Digital (f)Art

Digital (f)Art

Four Manias

catalogue essay for Trick Or Treat, 200 Gertrude St., Melbourne, 1997Mania 1: ontological neurosis

The great thing about digital art is its virtuality - the joy that nothing is there, and that you don't have to have a 'feel' for anything because there's nothing to touch.

Architects used to control this domain. On gorgeous linen plans they could project a vision of the world they would never have to inhabit. Sitting on tall stools with upright backs in front of a drafting board, they would obsess over perspective, like they were covering the world from every angle. And those cute Letraset libraries of trees, cars, people, pets. Life at the scratch of a nail.

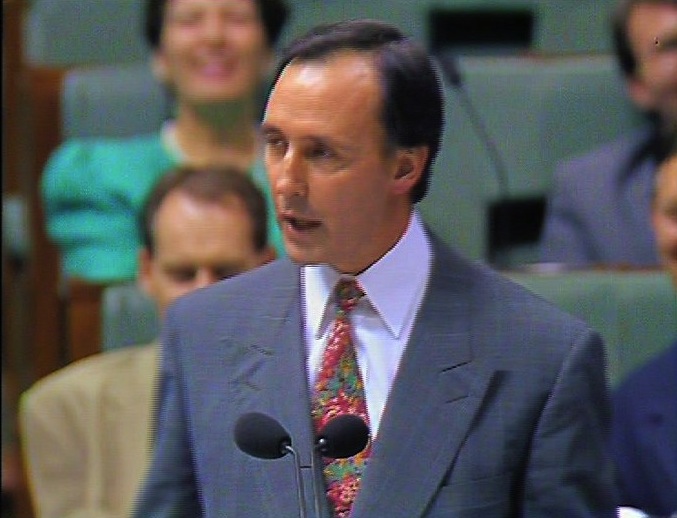

The digital fraternity now embrace architects as a subset - the CAD guild - who sweep across the X-Y axis on their walk-throughs like a drag queen wagging her finger on cat walk. Illustrators, photographers and other quaintly-named professions are co-joined by the precision of their craft (at least, until they have to output). The fact that they look like DaVincian etchings of bereted ogres squinting through a grid box to draw the landscape doesn't seem to bother them. In their virtual world, the past doesn't exist, so how could they be held guilty of paradoxically returning our vision to Euclidean perspective while quoting Steven Hawkins? Who would be so crude as to claim that digital artists have set new standards of visual imperception? All art is neurotic. Postmodernism in the fine arts is the shock of the neurotic. Digital art - from wacked-out ex-video artists who once claimed monitors in galleries would destroy the cinema to fucked-up desperates who planned career moves based on Paul Keating's half-baked views on multi-media - is hyper neurotic. You can be more successful with digital art (at the moment) because everyone will presume that there is an actuality to your virtuality. And you - being a digital artist - will probably agree with them.

Mania 2: temporal dyslexia

Computers are real fast. Like, really, really fast. I've seen ads on TV where an animated line zaps around the globe in a few seconds. I'm impressed. Digital art is just as fast - well, sort of. You can scan an image, pick a filter (twirls if you're trippy, blurs if you're sensitive) and blammo: digital imaging. What you'll do with that image is not so important, because you made it real fast, which is the point. You have better things to do with your time. You're a very important person. I've seen ads that tell me so.

Digital artists are advanced because they live in temporal warps, operating within a gorgeous Virillian frame of speed. This is very important for digital artists, most of whom are sex-starved. By somehow being speedy, that's the closest they'll come to sex for a long time. Perhaps because of this, a temporal dyslexia afflicts digital artists: while they spend days on end working out dumb software, they still believe that at the end when they drag a few icons and pull down a few menus that they're actually being fast and getting things done at hyper speed. Which is like believing a feature film gets made in 90 minutes. But in the digital era, time and space is all fucked up, man. Everyone from William Gibson to Doctor Spock agree. They should know.

Strangely, labor also gets fucked up. Digital artists - when working for clients - have to charge as if they're working with implements from The Flinstones to make their Kai Power Tools effects. My computer can animate things at the speed of light - but when I charge you for it I have to get out my zoetrope to calculate the motion effects.

Mania 3: numerical delusion

Digital art is really exciting. Just ask programmers and coders. They've made maths cool again. My secondary school teachers were right all the time: I should have listened to their wisdom. I too could have had ultimate power - to view life as a supreme binary switch. Zero. One. On. Off. Sort of like a numerical version of black/white, good/bad, god/devil, etc.

Programmers and coders are incessantly championed by digital artists - a pack of pseudo-scientific aesthetes - as the really creative people. The point being that once you dive into the endless swamp of metaphysical computations and possibilities, you're somehow getting to the heart of the matter. That is if you are desperate enough to believe that art should be about truth, nature, beauty, life & existence. Staking such claims for mathematicians is ultimately born of artists who have hang-ups about being artsy-fartsy, wanky & elitist. Rather than accept their flowery, powdery status, they seek validation from the most empirical of all languages: maths. Fair enough to metaphorically articulate proximity between the sciences and the arts, but please: don't introduce me to a mathematician. Or a computer programmer. I know of great plumbers without whose genius craft my toilet wouldn't run so smoothly, but I ain't going to dump them on you as a way of articulating a world view.

Fucking (or at least rimming) the arse of science is the cheapest of all self-validating practices. Like, numbers don't lie. Like, we understand the world through ratio, scale & frequency. Like, all sci-fi movies use algebra as the means to communicate to extra-terrestrial life-forces. Pure numerical delusion. These are all fantasies which lie moulding in the minds of math teachers. Now they're being extolled as visions by digital artists. A more immediate, probable scenario lies in the all-time greatest fucking-with-children's-minds movie: MAC & ME. Sponsored by Macdonald's (sic), cute aliens understand life on earth by eating a Big Mac. And we all know what computer programmers and coders eat.

Mania 4: obsessive interactivity

Everyone believes they have supreme powers in this wacky chauvinist world of ours. Sportsmen ritualize it. Serial killers enact it. Artists mysticize it. Digital artists are the worst: they believe in their power so much that they make a big deal about rejecting it. Welcome to the world of interactivity. Actually, I didn't mean to welcome you, because I want you to empower yourself to choose to enter this world. So let's try that again. (...) Hi! Welcome to the world of interactivity.

See how different that was? You chose to do it. Aren't you special? But really, I'm even more special because I'm controlling this dumb game of interactivity. I'm lying. You're not special at all. You're stupid. I'm in control, babe. Here's two icons. Which will you chose? (Duh.) Isn't life grand when you are empowered to have choice? Interactive art is sublimely ignorant of the facile illusion of choice it conjures up. As if I care which icon I click, which path I take, which role I play, which link I follow, which decision I make. Life is messy, distorted, dirty, hazy, confused, uncontrollable. Interactivity in digital art is the most escapist method imaginable to avoid this.

Stemming from the miasma of pseudo-decision-making that is interactivity, digital artists push the envelope (whatever that means) by expanding the physicality of the computer to engage the 'active user' (TV is for potatoes, man). Welcome to the fetishistic dungeon of triggering. Laser beams, light sensors, thermal charges, audio recorders, microwave transmitters, earth conductors, chemical reactions - anything that can be made to make something turn on or off will be used. I guess 'switches' are so inhuman and uninteractive. Thank you, digital artists, for making the world so more expansive for me when I stand before your myopic installation. Internet activity making your muscles twitch, barometers making triangles of colour flick around a screen, my presence changing the patch on your DX7 - never before have artists believed themselves to be so powerful. The cosmos is yours; by interacting, I share it with you. Your art is as expansive as the sticky old slides of space projected in the planetarium.

Dedicated to Marlon Brando, Sandra Bernhard, Dan Clowes & Steve Albini.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.