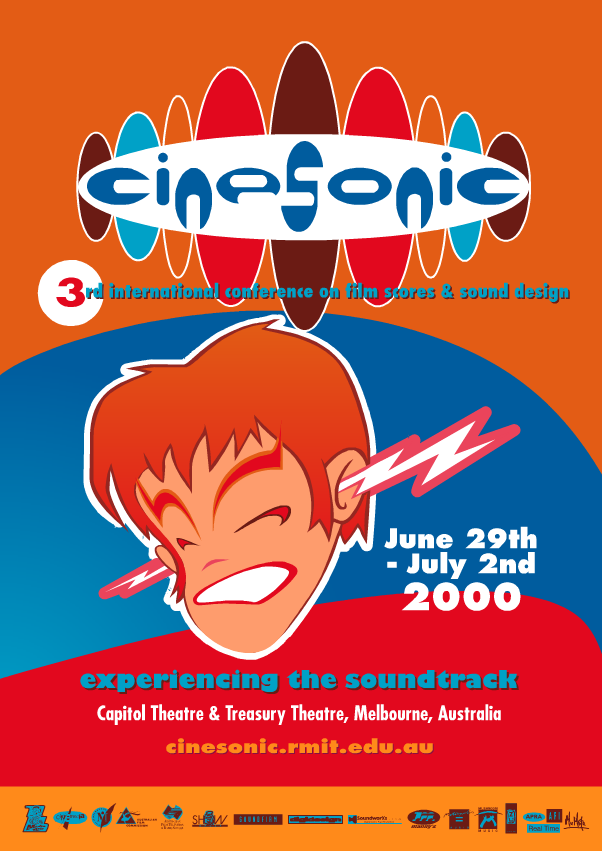

International Conference on Film Scores & Sound Design - 3

Background

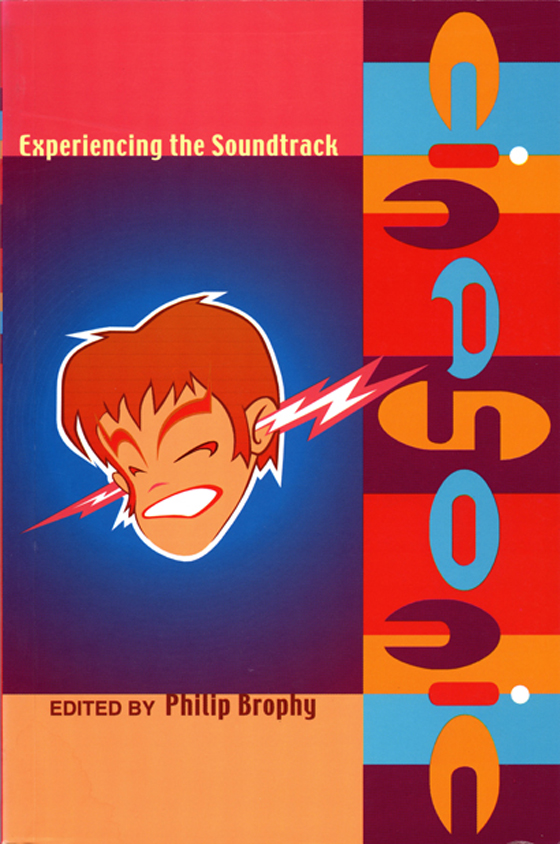

The 3rd Cinesonic conference was instigated and directed by Philip Brophy as part of his research while lecturing in Media Arts at RMIT University, Melbourne. A 246 pg book was published by the Australian Film TV & Radio School, Sydney. It contains the proceedings from the 3rd Cinesonic Conference and is edited by Philip.

Performance © 1970Credits

Director - Philip Brophy (lecturer in Audio Visual Concepts & Soundtrack)

Production manager - Monica Zetlin

Technical assistance - Jennifer Sochackyj (MA in Media Arts)

Production assistance - Camilla Hannan (MA in Media Arts)

Publicity & promotion - Scott Goodings

Original website - Haima Marriott (graduate in Media Arts)

Site support - Adrian Miles (RMIT Communication Studies)

Administrative support - Shane Hulbert (graduate & MA in Media Arts)

Support - Les Walkling (senior lecturer & course co-ordinator of Media Arts)

Major financial support - City of Melbourne, Cinemedia, the Australian Film Commission

Sponsors/support - Show Group, Australian Film TV & Radio School, Australian Film Institute, Mushroom Music, Sony ATM Publishing, BMG Publishing, Soundfirm, Digidesign, Soundworkx, Zu Music, APRA, Real Time, Atlab, Metropolis Audio, Mister Moto

Special thanks - the Cinesonic volunteers

For the book: funding through AFTRS - Rod Bishop; editorial assistance - Adrian Martin; proof-reading - Gerard Hayes

2000

Capitol Theatre & Treasury Theatre, Melbourne

2001

Cinesonic - Experiencing the Soundtrack - published by AFTRS Publishing, Sydney

The Exorcist © 1973Overview

There is no subtlety in sound design these days. Movies are too loud these days. Too many pop songs destroy movies these days. There are no great film scores these days.

'These days' is an era wherein film sound is changing, yet audiences' reactions to those changes remain unacknowledged and uncharted. The heightened aural receptiveness of the audiences of today perfectly mirrors the reduced receptiveness film theory and criticism has accorded contemporary cinema, sprouting a rash of pap altruisms (referenced above) which lamely voice a conservative desire for a visual, literary art form they call 'the cinema'. Despite the long trail of silence which wheezes forth from sleeping academia's nostrils, the audience has been well and truly listening ever since the 80s' THX cinema trailers solemnly stated as such.

This collection of articles speaks of what can be heard. From pop songs in Dazed & Confused to lush romanticism in The Mark of Zorro to Kubrick's use of Strauss in 2001: A Space Odessy; from American voices in Godzilla: King of Monsters to Australian accents in Priscilla: Queen of the Desert; from the glass harp in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest to guitar feedback in Mallboy; from the fracture of song by Dennis Potter to the diffusion of song in dub music; from the sound of speech in silent movies to the space of speech in Dolby Digital.

The publication from the 3rd Cinesonic conference is dedicated to the late Jack Nitzsche - with the hope that the many unsung film composers, score producers, sound designers and production mixers can be contacted, heard, and given due praise so as to uncover their oft-ignored contribution to this thing we sonically call 'the cinema'.

Taxi Driver © 1976Technical

Issues in Film Scores & Sound Design

Jack Nitzsche

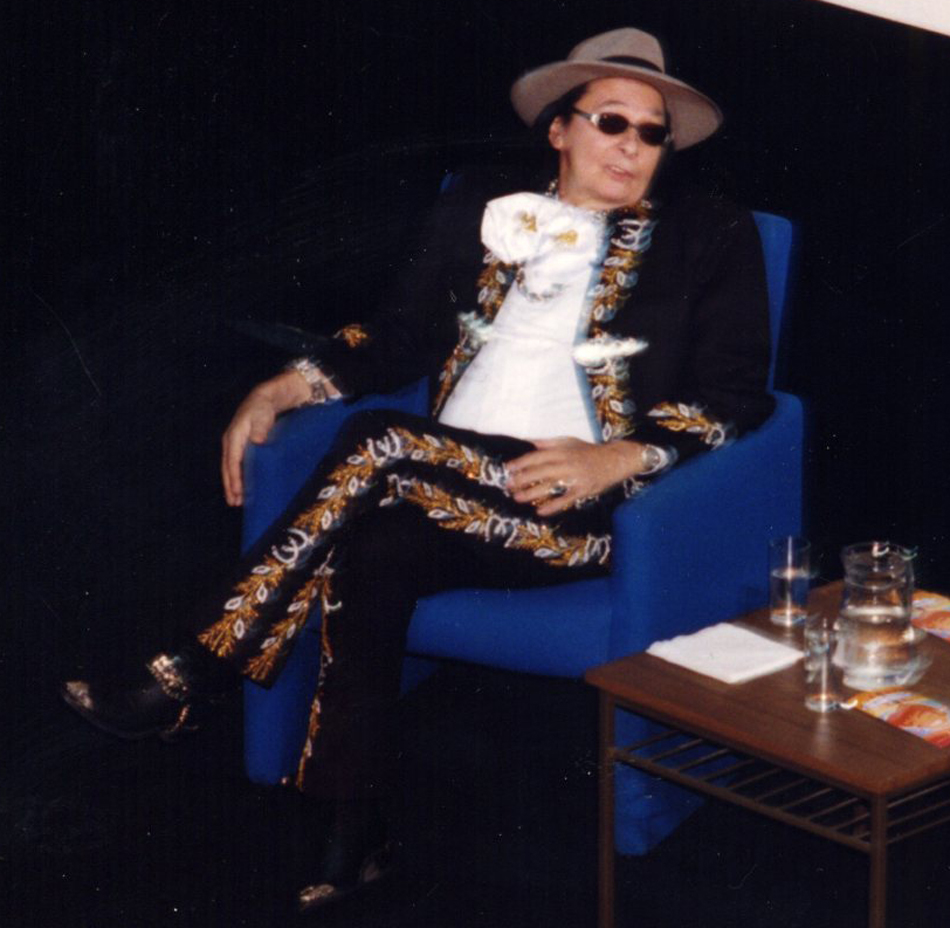

Revolutionizing Cinema - or, how I put Rock'n'Roll in movies

One wonders why film history has ignored Jack Nitzsche. The guy has moved from cool cult twang (check the opening credits to the classic Village of the Giants) to truly radical son-musical collages (Performance is way ahead of its time) to winning an Academy Award (for writing "Up Where We Belong" for An Officer and a Gentleman). Maybe he gets passed by because he has rarely delivered the orchestral niceties, which remain the tacky hallmark of quality cinema. But the reasons for his invisibility are more complex than aesthetic conventions. For Jack Nitzsche is a living breathing merger of two strains which govern the audio-visual nature of cinema: score composing and music producing. Born of the rock/pop recording industry yet a rock migrant in the cinema, Nitzsche did not simply write music, and then get an orchestra or ensemble to record it on a sound stage. He treated the score as he would the recording of an album: the musicians were crucial to the resulting sound, as was Nitzsche's role in engineering and producing the music he directed them to play. This is why a distinctive "Nitzsche' sound is hard to discern: he blends well with the musicians of his choice, and in doing so develops a character peculiar to each individual film.

The baggage that Nitzsche brings to the cinema is normally not allowed to pass thought the film industry's cultural metal detectors. You see, Nitzsche doesn't simply 'recreate' the sound of rock when it's needed for a scene: the guy arranged for Phil Spector and went on to produce for the Rolling Stones, Neil Young, The Monkees and The Cramps. In the sonic sense, he is the real thing. When he scored muzak-inspired 'beautiful music' for One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest, he did so without resorting to camp or knee-jerk counter-culturalism. When he got Captain Beefheart to contribute vocals to his blues score for Blue Collar he created a post-roots modern machine thump. And when he fused Miles Davis with Taj Mahal for The Hot Spot he produced a uniquely po-mo collage whose influence is still felt in many ambient '4th world' projects since. Frankly, many other claims to eclectic scoring pale in the face of Nitzsche's prodigious output. And while film history is still yet to sing his praise to the full, it is impossible to ignore his contribution to strategically working the soundtrack as a site for truly modern manifestations of rock's infection of the cinema.

Referenced films: Village of the Giants, Performance, One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest, Cruising, Blue Collar, Starman, Stand By Me, The Hot Spot, Indian Runner, The Crossing Guard

Jack Nitzsche in Q+A with Philip Brophy, Melbourne, 2000Bruce Emery

Beyond the Matrix - Dolby Digital Multichannel sound now

Vince Giarrusso, Fiona Eagger & Philip Brophy

Mallboy - A case study of sound & music for an Australian feature

Satanic Noise & Screaming Rock'n'Roll

The Exorcist + Sympathy for the Devil

William Friedkin's The Exorcist (1971) is a well known contribution to the modern horror film. What is less noted is the unique position it occupies in the history of film soundtracks. The sound effects design by Ron Nagle, Doc Seigel & Fred Brown is a landmark in brute sonic violence. The first half of the movie employs loud sound effects which continually and harshly rupture the domestic silence of the family home, which serves to amplify the hidden demonic forces which well from within the progressively possessed Regan. The fact that so much of the final series of demonic expulsions eschew musical accompaniment indicates the rigor and purpose of the sound design. Music, though, does creep throughout The Exorcist; a cool selection of tracks featuring some incidental themes by the inimitable Jack Nitzsche, a Japanese muzak version of Tubular Bells (!), plus chilling passages by George Crumb, Anton Weber, Bela Bartok and Kryzstyzof Penderecki.

Jean Luc Godard's Sympathy for the Devil (1970) is less an excursion into the bowels of Satanic forces and more a fascinating sono-doco of the recording of The Rolling Stone's classic song. True to Godard's excavation of the filming process, Sympathy For The Devil records every stage of the Stones' time in the studio - from their first fumbling chord work-outs to the gradual layering of tracks for the final mix. Godard employs a ground-breaking series of long circular tracks which calmly move around the large studio space while the Stones and their entourage go about their business. Juxtaposed with the Stones' studio noodling is a series of portraits of Black Panthers; decked with real guns &endash; proclaiming radical dogma whilst sitting atop derelict cars in a junkyard. Definitive Hip Hop before its time.

This double bill is introduced by Adrian Martin - long-standing admirer of Godard and renowned for locking the doors to the theatre when he used to screen The Exorcist to unsuspecting film students.

Sympathy For The Devil © 1968Sounds of the City

Taxi Driver + Playtime

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976) features the last film score composed by Bernard Herrmann; famous for his deeply brooding work for Orson Welles, George Pal, Ray Harryhausen and Alfred Hitchcock. Typical of his seething, sighing and heaving orchestral surges, Taxi Driver showcases Herrmann at an estranged intersection between lyricism and modernism. Two chord patterns elegantly breathe in and out, timed to the numerous slo-mo passages of passing traffic, matched to the rising clouds of steam which float from the New York subways. A striking audio-visual portrait of Manhattan which also includes a suitably neurotic sound design by the renowned Walter Murch.

Jacques Tati's Playtime (1967) is possibly the most stylish audio-visual treatise on modern life committed to film. Through a sharp and incisive deployment of urban planning, architectural erection, industrial invention and interior design, Tati parodies the obsessive drive by the middle classes not to succeed, but simply to relax. Vinyl couches, elevator muzak, automated food dispensers and heavenly cars populate Tati's world so as to tyrannize its inhabitants with unending noise, interruption and insomnia. Once having heard this film, the 'sound of the city' will take on new meaning. Taxi Driver and Playtime serve well as polarities in how the sound of the city is figured and inverted. Both terrify in their own way: Tati's use of muzak and sound effects is sometimes as unsettling as Herrmann's abuse of orchestrated jazz tonalities. Both work to soothe through applications of sonic salve: Herrmann's score is the slow yet cathartic release of pent-up angst born of urban pressure.

This double bill is introduced by Philip Brophy - long-standing user of public transport and advocate for the banning of Walkmans.

Playtime © 1967Transformations of Songs into Soundtracks

Adrian Martin

MUSICAL MUTATIONS: BEFORE, BEYOND AND AGAINST HOLLYWOOD

Referenced films: Same Old Song, Up Down Fragile, Pennies From Heaven (BBC TV & US film), Ally McBeal, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Une Femme Est Une Femme, Dancer In The Dark, The Hole, Pierre le fou, Les Demoiselles du Rochefort

Ian Penman

GARVEY'S GHOST > K L A N G! < HEIDEGGER'S GEIST

Jeff Smith

TAKING MUSIC SUPERVISORS SERIOUSLY

Referenced films: The Graduate, Easy Rider; Midnight Cowboy, Saturday Night Fever, Roadie, The Ice Storm, 200 Cigarettes, Can't Hardly Wait, Ten Things I Hate About You, Singles, Forrest Gump, Waiting to Exhale, The Crow, Boys on the Side, Bulworth, Dazed and Confused, Batman Forever, Twister

Considerations of Musical Identity

Krin Gabbard

REDEEMED BY LUDWIG VAN: STANLEY KUBRICK'S MUSICAL STRATEGY IN A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

Referenced films: A Clockwork Orange, Paths of Glory, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut

Anahid Kassabian

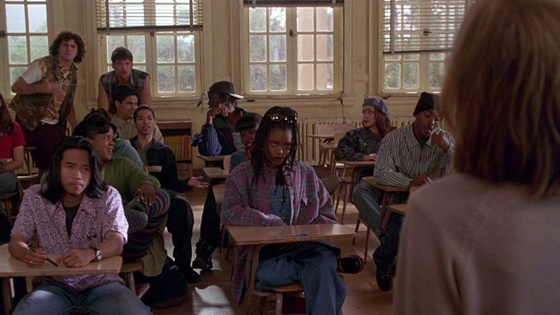

LISTENING FOR IDENTIFICATIONS: COMPILED VS. COMPOSED SCORES IN CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD FILMS

Referenced films: The Mask of Zorro [1998, d. Martin Campbell, music by James Horner]; Dangerous Minds [1995, d. John N. Smith, music by Wendy & Lisa]

Contexts for Voice and Speech

Bill Routt

HEARING SILENT FILMS

Referenced films: A House Divided, Hypocrites, Alias Jimmy Valentine, A Florida Enchantment, A Fool There Was, And The Light Went Out, The Children & The Major, Trooper Campbell, The Sick Stockrider

Rebecca Coyle

SPEAKING 'STRINE': LOCATING 'AUSTRALIA' IN FILM VOICE & SPEECH

Referenced films: Walkabout, The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, the Mad Max trilogy [Mad Max, Mad Max Road Warrior, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome], Crocodile Dundee, Muriel's Wedding, The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert, Kiss or Kill, Toyota car advertisement

Philip Brophy

FUNNY ACCENTS: The Sound of Racism

Referenced films: Farinelli, Rock, Rock, Rock!, What's Up Tiger Lilly? [1966 d. Woody Allen from the original Kokusei Himitsu Keisatsu: Kagi No Kagi, 1964, d. Senkichi Tanaguchi]; Godzilla: King of Monsters [1956, d. Terry Morse from the original Gojira, 1954, d. Ishiro Honda]; The Queen of Blood [1966, d. Curtis Harrington from the original Niebo Zowiet, 1959, d. Aleksander Kozyr]