Sonic - Atomic - Neumonic

Sonic - Atomic - Neumonic

Apocalyptic Echoes in Japanese Animation

Paper presented at The Life Of Illusion: 2nd International Conference on Animation, Japan Culture Centre, Sydney, 1995Published in Illusion of Life 2: Essays On Animation, Power Publications, Sydney, 2007

Introduction

Perhaps more than any other medium, filmic animation - the hysterical unleashing of dynamic movement resulting from the wilful animation of the inanimate - is precisely suited to visualizing the invisible lines and fields of energy which exist in our physical reality and beyond. And more so than the Western animation with which we are familiar, Japanese animation (forthwith nominated anime) is founded on a discursive metaphysical visuality, combining animist beliefs with the medium's fantastic flexibility. While these ideas are symbolically contained in animation from Japan's immediate postwar period, [1] the visual tempo, orchestration and polyphony of post-'60s anime expresses a high-keyed formal interplay between energy and its depiction. Specifically, energy is manifested as the monitoring, graphing and recording of the invisible. Scenes abound where lightning bolts crackle across the screen, breaking up space, objects and people. Very often, this energy comes from a character or from an object recently acquired by the character. Characters' psychological states are similarly outlined by superimposed swirling lines and imported optical backgrounds - visual devices transposed from a long calligraphic legacy in manga. [2] But while manga often used these devices to describe interiority, anime exploits the dynamism of movement to directly and physically affect the real world - to graphically thrust upon us this collision between energy and its depiction. These manifestations of invisible energy are demonstrated by the tangible transformation of the atmospheric conditions of a spatial environment - where, quite simply, a force leaves the body, mind, psyche, soul, etc. and energizes space.

With greater rigour than Western animation, anime employs a concept of linear energy where a causal 'line' of energy is contracted from one point to the next in either dispersive wave form or directed beam form. While Occidental thought will readily exemplify this by analogoue systems like electricity (where man tames nature through 'inventive containment', then allows energy to territorially pass along a controlled line), Oriental thought provides a more immediate and corporeal model: chi. Chi is the energy that exists in anyone and anything. It can be hidden, exposed, tapped, exercised, abused. From the many martial arts through to disciplines like Tai Chi, one channels this energy as a linear flow coursing through the body. This type of transference of invisible chi occurs in a range of energy manifestations in physical reality - from the stature of one's standing body to the slice of the samurai sword to the brush stroke of calligraphy. All are marked embodiments of channelled energy. Each example - the shape of the body, the slice of the sword, the calligraphic character - is a visual mark which is held in place by the latent dynamics of an invisible energy controlled by the body.

Animation is the privileged mode of what I call the apparently-visual world. It shows and reminds us that the world we see around us can be viewed as the markings and recordings of energy fields, transmissions and events - from the concentric rings tabulated to estimate a tree's age to the volcanic formations evaluated to gauge major geological transformations. Once one accepts that all matter is but momentarily held in place by unseen energies and forces whose change alters its condition, then the visuality of things is no more than a slight optical algae: slippery, alive and essentially non-objective. What we 'see' is a disconnected moment from a more expansive and enveloping continuum of events. The animatic apparatus - as a catalogue of machinic , technological and textual effects born of filmic animation - is the prime means by which we can perceive and comprehend the apparently-visual of the medium's verisimilitudeness as the result of frequency relationships in time and space. As I have postulated in THE ANIMATION OF SOUND, [3] the production of cel animation requires all sounds and images to be calculated and engineered according to temporal and spatial ratios of variance. Before any sense, meaning or effect can arise from an animated sequence, time (speed, rate, duration) and space (foreground, background, periphery) have to be arranged, orchestrated and conducted. While this is deftly conveyed through the acute timing and musical command of the wartime and postwar work by the Disney and Warner Bros studios, the medium's potential for further mobilizing and radicalizing the animatic apparatus is not critically evident until the boom of anime in the early 80s.

It is in Japanese cel animation that the dynamic interaction between gesture, event, sound and image reaches an apogee, combining extreme mannerism with post-atomic contemplative states. Consequently, organic energies (air, water, steam, fire and so on) collide with and/or fuse immaterial energies-psychic, cosmic, extra-terrestrial, spiritual, ectoplasmic. While we can easily see, for example, bodies, sword cuts and brush strokes around us, characters in the post-nuclear realm portrayed in '80s Japanese sci-fi animation just as easily sense espers [4] and feel psychic beams whose visual markings (their existence, their presence) exist in an immaterial domain.

Not suprisingly, the sonic - that most invisible yet most palpable energy - surfaces to govern the textuality of anime. Far from having the soundtrack submerged by anime's imagery, image is emersed in anime's soundtracks. This inversion of audio-visual logic (where convention dictates that sound subscribe to image) creates a neumonic effect, whereby sound is both material and referent. 'Neumonic' effects are the law court's hammer bang and radio's electronic whoops that command our attention; theatre's off-stage rooster crow and cinema's off-screen crickets that locate us within the story's time frame. These are not simply 'sound effects' which are interpreted at a base semantic level, but sonic effects which buzz our aural consciousness and signal that a sign is being signified. Our brief analysis of the following scenes from '80s/'90s anime establishes some introductory concepts of (a) how the materialization of energy is narratively foregrounded in Japanese animation, and (b) how such audio-visualizations textually evidence and neumonically signify the nature of sound in our physical reality.

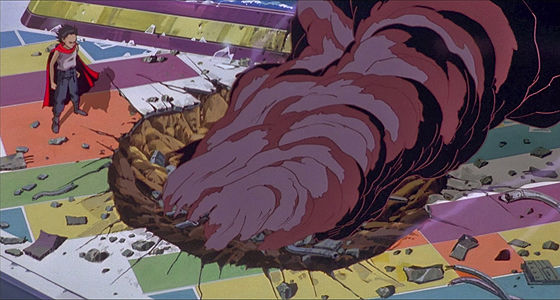

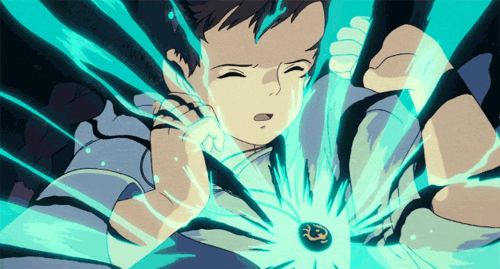

Akira

The character Tetsuo in AKIRA (1987, directed by Katsuhiro Otomo) is a quintessential post-nuclear being - one born of conditions which both redefine our physical reality and allow for the re-invention of the human form. He symbolizes the newness of such a being, and in his naivete and innocence confuses his unique energy with adrenaline power, sending him to a state of abusive excess. His power is conveyed by his ability to exist beyond the putative constrictions of physical existence: he transforms physically; he projects psychically; he transports himself between spatial and temporal dimensions. Tetsuo's anger often erupts in a series of shock waves, hurling balls of energy which emanate from his being and rupture his surrounding physical surfaces. When he is trapped in the hospital corridor and is severely threatened, a psychic ball of energy erupts and pushes out the architecture of the corridor. Tetsuo's destructive bent is rendered by the recordings of power he leaves upon his immediate environment.

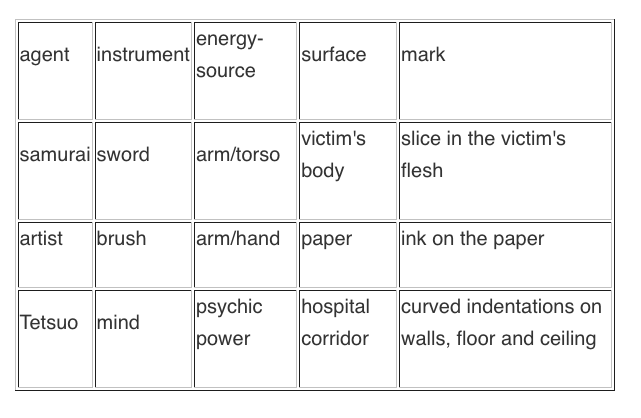

Recall that image of Tetsuo left standing in the hospital corridor, centred by the negative spherical ball which breaks up the walls, floor and roof of the corridor. Tetsuo has encoded or recorded his anger energy onto and into the physical surface of the corridor. This is exactly what happens in the aforementioned examples of the sword and the brush. We could break all these examples down thus:

This model is nearly identical to the often-used characterization of how sound works, where sound waves are visually described as if air is water and the sound waves are like the concentric rings which form when one throws a stone into a pond of water. It is also analogous to the functioning of vinyl recording and speaker design (based on these same principles of expanding and contracting waves of energy) and can be broken down schematically as follows:

Akira

In the process of defining his post-nuclear being, Tetsuo undergoes the transition from dumb punk to psycho-techno Gargantuan. Most of his scenes chart the upscale shift in degree from the human former to the post-human latter. In the first stadium confrontation between Tetsuo and Kanada (and then between Tetsuo and the SOL satellite beam), the transition is symbolized by a fight between the material and the immaterial. This is represented respectively by visual displays of spherical and linear recordings of energy. Tetsuo is a material being battling the purity of a laser beam from Kanada's gun, an immaterial line of energy which slices through all molecular density. Typical of post-'80s Japanese sci-fi animation, characters are defined by the nature, type and level of their energy. All post-nuclear beings have strange powers; the specificity and identity of their powers is the crux of their scenarios.

Remembering that in anime, these powers and forces energize the space within which they occur, AKIRA positions all spaces and environments to capture the recordings of energy waves and lines. Atomic bomb blasts leave huge craters downtown; an esper's piercing scream shatters glass buildings; psychic energy causes subterranean chambers to rise and rupture the overground; etc. At its most extreme, the architecture of AKIRA is rendered not as solid form, but as a network of recordable surfaces. Logically, the soundtrack of AKIRA highlights how energy waves and lines perform in this manner by exploring the various ways that sound can be temporally split from image, for we most notice the effect of sound when it does not obey the constricture of image. In Western photo-cinematic action films, the big boom of a dynamite explosion is always in sync with the visual ball of flame. In AKIRA, the sound of destruction is asynchronous. As a single percussive incident, it is mistimed to the visual moment of destruction; as an aural passage, it is delayed from the visual sequence of destruction.

The SOL satellite showdown exemplifies both forms of asynchronism. When Kanada tries to shoot Tetsuo with a laser gun, Tetsuo hurls an energy ball toward him. As the veins build on his forehead in a spread of humoral tributaries, so does the concrete break up due to vein-like fault lines fanning out as if feeling the shock waves of an earthquake. The synchronous relation between the dynamic events (caused by agent, instrument, energy-source and the mark on a surface - charted above) are thus delayed, extended and established as a running counterpoint to the visual action. Contrast this, for example, to the archetypically Western climax in CARRIE (1976): she twists her neck, eyes the door, the door instantaneously slams shut on cue to a violin stab. In AKIRA, instead of seeing and hearing one simultaneous explosion, we see and hear a gradual build-up of energy, from its projection to its eventual detonation. Following the breaking apart of the concrete on which he stands, Kanada registers the loud explosions around him; but he is then caught off-guard by the silence that follows, as falling pieces of concrete rain down on him. His reactions to the situation are as out-of-sync as the elaborately orchestrated soundtrack.

When the SOL satellite beam is first sent down to the stadium, the audio-visual delays in the Kanada-Tetsuo fight are transformed into a complete dislocation between sound and image. The atmosphere becomes enveloped by a bright blue haze; a deadly silence befalls the scene; a thin ray of light appears; the gravity is altered as small pebbles slowly rise - and then the soundtrack erupts in a series of explosions as the ground is carved up by the beam, as if it is a gigantic samurai sword slicing across the ground. [5] Then here, in response to this audio-visual rupture, Tetsuo beams himself up and past the threshold of the earth's atmosphere. There in space - where no sound exists due to the absence of atmosphere which could audibly register sound waves - Tetsuo rips apart the SOL satellite. Visual explosions appear, but the soundtrack is dead silent. The paradoxical quietness of this audio-visual dislocation is generated by a dimensional split, exporting us into a truly metaphysical realm wherein we can ponder the operation of sound-image relationships within such dimensional warps and shifts. On numerous occasions in AKIRA, the most devastating destruction is depicted in either total silence or with naught but a soft vocal tone or subtle deep rumble. In these scenes, the energy is so intense it appropriately appears to be beyond the recording range of the soundtrack. In anime, when the sound is so severely dislocated from its image, the apocalyptic 'big bang' is nigh but will never be heard.

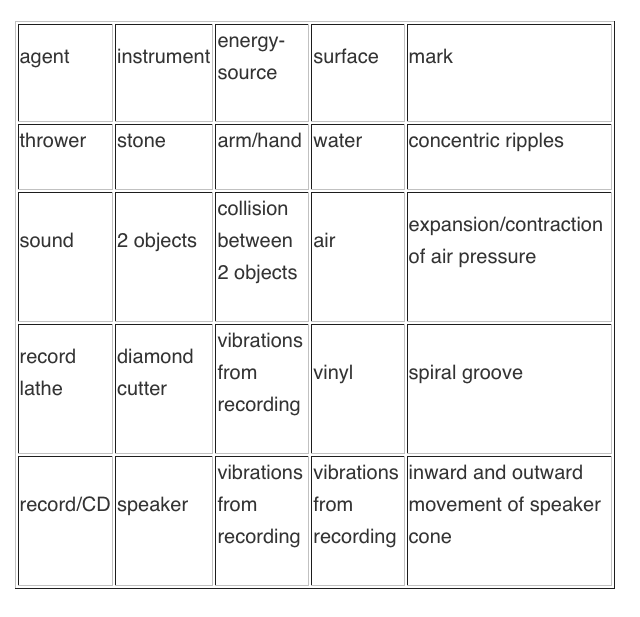

Laputa

The balance of energies - how they lock into and against one another - is a fragile system. While we may intellectually appreciate the relations between microcosms and macrocosms, anime is notable for its respect of the same. Every energy source has its own threshold, its own location, its own environment of manifestation. One slight touch and everything is put out of balance. The apocalyptic finale in LAPUTA (1986, directed by Hayao Miyazaki) pictures this well. The monstrous, archaic construct of the floating sky castle suggests an unworldly presence of power, due to the gravity-defying spectacle of a solid rock castle floating in the air - an environment which also contains its own gravitational force governed by the central levi stone. When Sheeta and Pazu speak the charm of ruin ('Balse!'), they dislodge the sky castle's mystical power core, causing the whole energy system of the massive hovering rock to collapse and uncover the marvellous organic root system which drew life and sustenance from the ground surrounding the levi stone.

Sheeta's levi stone pendant is a miniature version of the sky castle's huge levi stone. This stone not only allows bodies to levitate. It also gravitationally binds bodies to it. As the sky castle falls apart, the inner core of energy - a bright blue spherical apparition - is revealed as the energy ball which attracts all surface material of the island (stone, ground, tress, roots, etc.). Just as the slight alteration of an underground tectonic plate can effect a major earthquake, so does the utterance of 'Balse!' cause the whole sky castle to collapse. Each creates a sonic vibration that unsettles a previously still surface - like the stone thrown in a pond creates concentric ripples. The sky castle's destruction is a visual rendering of the apocalyptic finality under which many pan-Pacific islands exist: any island enjoys stasis and equilibrium until sonic, tectonic and oceanic waves disturb it.

Characteristic of Hayao Miyazaki's eco-sci-fi, [6] the levi stones of LAPUTA are succinct visual symbols of macrocosmic eco-geological energies which hold the earth in place: planetary gravity, physical density, oceanic currents, and so on. The core levi stone of LAPUTA is remarkably similar to the deathly white orb which opens AKIRA. Each is a ball of energy that disturbs and destroys. In AKIRA, the energy ball sends a series of outward shock waves which raze the metropolis. In LAPUTA, the energy ball inverts energy waves to create a self-contained gravitational force for the floating island. Both are invisible energies which determine the visual landscapes of their environments; both exploit the animation medium's capacity to render such energies visible and determine the direction of their flow.

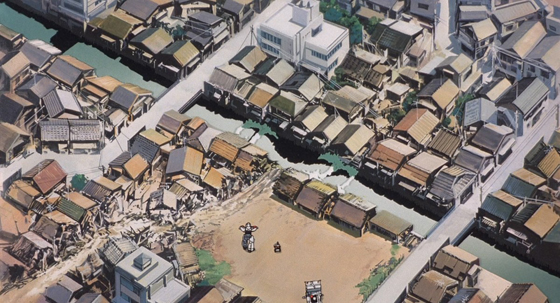

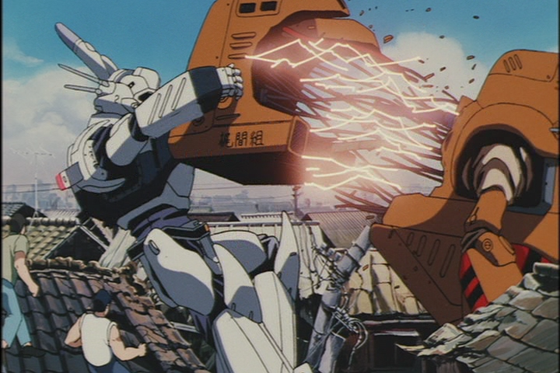

Patlabor

PATLABOR (1991, directed by Mamoru Oshi) features many scenes where re-programmed renegade industrial robots ('labors') wreak havoc by recklessly careering through Tokyo. In many respects, this figure of the gigantic monster or robot trampling the city underfoot fuses the gigantic spectral presences found in yokai folklore (beings the size of mountains suddenly materializing to destroy villages) with the mid-'50s to mid-'70s Toho cycle of monster movies (Godzilla, Mothra, Ghidra, Rodan, Gamera, etc.). Particularly, the stylized Toho movies delight in destroying dioramas of Tokyo again and again and again. The semiotic baggage of Godzilla is too dense to detail here (nuclear radiation/mutation, urban decimation, American imperialism, postwar traumatization, etc.) suffice to say that Japanese postwar entertainment embodies destructive principles and aesthetics, the legacy of its own nuclear devastation. PATLABOR exhibits this base impulse to re-imagine the destructive, wherein the city - its landscape and architecture - is treated as the surface across which an agent of destruction leaves its visible mark. From helicopter view (uncannily recalling the telescopic perspectives of World War II air-borne bombing raids), the renegade labor has carved a line across the architectural order of the city's town planning. Like the calligrapher's ink on paper, the groove cut into the vinyl disc or the film of aerial bombing, its path of destruction is clearly recorded.

In AKIRA, when Tetsuo turns the SOL satellite's laser beam against the earth below, shafts of light pierce the clouds, causing a rain of laser destruction to fall on Neo-Tokyo. Typical of much post-nuclear apocalyptic anime, lines, rays and beams of intense energy randomly fall across a metropolis, causing chaos and destruction, not unlike the infamous black rain of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite the Western ignorance of the subtextual scarring which lines the underbelly of popular Japanese imagery, anime remains remarkably attuned to the effect its past has on its current psyche. Irony is deeply folded into PATLABOR's contemporary image of the city: the urban/domestic elements of police, citizens, robots and criminals are the agents of energy control and abuse. Rather than rays, beams or waves of light and sound carving up the landscape, here it is people and machines that tear the social fabric and architectural blueprint. As Ohta in his Shinohara droid battles the malfunctioning labor, he causes an equal amount of damage. Police and the criminal element wage their war, but the power and energy of each adversely affects the surrounding environment.

Giant Robo

In a sublime fusion of the Gothic with the apocalyptic, an early scene from GIANT ROBO (1992, OVA series directed by Yasuhiro Imagawa) opens with the huge church bells of Paris' Notre Dame Cathedral clanging with the bodies of dead scientists: the death knell of old science for the city of the future. While these bells are not integral to the story of GIANT ROBO, the image of the bell is highly relevant to notions of sound.

The spherical design of bells allows them to resonate harmonically-tuned frequencies, so that sound waves created within the bell generate a complex sonic event which rings the whole bell, causing it to vibrate and send out a clear and rich tone capable of carrying across great distances. In essence, a bell is half-ball and half-megaphone: the dome of the upper-half rings and resonates while the aperture of the lower-half amplifies the ringing. When a bell resonates, it becomes energized by the force brought to bear on it and sends out a series of shock waves. The image of the bell's spherical upper-half is thus remarkably similar in both image and function to the sky castle's spherical lower-half in LAPUTA and the erupting spherical upper-half of the nuclear white orb in AKIRA.

Once the bells of Notre Dame have sounded, an expanding set of shock waves emanates from the central cathedral to eventually surround Paris: as a negative energy field drains the city of power, all lights are extinguished from the centre out to create a black hole. The knolling bells ring across the city and ominously signify the event of the energy drain; the blackout silently and visually follows the pattern of concentric circles which neumonically replicates a bell's own spherical wave formation. Once again, the visual is the recording of energy waves which rupture a material surface. Actually, the blackout is a macro-circle of energy drain that follows a micro-circle or internal circumference of Dr. Shimizu's underground laboratory, which has risen to the surface to create a circular island of black energy, which then drains the surrounding area and later the globe.

As in many horror and Gothic-inspired scenarios, the earth covers the past, the dead and the forgotten. While Occidental Gothic sets its scenes near a graveyard of buried dead bodies who return to life to haunt the living, the 'Oriental Gothic' of GIANT ROBO functions according to a pan-Pacific logic: tectonic plates on the ocean floor are themselves markings of the earth's life in a previous epoch, waiting to rise up and destroy the present through a cataclysmic earthquake. The earth is the past. Dr. Franken Von Fogle - presumed dead and buried in the past - returns to haunt the prosperous city running on the Shimizu drives he invented by literally raising his underground laboratory to the surface to create a black hole of oppression.

My Neighbor Tottoro

Just as destruction can result from an epic drain of energy (prominently figured in GIANT ROBO and in much post-apocalyptic scenarios from the East and the West), creation can embody what would normally be a destructive force. The energy utilized in the advent of either force grows from its opposite. Most examples discussed so far evidence ways in which a surface is ruptured, scratched, engraved, distorted, encoded, etc., by an energized instrument whose vibrations change facets and features of the surface, and thereby the surrounding space. In MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO (1987, directed by Hayao Miyazaki), a key scene reverses this.

When King Totoro wills the tree to grow from the seedling patch, the tree sprouts forth from the earth: the ground is an energized surface which reacts to King Totoro's will and hyper-accelerates the tree's growth. In keeping with Miyazaki's perspective on the role eco-systems play in shaping our environment, the living earth gives birth to a living tree. This bi-polar model of energy flow - that which energizes and that which is energized - can be discerned in the mirroring of the underground root network by the overground branch structure. Here instruments and surfaces are energized by each other. The animated simulation of time-lapse photography portrays the invisible time line of the tree's life-force, thereby acknowledging that the moment of our perception (the 'image' of the tree) is ultimately a mere intersection in another continuum (the 'life' of the tree). As we have uncovered thus far, the apparently-visual world around us can be surmised as the recordings of past and dormant energy fields. The expansive terrain of post-'60s anime also freely inverts this metaphysical precept to project forward and view the apparently-visual as ground for that which might come to exist. Thus, the flat earth is a potential forest; the still pond has subsumed the stone thrown into its depths; a post-nuclear civilization is built upon the craters of death caused by bombs of the past. In fact, these are the key subtexts, commentaries and themes to which drive the bulk of contemporary anime.

But perhaps the most forceful demonstration of this relationship between the latent/invisible/hidden energy of the ground and the manifest/visible/exposed energy of the tree lies in the haunting resemblance the sprouting form bears to the infamous 'mushroom cloud' of atomic and nuclear bomb blasts. Consequently, such an image can cast the tree as violently rupturing the earth, or cast a bomb blast as being part of a life-death cycle for a city. Each are exemplars of the bi-polar energy flow that is - philosophically, at least - accepted as the nature of life more by the East then by us in the West. This scene in MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO is poignant and elegiac, yet it does not shy away from the power of metaphor it employs.

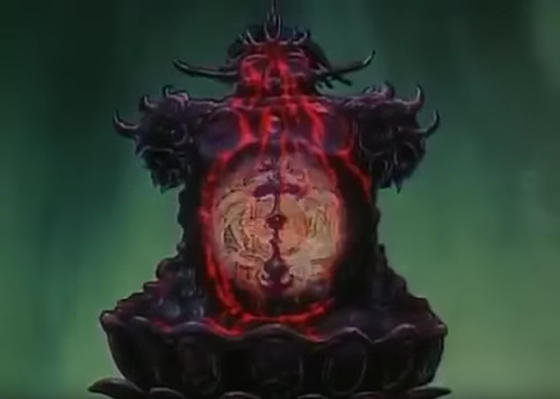

Urotsukijdoji

The sprawling UROTSUKI DOJI (1992, directed by Hideki Takayama, the saga so far numbers nine episodes in two series, totalling just under ten hours) features most of the metaphysical and meta-textual aspects of Japanese animation discussed above: a fusion of dimensions; a collapse of space; an implosion of time; a collision of energies; an explosion of audio-visual conventions; and so on. Also, the numerous apocalyptic closures UROTSUKI DOJI clearly site an ongoing textual dialogue between linear energy lines which carve and slash cities and spherical explosions which engulf and digest complete atmospheres. Working within the operative generic codes of Japanese erotic horror animation, UROTSUKI DOJI is distinguished by two co-joined sonic features which are pertinent to our discussion of neumonic functions in anime.

The first is the interpolation of on-screen dialogue with voice-over thoughts. Logically, a confounding complex of narration arises when a range of characters from different yet simultaneous dimensions psychically communicate with each other in whichever dimension they momentarily reside, as well as engage in their own flashbacks, which occur in various dimensions where further psychic communication is carried on between dimensions. What is particularly noticeable in UROTSUKI DOJI is how much plot and character development exist at this level, giving rise to intriguing narrative implications rarely explored in Western cinema. While the image track maintains a fixed location for a set scene, the soundtrack is fluid and multiple. Voice - inhabiting multiple locations - is the vehicle by which the soundtrack registers dimensional warps and demonstrates the neumonic role of the dialogue.

The second sonic feature of UROTSUKI DOJI is the metaphorical use of sonar and aural figures to shape both narrative and soundtrack. In the film's climactic conclusion, the central character - Amano Jyaku - engages in a dialogue with the as-yet unborn Chojin (Overfiend), who has been transported to the womb of Akemi and left to hibernate in the Osaka Temple. Akemi is suspended in a non-space, hair floating upward, as concentric rings of luminous sound waves emanate from her womb, while maidens chant to keep her alive in the Temple. The womb is a crucial symbol here, being the sonar-tactile environment which shapes human experience to a remarkably sophisticated level prior to 'birth'. Enveloped in such a hyper-sonic domain, Chojin's voice transmits like a telepathic heartbeat across the converging dimensions resulting from Lord Chaos' destruction. At every level, this scene resounds with the sonic. Energy - that essence of the universe which is at the centre of UROTSUKI DOJI's labyrinthine plot - is materially centred in the womb of the unborn, and psychically projected via waves of sound. Recall: the still water disturbed by the catapulted rock; the earth by tectonic fractures; the metropolis by nuclear detonations. Now, the womb - symbolically and neumonically a universal drum of life in UROTSUKI DOJI - is disturbed by the emergence of the Chojin whose birth causes parallel dimensions to cataclysmically fold into each other.

Let us compare this to an Occidental vision of the metropolis' nuclear demise in the live action film FAIL SAFE (1960, directed by Sidney Lumet). The final scene is a montage of still photos of New York married to a continuous high-pitched drone signifying the melted telecommunications between New York and Moscow. Such a finality rarely occurs in Japanese animation, as the soundtrack usually voices, announces or predicts that which shall ensue. Put simply, worlds (including Earth) often end, but music, sound effects and voice inevitably continue past the image, indicating literally or symbolically that life-forces still exist and energy still radiates. The irony that FAIL SAFE surrenders under the light of this comparison is that it attempts to end the world by de-animating both image (as photograph) and soundtrack (as absence of voice, music & sound effect) - which is the exact opposite of the audio-visual fusions which drive much anime. Symbolically, we could liken the cyclical, open-ended nature of Eastern narrativity and its metaphysical dismissal of foreclosure to the acoustic phenomenon of reverberation, wherein the acoustic event always carries past its occurrences in both time and space, and-most importantly-within a frame we can audibly perceive. In terms of anime narratives, this means that their story lines feverishly flow well past our Western barriers of death, matter, and force.

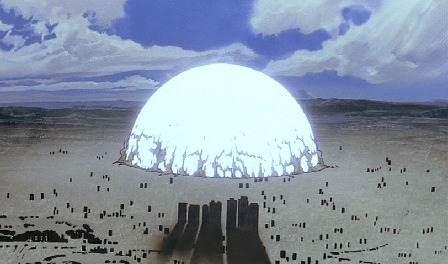

Akira

Somewhere between the audio-visual fissures explored in the endings of both UROTSUKI DOJI and FAIL SAFE is the opening title sequence to AKIRA. A flash appears on the horizon's edge, a huge ball of black energy grows and expands its circumference in sheets of white fallout, gravitating silently toward our location and engulfing the screen in silent white. FAIL SAFE is mute and immobile, incapable of witnessing and evidencing the very destruction which defines the purpose of its story. UROTSUKI DOJI perversely images - excessively, repeatedly, continually - all that FAIL SAFE cannot bring itself to show. Rather than staging apocalyptic scenarios for spectacle, AKIRA positions us to experience a nuclear blast-and to live through it. Its white silence is a deathly visitation in the act of narration: we witness, we die.

Yet, sound-the life of the sonic, the energy of its waves-orients this narration in profoundly mystical and life-affirming ways. The white screen gives way to the standard aerial cartographical perspective; but this time the city is reborn, and the frail remnants of the central Tokyo are held by thin bridges to the surrounding mainlands. The shimmering red and orange, the sinuous bridges, the pulpy morph of Tokyo's remains all evoke the image of a heart. And at its dead centre: the monstrous gaping crater left after the bomb drop which created Neo-Tokyo.

Accompanying this black void is the truly earth-shattering sound of taiko drums uniformly pulsing in huge, single, metronomic explosions. Herein lies perhaps the major neumonic signifier that shapes the fantastic, post-nuclear textuality of anime. The crater we see is the still and dead recording of an energy event (the bomb drop) which has left a physical impression of its energy field (as in the afore mentioned example of Tetsuo's rage in the hospital corridor). Remembering the concave aspects of previously discussed examples of speaker design, water displacement and bell tone, let us now note the structural relationship between a drum skin and its resonating chamber. Once struck, the drum skin is momentarily rendered concave, then convex, then a series of fluctuating shapes between the two, modulated by the proportionate shape-shifting of the drum chamber. In line with the symbolic purpose of AKIRA's political project, the neumonic signification of the figure of the crater can be summarized thus: just as the surface of the drum skin is traumatized by the force brought to bear on its surface, so too does a nation's landscape and its inhabitants suffer an analogous psycho-geological scarring. And just as explosions in Japanese animation are rendered asynchronous, so does the present in AKIRA reverberate its past.

The figures of white screen + silence and black screen + sound stand at diametrically opposed peripheries of animation's audio-visual range, coupling visibility with deafness, and audibility with blindness. They are the edges of the medium, signposted to declare that all spatio-temporal events in between can exist. It should be noted that all audio-visual texts have the potential to articulate radical sound-image configurations (as indeed does momentarily occur in Western live action cinema), yet it is in anime that their conventional fixity is liquefied as a vast reservoir of metaphysical possibilities. Anime's audio-visualization of energized spaces, surfaces, instruments and beings and their resultant neumonic and symbolic effects posits ways in which the latent can be manifested, the potential realized and - most importantly - the sonic visualized and the visual 'auralized'.

Notes

1. Japan's assimilation of Western culture is arguably heightened during the postwar American Occupation. Following America's departure from Japan in 1952, the 60s is marked by refractions and mutations of all Japan had assimilated, giving us their peculiar re-invention of a technological future under an Eastern logic. This period is as vital to the formation of contemporary Japanese culture as America's postwar baby-boom is to its own. It is generally regarded that the animation industry in Japan blossoms with the formation of the independent MUSHI STUDIO under the leadership of Osamu Tezuka in the early 60s (culminating in the successful sale of Tetsuwan Atom - ASTRO BOY - to NBC in America).

2. The acknowledged sensei of virtually all modern manga conventions is Osamu Tezuka. Many stylistic traits of visualizing the inner psychological states of a character were defined in numerous of Tezuka's works between the mid-'60s and mid-'70s like EULOGY TO KIROHITO, MW and BLACK JACK. See Glimpses of a Fantastic Imagination - programme notes to the Osamu Tezuka Retrospective in the 1995 Melbourne International Film Festival catalogue.

3. An investigation of relationships between sound and image as engineered in the process of animation is detailed in my The Animation of Sound in The Illusion Of Life, 1991.

4. Espers is a Japlish term for beings who have extra sensory perception. Such characters - human, cyborg & robotic - have been staples of anime since the early '80s.

5. It has taken a decade for Western photo-cinematic action movies to even attempt this 'demetered' dramatic timing. The explosions of INDEPENDENCE DAY, for example, may have 'plausible' perspectival shifts (the corridor of death down Main Street USA has some slight delays which have been labouriously storyboarded for redundant comprehension), but the orchestral cues persist with moronic on-beat timing. Once again, 19th Century musical conventions nullify the aural power of the soundtrack. Western cinema is neurotic when it comes to music cues - pathologically fearful that an audience won't 'feel' the 'mood' on cue. Anime is subsequently as difficult for Speilberg fans to experience as free jazz is for country & western fans.

6. See Magic, Mayhem & Maelstroms - programme notes to the Studio Ghibli Retrospective in the 1997 Melbourne International Film Festival catalogue.

Text © Philip Brophy 1990. Images © Respective copyright holders