Music For & Of The Body

Music For & Of The Body

Michael Jackson's GHOSTS

published in Real Time No.20, Sydney, 1997In the Straub/Huillet film MOSES AND AARON (1976) based on Schoenberg's opera, a chorus of dancers perform a somewhat gangly mock-ritual, culminating in their surging forward to the camera, falling into an unseen heap beneath the bottom of the frame. The music score continues, with the camera holding on an empty frame of the Roman arena within which much of the film's action occurs. Ruthlessly and rigourously affixed to the dialectic of their transposition of the Schoenberg text into film, Straub/Huillet's camera-blocking simply falls dead to allow the prime text - the music - precedence and presence. Many similar 'dead' moments recur through the two and half hour film - that is, until one realizes that the scene is far from 'dead'.

The sound is live. While staring at the empty arena, we hear a mass of invisible bodies panting and gasping from the energy their bodies spent dancing. The moment is moist, saline, pornographic. It is also a reminder of how, when and where the sounds of the body are allowed to be rendered - in this case, exemplified by their privileging of live, continuous location sound recording.

Straub/Huillet are representative of an approach to film sound which has typified the bulk of European sound design for the last 30 years. The resulting aesthetic (in some cases, a politic of form) shapes film soundtracks to indelibly fuse the actual live sound of the on/off-screen action with the energy of the recorded performance in its original spatial location. Without resorting to vague, pseudo-mystical discourse, it must be stated that the simulation of densely textured live sound is extremely difficult to achieve in the post-production environment. Debates still rage across the world today as to the acceptable degree of naturalism and artificiality in film sound. The French, in particular, seem very divided about this still. Yet while they have tended mostly to reject the Hollywood model of excessive post-production - which, ironically, owes much to French musique concrete - they nonetheless have given us rich models of how live sound can be employed as a vast reservoir for the dimensional irrigation of cinematic soundscapes (for example, in the work of Jean Pierre-Melville, Jean Luc Godard, Margueritte Duras and Alain Robbe-Grillet).

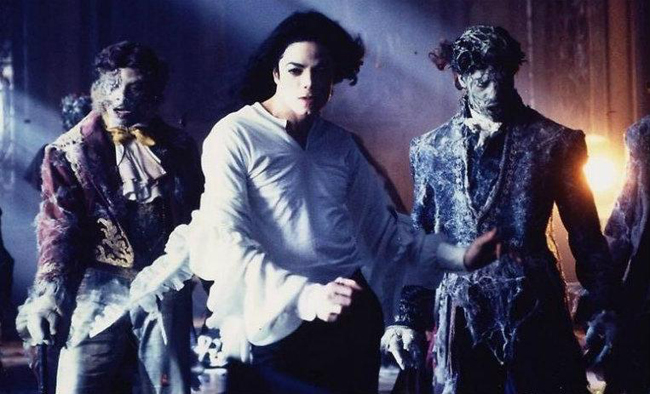

That sonic moment of exasperation in MOSES AND AARON rarely surfaces in the cinema. It happens in pornography, naturally enough, where any and all bodily audio-visuality can eroticize the clumsy proceedings. It happens in loquacious, brutish films by Sidney Lumet, Robert Aldrich, Arthur Penn, Robert Altman, John Cassavettes and Abel Ferrara, where the throat, chest and voice of actors are struck like drums to perform with a heightened sono-physical presence. And it happens most of all in the video clips of Michael Jackson. In THRILLER (1983), the protracted dance sequence overflows with the sound of bodies: gasping, spitting, heaving as their animated corpses (and yes, that's all the screen body is no matter how you dress it up) are energized by the music. The sound of the body is always celebrated by Jackson - not only in his self-multiplication and self-granulation into a myriad of snap-crackle-and-vocal-pops for his songs, but also in the overlaid sound effects for nearly all his video clips: the foot stomping of THRILLER, the sexual humping of THE WAY YOU MAKE ME FEEL (1986), the kung-fu chopping of BAD (1987), the primal screaming of BLACK OR WHITE (1992).

GHOSTS (1997) recently aired on national television with the pomp and circumstance which accompany all Michael Jackson 'premieres'. As the hype and special effects hoo-hah resides, I am reminded of how little truly contemporary apparitions of radical sound design exist in that oozing pool of audio-visual potential we call the cinema. GHOSTS stands as a unashamedly freakish pillar of bodily difference and sonic distinction. Like the uncompromising work of Straub/Huillet, it ruptures the dull felt blanket which muffles film sound, giving rise to aural experiences and tactile imaginings.

But before discussing the sound design of GHOSTS, let's be clear about a few things to do with 'the cinema'. In its admittedly strained attempt to 'be cinema', Michael Jackson's video clips transcend cinema. They do not fall short in the pomo pit of pathetic allusions of quotation and appropriation; nor do they deconstruct/reconstruct historical film texts. In an epoch of cinema held to ransom by 19th century music and 18th century novels, Michael Jackson's pseudo-cinema is more real than real. It pushes past experimentalism, beyond acinema, and into a realm of reinvented cinema. Forget the skin of the eye, its fetishized optics and attendant photochemical grain. Listen to the colour of skin and the grain of the body.

GHOSTS opens with a surfeit of cinematic cliches typical of the rock video vision, recreating the warm yet chilling world of a spooky old movie on late night television. But instead of a crackly old TV turning violins into buzzsaws, the orchestral recording is scintillating, panoramic, majestic. Listening to it in full stereo playback, one notices that this kind of mix is rarely - if at all - allowed in film music mixes. The spatialization is hyper-detailed: every instrument holds its own focal point, creating a sense of ornate spatialization that film convention would deem too distracting for a lumbering narrative. The instruments dance across the stereo field so much so that one experiences space more than sound. Such an aesthetic is born from the recording and producing of music, wherein music becomes sound in the act of recording. In film sound, music - formally, aesthetically, technically - is mostly regarded as an unmediated source, as if what you hear is 'pure music'. This has historically dictated that a blurred naturalism govern its presence and placement, as if we are at the turn of the century sitting in front of an orchestral pit of semi-muted live musicians in a dampened theatre. GHOSTS creates a sharply defined spectral environment of sound within which musicality is a by-product of its incorporation in the soundtrack. Here - as beautifully claimed by Japan's Pizzicato Five - music is organized by sound.

This in itself would mark GHOSTS at the vanguard of film sound - but there is more (most of which is beyond the scope of this brief article). This 'spectral environment' is part of a spatial narrative which unfolds as the video clip dovetails sequences, numbers, set-pieces and effects into each other. We start outside the ghostly mansion, with orchestral gestures sonically flitting about us like animated cobwebs and flickering shadows. A series of thunder cracks (the rupturing of the ether sphere) and door slams (the transgression of architecture) erupt from the soundtrack in complex figuration. Each event is a monolithic event, ground-shaking, space-warping, shape-changing phoneme, signalling an erotic transgression of forbidden realms. Upon entering the mansion, the orchestral detailing is swept up by a swirling network of shifting breaths. The space is not simply 'live': it is alive, for we are now inside the body of Michael Jackson. It is weird, it is strange, and I like it.

GHOSTS is a clear message about transgression. Michael Jackson transgresses what we call 'race' and 'gender'; now we are inside his world ("Whose the freak, now?"), and our homey, hokey, uptight sensibilities transgress the ethereal, metamorphic nature of his home turf. Michael Jackson's sense of his own being - something which most of us will only ever ridicule rather than understand its fundamental otherness - has consistently determined the sounds and images of himself which he mysteriously conjures forth and methodically sculpts. The ornate spatialization of the orchestra thus aptly reflects what could conceivably be the interior of his body. Inside, we are in a newly-defined world of sound and vision. Things behave aurally in ways unacceptable in our constricted world of sanctioned physical form. Building upon his previous tactic of overlaying sound effects, every move Michael Jackson makes - a point of the finger, a twist of the neck, a dart of the eye - is marked by a momentous sonic event. He conducts all that inhabit his terrain; he performs by aurally animating that terrain purely through his movement therein; and he generally unnaturalizes the audio-visual make-up of his depicted world. As the dancers (themselves signs of the rich and fetid roots that stem back to New Orleans Jazz and the explosion of Afro-American culture throughout the new land of America) move from earth-bound steps to mid-air flights to Escher-like gravity-defying movements, as their footsteps reverberate with a glorious artificiality that confirms their post-bodily state.

Because Michael Jackson is first and foremost a musician, his world - like MOSES AND AARON's cinematic text - obeys musical logic and aural form. (It is important to note that all other forms of narratology are either irrelevant, inconsequential or incidental, and no matter how many novels you read, a literary perspective will render you illiterate in front of this soundscape.) Listening to HISTORY (1995), one can hear the excessive ornamentation that has consistently governed Jackson's music, no matter whether he is working with Quincy Jones, Baby Ford or Teddy Riley. The funk of Jackson's arrangements is Gothic, Frankensteinian, lurid, technological. It follows the 'baroque bayou' stylings historically defined by arrangers like Barry White and Isaac Hayes and contemporaneously embraced by producers like Prince. In place of the muscular, pumped thickness of hip hop (low ground swells, deep booms, fattened slaps and grinding rhythms), Jackson has aligned himself with the slicker, streamlined post-funk of New Jack Swing. Its brittle, crystalline nature allows for hyper-detailing along a convey-belt which creates an interlocking grid of digitally-edited rhythms whose complexity is far in advance of rarefied computer music and a precursor to the often obvious editing of Drum & Bass.

The succession of songs in GHOSTS skates across shiny, eclectic, post-funked platforms. Each is heterogeneously stitched together in a fractal patchwork light years away from classical, romantic and modern form - because in funk, everything is held in place by falling apart. It is the aesthetic of the collapse and the pleasure of the breakage (as opposed to the tyrany of being 'tight' so championed by white culture), both of which can be heard in Michael Jackson's music, seen in his persona, and experienced in the sound design of his video clips. He fractures space as gleefully as he recomposes his own face; he excerpts sound as violently as he destroys his own body. In the being of Michael Jackson, a more absolute meld of sound and vision does not exist. He has left our world where plastic surgery is frowned upon, race must be black or white, music is required to be pure, and video clips are excluded from the cinema. How fitting that he now tags himself as a ghost.

Text © Philip Brophy 1997. Images © Michael Jackson/Epic