Where Sound Is

Where Sound Is

Locating The Absent Aural in Film Theory

Sage Handbook of Film Studies, Sage Publications, London, 2008Was there ever such a thing as silence? Surely only the mind could project such an existence - a mind with shrunken ears and swollen brain, cloistered in the concert hall, the opera house, the theatre, the library. That brainiac never experienced the rowdy din of consumption that defined the 'sound of the crowd' excited by the multi-media explosiveness that follows the morphological slip across two centuries from slide lantern lectures to carnival phantasmagoria to silent movies with live accompaniment of all kinds to that thing people finally call 'the cinema'. No, there was never silence; there has only been the deluded desire for silence. That wish for wisting the masses, their machines and their mania cordoned off the cinema to welcome authors, librettists, playwrights - respected soloists of silence - and disallow any noisemakers during cinema's so-called formative era. Thus, silence was born as a denial of the audience and the auditorium - words whose etymology need only be pointed out to the dumb. This is the true abject silence of 'so-called silent cinema': a silence held by the mute repression of describing these multi-media maelstroms at the time which no sophisticated writer would bother to note in any way save for pretending it didn't exist; a silence framed by the problematised historiography that places Muerbridge and Porter in a mime puppet show to demonstrate the magical ocular invention of cinema. It's the same silence that researchers have progressively been impelled to 'sound out' by piecing together mood music cue folios, hyperbolic trade magazine ads, faded photos of piano players. But despite the irrefutable evidence provided by historians like Rick Altman in his ultimate summation of the genesis of cinematic audiovisuality in Silent Film Sound, it is a sonorum we will never experience, let alone hear.

This impossible reverie and the fait accompli of its a-sonic reality has created a gravitational pull back to the silent cinema again and again. Maybe there we can rewrite film history and get it right this time; maybe there we can find some Darwinian proof to bring back to the Society of Film Scholars to issue their silence as fundamentally flawed in its false inscripture of the audiovisual medium of cinema; maybe if we keep mounting 'authentically verifiable' versions of ye olde musical accompaniment to faded and restored film prints this history will come to life for everyone. Maybe, maybe, maybe. For all the amazing research and presentations that have been forwarded in the field of silent film sound/music over the last twenty years, one can't help feeling it falls mostly on deaf ears. Film sound/music is still treated as a 'special issue' as if its destabilised reprioritization of the aural is a disability, requiring a special rampway up into the heads of film theorists, historians, academics and editors. The point many are likely to miss in Altman's exhaustive Silent Film Sound is that his tome's intention for cinema to be "reconfigured through sound" invites its manual to be used for extending all possibilities of sono-musicality in the cinema from the silent period onwards. I prefer that 'Silent Cinema' be renamed 'live cinema'; and that the advent of sound cinema to be regarded the birth of 'Dead Cinema' (more on this notion later). For some, history is a virtual time machine: cosy and baroque just like the chair Rod Taylor rides in The Time Machine. For me, history is a giant metallic mobile-suit with internal psycho-neural fluids, just like Shinji rides in Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Let's take a trip.

Outside the movie theatre …

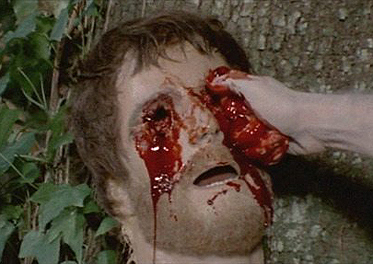

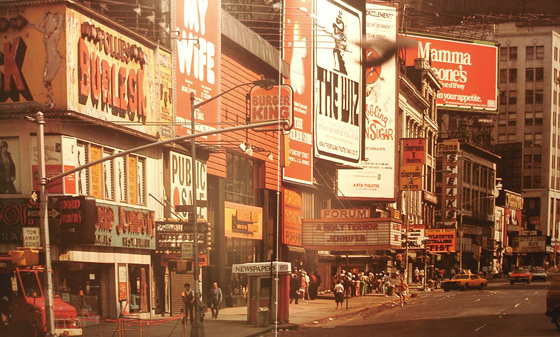

I was once transported to the Nickelodeon of Neverland. It was winter 1983. I took in my first triple bill at Times Square, New York City. Piranha II – Flying Killers, Cannibal Holocaust and Pieces. The audience yelled through the whole picture, men and women shrieking “muthafucka!” a million times over. The movie was turned up so loud to get over the crowd noise that any gun shots (or chainsaw sounds) were even more distorted and gut-punching. Come intermission, the lights went up, murky early 70s slide advertisements were projected onto the screen, and about twenty ghetto blasters were instantly cranked up high. Humongous security guards idly paced the downstairs aisles, slapping baseball bats in their fat hands. The air smelt of rancid butter. I was in heaven – and it was as noisy as hell.

For the intelligentsia, early 20th century cinema was nothing but noise. The possessed patrons, the infernal machinery, the diabolical din of it all was everything the angels in the wings of theatre had strived to obliterate. The baseness of cinema would have been as attractive to theatre critics then as death metal mega-bill concerts would be the concert music critics of today. The noise of production and consumption is a hallmark of 20th century exchange, typifying industrialization as a cacophonic manifestation of the warping of time and speed that increased manufacture brought to bear on modernist economy. Audiovisual entertainment of the originating milieu was bound to be similarly ‘noisy’ through its hybridity, malleability, compaction and condensation of all traditional art forms. The modernist tropes of collage, fusion and rupture quite organically increased the aural and the sonic primarily through a ‘live multi-tracking’ of events and occurrences. Voice, sound effects, music, atmosphere, and a mix of controlled and unplanned circumstances fuelled equally post-vaudevillian and proto-cinematic monstrosities, creating audiovisual chimera whose sensational effects and spectacularized presentations embraced the essential quality of noise.

While noise today instantly evokes some kind of aural sandpaper on the ear or fingernails on the blackboard, the automatic presumption that it is merely irritating and aggravating clouds clarity of its defining attributes. Irritation and aggravation are only effects on the auditor; they do not describe the cause or site its circumstance. Furthermore, negative response to noise is mere cultural conditioning: lots of people love noise – but they’re not writing books about it. Most writers of any persuasion (but especially film theorists) label anything ‘noise’ that does not conform to their pre-fab sound world, rendering their consequent arguments thin due to the dismissal of a wide range of sound and music purely on aesthetic terms. Beyond aesthetics, three key characteristics can be used to discuss noise on fuller terms:

(a) Noise is an interruption to some pre-stabilized continuum so as to produce an interference (e.g. an industrial garbage truck collecting bins in the middle of the night while you try to sleep)

(b) Noise is the disproportionate, unbalanced and/or emphasised conveyance of sound so as to produce distortion (e.g. a voice as heard on a security guard’s walky-talky weakly receiving the broadcast signal)

(c) Noise is the multiple voicing of discrete contents thereby overloading communication so as to produce incomprehension (a restaurant with wooden floors and high ceiling full of people talking over background music)

All three modalities of noise might be irritating and aggravating, but their ‘voicing’ as noise is determined by entirely different modes of production, acousmatic factors, psychoacoustic parameters and environmental conditions. To not hear difference in these voices clinically impairs one to then talk about film sound specifically, cinematic realism generally.

Interference is a ploy used on the film soundtrack to agitate and induce anxiety directly within the psychological corpus of the audience, in preference of having a character express dialogued angst about how ‘anxious’ they feel: from the slamming cupboard doors of Patty Hearst to the rattling aircon ducts of Resident Evil. Distortion is the prime operational method for orchestrating shifts between subjective and objective perspectives on the film soundtrack, in preference to voice-over narrating and ‘cut-to-thinking-close-up’ signage that acinematically directs audiences into reading shifts of perspective: from the screeching aviary of The Birds to the smashed-up toilet of Punch Drunk Love. And incomprehension is the bold tack taken in having overlapping dialogue, densely mixed location sound and/or surround-sound spatialization bombard the audience, creating an excess of information that renders the audience incapable of discerning singularity and distinction: from the pathological yabber of California Split to the vocalised schizophrenia of Doctor Doolittle. The innumerable film soundtracks from around the world – mostly modern, some postmodern, none classical – that use these ploys have progressively been outweighing those quaint, humble chamber dramas of the human spirit which quietly whisper to the intelligent cultured film critic: cover your ears and they’ll go away.

Wake up: they won’t.

Outside the concert hall …

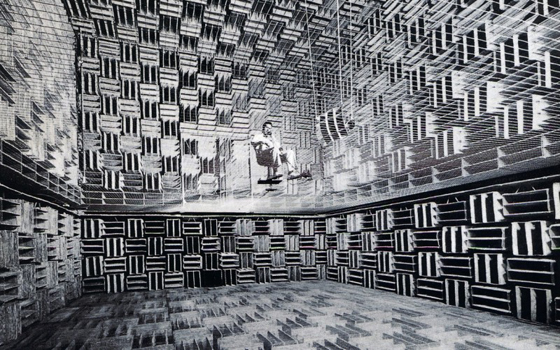

When John Cage calmly noted from his anechoic chamber in the 50s that silence does not exist, he intended to welcome all sound through the liberating act of listening. But prior to his ‘soft-core sonica’, the Futurists in the 10s ferociously forbade silence to exist. Their ‘hardcore sonica’ in the form of intonarumori – literally, ‘noise-makers’ – were designed to celebrate and symbolize the pervasiveness of noise in the then-recently advanced push of the industrial era. Cage adopted the stance of the Buddhist monk which you still find standing at intersections of central Tokyo, engulfed by more scurrying people than there are ants in a sugar mill. Peer carefully at those monks and you can see their lips barely move: they’re chanting a mantra of silence that erases them from their surroundings. Cage’s idea of silence evokes the calm in the storm as a means to be at ease with the world of noise that encases any modern metropolis. The Futurists wanted to both be embattled by noise and to bombard with noise. Tonal terrorists, they heard leit motifs in industry, symphonies in war. Opposed yet conjoined, Cage and the Futurists were engaged in profound acts of listening. Though they never directly addressed the cinema, their poems and polemics concurred and coincided with the transition from noisy silent cinema to noisy sound cinema. Their wild ideas and notions are exceedingly more applicable and relevant than the ear-muffed sensibilities of critics like Bazin whose contemporaneous writing on cinema was and remains entirely out-of-synch with the cinesonic.

The polarities of soft-core sonica and hardcore sonica are continually marked on the film soundtrack as states of existence within which one perceives audiovisual modulation. Some films attack with their soundtrack in order to corporeally, viscerally and materially ‘unsound’ the audience and shock them (the hardcore sonica of Electric Dragon 80,000 Volts, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Hail Mary). Other films generate an aural excess through their soundtracks in order to create a detached, divorced or existential state that ‘disquiets’ the audience and freezes them (the soft-core sonica of Kaidan, The Convent and Taxi Driver). And of course some films shift between these polarities, or start at one end to progressively move to the other. These distinctions are not evidence of a simplistic binary of passive/aggressive stratagems employed in cinema, as both deal with notions of noise. Rather, the hardcore/soft-core turbulence of aurality can be parlayed as variable ranges within key dynamic forces of audiovisuality in cinema:

(a) score production & music phonology: between the live encoding of an acoustic time-space continuum, and the fractal fragmented multi-tracking of post-musical detailing

(b) sound design & spatialization: between the multi-miced on-location mix and capture of actual sound-spaces, and the post-produced highly-processed remix and rendering of artificial surround-sound zones

(c) sound-image conflation: between the synchronous/plausible/compatible spectre of ‘naturalism’, and the desynchronous/irrespective/incohate manifestation of audiovisual simultaneity

(d) psychological audition: between the symbolic/linguistic coding of musical themes to represent a character’s emotional state, and the sono-musical atomization of musical substantia that externalizes the interiority of a character’s disequilibirum

But music, you might offer, has been doing all this and more throughout the cross-wired narrative histories of opera and cinema. True it has. But we also have a century’s worth of composed sound and folk musics that have rejected the harmonic dogma, linguistic system, authorial manuscript and conducted control of music as it had been defined by the end of the 18th Century. The Futurists took to the factories to score sirens and machinery to ‘sing’ the praises of their acoustic reality. Cage placed mics on the street outside the concert hall and ‘mixed’ his acoustic reality into the musical decorum inside. The 20th Century witnessed a lapse in faith of music as stricture and scripture: its written word was deemed incapable of even poetically and metaphorically evoking the complex frequencies, saturated timbres and dense orchestrations of the world of sound which were transforming the act of listening and the boundaries of the acoustic with far greater acceleration than any preceding epoch.

Music has become Latin: a dead language.

Outside the song …

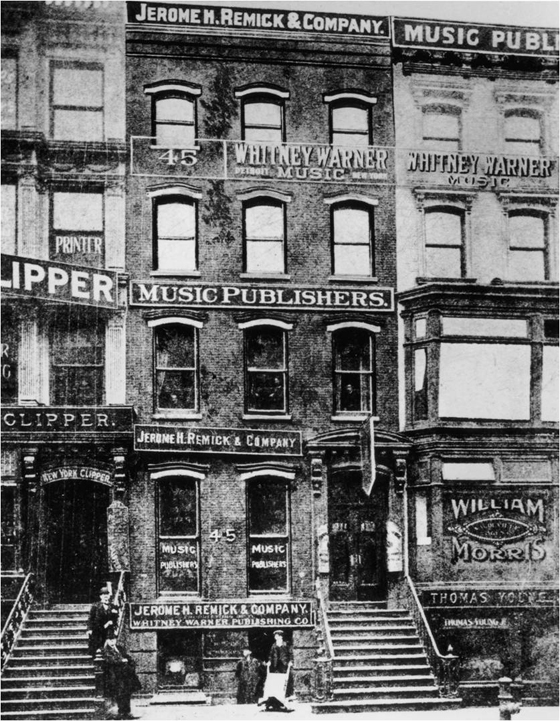

Much writing on Live Cinema (so-called ‘silent cinema’) emanates from the American multi-mediarization of Tin Pan Alley’s (c. WWI) advent of pop music commodification, and from there traces notions of formalized, codified and pre-designed ‘musical accompaniment’ into the ‘classical American film’ so as to site a penultimate cine-text for music in Dead Cinema (so-called ‘sound cinema’). It’s a great place to start but an awful place to end. It traces the noisy birth of Tin Pan Alley – where tune salesmen beat tins to drown out the noise of their competitors – to the induction of that ‘song noise’ into the live eventfulness of the Nickelodeon and dramatic shorts – where rowdy undisciplined ad hoc connections of over-communication were fostered – to its education and maturation in silent, dual-format and synch-sound features – where music became the ‘film score’ authorially inscribed by departmental authority of the studio system’s logistics. This is a life cycle of song more than a song cycle of life. It ends on a flat note: Dead Cinema is the successful erasure of serendipity, simultaneity and sono-musicality in the narrowed name of art, craft and language. The growth from ‘song noise’ to ‘film score’ for many is the attainment of great sophistication. But maybe a lot was lost in the transition from purchasing sheet music to purchasing a movie ticket. The movie experience of music come WWII amounted to a museographic display of the skeletal remains of musical ingestion – relabelled ‘musical accompaniment’ – that signposts the regime of Dead Cinema.

This is not to territorially embrace the arch conservatism that clutches theatre’s ‘living art’ as means of denigrating cinema’s technological power of representation. Moreso, it is to point out that music – that ‘sound of Latin’ – as analyzed within the classical Hollywood film text is bound to never venture into the 20th Century expulsion of musical language as a practice ill-equipped to signify the times. Plenty of pianists write about cinema and music. But where are the trumpet improvisers? The electric guitarists? The drum machine programmers? Where are their critical voices and their counter-texts to the classical texts? What is cinema to their ears? Nor is this to denigrate the canonical findings of audiovisual narrative complexity in American films up to and over WWII. The critical problem that persists – and is seemingly forever side-stepped with incredible deft – is how does one move from Dead Cinema into, well, whatever happens after that?

The answer is not so difficult to supply. Cinema as we speak is a machine of transcendence. It has so thoroughly mutated it bears little relation to its genetic origins despite the coding, clothing and costumery it salaciously wears. Only a fool today would connect a kid with scraggly long hair and beard to the counter-cultured delirium of the 60s. Only a fool would think that The Lord Of The Rings is grand cinema, or that Iranian cinema is the hope for global cinematic humanism. In defiance of all semiological appearance, cinema has become a choral coven of Otherness: its audiovisual miasma of form and style is a completely reanimated corpus of Frankensteinian design. In 100 Modern Soundtracks I have used this notion to demarcate the Modern Soundtrack as a means to hear the death rattle and raspy breath of Dead Cinema and its attempt to breathe through the soundtrack. The Modern Soundtrack is the triumph over the colonization of music and its striated utterance in the classically mixed film in Dead Cinema, celebrating the collapse of music back into the noise from where it came. And it is this rebirth as a Possessed Cinema (so called ‘modern cinema’, sometimes labelled ‘contemporary cinema’) wherein sound – that’s anything that quivers on the soundtrack irrespective of its nature – dynamises and energises audiovisuality beyond structural, categorical and ontological paradigms, and into dimensions of illegibility, irreducibility and confoundability.

You know something’s really dead when you proclaim: “It’s alive!”

Outside the musical …

Just as the possessed speak with voices ‘from beyond’ both themselves and their terrain, so does Possessed Cinema import, receive and attract music from beyond the film score. This is where music pre-exists and counter-exists cinema, defining ‘musicality’ as not simply the figuring of notes to express music, but the source from where music comes and the place where arrives. Key modes of musicality would be:

(a) the phonological – where music is transformed through its rendering and afforded repeatable listening and consumption

(b) the radiophonic – where music is conducted and replayed in open absence of visuality so as to narrate rather then describe or evoke

(c) the broadcast – where music enters multiple and contrasted spaces simultaneously to instigate random and previously undefined presences

(d) the ambienced – where music is filtered and combined with existing environment acoustics so as to create states of distracted listening.

A composer cannot simply ‘write’ music and have it convey the effect of these modes of musicality. Such authorial acts would be delusional – as is most film music that attempts to be something (to voice a musicality) it isn’t. To hear the precise aura of these modes of musicality means displacing the composer and the film score, and welcoming all the zones and realms from which music emanates. Possessed Cinema’s soundtrack necessitates tracing how music bleeds into spaces and places outside of its origination. Hence, pop songs are welcomed for their infection of the soundtrack and their shredding of the film score. From American Graffiti to Amar Akbar Anthony to An Independent Life to Sign O’ The Times to Furi Kuri, this is precisely where we can hear cinema “reconfigured through sound” as Altman dreams – and it is not surprising that these importations of music and song ‘from outside’ echo the same mechanisms inherent in the Nickelodeon phenomenon.

It is equally unsurprising that in the quest to sanctify the film score during Hollywood’s golden era as the fundamentalist writing of music for cinema, the Musical was consequently left to wither and wander destitute, demeaned and defrocked throughout the 60s. The Musical then gets pathetically recouped as realism (the Cabaret effect) or dressed in drag (the Rocky Horror Movie Show effect). Yet both tendencies return to the Broadway Musical in desperate cling to the ‘song writing craftsmanship’ of the theatrical musical – the former in sway with a Jewish excavation of Berlin decadence during the 30s, the latter in embrace of a Gay adoration of the B-Grade American serial from the same era. Either way, the Musical is acknowledged as a hull of its former self, now emptied and ripe to be transfigured as camp in reinforcement of its voice as ‘untrue’. Like old clothes in a second hand store, the Broadway Musical is the dressing-up of musicality from the past. The ultimate irony is how dated it is to buy old clothes that look new and well-kept, when all major global fashion companies are selling distressed denim that is brand new but made to look like it's from a second hand store.

More in synch with the times are the many films of Possessed Cinema that are boldly emblazoned with the afore-mentioned modes of musicality. A phonological musical is O Brother Where Art Thou?, where the soundtrack inter-textually depicts music, anthropologically sifting through palimpsestual recordings to site the film’s setting in a bygone era of technology. A radiophonic musical is Pulp Fiction, where songs are plucked from the radio of the mind, and freewheelingly distributed throughout and without the diegesis and its multiple stages. A broadcast musical is Stand By Me, where memories of songs return to haunt unexpected locations, transporting one back to lost moments of song consumption and enjoyment. And an ambienced musical is Heat where no songs are sung, yet they are ‘sounded’ through their tonal backgrounding of existential drama, creating scrims of instrumental song to meter character. All these films and many more place pop music – its recording, its distribution, its consumption, its archiving – centre-stage on the soundtrack. Score composers like Ennio Morricone, Henry Mancini, Michel Legrand, Quincy Jones, John Carpenter, Ryuchi Sakamoto and John Brion in fact don’t do ‘film scores’. Rather, they respond to how music beyond the cinema conducts them into sounding their scores as documents of song noise. In doing so, they openly foreground how film music is produced in this Possessed Cinema era.

It is neither composed nor experienced in silence.

Outside the body …

I mentioned earlier that cinema now is a machine of transcendence. From being live, to being dead, to being possessed, its trajectory is one typical of most art forms. This model is not dissimilar to the common notion that the arts move through primitive/classical/modern phases, however the transcendent aspect of cinema is a salient difference. Recorded media upset the notions of art forms which reach their apotheosis purely through form, because rendered representations simulate form to then repeat the pre-rendered cycles of form. Cinema is a fractal network of such renderings – its time line of plastic developments in cinematography, production design, acting technique, film score and sound design is not singular and synchronous, but multiple and asynchronous. Peaks and troughs of each plastic art in cinema rarely coincide, characterizing its development as transhistorical (hence the ongoing problem in cinema’s historiography). This innate multiplicity of plasticity constitutes the metabolism of cinema: the calculable rate at which it digests and recycles its own internal energies. Being merogenic (comprised by segmented arts and disciplines uniting to form a complex aggregated form), cinema is bound to reinvent itself through the sheer dynamic principles of its existence: it will always be becoming something other than itself.

Pertinent to our discussion here, the transcendent state of cinema due to its merogenetic structure and its metabolic momentum is particularly – possibly fundamentally – governed by how sound and music exist within the cinema as a plasmatic energy. This assertion is less a concoction of mystical biology than it appears. Some prime distinctions between sight and sound need to be recalled here:

(a) the act of seeing involves the self witnessing that which is before one’s eyes, requiring the viewer to direct and control this act so as to see what is in front of one, thereby always qualifying ‘the seen’ as something outside of the self

(b) the act of hearing involves the self auditing that which is around one’s complete body, not requiring the auditor to direct and control this act so as to hear what is around one, thereby always qualifying ‘the heard’ as something in which the self is immersed.

Put bluntly, I can only see what’s in front of me; yet I can hear everything in front, behind, underneath and above me. This means that the complete lexicon of scopic procedure that has been used ad nauseum in film theory is severely problematic if not basically useless. The facile binary notions of on-screen/off-screen, sync/non-synch, compatible/non-compatible, naturalistic/stylized, etc. that have been used to fix the aural to the visual as if they are structurally dependent on each reduces the compound ‘architecsonics’ and negates the immersivity crucial to our inhabitation of acoustic reality. How a film theory can even begin to address identity, psychology and spectatorship without distinguishing between sight displacing the self and hearing incorporating the self is a frightful indication of the ocular fascism that strangles audiovisual discourse. Just as the written word ‘cat’ and the spoken word ‘cat’ have no correlating semblance bar their abstract attachment, so too do sound and image entail no essential co-determining relationship in cinema. They have simply been placed there, and once placed, they co-exist. Live Cinema knew this – formally, conventionally, technologically. Dead Cinema denies this and attempts to neutrally unify sound and image as if the creation of the soundtrack dictated audiovisuality as locked, tied and bound as the optical printing on the side of the film strip. Possessed Cinema unleashes sound from image, returning it to unpredictable apparitions of ethereal, fluid, porous and transparent coincidences. A full awareness of audovisuality’s capacity to generate serendipity, simultaneity and sono-musicality is virtually absent from film theory as we know it. Comb the canon of film theory from the last half century and try and find mention of how cinema reconstructs the act of seeing-in-front while hearing-behind – an activity in which we are engaged every waking moment of our existence.

Not a single strand comes up, because film theory is bald.

Outside the microphone …

Just about every film theorist has seen the inside of a film camera. They’ve also been in a bio box and witnessed the mechanisms of film projection. These revelations of the mechanical corpus of cinema would likely have taken on a near-mystical aura, reminding one of how these clunky, clacketty technological apparati are the ungainly means by which the magical moving imagery of cinema comes to life. But I wonder how many film theorists have seen the inside of a microphone? The collected writing on film sound in authoritative ‘books on cinema’ implicate film theorists and historians as somehow imagining that the microphone is a sonic camera: a directional, navigational torpedo of encoding. This is not to mock the technically uniformed. The incorporation of microphones in video cameras is a designed reinforcement of this principle. Lay movie consumers and professional film critics equally presume vaguely that film sound ‘happens’ when the camera is pointed and turned on – a doctrine French cinema has polemically advanced under the banner of ‘direct sound’. Industry-bound sound editors, designers and mixers (in America particularly) join sound to image with fundamentalist zeal, as if to move things slightly beyond, beside or between their ‘logical’ assignation would cause the depicted world on screen to apocalyptically cave in and traumatize the audience. The mania for matching sound to image understandably indoctrinates those unknowing of audio post-production to presume that sound always ‘happens with the image’.

This is all easily debunked. Coming from radio drama and creating landmark radiophonic texts in the preceding five years before he made Citizen Kane, Orson Welles structured the whole film around the microphone, contrary to what history tells us of this ‘hyper-visual’ mythic grail of American cinema. In an early scene, we have a single shot: Kane (Welles) is in the background; Bernstein (Everett Sloane) is right in extreme close-up; Thatcher (George Coulouris) is left in mid-shot. They are now old men, deciding on how to foreclose on parts of Kane’s crumbling media empire. They speak in hushed, halted tones, weary with age, too tired to battle their opinions between each other as they had done for so many years. It’s a classic ‘film as art’ shot historians love – perfect for teaching students (who have watched a million video clips and ads and played a thousand computer games) about the dynamics of visual framing and its effect on filmic narrative. But this scene’s arch framing is there for one reason alone: Kane has deliberately been placed off-mic. In the shadowed distance he speaks; he sounds displaced, distanced, disenfranchised. The radiophonic inscripture of Kane’s voice symbolizes his weariness and his fading existential self as he is framed and mixed between the close-miced close-ups of his two colleagues. Kane then moves forward while talking: as he makes his decision final to sell off shares and foreclose the newspaper of his long lost dreams, his voice becomes clearer. His aural blend into the room resonance has now morphed into a distinctly clear voice that intimates that Kane is accepting his actions.

This moment is one of an astounding number that evidence Citizen Kane as filmed radio drama – counter to the film’s grand status is as a cinematographic text, redolent with visual flourishes that evidence the signature of that thing called ‘Orson Welles’. Welles’ modus operandi was to centralize the microphone: to work with it, around it, beyond it. The fact that this scene uses a single microphone when most other scenes are using multiple microphones to aurally map the scenography as ‘spatialised sound in motion’ indicates Welles considered something as sacrilegious as ‘off-mic’ as part of the sonic palette for the depiction of his cine-world. But perhaps the ultimate irony of how deaf film theory is to the so-called visuals of Citizen Kane is the oft-cited use of low-angled camera angles – the famous ‘shooting into the ceiling’ stylisation that typifies much of Citizen Kane’s mise-en-scene. Those ceilings are scrims: stretched lightweight linen lit to appear like plaster ceilings. And behind them: a strategically placed network of microphones that return the recorded space back into a theatrical space, allowing actors to move in complex configurations in open counterpoint to the camera, rather than being forced to ‘block’ their movements for the camera alone.

This use of scrims is an uncanny recall of the movie theatre screen which hides something we do not see but hear undoubtedly: the speakers. Welles hid his microphones on-screen, as opposed to sending them off-screen. In effect, throughout Citizen Kane, the microphone is always in shot, surreptitiously bending the penultimate law of cinematic form: you can’t have the microphone in shot. Yet Welles is one of many similarly silenced voices who explored how the cinema sets up dialogues with the microphonic. Busby Berkeley musicals have their share of ‘shooting into the ceiling’, but just as Welles literally jack-hammered pits in the Hollywood sound stage in order to angle his camera up, Berkeley just as famously issued his familiar command: “raise the roof”. That was the only way he could get up and above the reverse anthropomorphic ‘human kaleidoscopes’ below. Berkeley’s spectacular musicals not once accepted that song and music was sited within the cinema – upon its sound stage, hidden off-camera, cabled to the camera. Song was the meta-shell for Berkeley’s movies during the 30s, within which he architecturally sculpted staged analogues of the music’s patterns, shapes and rhythms. Everyone, everybody and everything moved in-time to music. Celebrated as uniquely cinematic sound musicals, they in fact wholly disregard the instrument which is meant to have created sound cinema: the microphone. This is not through ignorance or rejection, but as an acceptance of the greater expansiveness of sound into which the camera could only ever peer, rove, track and traverse.

There is much silenced cinema that knows that the microphone need not be treated as a camera.

Outside the reader …

The rise of the tone poem in Romantic music (also referred to as programme music, scene painting and image folios) is a pre-cinematic form of musical narration in its emphasis on evocation, pastoralisation and pictorialism – key devices employed through the narrational functions of the film score. When Liszt’s impressionist tone poem At The Lake Vollenschdat unfurls flurries of chordal trilling of blurred and overlaid tonal keys so as to harmonically simulate the overlapping and self-dissolving shimmering of light sparkles flitting across the undulating surface of water, it only partially uses harmony’s linguistic scripture and readability to effect a state of water-play. Fundamentally, Liszt’s piece is an intuitive and organic algorithmic configuration of frequencies and proportionate patterning that are not dissimilar to the acoustic sound of lapping water as heard near and far from the lakeside vantage point. It’s not as if there are certain notes or collections of notes that linguistically state or signify ‘water’, such as how the utterance of the word ‘water’ will abstractly connect our mind to the idea, memory or experience of ‘water’. Sound’s physical manifestation is the overwhelming of its linguistic analogue, for sound (by which I include music as a subset) becomes language only through abstract metaphor. Music doesn’t ‘become’ sound: it is sound, and the means by which it references, replicates and represents a physical reality will be through a reconstruction of scale, ratio, mass, volume and frequency.

Tone poems of the 19th Century invite one to less ‘read’ music and more ‘hear’ it. This infection of musical composition with the poetic – in opposition to classicism’s crypto-rational ‘argumental positions’ on harmony and tonality – has been embraced mostly as a celebration of the humanist voice encodable within musical composition, hence the heroicism of impressionist and expressionist modes of musical communication. Yet tone poems and their poetic dénouement are more interesting in their narrational grasp of a space, environment or world within which the listener is sited. The hidden irony – in both musical and cinematic historiography – is that while tone poems were adapted as film scores to describe spaces and places, they ended up becoming stages: artificial frames, backdrops and cycloramas. Perceived this way, film scores linked to this tradition (and that’s a lot of film scores) empty the immersive sensational evocation of the tone poem form and flatten its sono-musical attributes into a coded linguistic system. Images of glinting lakes overlaid with trilled piano chords appropriating Liszt’s tone poem over-communicate and audiovisually saturate the spatial realm depicted. It’s not dissimilar to zooming in hard on a reproduction of an oil painting of Swiss Alps in a Swiss restaurant in Nebraska: you're there, but you’re not there.

Film music as delivered by the film score promotes an act of reading: of recognizing, identifying and comprehending music as a ‘post-titled’ layer of signification in the audiovisual text. Hearing is treated essentially as the motor-neurological means to activate the reading. Hence, arpeggiated octave runs on piano in the pentatonic mode ‘means’ light-on-water vis-à-vis the musical etymology strung through Debussy, Sibelius and Liszt among others. It is not surprising that so many analyses of film music reproduce the score’s sheet notation as evidence of the reading required. These are indications of how ‘a-sonic’ the film score is in its formulation and promulgation both as composed art and critical analysis. On the one hand, the recourse to ‘read music’ within the cinematic object via the film score is a well-aimed strategy to dig deep into the film’s intertexual layering. On the other hand, musicological analysis of this type, while working great for classical film texts that clearly demarcate where the film score resides, don’t help us once the film score vanishes, is rejected, doesn't exist or has been deliberately lambasted from the film. This shortcoming of ‘score reading’ laterally enforces a segregation of song, sound and noise from the quasi-literary modes of signification, contributing to the critical silencing of the more abjectly sonic and materially aural soundtracks.

Film music makes plenty of sound, but writing on it makes hardly a sound.

Outside the listener …

Am I really speaking an incomprehensible language here? If you think what you’ve read is an oppositional polemic of unscholarly dyspeptic compulsion, a terse radical diatribe that accuses cinema of being ontologically unfulfilled, you’ve misread and misheard this text. The above-detailed notions of noise, musicality and audiovisuality are not intended to foreground sound as the overpowering of image, as if just because one discusses sound one is throwing down the gauntlet for a territorial duel to defend a definition of cinema. These notions are offered as additional, additive and ancillary textual operations for listening to cinema so as to incorporate such perspectives into the pre-existing and multifarious Babel of critical theory, all of which has some substantive relevance to this thing we call ‘the cinema’.

Italian Neo-Realism, French Nouvelle Roman cinema, American Blaxploitation movies, German early-sound operettas, Russian hardcore porno, Mandarin Huangmei (yellow plum) musicals, Japanese sci-fi anime – they’re all waiting to let you hear their soundtracks. (Even Lynch, Scorsese, Coppola, Altman and Welles wouldn’t mind if you actually talked about their sound rather than through it.) These and so many more moments, movements and mavericks in cinema have been platformed into critical compatibility via the standard respected politicised discursive practices – but they may as well be silent movies for the amount of critical insight afforded their soundtracks. The ‘absent aural’ in film theory is likely the most pervasive, unifying and interconnected critical voice in what has been written on cinema. The positivist push of this text is suggest that next time you get the pang to ideologically dissect a film and hold up your forensic findings for the intelligentsia’s musing, try also listening to the patient you just cut up: their groans could be meaningful and relevant.

Find me a book on cinema that somewhere doesn’t have film frames referenced in its cover design – or eyes, screens, viewers, cameras, projectors. Then find me a book on film sound or music that doesn’t reference ears, sheet music, pianos, orchestras. If there were audiovisual balance in film theory, a book could simply be called “Cinema” – and its cover would be a close-up photo of a microphone. This article is not called “where sound should be”, “where sound can be found”, “where sound is defined” or “where sound can be researched”. The “is” is the important marker – a statement of the prescience, presence and presentness of sound as a phenomenological occurrence.

The answer to the query where sound is? It’s while image is.

Text © Philip Brophy 2008. Images © Respective copyright holders