Reverberant Oscillators in Outer Space

Reverberant Oscillators in Outer Space

Cinematic Electronica Part 1:

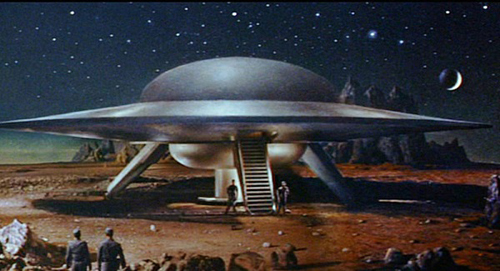

published in The Wire No.158, April, 1997, LondonHollywood. Science Fiction. 1956. Canary yellow and bright red 3-D lettering zooms forward: FORBIDDEN PLANET. The background is space - Griffith Observatory style diorama space; deep blue dotted with milky swirls of stars. This is America's 3-D era, when everything shot forth, penetrated deep, became form. From giant donuts and flying saucers on your roof to Cinerama can-can girls' crutches in your face. But if objects and images must be big, bright and bold, how will they sound? They will sound reverberant. As FORBIDDEN PLANET's credits roll across the screen against a vast vacuum of night, all sound reverberates in echoic bleeps and tubular squawks. Such specious logic: sound of course does not operate in airless outer space as it does within earth's atmosphere. In space no one can hear your reverb. But this is Hollywood. Science Fiction. 1956.

Louis & Bebbe Barron's solely-electronic score for Fred McLeod Wilcox's FORBIDDEN PLANET (56) is a landmark soundtrack for many reasons. Apart from uncomfortably networking a transplanted European avant garde with the emigre European executives running Hollywood at the time, the film signposts the clumsy audio-visual fusion of 'electronics' with 'sci-fi' which persists today. Outer space still sounds out rightly weird and outwardly electronic. FORBIDDEN PLANET's electronics may sound corny, but its rarity as a film score secures it historical savvy. It is safe - and sad - to say that 99% of Anglo, American and European film scores inherited and proclaim a 19th Century aesthetic. Cinema has pompously espoused its 'truly 20th Century art form' schtick since its inception, yet an ever-widening gramophone speaker remains impaled through, say, Franz List, Richard Wagner, Alex Korngold and John Williams. The sound of the 19th Century now bellows from their bowels in Dolby Digital Stereo. This is symptomatic of the crisis that persists when the sciences and the arts collude and collide: technology surges forward, using aestheticism to 'naturalize' the shocking newness technologies foster. FORBIDDEN PLANET's musicality naively yet fortuitously underscores this cultural conundrum by proposing that the new frontier of space should usher in a new aesthetic dimension. The pre-war avant garde recognized this only too well. Cinema is yet to holisitcally perceive this - especially in regards to music and sound.

Back to reverb. Reverberation has been possibly the most sensorial and tactile aspect of acoustic phenomenae for most cultures since the big bang. Reverb is the penultimate sensation of -literally - sound occurring outside of itself, of sound leaving a sonic trace of its absence. Psycho-acoustically, reverb consequently gives us an out-of-body experience: we can aurally separate what we hear from the space in which it occurs. When the 20th Century really kicks in - typically, when WWII assembles and unleashes a myriad of accelerating destructive technologies - reverb is rediscovered as an 'electro-acoustic' feature of recorded sound. When Pierre Henri & Pierre Schaeffer started reversing magnetic tape in 1947 they heard reverberation precede the event which created it. Simultaneously trippy, corny and profound, this sensation has to wit propelled the design lineage of reverb units - from chamber resonance to spring tension to tape loop to real-time sample. In other words, reverb was made consciously apparent only after it was reversed and denaturalized.

Back to the film. Reverb is grossly employed in FORBIDDEN PLANET (and all ensuing 'spacey' film scores and sound designs) firstly to invoke the expansive opening of interplanetary frontiers, and secondly to evoke an imposing sense of size and space. At least fifteen centuries of European church architecture used reverb to conjure up (in separate epochs) social amorphousness, individual erasure, thundering scale and omnipotent power. Sci-fi movies have followed suit with their own brand of technological mysticism and god-fearing morality. FORBIDDEN PLANET is thus a wonderful sign of its time: archly spooky, frighteningly empty and electronically baroque.

Yet there is more. The film's production design proposes that the planet's deserts are remnants of oceanic regions, hence the film looks like an empty fish tank cluttered with hardened coralular and spongeforic formations. And just as the music score emphasises reverb where there cannot be any, so too do 'bubbly' sounds percolate incessantly, incongruously overlaying an underwater presence on a barren visual terrain. Of course, sounds heard by our ears underwater do not carry the full-frequency detail with which film music and sound portray aquatic conditions and sensations. In a bizarre match of wacky logic, the out-of-body experiences of reverb-in-space and aquasonics-on-land perfectly complement each other in FORBIDDEN PLANET. The acoustics are unreal, the sound is watertight, and the symbolism is sound. The postwar space race introduced an array of similar illogical, crazed and charming sono-musical icons: the arrhythmic, echoic twang of rockabilly songs yodelling about atomic power; the pseudo-sophisticate savouring of hi-fidelity jet engine sound effects in the loungeroom; the joy of twiddling the dial on portable short wave radios; the cosmic and orgasmic symphonies of theremins, oscillators and vibraphones on record and in the cinema. Certainly a prevailing trash aesthetic reduces much of this iconography's complexity to the otherwise enticing celebration of 'exotica', 'easy listening' and so on, but this does not preclude music born of the space age from embodying cultural and artistic depth.

Listen to Bernard Herrmann's use of theremin with orchestra for Robert Wise's THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL (1951). On the one hand guilty of again branding electronics with outer-space-weirdness, Herrman incorporates the instrument with traditional orchestration so as to blend textures of familiarity and strangeness in an unfamiliar setting. His theremin motifs symbolize extraterrestrial energy that powers Klaatu's spaceship and his robot Gort. Through the music, we hear the sound of that energy - an indication of Herrman's astute understanding of the potentiality of electronics when combined with musical instruments. A key figure in 20th century film scoring, Herrman always knew the psychological purpose behind any 'mood' he generated through his compositions and instrumentation. Herrman returned to electronics over two decades later for one of his final scores, Larry Cohen's IT'S ALIVE (1974). The score boasts some freaky analogue synth stings which wreck havoc with the orchestra's warbling and surges. Clearly the ugly synthesizers symbolize the hideous mutant baby, as out of place in hyper-normal LA as a voltage-controlled filter in LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE.

Electronica in the fifties meant outer-space. In the sixties it meant inner-space - the erogenous body. The most artistically cheesy but gorgeously hedonistic example of this is Roger Vadim's BARBARELLA (68). Milanese design meets Parisian electronica meets London fashion meets Hollywood stars. Every design crevice of the film is moist with camp, imbuing it with a timeless hipness. Effectively, the score by The Bob Crewe Generation Orchestra (mixed with much uncredited electronic atmospherics) is Burt Bacharach and Michel Legrand ooh-aahing in outer space, combining erotica with electronica, Francophilia with intoxica. The new era aural cheese of The Bob Crewe Generation Orchestra bluntly but beautifully combines FORBIDDEN PLANET's aquatic tummy rumbles with suburban California swinger jazz muzak, all set to the widescreen landscape of Jane Fonda's navel. BARBARELLA - born from a comic strip and made flesh by the genes of the Fonda family - evidences the critical grey areas that arise when the avant garde and pop culture are cauterized in the creation of a film soundtrack. Artistic purity may be nullified, but transcultural germs spread like a glorious musical plague.

The influence of this meld can be heard in countless late sixties and early seventies easy listening albums where the latent/repressed sexuality of white jazz is massaged and cajoled by viscous, anti-gravitational synth tones. The effect is one of a cerebral and physical weightlessness - urging one to go with the flow, intake now-generation aphrodisiacs and swing with the suburban set. 'Revolutionary' sexuality seemed to require an audio-visual copulation between electronics and erotics. Spacey sexy synths and pseudo-theremin glides appear in Curtis Harrington's QUEEN OF BLOOD (66, score by Leonard Morand); Roger Corman's THE TRIP (67, music by An American Band); Otto Premiger's SKIDOO (68, score by Harry Nilsson); William Rostler's MANTIS IN LACE (68, score uncredited); ALICE IN ACID LAND (c.69, uncredited muzak tracks); Russ Meyer's BEYOND THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS (70, score by Stu Phillips); Nicholas Roeg's PERFORMANCE (71, music supervised by Jack Nietzsche); Michael Crichton's WESTWORLD (73, score by Fred Karlin).

Across thirty years, synthesizers in film soundtracks had shifted from a fifties' space age utopia through a sixties sexual cornucopia to a seventies erotic suburbia. Perhaps this is why only now can the retro-concept of 'space age bachelor pad muzak' be so obviously pleasurable. Yet while synthesizers have attained the so-square-they're-cool status in pop/rock/dance music, the technical and formal balance between digital construction and analogue electronica since the 70s has affected and influenced film scores and sound design profoundly. And it is within this terrain that synthesizers are no longer weird: they become perversely futuristic, timbrally pornographic and radically dimensional.

Text © Philip Brophy 1997. Images © respective copyright holders