Avant-Garde Rock

Avant-Garde Rock

History In The Making?

published in "Missing In Action - Australian Popular Music In Perspective", Graphics Publications, Melbourne, 1987The idea of merging rock music with avant-garde art is not as far fetched as it sounds. It can be demonstrated even on a mainstream level of entertainment, ranging from David Bowie's acting career to Laurie Anderson's recording career. It is then no big deal these days for most avant-garde artists (whatever their field) to engage in commercial activities, as it is for popular entertainers to venture into the obscure artistic areas. Such moves are indicative of a period that art and entertainment are undergoing. It has been happening for the past eight years and is sure to continue for eight more.

Perhaps we are in what could be called 'the decade of the shift': a time when artistic and cultural activity is generated not so much by a sense of unease or progression (feelings which seem so distant now), as it is by restlessness. These 'shifts' often are primarily motivated by a desire to wander across culture, into new areas, to experiment with the fusion of artistic sentiment and audience expectations.

Culture, of course, has never been able to stabilise or maintain the categorical divisions which it has either inflicted upon itself or been burdened with. Still, dominant views of rock history have generally favoured mythical scenarios, where categories were and are stable. Perhaps there was, once upon a time, an era that did belong to the wild and restless youth. A time when we had something we could call youth, people we could call teenagers. But what was then known as rock'n'roll has now become rock culture. The spirit has been replaced by the problematic, in that whereas rock'n'roll was celebrated or attacked, rock culture is now consumed or analysed. The furore and fever still exist, but they are now pushed through different channels, as a result of the way that rock culture has awkwardly spread itself across society.

The face of rock'n'roll and its mythical identity has grown old and flabby as well as having undergone numerous facelifts, beatings and breakdowns, caused predominantly by factors such as :

1. the diffusion and multiplicity of age groups and social identities associated with particular music styles (parents liking Michael Jackson, while their children like Elvis)

2. the accumulative splintering affect of subcultures changing the meaning of style as unwitnessed by mainstream culture (when is a punk not a punk?)

3. the institutionalisation of the recording industry (now the call of "Long Live Rock'n'Roll" merely equals "Hurray For Hollywood!")

4. the tension that now exists between rock culture and pop culture, exemplified most accurately by the current state of rock journalism (weekly claims of "I have seen the future of rock'n'roll" amount to no more than the belief in the spirit of Rock'N'Roll and the awaiting of its second coming/judgement day in all the pap and pulp of pop).

5. the commandeering of the top 40 as a site for artistic subversion, marking it no longer as a void where content automatically kills content. Did the following groups 'just' make pop records: Kraftwerk, Adam and the Ants, Flying Lizards, Grandmaster Flash, Prince, Sigue Sigue Sputnik - even Bob Geldof, Paul Simon or Samantha Fox?

It is under these such conditions that the rock/art merger occurs. Chain reactions here are never simply chronological or linear and it should be remembered that as these turbulent currents of change scatter cultural barriers in every direction, their related historical sediments are changing too. We are not merely adding new ideas on top of the old; we are changing our perception of what we thought were the old. When rock music is merged with avant-garde art, or vice versa, a mutation is born that gives new and complex insights into both how we interpret art history and how we define rock culture. Rock culture and art history engulf each other in a simultaneous consumption that makes it difficult for us to separate the two from each other as they were. Each area is equally affected by this cultural restlessness, this overcoding of styles and saturation of theories, to produce the phenomenon we call 'avant-garde rock'. As unnatural as it sounds, it does stand as a sure sign of the times.

To find a method of defining rock and art as cultural entities becomes increasingly difficult. Only through recourse to a traditional and somewhat outdated paradigm of viewing history could such a separation be argued. When the broad field of entertainment encompasses mergers of disparate artistic identities (eg. David Bowie and Nagisa Oshima; Debbie Harry and David Cronenberg; Billy Idol and Tobe Hooper; The Dead Kennedys and H R Geiger; David Byrne and Twyla Tharp; Tuxedo Moon and Winston Tong; Psychic TV and William Burroughs) and projects of transnational fusion (eg. Giorgio Moroder and Metropolis; Laurie Anderson and the Top 40; Echo and the Bunnymen and the Drummers of Burundi; Brian Eno with Sony; Run DMC with Aerosmith; Bill Nelson with the Edinburgh Theatre Company; and in Australia, → ↑ → and the Sydney Theatre Company; Ivor Davies and the Sydney Dance Company; and David Chesworth and the Nimrod Theatre Company), striving for purist definitions of art and/or rock can become painfully narrow. As the wires of rock and art are crossed, the result is sometimes short circuits and sometimes surges of power. For the good or bad that is where the energy of avant-garde emanates from and that is where we must go. The avant-garde today, like rock itself, has to be seen in terms not of what it should be, but of what it has become.

There are two possible ways of doing this. The first is to see the avant-garde of rock as a pitiful bastardisation of the original thrust of twentieth century avant-garde art, a cooption of the polemic intensity that motivated the radical nature of its ideas and pursuits. The second is to acknowledge its nature as mutation, as an artistic activity born of visions that arise more from a developed social environment than from a studied historical lineage. The first approach is idealistic. The second is realistic. Avant-garde rock, then, is neither the future of rock'n'roll nor the heir to avant-garde practice. It is simply another cultural mutant that requires reclassification and reーevaluation.

As a category、 'avant-garde rock' is a contradiction in terms. Essentially, the historical tradition of avantーgardism is one of finding new forms and perspectives. The rock'n'roll tradition works on a feeling for formula, reworking and restating existing forms so as to tamper with the surface image while holding respect for the soul underneath. The ’newness' in avant-garde art is absolute. In rock'n'roll it is checked by currency and controlled by transience. By honing in on this tension, we can get the clearest picture of what avant-garde rock might be, by seeing precisely what the relationship between rock'n'roll and avantーgardism entertains and rejects. As a musical style, avant-garde rock typifies the external tension between the conventional and the unconventional in rock. As a cultural phenomenon, it identifies the avant-garde as displaced and misplaced. A lost soul in a historical purgatory the Now.

Avant-garde rock in its current manifestations exists in what could loosely be termed a postーpunk era. For sure, 'post-punk' is as frustrating a term as 'avant-garde rock', but it does point to punk music as being some sort of reference point in the ongoing history of rock music(s) and not as being just another music style. The birth of punk music is of historical importance because it was a musical type that used history (the history of rock) as fuel for its energy, its force and identity. Its statement was in its declaration of itself as present, rejecting the past not merely comprising 'different' musical types and ideologies, but as a period of history: gone and dead; old and used.

Since the punk explosion of 1976/77, rock music has, in the strangest sense, been reborn, relived and rewritten. This has occurred through an ongoing process of rediscovery of the roots of rock and pop. The 'back to basics' manifesto of early punk soon gave way to opening the door into the 1960sーquite an irony, considering the anarchic tone of living in the present that punk so violently championed. This then led to other doors (the 50s, the 40s, etc.) and before you knew it, rock music was a maze of rediscovered corridors with too many doors, with too many signs and too many rooms full of rediscovered values: Mod, Ska, Glam, Psychedelia, Bluegrass, Jazz, Futurism, Soul, Be Bop, Disco, Swing, Funk, Swamp, etc. The term 'post-punk' aptly describes this confused and confusing museum department store resignation, leaving specific definitions and qualifications for those who are willing to grapple with them.

Certainly, punk music, wavering as it did between journalistic dogma and novel bastions of taste made many people loose their appetites for the artistic in music, embarrassed as they were by the excesses of avant-garde jazz rock, symphonic rock and Kraut rock. (Note that even people like Sun Ra, Cluster and Tangerine Dream have since been artistically reclaimed, while people like Herbie Hancock, Peter Gabriel and Yes have since crossed over into mainstream popularity. The times are always a changing.) Those attempts at experimentation were condemned as being either ideologically unsound or hideously unhip. It took at least a full year of the New Musical Express and Melody Maker's lyrical waxing on the politics of punk before many were able to welcome Can and Captain Beefheart as warmly as the New York Dolls and the Stooges. New roots for avant-garde rock had to be established away from the more immediate atrocities, before it was all right for groups to start being progressive in the most menial of ways (which usually meant using a synthesiser on a couple of tracks on side two of their third album). Just as rock music in general is motivated by a guilt ridden view of the past (be it Billy Joel rediscovering the great lost eras of pop, or the Modern Lovers' return to a raw state of musical naivete) the post-punk condition of avant-garde is formed along similar lines. Which is to say that both the avant-garde of rock and the mainstream that it supposedly sallies forth from are equally embroiled in a romanticisation of past periods so long as the present warrants them as being relevant and suitable for associating with. The slogan 'Fuck Art! Let's Dance!' (originally a cheeky quip from Madness which has since been turned into a moronic dogma) still casts a long shadow.

Within a rock context that owes a great deal of its construction and development to the media, avant-gardism loses its essentialism and is instead given an arbitrary smattering of what appears to be 'new' within the rapidly paced yet narrowly spaced realm of the present in rock, or, 'what is in'. As this rock changes and grows, this newness is tied up with being in the right place at the right time. A regeneration and diffraction occurs in Australian avant-garde rock in its relationship to whatever might be happening in England, the United States or Europe, furnishing an ongoing chain of groups that have plugged, knowingly or unknowingly into a whole series of informational tangents that skirt around the globe with a limited life span. In the mediarisation of rock music, rock journalism (in particular the prophetic yet sycophantic tone that the bulk of the English press has fostered for the past decade) is not, as one might think, caught between supporting the old and seeking the new. It is caught between seeking the new and manufacturing the new. The thirst for newness becomes a form of gluttony and obesity in that every 'new discovery' (Salsa, Disco, Industrial Noise, Swamp Music, New Romanticism) only satisfies temporarily. The nature of each newness is never fully evaluated as an organic structure with a continuing life. This leaves an assessment of the situation as a facile identification of everything being seen to be the same: 'the latest thing'.

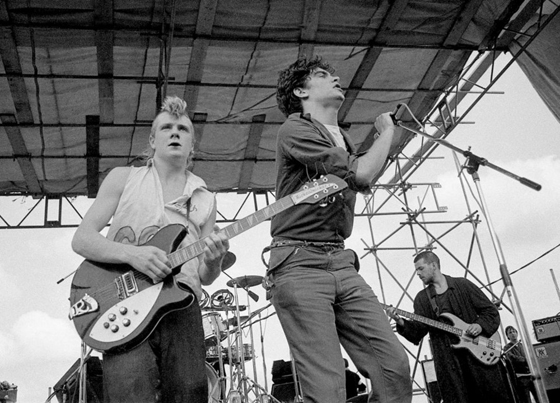

In the golden period of the battle between punk ideology and post-punk aesthetics (mid 1977 to 1978) there were nine major groups which were seminal 'latest things'. Being in the right place at the right time, even though some had been around since 1975/76, they released records which caught the imagination of anyone waiting for punk to develop beyond its birth. Some of their work is as exhilarating now as it was then. Some of them survived by adapting artistically or commercially to change.

The Residents (San Francisco) were and are the quintessential avant-garde rock band because they openly attacked the history of rock'n'roll and its very nature. Apart from their obscurantist theatricality, they are seminal in redefining the cover version as an act of deconstruction and distortion.

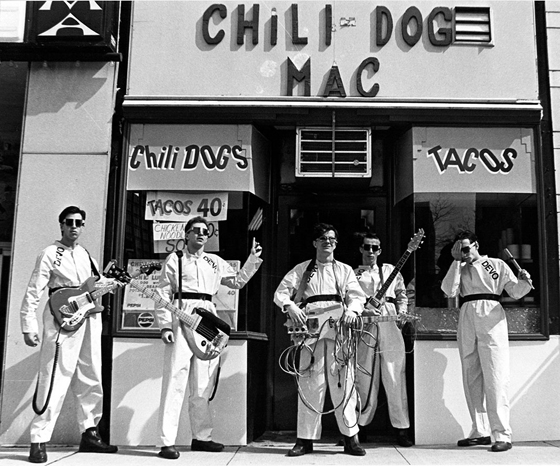

Devo (Akron) were the first band to satirise contemporary middle class American tactic which took the English press quite a while to comprehend. As the Residents are dadaist, Devo are situationist, producing a hybrid form of modem rock that not only bore them mainstream success but also musically exemplified their theory of devolution a theory that rings truer as time goes by.

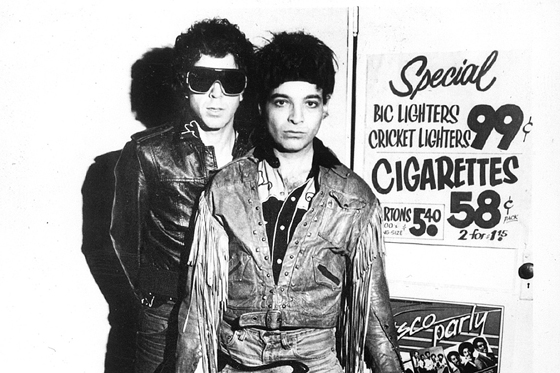

Suicide (New York) applied a performance art perspective on Iggy Pop and a reductivist, electronic perspective on classic rhythm and blues rockabilly riffs to produce a psychotic, angst ridden poetry performance backed by a severe Farfisa drone.

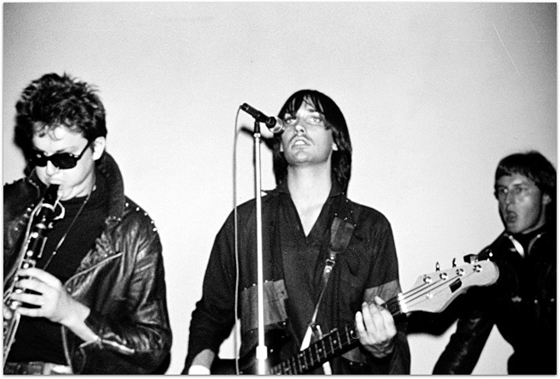

James Chance/Lydia Lunch (New York) and certain offshoots such as the Contortions, Pill Factory and Teenage Jesus and The Jerks, evidenced a total fusion of punk and artiness. In a show of sadomasochistic desire and frustration, they took nihilism to an extreme, producing a piercing, noisy art rock designed to destroy and self destruct.

Pere Ubu (Cleveland) were the most concrete exponents of experimental rock, extending groundwork laid by the Mothers of Invention, Captain Beefheart, Henry Cow and Faust. Not overtly concerned with any precise, presentable image, their innovations were musical and aural, solidly imbedded within rock traditions.

The Pop Group (London) were the most short lived but perhaps the most influential of these groups. Whereas Pere Ubu fractured rock form, The Pop Group did likewise with rock style, creating a reggae dub mix of free form funk in a wild exorcism of soul, history and politics.

Ultravox (London) followed Brian Eno into the realm of post glam electronic dilettantism, overlaying their own pseudo futurist synthrock beats with nightmarish sci fi imagery. (Slightly harder edges were provided by early Human League, Thomas Leer, Robert Rental and The Normal.)

Cabaret Voltaire (Sheffield) fortuitously combined definitive art school pretention (dada, futurism, surrealism, musique concrete, electronics, performance, multi media) and gained recognition through a mystifying yet incoherent mix of such elements, propped up by pedestrian drum machine programs.

Throbbing Gristle (London) were probably the most musically uninspired group, as their confrontational mode of address in performance and manifestos spoke with more intensity than their naive and insipid "industrial" (sic) doodling. However, their influence has been widespread: in the manipulation of sound (volume, texture and rhythm) to generate a physical effect upon the listener and in the obsessively researched presentation of information to overload the imagination and the senses with data locating society's manifold repressions and oppressions.

While rock is stereotyped as "sex drugs rock'n'roll", avant-garde rock's quest for otherness is comparatively detailed and involved. The aesthetics established by the nine groups above were shaped by interests that at best can be described as morbid, macabre and maniacal. Interests that have spawned an immense network of subjects, influences and fetishes over the past decade, such as (in no particular order):

bodily functions, thought control, social demographics, subversion, cultural repression, science fiction, death, medical surgery, forensic science, concentration camps, war atrocities, mass murder, genetics, sex, suicide, psychosis, torture, Satanism, orgasm, sex mania, abnormal psychology, chance processes, eastern religious rites, self immolation, witch purges, sado masochism, state authority and power structures, obsessive sex drive, environmentalism, terminal illness, industrial noise, organisms, biochemistry, machinery, Catholicism, futurism, vocal chants, politics, musique concrete, horror, censorship, factories, electronics, terror, mutants, drug effects, monsters, systems & process analysis, deformities, pain thresholds, freaks, Zen, chemical waste and abuse, anatomy, myths and legends, primal screaming, information control, concrete poetry, media, conspiracy theories, found objects, parasites, violence, aural/ audio research, constructed instruments, pornography.

A regeneration and diffraction occurs in Australian avant-garde rock in relation to whatever might be happening in England, the United States or Europe, furbishing a chain of groups, knowingly or unknowingly plugged into the information stream of those tangents skirting the globe. As such, Australian avant-garde rock groups are abused by internationalist jungle drums as much as they use them.

The seminal period of mid 1977 to mid 1978 had its correlations in Australia. → ↑ → and Jab were performing live throughout 1977, and 1978 saw → ↑ → joined live by SPK, Voight/465, Primitive Calculators and Crime and the City Solution. (Early 1979 saw the first record releases by → ↑ →, SPK, Voight/465 and Whirlywirld.)

Forging into the 80s, a list of subgenres or temporary phases of newness in avant-garde rock can be drawn up as a charter of recent and previous trends. These phases, if not spawning Australian groups at least created a temporary limelight for themselves and their audiences. What follows might appear a bit off-handed (or back-handed), but it is just an attempt to loosely gather groups which in some way have connected themselves to this notion of avant-garde rock. I reserve making value judgements of any one group's merits or lack of abilities because they are all worth listening to - some perhaps not more than once. In my opinion, all these groups constitute a mix of about 80% rock'n'roll and 20% avant-gardism, which leaves me with the question: Is rock'n'roll really so conservative as to be baulked by such an influx of otherness? My listing here really only refers to this oblique 20% avant-gardism in each group and therefore does not account for nor is concerned with the identities peculiar to each of these groups.

Noise was/is seen as the ultimate confrontational device but its exponents often only confronted their own mirrored image smoking nervously on stage rather than an engaged, or outraged audience. Nevertheless, some incredible sonic sculptures were once in a while created. (SPK, Nervous System, The Primitive Calculators, Scattered Order, The Lunatic Fringe, Grong Grong, The N Lets, That Fat Apparatus, Ya Ya Choral, SwSwThrght, Shower Scene From Psycho, Man Made Haze, Bleak, Fragments, War Meat and the Dictator, Vormittaspuk.)

Jazz was on the cards for becoming cool again, although in the context of avant-garde rock it was not a jazz tradition that was carried on as much as it was the playing out of a drama (sometimes well performed, sometimes badly mimed) with things such as expressionism, improvisation, atonality, or old swing movies. Its association with avant-gardism was brief, as the later 80s have been concerned with appropriating jazz under terms of historicism and purism. (Laughing Clowns, Equal Local, Kill The King, Great White Noise, Hot Half Hour.)

Metal (as in sheets of metal, not heavyt metal music) left a quick gleam like a comet flashing by, as creative notions of Futurism and journalistic fantasies of Industrialism struggled and continue to struggle, to climb the hill of novelty to enter the valley of progression. (Whirlywirld, SPK, Dilpidata, Transwaste Orchestra, Skin and Bone Orchestra.)

Synthesisers were synonymous for a long time with the most pathetic notions of avant-gardism, only because the reactionary roots of rock could not bear to be without the phallic support of the guitar and the fantasies of sex, power and adrenalin. Already groups like Depeche Mode and The Human League have been unproblematically viewed as pop groups and not avant-garde groups, leaving us with the difficulty in ascertaining degrees of sophistication in different approaches to employing electronics. (Metronomes, Ad Hoc, White Trash, Informatics, Laughing Hands, Modem Jazz, Donna Detti, David Tolley, Nuovo Bloc, Couch, Artificial Organs, Ria and the Normal, Systematics, Phillip Jackson, Testa Hausa, Transmachine, Patrick Gibson.)

Semiotics lead a life of mystery, clothed in ignorance and misinterpretation by its critics and admirers alike. With too much attention focused on (and alienated by) the theory rather than the application, few people (groups or audiences) could extend the musical relationships of such a practice out past a theoretical elite to groups who weren't as vocal yet produced similar work. (→ ↑ →, Rock'n'Roll Cavemen, Slugfuckers, Use No Hooks, David Chesworth, Essendon Airport, The Connotations, Zerox Dreamflesh, Competence/Performance.)

Cut Up usually and unfortunately owes more to William Burroughs (a glorified cult hero as acknowledged by David Bowie circa Ziggy, Patty Smith circa Horses, Psychic T.V. circa The Final Academy) than it does to Musique Concrete or early (pre-1950) electronic music. As such, it appropriately describes a numbed state of indiscriminate media fragments as a gesture of plugging into a (dated) McLuhan-esque view of the 'global village'. (Severed Heads, Hugo Klang, Go Home To Your Precious Wife And Child, Socciocusus, SwSwThrght, Gestalt, Loop Orchestra, Kurt Volentine, Art Poetry, Ian Hartley, Tom Ellard, Institute of Tonal Generation, Shane Fahey, Rik Rue, Browning Mummery, Bleak, Cutting Up People, Fragments, John Gillies, Mauro Cavallaro.)

The Funk train was the only avant-garde fetish that held enough locomotion to be pushed into a variety of levels of commercial music, ranging from a rejuvenation of dance music to the latest black music providing the historical undercurrent for white rock'n'roll. (Hunters and Collectors, Essendon Airport, Pel Mel, Use No Hooks Big Band, Scratch Record Scratch, Jim (Foetus) Thirwell, Bang, Government Drums, Thin Man Station, The Whites.)

Performance has always been a predominant way of reacting against the neutralised presentation of rock'n'roll (four guys on a stage doing their thing). Performance art, dada manifestos, concrete poetry, multi media events, primal screaming and environmentalist happenings all inspired different groups to stage their events. (People With Chairs Up Their Noses, This is Serious Mum, Jab, John Murphy, Zip Collective, The Lunatic Fringe, Precious Little, The N Letts, → ↑ →, The Incredibly Strange Creatures, Manic Opera, Slub, Jean Paul Satre Band.)

Conceptual (as in 'conceptual art') accounts for certain visual artists who utilised the social form of rock and pop music, especially via the cassette medium, to expand their concerns and deal with a different artistic language. (Slave Guitars, The Anti Music Collective, Media Space.)

Art Rock may have been an old term but many groups were able to experiment with rock form and style without the pomposity the term implied. (Voight/465, **** ****, The Threeo, (Makers of) The Dead Travel Fast, Players With Marionettes, Synthetic Dream, Crime and the City Solution, Slawterhaus.)

Improvisation was an often dogmatic voice due to its harsh reaction against more conceptualised modes of experimentation. Its connection with rock was primarily under terms of spontaneity, although some of these groups worked extremely hard at being spontaneous. (The Even Orchestra, Laughing Hands, Jon Rose, John Gillies.)

Dance has become, for the later 1980s, an even more amorphous term than disco was for the early '80s. Still, some groups experimented with the contextuality of the term (via situationist approaches) and the formalism of the term (via rupturing its recognisable surfaces). (Ian Haig, Severed Heads, Scattered Order, Whaddayawant, I'm Talking, SPK, Gum, Asphixiation.)

Ambient is a broad genre, ultimately determined by Brian Eno's simplistic notion of background music, as he derived it from Satie. Most so called ambient work is a combination of improvised electronic constructions to produce instrumental images, mood music and sonic landscapes. (Chris Knowles, Paul Schutze, Laughing Hands, Scribble, Not Drowning Waving.)

Fusion typifies those bands which have deliberately and specifically worked on a single or number of musical styles to produce a cognitive stylistic/formalist reconstruction. This approach developed in the latter half of the 1980s, concurrent with the heightened awareness of the precise manipulative effect of musical styling.(The Bum Steers, Spring Plains, Mr Bum & Mrs Ruby, Big Pig.)

Unconventionalism is an incredibly stretched way of summing up the unified concerns of the Melbourne 'little bands' network. Following the direction of 1978's No New York compilation album, the 'little bands' strove to bring a harsh and sometimes painful edge to rock tradition without resorting to any form of intellectualism. (A slightly more subdued anti intellectualism was expressed by the considerably more organised M Squared recording studios in Sydney.) (Ronnie and the Rhythm Boys, The Dee Rays, Thrush and The Cunts, Too Fat To Fit Through The Door, Morpions, Oroton Bags, The Hoy Family, Negative Reaction, Height/ Dismay, A Cloakroom Assembly, Splendid Mess.)

Other: Simply, these bands are conglomerations of any combination of the above generic strands. The result, though, is difficult to perceive as a precise or defined identity. However, the general desire to experiment for otherness remains. (Black Swamp Cha Cha, Mesh, Gary Doyle, Toy Division, The Snails, God: The Movie, Hiroshima Chair, Limp, Psy Phalanx, Arf Arf, The Tarax Club, Studio Testing, Cultricide, Mice Against God, Stephen Harrop, Michael Tinney, Kindeebah, Box Music 2.)

Out of these categories it is interesting to note that many of these groups have changed with the trends, or reformed to accommodate them. They fracture their identity as a group or product by: (1) changing their name each time they perform (eg. cut up specialists associated with Sydney's Art Unit performance space and 2 MBS-FM's cntmprry ydtns show); (2) continually forming new groups by shifting key members (eg. Melbourne's 'little bands' network); or (3) working on discrete and self contained projects (eg. → ↑ →). This does not at all diminish their stature or integrity, but indicates the ease with which many people or groups are able to experiment with new ideas as they encounter them. It could be that the avant-garde rock we have witnessed to date might be work in progress for something that has not yet happened. This is especially important considering that very few of these groups have worked with ideas that do not need to live as part of the incessant rock media stream that charters so much avant-garde activity and short circuits it.

Australia is not by itself in this respect either, as witnessed by the imbalance of attention that is accorded to some groups and not others. I list two inconclusive groupings here (in alphabetical order) the first containing fairly well known names in avant-garde and non mainstream circles alike. The second grouping does not receive the same amount of global attention.

1. Laurie Anderson, Cabaret Voltaire, Can, Captain Beefheart, James Chance (et al), Cluster, D.A.F., Einsturzende Neubauten, Brian Eno, Robert Fripp, Phillip Glass, Kraftwerk, Thomas Leer, Lydia Lunch, New Order, Pere Ubu, Psychic TV, Robert Rental, Residents, Throbbing Gristle, Tuxedo Moon, A Certain Ratio, Art of Noise, The Birthday Party, Cluster, (early) Devo, Brian Eno, Contortions, Flying Lizards, Jim Foetus, John Fox, Golden Paliminos, Jon Hassel, (late) Japan, The Pop Group, Snakefinger, SPK, David Sylvian, Suicide, Swans, Test Department, 23 Skidoo.

2. Art Bears, Glenn Branca, Monte Cazazza, Cum Transmissions, Der Plan, Doctor Mix and The Remix, DNA, Faust, Harmonica, Implog, Love of Life Orchestra, (early) Mothers of Invention, Neu, Non, Polyrock, Elliot Sharpe, Sonic Youth, Z'ev, Art & Technology, Beresford, The Bic, Blurt, Ciccone Youth, Tony Conrad, Daniel Stephen Crafts, Ivor & Chris Cutler, Die Todliche Doris, Eazy Teeth, Fred Frith, Robert Gordon, Bill Laswell & Material, Arto Lindsay, Yoko Ono, Orchid Spangiafora, Andy Partridge, Mark Pauline, Robert Quine, (late) Red Crayola, Roedelius & Moebius, Adrian Sherwood, Touch, David Van Tiegham, Whitehouse, Trevor Wishart.

In terms of innovation in rock, and charting new areas for the sprawl of avant-garde rock, there is no real cause for separating the two lists, and indeed, the hipness of the first list may implicate the second as being hipper-then-thou. However, the notoriety the artists in the first list have received has made it hard for the specific problems and attributes of the second list of artists to be discussed. (I would argue for example, that groups like Faust and Neu, through analytic fracturing and stylistic recontextualization, offer a more in depth and intricate way of expanding and adapting conventions of rock music than the drug like meandering of Can. I would also argue that the strategies for dealing with notions of pop are more skilfully deployed by the Love of Life Orchestra's method of simulation than Throbbing Gristle's tactic of alienation. And Glenn Branca more accurately represents the end of the line of contemporary composers than Phillip Glass, who, by virtue of his considerably outdated modes of experimentation, testifies to the lagged perception that steers the course of rock along the road of what it thinks is innovative and progressive.)

Like all manner of social discourse, a particular dominant ideology can be discerned in the hierarchical/hegemonic critical orderings of these groups. Even within the discourse of avant-garde rock, those groups with a stronger attachment to the mythical soul of rock'n'roll (raw energy and social rebellion) are generally more favoured by the rock market than those groups which experiment more with rock forms and contexts.

And our problems do not end there. Moving into the latter half of the 1980s, the inaccuracy of the term avant-garde rock is coupled with its increasing inappropriateness. The post-punk dichotomies which checked and channelled its growth in the late 1970s have now relaxed, reformed, multiplied. The notion of experimentation now figures as a formal set of styles, figures, gestures and conventions, able to be simulated and repeated, leaving new and unattended contexts to redefine the notion: record production, media manipulation, ethnic fusions, stylistic appropriation, multicultural pop, technological innovation, historical quotation, etc.. One can thus now experiment while sounding amazingly conventional.

Just as rock in general has embarked on a quest of rediscovering its multi-layered histories, the categorical awareness of style is so accute one can label any formal experiment as a particular subgenre or polyglot. For this reason, one can no longer simply lump overtly 'non rock' trends into a void of otherness. While transcultural projects continue to spread and mutate across social and commercial spheres, avant-garde rock continues to congeal. Ironically, while the term has been extremely problematic, it is now becoming most effective in economically labelling a historical milieu. (Richard Lowenstein's film Dogs In Space, is a feature dramatisation of the underground rock scene in Melbourne during the late seventies and an example of the historical congealing of a supposedly radical epoch.)

It is quite difficult to locate and specify an Australian context for what is essentially an internationalist trend - this self-inflating/deflating category of avant-garde rock. This is not to say that the Australian exponents are derivative or imitative, or that current trends in mainstream pop or underground rock do not operate in similar internationalist ways, because where genre, or sub-categories of musical style are considered, every example carries its own identity. The problem of differentiating avant-garde rock along nationality lines, lies in the way that this stream of rock music connects with the broad historical references and sources more than with localised social and cultural environments. This means that within the wide spectrum of rock and pop, the arbitrary flows that create various musical styles are subjugated by a controlled concern for a music making that searches for a newness that is more deliberated by the music maker than mediated by his or her immediate surroundings.

Australian avant-garde rock then, starts and finishes with the fact that people born and/or living in Australia make Australian avant-garde rock. But such a sub-category carries no mysterious cultural traits that can differentiate its content and substance from avant-garde rock around the world. It is no wonder that groups from Seattle, Brussells, Cornwall, Vancouver and Canberra can provide remarkably similar work without ever having heard of each other's work, simply by plugging into the same historical sources and references from both the histories of art and rock. As in so many instances, "Australianism" might work as a qualification but not a description.

In a strange way, this does have its positive side, in that whereas the audience for what in Australia is called "underground music" (as featured on most alternative radio stations) would be much larger overseas than here, the audience for avant-garde rock (as segregated by most alternative radio stations as being 'weird', 'confrontational', 'experimental', 'arty', 'elitist', 'wanky', 'esoteric', or 'pretentious) here is comparatively nearer in size to that of its overseas counterpart. The international field is small enough to accommodate a less discriminating approach to the music (from whatever country) by its audience. Australian avant-garde rock as small in size as it is appears to have the mysterious fortune of being seen neither in terms of lack (ie. an inferior Australian-made product), nor as culturally peculiar (ie. boasting of a truly Australian quality) but as an example of what basically amounts to a global direction in rock culture. Perhaps the most underrated success stories of Australian exportation lie in avant-garde rock: from The Birthday Party to SPK, to Jim Foetus to Severed Heads.

There are however, peculiarities not in the way that Australian avant-garde is created, but how it survives in a public domain. Since punk and new wave hit our shores in early 1977 (in waves that first lapped at the rock magazine pages of Ram and Juke and then wiped us out with Pollywaffle and Levi ads on television) many a bastard term had been bandied about. An uncredited writer in The Australian Music Directory lumped together groups like Men At Work, → ↑ →, The Crackerjacks and The Primitive Calculators as all being "New Music"! while Stuart Coupe and Glenn A Baker's book New Music gave a global view of what in essence was just contemporary rock music, but which used the same term which in the context of experimental music signified contemporary excursions into the philosophical notions laid down by John Cage all sounds are music, silence does not exist, the listener is the composer, etc.. Similarly, streams of Australian rock journalism are as likely to include Hunters and Collectors with Laughing Hands in what would appear to be a radical departure in categorization: avant-garde rock. Yet the only thing that could tie the above two groups together would be their non mainstream positions in rock. A major Australian phenomenon (at least contrary to, say, English journalism) would be the precise and direct classification of mainstream or Top 40 acts and the 'mixed bin' approach to anything not in the Top 40. Pale attempts to rectify this don't work too well either, as the classification always works in the negative: 'independent' (not signed by a major label), 'experimental' (not adhering to conventional expectations of form and content), 'alternative' (not part of mainstream activities, pursuits and expectations), or 'underground' (not receiving broad media coverage). As such, all these negative terms do nothing to specify the nature of avant-garde rock, short of taking it out of the 'mixed bin' only to place it in the 'too hard basket', humbly bowing to the historical tradition of not understanding it.

Perhaps an even more major factor in defining the lack of place of avant-garde in Australia would be in the way that it co exists with other musics in that void of Not Top 40. This, of course, is in the pubs. We now live with the legacy of pub rock weighing us down to such an extent that whereas once live music enjoyed a multiple choice situation outside the venues such as Kooyong stadium in Melbourne and the Horden Pavilion in Sydney, we now only have a profusion of bars, hotels and pubs from which to choose. The early 1970s choice between a club, a discotheque, a town hall, a bar, a coffee shop or even a drive in has now become a choice between certain pubs. At the least, these days, these places are thought of in terms of licensing laws and permits for the consumption of alcohol. This all works so much so that "pub" is the neutralised name for a venue. The media coverage of pubs now works to such a standardised format (the ubiquitous Gig Guide) that alternative venues are quite difficult to promote.

The real problem though, lies in the social atmosphere generated by a pub, which in turn creates a localised context in which a site specific music making is produced. Unfortunately this narrows the breadth of musical or other activities that could happen in such a locality. Pubs are no doubt suitable for the rock tradition of a direct as possible relationship with an audience (we even have its namesake subgenre Pub Rock), but they facilitate a very predetermined listening perception. Like a big fat oaf, the pub is able to declare all musics not workable within its environs as stupid, pretentious and boring. The power of the pub most clearly manifests itself in the way that alternative locales that are used cannot be effectively maintained as sites of regular productivity. Few appropriations of sites, venues, or contexts have been successful: SPK's performance at the Sydney brick works, the 'little band's' use of the Champion Hotel, → ↑ →'s insertion into the gallery/museum system. (Varying and unstable degrees of success were also to be found in the Clifton Hill Music Centre, the George Paton Gallery, the Killayoni Club, the Seaview/Crystal Ballrooms, the Mt Erica Hotel, the Prince of Wales Hotel, the Commercial Hotel, the Met Coffee Shop, the Universal Coffee Lounge, the Glasshouse Theatre, and the Union Theatre in Melbourne; Art Unit, I.C.E., the Hip Hop Club, the Performance Space, the Mossman Hotel, Paddington Town Hall/Metro Television, the Gap, the Departure Lounge, the Cell Block, and His Governor's Pleasure in Sydney.) Ultimately, pubs house avant-garde rock under pseudo terrorist terms by 'taking over' a pub for a night. But this approach is no different from having a male stripper every second Tuesday night. Avant-garde rock remains a ghetto in a ghetto: far from Top 40 material and just as far from the cultural channels that have been set up in opposition to the mainstream of rock and pop.

To argue that avant-garde rock remains a ghetto because of its self-professed alienation, because of "what it sounds like", is oversimplifying the case. In Australia, at least, avant-garde rock is contextually snared, positioned by a framework of levels of music production that traffic its consumption and affect the perception of it as a music activity. To translate it as the forefront of contemporary rock music gives a false impression of our rock culture moving along in one glorious channel where everything sits in its allotted place and where eventually, too, avant-garde rock will find its right place, due to the changes in the listening perspectives accorded it. Alas, our ears have to do the least amount of work because if avant-garde rock ever does find a large thriving and continuing audience in Australia, it will not totally be due to our tastes having progressed but primarily because we have been socially and culturally repositioned in a way that faces us in its direction. It might as well happen with baseball as avant-garde rock.

Ultimately, I am fated to flounder with definitions of rock music and avant-garde rock music, no matter what their differences appear to be nor how safely they are able to hold their distance from one another. Strands of reactionary rock music with their "Fuck Art! Let's Dance!" mentality are just as condemnable as strands of avant-garde rock that base their work on a naive and shallow interpretation of the rock music it rejects. Also, avant-garde purists in the academic realm of the contemporary, experimental and new music fields, rarely display the flexivity to accommodate the often sloppy approaches to rock experimentation, while the bulk of avant-garde rock can at times be frustratingly uninteresting and uninspiring. The air of negativity in these views is actually born of frustration with what amounts to narrowness in perception in rock and avant-garde rock which all probably reaffirms the strangely nonexistent form, state and context of avant-garde rock.

I can however resort to telling a story, one that I think illuminates the awkward sense of place that avant-garde rock may have. In 1976 I had an interesting discussion with a music teacher at the school at which I was a final year student. We had been listening to twentieth century avant-garde composers like Stockhausen, Boulez and Webern. Being a bit of a rock head I brought in a pile of Krautrock records from around 1972. It was Kraftwerk's second album (1971) that finally broke him. After three sides of the double album he couldn't hold it in any longer: "Why do they have to have that goddamn pulse going through everything they do?" At the time I could not understand his reaction. Only upon writing this article was I reminded of the incident which I can now see in a different light. That 'pulse' was and is, the dimensional barrier where rock starts and finishes for the serious composer and the arch rock'n'roller alike. It is something that with the most hard edged clarity is alienated from the sphere of avant-garde music proper, and with a startling sense of naturalism and realism is tied to rock culture.

The fact is that such avant-garde rock groups are not disconnected from rock music in general. They are displaced within it, entwined in a contorting general consensus of do's and don'ts in rock conventionalism while attempting to experiment under broader terms of sound and music. Even though all avant-garde rock artists continually disagree with one another, they are unified in their rejection of academicism as a controlling (albeit repressive) factor in experimentation. Self-centred improvisationalism, historical naivety and half-digested concepts run rife in their attitudes, but the work produced is sometimes capable of a freshness, looseness and newness of which few experimental composers have been capable.

Avant-garde rock is not divorced from rock: it embraces rock while it only entertains avant gardism. It is segregated from dominant ideological flows of rock culture, yet it is entrenched in its musical and cultural flows. It is thus probably more appropriate and relevant for books and magazines on rock and pop to be giving space to writers to come to terms with avant-garde rock than it is for conservatoria to open their doors and ears to Australian avant-garde. The latter is, I feel, fantasy. But the former is a hopeful possibility.

Text © Philip Brophy 1987. Images © Respective copyright holders