Ennio Morricone

Ennio Morricone

Introduction

The infamous spaghetti western. Born in the 60s and derided for decades as a kitsch dissolution of the most epic of American genres. But many people missed what the so-called spaghetti westerns were about. Firstly, they were Italian. Secondly, they were operas. Violent, maybe – but so is Shakespeare. Bombastic, yes – but so is Rossini. Full of pastiche, passion and power, spaghetti westerns are typified as much by their soundtracks as they by their imagery.

Italian movie scores overall are possibly the only modernist take on what in most other cultures has remained a turgid, high-art 19th Century affair. Where America still favours the Wagnerian overdrive, Italian cinema has always had its ear to pop music on the radio. There are many reasons which separate Italy from the American tradition. Key factors include Italy’s folk and oral tradition of song; Italy’s thorough technological integration of its post-war film industry with its post-war recording industry; and Italy’s sheer delight in the excessive, heightened, ornamental and pneumonic aspects of record production.

Today on Traces of Soundtracks we’re focusing on the composer and one composer alone who embodies this entirely: Ennio Morricone – master of the spaghetti western score, maestro in any genre, and composer of over 400 film scores to date.

Once Upon A Time In The West (1968)

In Sergio Leone’s 1968 film ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST, Morricone provides one of his most sophisticated scores. In the film’s opening, three cowboy hitman wait for their target to emerge from a train that has just arrived at a barren outpost. With no victim in sight, the hitman are about to leave, but are halted by a wailing harmonica – complete with distended reverb. The hitmen’s response mirrors our double-take: is this a sound effect, part of the music score, or simply unqualified noise? Well, it’s all that and more. It’s Morricone.

There are many instances of musical grandeur and thematic orchestration in the opulent soundtrack to ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST. Yet they all whirl round the harmonica’s morbid leit motif as both aberrant aural sign and composed musical device. This harmonica theme appears whenever the hero played by Charles Bronson appears. And he mostly appears with harmonica in mouth, breathing through it to play his signature seething which symbolises the revenge he seeks.

The harmonica also expresses the memory of the hero’s brother being hung – Bronson’s character was forced to play the instrument as he watched his brother die. Bronson’s character thus becomes his harmonica, wearing it around his neck like a dead albatross; inhaling its dissonant odour each time he exacts revenge on all complicit in his brother’s death. The name of Bronson’s character? Harmonica. The notes he plays also form the recurring high-pitched train whistle, symbol of the train company, whose owner has hired numerous hitmen to kill him.

Vergona Schifosi (1969)

The Main Title Mauro Severino’s 1969 film VERGOGNA SCHIFOSI (translated as DIRTY ANGELS). It’s a world away from ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST – but that’s Morricone: a master of many style. Morricone has always expressed a fondness for the human voice. But his attraction to vocal sonority is quite distinct from the quest for the penultimate operatic aria. Morricone perceives and employs vocal colours and types in relation to each other. In effect, Morricone orchestrates dialects and diaphragms, tongues and tones. In the multi-layered vocalese of VERGONA SCHIFOSI, the effect is like a musical version of the vociferous din resonating at Rome central station, visited by an angel from above.

Ecce Homo (1968)

That same angel appears in many of Morricone’s scores. She’s actually human: the inimitable Edda Dell’orso. Her voice is the first thing heard in Morricone’s score to Bruno Gaburro’s 1969 film ECCE HOMO (translated as BEHOLD THIS MAN). Dell’orso murmurs a quasi-Grecian semi tonal incantation which is picked up and draped around her corpus by a confined ensemble of flute, viola, harp, marimba, vibes and percussion. Her siren voice floats throughout the score, sometimes in close breathy relief, other times in echoic displacement. The instruments stretch her, mimic her, replace her, voice her. This uncannily replays the film’s psychologically tense sexual drama as three men are captivated by a woman in a remote seaside village. The Mediterranean primitivism connoted in the main title to ECCO HOMO is less a display of avant-garde peformance techniques and more Morricone’s own portrait of the sexual revolution in this tersely erotic score.

Il Diavolo Nel Cervello (1972)

The sprawling ties between the psycho, thriller and espionage movies in Italy throughout the 60s and 70s form an encyclopedia of whodunit clichés. Perversely and playfully, music played a big role in building the atmosphere to these cinematic games. The two pieces from the soundtrack of Sergio Sollima’s 1971 film IL DIAVOLO NEL CERVELLO (in English, DEVIL IN THE BRAIN) provide a snapshot of this generic game play. True to the modular format of these whodunits, Morricone takes a brace of themes and then with appropriate perversity ties them into knotted configurations, each overlaid on the other. Based on the opening yet incomplete phrase of Beethoven’s FUR ELISE, Morricone’s undying inventiveness accelerates us through the harmonic permutations that can be divined from Beethoven’s simple phrase. The result is a proto-form of spectralism. And despite its formal game play, its sensuality remained unimagined by the arch romanticsm that minimalists develop a decade later.

Cop Killer (1983)

Morricone seems to have an insatiable appetite for threading the DNA of a melodic refrain through a series of unexpected transformations. Part serialist, part spectral mode, he fashions his own musical motifs in a breezy and open-ended way. This accounts for two factors that distinguish his work: 1 – the unique sonic character born by the orchestration of each score; and 2 – the engaging and innovative pathways his arrangements draw-out from their original melodic material. It’s almost as if there is no grand scheme to be stated by writing suites and movements. Rather, we are asked to enjoy the scenery wherever we are taken. In his score for Roberto Fainza’s 1983 film COP KILLER, the clichés of crime and corruption in the cold dark city are seeded from stock chromatic scales in the bass register. But an entirely unique musical tree sprouts forth.

The Serpent (1973)

Morricone composed many scores which harkened back to one of his early serious music projects: the improvization group Nuova Consonanza Muica. A clutch of dripping and shivering atonal sketches from his score to Henri Verneuil’s 1973 film THE SERPENT bears that legacy. Bowed cymbals and prepared pianos are combined with some abrasive electronics. Their improvisatory gestures create a thoroughly engaging soundscape, sophisticated in both arrangement and stereo spatialisation.

But perhaps one of Morricone’s most radical scores is for the 1970 film by Dario Argento, THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMMAGE. Emblematic of the Italian Giallo genre of murder mysteries and their often violent transposition to the screen, Morricone conducts and controls the free form improvisations of this score like a psychiatrist in a strange laboratory. Rattling, rustling and humming enliven the air like electricity. This is Morricone responding to the post-Stockhausen world of acoustics mixed with electronics.

The Bird With The Crystal Plummage (1970)

More than possibly any other film composer, Morricone is one to whom the recording studio is something to be actively engaged. Only he can write 16th Century madrigals for wind ensembles, and record them with echo. Moreso, Morricone never hides the studio processing from the act of recording. His recordings and productions are openly plastic – like all good opera. If only more film composers embraced this phonological reality of the film soundtrack.

Moses The Lawgiver (1974-5)

From the mania unleashed by voices screaming in pain to the ominous voice of God himself. The score to the 1974 TV mini-series MOSES THE LAWGIVER required a musical interpretation of God’s Voice. Morricone undertook the task with typical flair. 15 years before Martin Scorsese’s controversial retelling of Christ, Morricone coloured his score with the Middle Eastern tones that perfectly joined tonality to the movie’s landscape. More interestingly, Morricone used atonality and expanded performance technique to supply an omnipotent sense beyond human scale and form. Only the culturally-deaf would presume that the voice of God would be humming Strauss.

Morricone’s sensitivity to the emotional shivers that music can produce beyond the human threshold mark him as a modern composer uprooted from the pastoral idyllicism of the 19th Century. Sure, he could conjure forth glistening chalices of harmony from the bottomless well of beautiful music, but Morricone’s modern ear could only concede that beauty as such belongs to a bygone era. Remember, Morricone comes from the same nation that bore the Futurists.

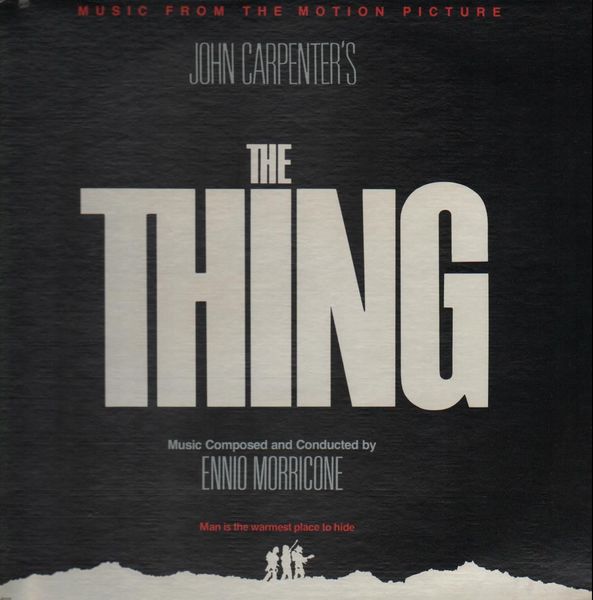

The Thing (1981)

So when Morricone wishes to sharpen the glint and hone the edge of his musical rendering, he does so with unnerving verve. His score to John Carpenter’s 1981 film THE THING is precisely that: a ‘thing’ of music. Based upon a monstrous mutating form that genetically mimics human form, Morricone’s score to THE THING is like a genetic mutation of harmonic scripture as written by musically gifted humans. But in place of the destructive programme of many modernist composers, Morricone composes like a cool scientific observer. He impassively allows the notes to wither, contract, merge and gorge each other. In his own way, he echoes what many modernist composers implied: that nature is impossibly beyond human scope, and that if it does withhold beauty, it does so at an unhuman scale.

Morricone’s music often comes close to an act of decomposition. THE THING cries out for this approach, and serves as a symbol for how music can be stretched to accommodate anything. THE THING’s score returns us again to the ungainly meld of the monstrous with the atonal, but listening to it is not that terrifying. Centuries of theological and religious dogma collared western musical harmony. But despite the narrowed field of sonic possibilities available, sublime music was created. 20th Century atonality in both its strident and relaxed guise pulls back to reveal a much vaster sonic landscape. But far from the simplistic rhetoric of ‘the shock of the new’, Morricone’s film music of this bent is typically Italian. It’s a polyglottic savouring of a boldly wide tonal range. His most famous recent score – THE MISSION – drips with beauty. But THE THING beautifully drips.

Outro

Ennio Morricone. Kitsch and sublime. Earthy and transcendental. Just as opera reinvents the dynamics of the world upon a wonderfully plastic stage, so does Morricone’s music create gilded environments wherein all manner of drama can unfold. And being Italy, it's a celebratory democratic stage, where peasant and king can share a meal. Where spine-tingling string arrangements can blend effortlessly with a wailing fuzz guitar.