenography?

PB: OK – so this is how The Morbid Forest inhabits a contemporary social-cultural space. Here we are doing an interview, trying to talk over the sound of a helicopter overhead that’s trying to find the handbag of a woman who was raped only 15 metres from where I work in my studio. That incident happened two weeks after the exhibition opened. Right here and now is an example of the messy, noisy, uncontrollable constellation of interconnections between life and art, even as we’re trying to discuss it. Socially-motivated artists tend toward constructing the world as conditional—as what the world should be. I tend towards constructing the world as actual—as how it is despite what I think it should be. So that means there are two worlds which exist outside my window. The Morbid Forest chooses the latter view. When I was contemplating the source paintings in The Morbid Forest, I viewed them through that contemporary perspective, completely registering a type of sexual pathogen which grants the paintings their brooding atmosphere of immanent danger. When the two men stand an survey a sprawling new housing estate in the outer-outer suburbs (referencing Caspar David Freiderick’s Two Men Contemplating The Moon), they see a bounty of potential victims ripe for plucking. That’s certainly not the image promoted on the giant advertising boards in these areas.

The Morbid Forest © 2013 I don’t want to labour over these things, though. Nor am I sensationalising them. But they’re there nonetheless. You choose to see it, or you choose not to see it. I’m not here to change your view. You’ve got to reach those points of view yourself.

BS: The Morbid Forest is hypnotic and mesmerising; the landscape, the light. Is it beautiful for you?

PB: I don’t know how you can call that beautiful, actually. When I think of traumatising experiences of people I know, entailing death, violence and rape and the like, I can’t ‘un-know’ the fact that these are aspects of the world. So rather than bemoan them, once you have been touched by these experiences, you’re bound to see things differently—especially things that for others seem innocent and untainted. Seeing the unseen grants an intensely valuable point of dialogue if you really truly want to make a connection between image culture and society.

BS: Can we turn our discussion again to your thoughts about different contexts and the idea of the ‘museum’? When we first discussed the premise for this exhibition, the context of the art museum itself seemed important. Your website though is sorted into categories like film director, score composer, music performer, etc. But there’s no ‘artist’ there. In fact I remember you saying in one of our earliest conversations that you hadn’t formally shown in art galleries before 2004.

PB: Yes. Colour Me Dead is the most art-centric project I’ve done. It is the most ocular scopic project too—there’s no audio—it’s primarily about visual codes, visual language, reading paintings. And it’s specifically about reading paintings directly, without jumping to connect them to accepted literary, ideological or sociological readings.

BS: In a way there’s the circularity too of going back to the place where you first explored these pictures, from the museum, going out and then back in again.

PB: I probably wouldn’t have come up with this project if the opportunities afforded by both the Mora Foundation in 2009 and Vizard Foundation this year didn’t come forward. So in a sense, the context of galleries and museums helped bring it to life. Nonetheless, I make no differentiation between a major museum or warehouse for doing a performance or project. I don’t make any differentiation between contexts, although the context is always an energising aspect. This itself is not new for me, and goes back to the work with Tsk-Tsk-Tsk. All the projects I produced between ’77 and ’82 deal with putting the one work or project into multiple contexts.

This approach is the inverse of carefully choosing or overly managing contexts—which is how ‘professionals’ in any art form behave. For me, making art is not about empowering your voice as an artist, or ensuring you’ve got a clear line with ‘your’ audience. I've never felt any connection with any audience, mainly because they are never—and hopefully never will be—part of what influences me when I'm making my work.

BS: Now stick to the question!

PB: Going into a museum to me is no different from going into a 7-Eleven. I’m not saying that in a flip way. For me the museum is an interesting experimental site to place Colour Me Dead. But I’m not interested in a segregated professional engagement with the infrastructure and politics that make up the museum, in order to deliver a coarse communication about culture and politics.

I’m interested in the culture that exists in the chaos before people want to make sense of things—before it becomes coded and classified by validated modes of thought. And I’m equally interested in the mass misinterpretation at the other end, where you present work not designed for pre-existing channels. So with Colour Me Dead I’m looking at what those validated channels aren’t tuned to, which is the shift from latent to manifest violence in the depiction of the female nude—about a century before such images proliferate in cinema. My reading of these ‘beautiful paintings’ of the female nude is focused on the lack of contextualization brought to them by their position in the wider, messier, chaotic cultural realm. This is what I mean by dealing with what art has become—not what art should be. I want to come into contact with something that I had no idea was actually there, such as the disturbing darkness in so many of these valorised paintings. The rationalising effects of the academy or the rhetoric of art history do not constitute culture: they are part of its mechanical encoding, it’s white paper politics, it’s conditional utopian view-points of how society should be. Culture is a germ, it’s stuff that happens beyond your control.

BS: Let’s finish there. Thank you. This has been wonderful.

Text © Bala Starr. Images © Philip Brophy.