Booms, Drones & Other Dark Waves

Booms, Drones & Other Dark Waves

Lost Highway

published in Real Time No.18, Sydney, 1997There is a story - one of many - about how they built Disneyland. Apparently, if you can make your way through any of the secret entrances to the operations divisions concealed underground, you then must navigate some long, reverberant corridors. Word is that the corridors were designed to be highly reverberant because children would be more frightened by the booming sound of their own voice than the dark alone. I can't remember where I heard this story, but if it is true, it's another indication of how Disneyland is a designed environment of sublime invention and perceptual precision.

David Lynch embodies the Disneyland effect of combining and manipulating a carnival obviousness with perceptual hucksterism. In a demure archetype of postmodern pulp, he folds the fake into the real in the name of pleasure and terror. Postmodernism unfortunately has been commandeered by artists who do no more than slum it for the intelligentsia. Yet most po-mo artsy figures like Lynch are desperately modernist and pathologically Eurocentric. However, Lynch knows sound. And since he has been doing his own sound design (after sound designer Allan Splet's death in the early 90s) he has realized a series of cinesonic moments which open up the complexity of his cinema far more effectively than his visual symbolism alone has allowed.

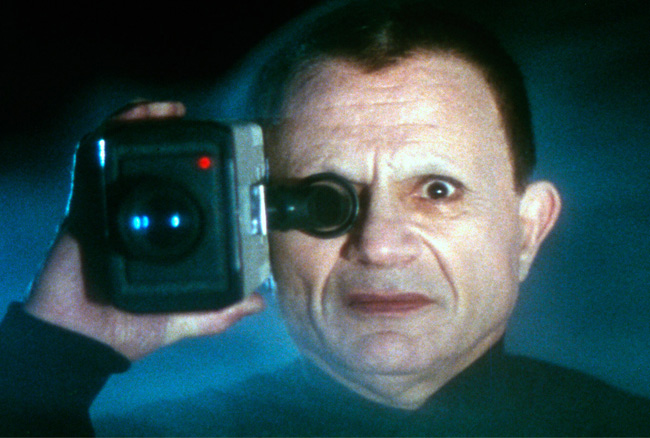

Lost Highway (1997) has such a moment - possibly the best Lynch has ever directed - when Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) walks into darkness. He stands in front of a perceptually undefined space: it could be a corridor trailing into centre-screen, or it could be a flat wall lit only at the extreme edges of the frame. Foreground, background, depth, curvature are rendered indistinct by the screen's disorienting flatness. As Madison walks forward (away from us, with his back to us) he walks into darkness itself. (We will return to this scene later.)

This intensely quiet moment happens, from memory, about 20 minutes into the film. The 20 minutes before this moment are probably even more important. 20 minutes worth of sound that creates the sono-narratological world - a designed environment like the mythical underground corridors of Disneyland - across which Lost Highway loops.

When we first enter Madison's apartment, a strange aura occupies the cinema: it is the sound of nothing, the texture of silence. That humming tone that says nothing is occurring; that ringing rumble of space itself. Location sound recordists refer to it as 'room tone'. Like room temperature, it is a palpable nothingness. It's the texture that has to be recorded separately as filler for dialogue editors, so they may seamlessly segue between passages of recorded speech. Without this sound of nothingness, location dialogue would be revealed in truth as bits wrought from a real space - a live acoustic space too great and expansive for the audio track's constructed fictitiousness to contain. Listening to 'badly edited' dialogue demonstrates this effect: you hear the dialogue hissing with room atmosphere cutting in and out, framed by non-hissing 'taped silence'. Dialogue editing, traditionally, must disguise the fact that a real room exists - paradoxically by ensuring that you can't relate its sonic texture of virtual silence to actual silence.

But the strangeness of the nothingness which sounds in Madison's apartment is thick, pregnant, alive. Perversely, Lynch has layered an excess of nothingness, to build a dense and moist bed of rumbling tone which lugubriously bleeds into the air conditioned atmosphere of the cinema. Standard practice in mixdown situations is to audition your final mix against a simulated distant traffic rumble to replicate the urban theatre environment so one can check the soundtrack's clarity. Lynch's sound design privileges the very substance which the soundtrack figures as noise. All the oppressively empty spaces, rooms, chambers and corridors in Lost Highway breathe and heave this nothingness through a network of zones vibrating with noisy silence: the tensile ringing of fluoro tubes, the baritone chorus of central heating, the organific tone clusters of electrical circuitry, the dissonant harmonics of air vents. The on screen world is effectively turned inside out to inhabit the auditorium - a device that perfectly fits a film whose project is to loop back on itself in an unending nightmare of psychosis.

Contrary to Lynch's fawning filtering of art history's radically chic icons, his sound design is sharp and logical. Having visually emptied Madison's apartment in tres-hip neo-Antonioni style, he makes one aware of the absence of objects and the spareness of a space only an architect could inhabit (or a thirty-something musician still living in the designer-80s). Put simply, that low rumbling tone is the aural equivalent of the grimy brown, gun metal and dark olive which suck all colour into their depths. The lighting design and camera work extend this logic, giving us that sublime moment when all space and depth becomes a granular shadow of invisibility as Madison walks into the black hole of centre-frame. In this scene, Lynch employs the perceptual precision typical of Disneyland's design logic in order to convey an existential void - yet he doesn't do it in a literary mode by referencing Satre or Camus. He creates his void as a truly cinesonic moment, born of the audio-visual meld.

I'm being overly precise about this, because everyone and their dog knows those reverberant, booming rumbles that echo from ERASERHEAD to BLUE VELVET and into every 'strange' short film made by every film student in the last 15 years. Like, big boom equals fucked-up mind. In the 40s it was the vibraphone; the 50s, the theremin; the 60s, echo machines; the 70s, the synthesizer; the 80s, big, metallic clangs put through too much reverb - and they all equal fucked-up minds. ERASERHEAD churns the same old romantic cheese by dwelling on weirdo head states and employing dissonance to 'subtly' convey a character's 'otherness', yet the film is nonetheless a landmark in exploring base emotional states through aural abstraction. Still, the question remains - and I'll flag it here rather than completely answer it: what does a big, bad boom have to do with a fucked-up mind?

Essentially, it's a matter of scale. The weight, mass and volume of those big booms convey a monstrous size that intimidate us: we associate those sounds with catastrophe. The big boom replicates sonic occurrences like thunder cracks and rolls, nearby earthquakes and tremors, distant gunshots and detonations, collapsing buildings and crashing cars. Bass frequencies at high volumes physically wrack the body, placing one within a traumatizing field of shock waves. Anyone who has lived through such events can testify to the precision with which a low frequency sound can psycho-acoustically instil fear. But that's not all. The 'feel' of those sounds - ie. their subjective presence within our psycho-acoustic subconscious (our own moist darkness where most sound seems to operate) - uncannily links to deeper neurological states: headaches, migraines, hang-overs, stress, etc. The Nutty Professor stages a gag we know too well: Jerry Lewis with a hang-over endures the subsonic detonations caused by his students tapping pencils on a desk and chewing gum. The infamous Chinese Water Torture induces a similar state by fusing surface tactility with aural comprehension to make one feel that each drop of water falling on the forehead is like a dynamite blast inside the head. All in all, when the cinema employs the big, bad boom, it is resorting to cheap carnivale manipulation - which always works. As an inheritor of Disneyland's postmodern apparatus of apparitions, David Lynch's sound design knows this well.

Interestingly, Lost Highway is complex and subtle with its transformation of the standard series of single booms into dense, low frequency drones. Apart from formal differences, acute narrative differences are built upon these drones. Booms are percussive - they are discrete events which dramatically punctuate a point within the narrative; drones take the vertical energy of those moments and flatten them into a horizontal spread of de-dramatized continuity. Monotonic drones always create tension because time passes while the 'music' seems to be standing still. It's like the gears are locked and something is stuck.

Lynch's sound design dissolves the archly dramatic boom into a tactile, sonar tempura which coats the darkened chambers of Lost Highway. As such, he inverts the terminal lethargy of 'deep and meaningful' chamber room dramas - where people walk in and out of rooms and just say stuff - into latent paroxysm. For some people, Lynch's sense of dramaturgy is thin, mono dimensional and lacklustre. Despite his overt postmodern playfulness, this is true - yet combine that very dramaturgy with a sound design that is thick, multi dimensional and gleaning, and you have something far more psychologically involving. Lynch sonically renders dramatic hollowness as a seething container of otherness, heightening our anxiety while we watch what on the surface appears to be undramatic events.

Quite possibly, you could get a talky 'quality' film (pick your own title), remove all the string quartet music, layer and remix all the humming background atmospheres, and a cliched mid-life-crisis drama may devolve into an aural whirlpool of psychosis. How? The on-screen dramatic points would not disclose any clear psychological motivation behind the dialogue exchanges, and the absence of music cues employed to enhance those dramatic points would disorient and confuse one's ability to 'read' the characters. This is exactly what happens through most of Lost Highway: you simply don't know whether anyone is telling lies or truth, or why they would be saying what they're saying anyway. I point this out because Lynch's sound design is working in concert with a specifically generated dramatic scenario that in the end gives us no clear insight to any character's psychosis. Most 'Lynchian' copies try and render their scenarios meaningful and explicative - which goes counter to the big booms and rumbles they employ purely for stylistic effect. Their 'otherness' is gratuitous, ill-defined, unconvincing. Ironically, Lynch's postmodern effect is clarified when copies pale next to his own authorially suspect work. Comparatively, those copies are safely illuminated walkways running along council-developed suburban creeks to David Lynch's aurally chiaroscuro Lost Highway.

Text © Philip Brophy 1997. Images © David Lynch/October Films/Focus Features/Universal