De-touchable Technologies

De-touchable Technologies

Between Dreams & Nightmares

published in Oberon No.3, Amsterdam, 2017Excerpt

(...)

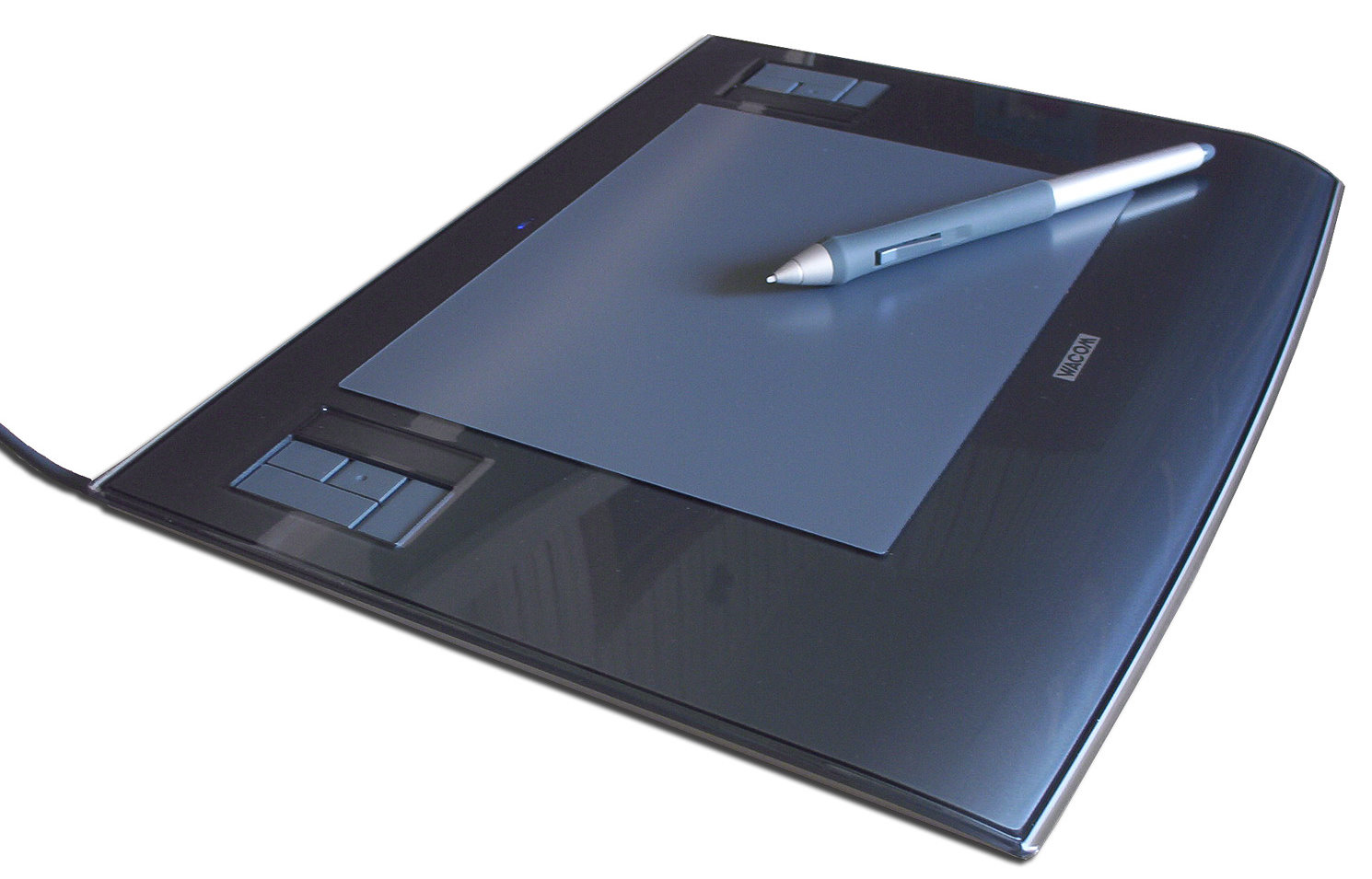

The lineage of dreaded touch follows a rich vein in the horror film’s morphology. The genre’s then-latest development interfered with standard semiotic operations and added to the noisescape of communication which, unsurprisingly, art and culture has spent the proceeding few decades attempting to clarify and interpolate as a clean communicative signal. Nowhere is this cleanliness more symbolically evident than in the mania for ‘de-touchable’ technologies. These range from the 1990s dreams of sensor-activated switch engagement to the 2010s fantasias of screen-swiping option selection. I’ll discuss these separately.

Sensor-activated switch engagement means a person’s body triggering a proximity switch to turn something on or off. This logic initially served security detection systems, wherein a criminal body would transgress space—physically—and thereby activate an alarm, either audible to the criminal or sounded elsewhere beyond his comprehension. The transgressing body here (not a radical node, merely a random law-breaker) enabled the security system to reap benefits. In other words, the criminal did the work for law enforcement by using his own body to activate and engage the security system. It was only a short step to realise how such a relationship could serve the growing field of user interface design. A ‘transgressing body’ could thus walk into a room and lights would turn on, ovens would change temperature, washing machines would commence cycles, and so on. In the process, it would be reborn as an ‘interfacing body’. The term more readily employed was ‘interaction’: the user was deluded into the idea that they were interacting, when in fact they only ever triggered like a dumb criminal.

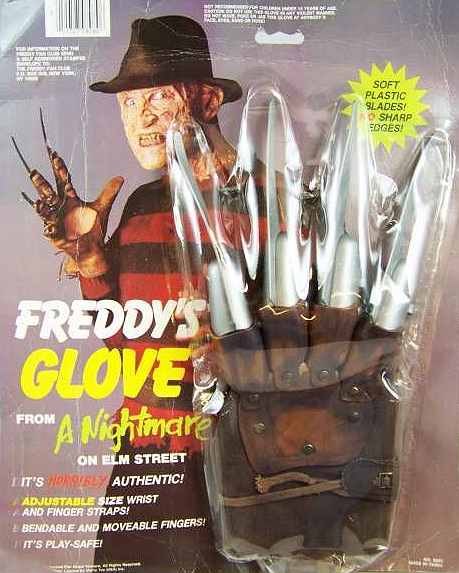

A deluge of risible specious interactive artworks and installations rode the dream wave of this design logic. The end of the millennium was crowded with contemporary art venues hosting spatially constructed events which didactically strove to convince that as you moved left or right or forward or back, you—yes, you and only you—created a unique experience for yourself. In reality, you performed like a giant flabby mouse clicking and pulling down a menu with a meagre handful of options. Worse, the artworks and installations generally obfuscated their simplistic triggering of narrow controlling options by delivering the false fantasy of interactive empowerment. Yet many gallery patrons (and a host of impressionable curators) enjoyed the mystifying wonder of this type of experience, predicated as it was on ignorance of the works’ mechanics. The result was an art versioning of a dreamspace devoid of any dread-inducing figures like Freddy Kruger. These type of gallery environments are contemporised, extended versions of the safe utopian world envisaged by the parents who killed Freddy to halt his incursion. Of course, by the new millennium, a range of technological improvements streamlined triggering. Notable advances were made in software zoning capabilities, immediate calculable response time, interconnectivity with hardware modules and all-round flexibility in matrixing possible responses to evaluated spatial movements. Yet these inventive solutions still do little to disguise the base problem: ‘you’ are doing nothing; ‘it’ is doing you.

(...)

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.