Arashi ga oka

Arashi ga oka

The Sound of the World Turned Inside Out

Published in Japanese Horror Cinema, Edinburugh University Press, Edinburugh, 2005Speaking Japanese and sounding Gothic

The Gothic is attracted to decay like maggots to a corpse. And like flies carrying airborne disease, the Gothic vaporises. It floats along the global trade winds that breathe death through the fetid national identities which distinguish each country's cinema. The Gothic may be Germanic in its morphological origination; it might be English in its formulation of a literary obesity; it might be American in its slippage toward social decline. Its constancy is its suffixing to any cultural identity as a means of decaying that which it touches.

Japanese Gothic' is a symptom of this affectation. The mutative outgrowth of European tropes, figures and icons from noticeably Japanese environs, architecture and landscape is a clear demonstration of how the Gothic performs more as worm wood and less as a rhizome. It atrophies from within to create new chimeraesque shapes rather than sprouting forth additional structures. While European and Occidental Gothic expressions are the result of importation, the Gothic in Japanese guise is the result of direct injection and a consequent inability to digest. The spectre of Japan's unnerving isolationism governs Japanese aesthetics to such an extent that transcultural occurrences such as the Gothic are never subsumed, fused or blended: they curdle, pock and mar their reflecting surfaces into micro-terrains of cultural mutation. [1]

Yoshida Kiju's Arashi ga oka (1988, also known as Onimaru) announces itself as a contorted duality of Gothic imposition, with opening credits declaring its basis as Emily Bront''s Wuthering Heights, and then cutting to an obayashi - the traditional narrational figure in Japanese ghost stories from the medieval period. As she tells the tale of Onimaru to a blind monk, her archetypically rasping voice sucks in the Gothic and expels it through a uniquely Japanese dialect. The Occidental vanishes; the Oriental materialises. The Japanese voice that speaks this versioning of Bront''s novel serves as a sign of its generative Gothic apparition - to such an extent that evoice' becomes both metaphor and metonym in the play between sound and image that characterises Arashi ga oka as a complex audiovisual text. No mere transposition, interpretation or translation of Bront''s tale of displaced souls, windstrewn romance and diminishing vitality, Arashi ga oka eschews all recourse to estaging' its para-Gothic literary origins. In place of nominal literary and theatrical strategies employed in cinematic novelizations, Arashi ga oka orchestrates and arranges the thematic levels of Bront''s tale via Takemitsu Toru's musical score.

Collapsing the orchestra into sound

The first point to make about the score to Arashi ga oka is an obvious one: it is performed by an orchestra. This central detail might fall on deaf Western ears who are happy with efilm music' as unending echoic strains of Wagnerian clich?s and gross operatic gestures. But the point is arch: to employ a European orchestra for a Japanese film is a high-relief effect comparable to scoring Schindler's List with koto. Takemitsu amplifies the musicological schisms that arise from his adoption of the orchestra by employing Japanese technique in the performance and esounding' of the orchestral elements. Largely bypassing the linguistic strictures of Western harmony which tend to apply a default setting to the harmonic building blocks in orchestral writing and performance, instrumental identity in Arashi ga oka is always blurred, diffused, aerated. Flutes behave like whistling kettles; timpani like rolling boulders; horns like tuned wood resonance. No instrument in Arashi ga oka's score presents itself as recognisable. True to the film's ingestion of the Gothic, Takemitsu's orchestration is the result of the orchestra being transformed from within, at the level of tactile performance. No mere vaudevillian mimicry and spookery blasted from the pit below the screen, the score conjures a spectral being living and breathing upon the stage, spot-lit with make-up melting in the lights.

The tactile timbres and seeping sensory nature of the score is always at the fore, accenting the physicality of the orchestral apparatus. In the conjoined history of Western musical progression, the shift from the musical to the sonic is perceived as either an unwanted aberration, a sign of ineptness, or an act of wilful destruction. The evacuation of controlled musical expression and its collapse into tonal impurity, sonic irritation and harmonic degeneration have long formed critical paradigms which qualify emusic' as a grand and noble pursuit. But to an western ear not exposed to Japanese music, the highly skilled performance of a lute (biwa), flute (shakauhachi) or guitar (shimasen) might sound identical to a three year old western child tearing apart a violin. Arashi ga oka features superb solo performances of all these instruments atop the aforementioned orchestral arrangements. Boldly laid across the splayed fields of European instrumentation that squirm like carpets of maggots on moist earth, these uniquely Japanese signifiers of musicianship and performance are emblematic of the evoice' which esounds' the score, and serve to continually remind the ear that they mix with a lush European string section like oil with water. [2]

But Arashi ga oka is a film, not a concert. The score then is affected by and in turn modulates the dramaturgy of the film. And it is precisely here that the power of Arashi ga oka as a Japanese Gothic scenario is discerned. A reading of how the music relates to (a) the interior spatial design and depiction of exterior locations; (b) the psychological development (or deterioration) of the enmeshed characters; and (c) the shimmering and wavering dissolution between sonic atmospheres and temperate musicality, uncovers the musicological map upon which Arashi ga oka is audiovisually staged. Despite the bloody chambara explosiveness and the bodily corruption which posit Arashi ga oka as a dimensional shift beyond the original Wuthering Heights (directed by William Wyler in 1939), the dissolution of the score - its creeping, weeping palpability - is the prime signifier of the Gothic germ that has overtaken this highly mannered Japanese film.

Mapping the terrain of Arashi ga oka

Bronte's Wuthering Heights is as much neglected as it is referenced by Arashi ga oka. This 16th century feudal story details the slow descent into madness of the brutish Onimaru (Matsuda Yusaku) - an unwanted heir to the Yamabe family fortune after the death of Lord Takamaru Yamabe (Mikuni Rentaro) to whom Onimaru has been utterly loyal. Central cause of Onimaru's madness is his frayed bonding to Kinu Yamabe (Tanaka Yuko) after she gives herself over to him after her father Takamaru has been killed by passing soldiers. She does so prior to leaving to marry her cousin Lord Mitsuhiko. Both families belong to the Serpent Clan who live on the Sacred Mountain, each owning a huge mansion on opposite sides, and each wholly opposed to the other due to generations of feuding. Forced to become a Shinto priestess at the capital once she reaches womanhood, Kinu marries Mitsuhiko only so that she is allowed to stay on the mountain and hence near Onimaru, even though her marriage to Mitsuhiko prevents her from seeing Onimaru again. Onimaru is angered by her marriage and leaves to return some years later from the capital as a Lord to whom is bequeathed dominion of the whole mountain - including the household of Kinu and Mitsuhiko. Kinu has had a daughter, Shino - likely to be from her past sole union with Onimaru.

Kinu dies; Mitsuhiko is slain by robbers who in turn are butchered by Onimaru. Deeply disturbed by the death of Kinu, Onimaru disinters her body from the mountain's Valley of the Dead, risking supreme damnation. A now-adult Shino (Ito Keiko) travels to Onimaru's mansion full of hatred toward Onimaru as she believes he killed her father. Shino is intent on retrieving her mother's coffin and remains, and plans to drive Onimaru mad by reminding him of her mother. After finding then hiding her mother's remains from Onimaru, Shino's attempt to seduce Onimaru backfires when he reveals his past affair with her mother. Onimaru reclaims Kinu's coffin and withdraws into deepening neuroses and visions. Aged and lost in his insane bond to the skeletal remains of Kinu, he has his right arm severed in a conflict with Shino's young cousin, Yoshimaru (Furuoya Masato). Presumed dead, the one-armed Onimaru miraculously reappears as Shino and Yoshimaru return Kinu's coffin to the Valley of the Dead. Onimaru regains Kinu's coffin and drags it into the rising mist covering the upper reaches of the Sacred Mountain. [3]

The settings for Arashi ga oka are essentially polarised between the chiaroscuro interiors of the east/west mansions, and the unforgiving volcanic landscape of the Sacred Mountain (also referred to as a 'fire mountain'). The figures of Onimaru, Kinu, et al are positioned within these settings as delicate gestural shapes, mostly layered in relief against massive and expansive backdrops of colour and texture. They are materialisations of the solo traditional instruments (biwa, shimasen, shakauhachi, koto, taiko, etc.) dancing atop the seething density of the orchestral murmuring which represents the haunting terrain of the Scared Mountain and the penumbral gloom of the east/west mansions. While visual grandeur and eopulent minimalism' is readily apparent, Arashi ga oka's overall brooding tone arises from the way the sound design and film score interpolate these settings. Predominantly, when we are outside on the dark ashen mountain, the orchestra sounds like howling wind; when we are inside the cavernous mansions' rooms, we hear actual moaning wind. This is a major reversal of the dominant logic of western mimetic cinema (labelled 'realism', 'naturalism', etc.) in that music is often deemed the voice of humanist enterprise and dramatic conflict, while landscapes are enon-human' and thus often felt to require non-musical (i.e. sonic) representation. Arashi ga oka consistently places sound as the backdrop to the chamber dramas in the mansions, while music is employed to speak the voice of the landscape. This conceptual technique is typical of much Japanese cinema wherein land is inextricably linked to the psyche and spiritual tenets place the human and the non-human on a coexistent plane of energy.

Yet Arashi ga oka invigorates this Japanese cinematic template of audiovisual construction. Through Takemitsu's quasi-spectral compositional approach, the volcanic carpet of the Sacred Mountain becomes a mindscape for the characters as they are emptied of all social mores in their decline to madness; the composed silence of the mansions' rooms is amplified to form hollowed resonators for the characters' emptiness. Opposite to western notions of house design, the traditional Japanese domus is to welcome sound rather than block it: paper walls allow sound to filter through; wooden floorboards create reverberant points of contact for sliding doors and walking feet; the sounds of nature outside flow throughout the house as a soundtrack to framed openings onto manicured gardens. The Japanese experience of what constitutes the relationship between inside and outside of both home and environment is substantially different to those of us living in bricked and plastered walls and closed glass windows. Consequently, the symbolic role of interior and exterior sounds performs differently - especially in the film's imposition of the Gothic whose symbolic codes accent the repression of the inside and sensationalise its unleashed rupture of the outside.

Arousing the interior and planing the exterior

Arashi ga oka sounds this difference of the interior/exterior bind at two levels. Firstly, the score charts the shift between objective capture of scenes and subjective impressions of being in those scenes. Soft timpani rolls fused with richly bowed double-bass against a panorama of the Sacred Mountain will simulate wind but invoke the power its mass has on the minds of those who traverse its barren terrain. At other times, bass-heavy droning wind against the same panorama will simulate a portamento pitch drop of a bowed double-bass but evoke the acoustic characteristics of wind travelling low to the ground to create an ominous hum typically felt on such terrain. The edifference' between these two aural states concurs at the symbolic level, but their actualisation - their choice of aural rendering - reflects the angle at which the drama is positioned as it moves forward. In effect, this is emusic as mis-en-scene': a staging of sound that becomes a plane upon which theatrics are played out.

The second way in which the interior/exterior bind is articulated as different to conventional western modes of audiovisuality lies in the narrational aspects of the music. The score employs its solo instrumentation of traditional Japanese instruments to embody the psychological stature of its characters. For example, Onimaru is esonically signed' by growling low frequencies (drums, cellos, oboes) and a low shakauhachi; Kinu by a blend of koto and harp, and a high shakauhachi. Now while this might seem standard practice in western cinema (thematic representation of characters through instrumentation), Arashi ga oka displaces these themes into a complex bio-rhythm that at time synchronises with on-screen depiction of a character and at other times completely dislocates any continuity or simultaneity. Over a static shot of Onimaru might be the shakuhachi line of Kinu, but then allowed to carry over into a landscape shot of the mountain. Contained within this complex interweaving of themes and their roving, shifting apparition is the way in which sound effects, atmospheres and foley will appear and disappear according to intensity or prominence of the psychological fissure being presented at any one moment. The mix of the film is thus a psychologically monitored one and accords little to the linguistic/structural guidelines of realist/naturalist cinema. This is emusic as dramaturgy': an arousal of the interiority of the story's characters expressed beyond and despite the plastics of the filmic construction (costume, sets, lights, camera, etc.).

Some detailed charting of the ways in which Arashi ga oka's score articulates its weave of sonarised mis-en-scene and dramaturgy can now be undertaken. The terrain of Arashi ga oka is the breadth and depth of the Sacred Mountain. A volatile geography, its volcanic aspects figure it as unsettled earth whose ground is unfixed and whose fluctuating temperature suggest its living quality. Following folkloric tradition, the Lord of the Yamabe family must annually perform the Rite of the Serpent, designed to keep the serpent deep within the earth. Its symbolic rupture of the earth is deemed responsible for crop failure by the villagers, hence the need to repress its arousal. Yet the sexual symbolism of the rising serpent is the sediment to Arashi ga oka's unending sexual tension. Read this way, the low rumbles which flow throughout the film like a sonar network of invisible ducting symbolise the earth as a living corpus which affects and controls those who touch its surface. From the occasional subsonic vibrations which shudder the mountain's slopes of dark gravel to the low-toned wind drafts surging throughout the wooden corridors of the mansions, the earth is a responsive being triggering states of arousal in its denizens.

While such a view of the earth would be aligned to mystical and fantastical tropes in western story-telling, Japanese culture supports the animist notion of spiritual energy contained within the apparently einanimate'. The earth and all its discontents are as alive as any human. When Kinu and Mitsuhiko discuss the bond each of their clan shares with the mountain and its serpent essence, low-pitched oboes and clarinets swirl around each other in snaking lines to musically represent and symbolically evidence their awareness of the mysterious power embodied by the mountain. Notably, the volume level of this theme almost overcomes the dialogue track, indicating how elemental energies can overpower the human.

Becoming the Other and visceral rendering

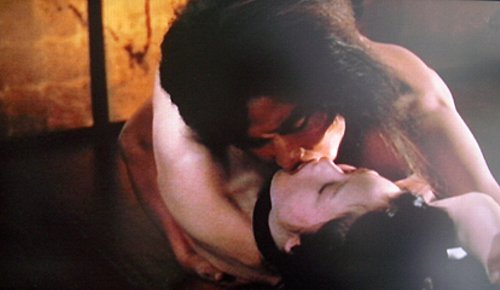

The core of Arashi ga oka's drama is sited in the elove action' between Onimaru and Kinu. This actioning of desire, consummation and obsession is concentrated in their lovemaking scenes. Prior to their first physical encounter, each bathes in seclusion. A naked Onimaru roughly buckets water over himself, the bursts of white noise gashing the silence of the mansion. Earlier, clothed in white muslim, Kinu has had cupfuls of water carefully poured down her lithe form by her attendant. The water barely makes a trickling noise; in place is a series of delicately plucked koto notes and tinkling chimes. This musical tinkling represents the upper filature that breaks free from the corporeality of the earth: Kinu is hovering on the transcendental cusp of becoming eother' than the Shinto priestess custom dictates her to be.

These tinkles also represent an inner nucleus to the swirling sexual energy which both polarises and attracts Onimaru and Kinu to each other. After they have made love, Kinu is attended to by her maid while holding a mirror. She is transfixed by her own image (like she was as a child when first given the mirror by her father) yet narcissism and vanity have no play here. As her oval face hovers like a beautiful orb within the circular frame, Kinu chants softly to her reflection, "He is here. I am Onimaru. Onimaru is me." Not only has his seed taken hold in her body (symbolised by the mirror as womb), but she has given herself over to him as an act of self-erasure. When she departs to start a new life with Mitsuhiko, she is, as she says, Onimaru. The tinkling thus actions the presence of Onimaru in shots or sequences where he appears to be absent.

The lovemaking of Kinu and Onimaru takes place in a glowing room tainted with what suggests smears of dried blood. This rosewood-toned colourisation of the room's screens is never outrightly explained (Onimaru enters and declares, "It's the smell of blood, not damp mould") though when Kinu first encounters the space she clearly finds its aura unsettling. This humoral room is actually referred to as the Seclusion Room where household members are interred as acts of punishment. Kinu acknowledges her wrong in seducing Onimaru by performing their sexual union in this Seclusion Room. When they have sex, a seductive edance' is first deployed, as each hovers around the contours of the other's body, suggestively following its lines with finger, hand, tongue, hair. They contort and entwine like two snakes, engorged by the energy of the serpent spirit of the mountain. Tuned wind drafts rise and fall in response to the intensity of their movements. Swirling around them like sonic smoke curls are two shakauhachi solos, a low flute and a high flute engaged in a sensual dialogue. Having conjured forth the serpent energy into the realm of the corporeal, the music represents this transformation of their selves by functioning as a form of oxidised sexuality: airborne, it molecularly transforms their space. These floating flutes are thus not symbolic of Onimaru and Kinu per se, but moreso the transformation they underwent. As they move into tactile embrace, all foley sound effects disappear: they have absented themselves from the plane of physical existence to become the Other.

Apart from trailing across the end credits roll, the only time the dual shakauhachi theme appears in full-bodied form is during the above lovemaking scene. Elsewhere, the flute solos are sounded alone. When Kinu dies, she is seen through a muslim gauze similar to the fabric she wore during her ritual bath before being with Onimaru. Fevered and dying slowly from within ever since she left Onimaru, she now claims to hear the sound of Onimaru's horse's hooves. The deep timpani rolls we have heard many times now come to the fore: this is the spirit of the mountain sounded through the spectre of Onimaru who has been possessed by the spirit of Kinu who seduced him as she in turn was controlled by the mountain's sexual energy. The looping here is important, remembering not only how Kinu perceives herself as one with Onimaru, but how the low rumbles symbolise the way the mountain affects those who walk upon it. Crying that she'll drag Onimaru down to hell, her last words are spoken calmly: eOnimaru, you are dead'. Throughout this scene, Onimaru's low shakauhachi plays the exact solo dance it performed during their love making. Read through visuals alone, the scene would be one of desperate revenge. Acknowledging the transferrals that have occurred between Onimaru and Kinu, plus the presence of his sexual ebecoming' flute theme, the scene is actually a morbid sex scene - one that forecasts his descent into necrophilia.

Possessed by the spirit of Kinu - and equally dispossessed by not having her body following their sole night of love - Onimaru is driven to extend his consummation of her being after death. When he first opens her coffin, Kinu's decaying corpse is illuminated by lightning and revealed as an undulating spread of maggots. Mixed atop the sheets of lightning noise and deep thunder claps (prime sonic signifiers of rupture and transgression in global Gothic cinema) is Kinu's high shakauhachi theme played solo. This is Kinu dragging Onimaru down to hell by sexually luring him to take her despite her state of decrepitude. Onimaru passes over to the other side in his love actioning here as he embraces both what he has become and what the mountain has made of the bond between him and Kinu. The breathiness of their shared shakauhachi sighs are as hot and moist as breath felt on your own neck, imbuing their musicality with a viscerality that allows the film to waver between erotic denouement and pornographic stimulation.

From this point on, Onimaru lives in his own eValley of the Dead'. Two notable scenes extol this in unsettling ways. The first is when he throws Mitsuhiko's sister, Tae (Ishida Eri) into the Seclusion Room after she travels to the east mansion in order to become Onimaru's bride. Sensing the spite which impels her desperation, he rejects her sexual advances which she uses as a means to overcome and control him. A terse gender confrontation occurs, as she flaunts herself as a reappearance of the dead Kinu, not realising that he could only relate to her as the dead Kinu. Psychologically sparring with each other, he is overwhelmed and rapes her as a vessel of enot-being' Kinu, dry-humping the absence of Kinu embodied by the physical form of Tae. Tae's face expresses outrage not simply at being raped, but revulsion at ebecoming symbolically dead' in the grasp of Onimaru. The depths of his madness shock her so much she hangs herself at the gate of the east mansion the next morning. Throughout the rape scene, the shakauhachi lines affirm the presence and absence of Kinu as a dark shadow cast upon everyone.

The seemingly blood-stained walls of the Seclusion Room are less material residue and more a sexual ectoplasm that defines an epidermis to this erotic realm. The second scene that depicts the morbid domus of Onimaru's mind occurs when Shino cloisters herself in the room - first lying in Kinu's coffin, later appearing naked and ready for sex. She taunts Onimaru by flaunting her body; wind drafts sonically surge around the room and cause a candle Onimaru holds to lap and dance around her body like he once did with Kinu. As he eyes the genetic imprint of Kinu upon her daughter's form, Shino dares him, "Come - hate me if you can." This time Shino is a corporeal manifestation of Kinu's shakauhachi solo: Shino carries on the love-actioning of Kinu as an act of becoming that which haunts and lures the crazed Onimaru.

'Turned inside out' and sono-musical conflation

The graveyard of the Yamabe clan on the Sacred Mountain - poetically named The Valley of the Dead - is often accompanied by swirling and slow-throbbing oboes and clarinets. A possibly straightforward choice of instrumentation, but the accent of woodwinds relates closely to the terrain being one of degraded wooden coffins. It is almost as if the wooden coffins have been remodelled into woodwinds in order to sound human breath through their morbid materiality. This is no over-reactive reading of the use of woodwinds, as elsewhere in the film wind is the breath of the mountain, rumbling across the mountain's dales and troughs and tunnelling down the mansions' corridors. Takemitsu's approach to scoring is often based on an animist awareness of the materiality of chosen instruments, and clearly in Arashi ga oka wood, wind and death are thematically and aurally fused.

Essentially, Takemitsu is less engaged in efilm scoring' as we know it and more absorbed in edecomposing' music for the film's Gothic-infected scenario. Rather than presume the cinematographic scenario is somehow a ephoto-realist' document of drama which requires the non-diegetic mode of musical discourse to articulate a human perceptiveness (the lofty yet limited quest of most classical western film scoring), Takemitsu's approach is to emake sound' from the abject materiality of the components which exist within the diegesis of the depicted world on screen. In doing so, he effectively turns the cinematic world inside out, hiding the thematic striations which obviously suggests dramaturgy to the film composer, and revealing the sonic elemental nature of a film's fabric. This perception of the world is a key philosophical determinant in the sono-musical conflation strongly associated with Takemitsu.

Yet Takemitsu is not an imposition on Arashi ga oka's dramatic logic or fictional realm. His method of edecomposition' is perfectly suited to the film's Gothic impulse as well as its visceral rendering of suppressed thematics. Recalling the aforementioned eaeration of musical themes', one must acknowledge its resonance with the central notion of decay which drives the Gothic in general and Arashi ga oka in particular. When the inside of the body is exposed through incision or rot, airborne germs gain access to that which hair and skin block and cover, causing decay of the most mortal kind. Onimaru experiences this potently when he disinters Kinu's body, but as also noted, he is affected by the psychic stench unleashed by Kinu's bodily decomposition. Inner and outer realms - their trembling disclosure, their acidic meld - are also at the base of the story's social construction. Takamaru holds an awesome power over the villagers by enacting the Serpent Rite to keep the mountain's serpent energy at bay and assuring their livelihood.

However he is acutely cogniscent of the theatrical charade he enacts, declaring, "Now is an age of wars. Only fools worry about curses or divine punishment." Yet true to the Gothic drive to prove that which one most denies or refuses to believe, he neglects how the mountain's ominous form has affected the sexual and psychological composure of the family he has built on its bed of volcanic rock. Desire, love and familial growth are thus affected at the micro-level, allowing for a fulsome decay and deterioration to take hold of everyone.

The Gothic - encompassing its criss-crossing folds of eNeo-Gothic' which historically skirt both the sub-history of serialised romances and the validated examples of great 19th century novels - returns uncontrollably to the sensational intersection of the morbid with the romantic. Never tragic but always titillating, the Gothic loves death and loves to count the ways. Its thrill within western modes is one of knowing the silent, hearing the mute, acknowledging the unspoken. Gothic literature's excessive descriptiveness (precursor to cinema that edwells on the unsavoury') is an erotic striptease of signification, where the unutterable is framed and spot-lit but never named or spoken. A complex of Judeo-Christian mores and Eurocentric morals might block the Gothic from rendering the totality of its unspeakable action, but Japanese Gothic has neither qualms nor concerns in adhering to the caveats placed on the Gothic's lean to the lurid. Hence, the wuthering musical depths and psycho-sexual heights of Arashi ga oka that truly is the world turned inside-out.

Thanks to Chiaki Ajioka and Rosemary Dean.

Notes

1. Not a particularly official genre of horror, 'Japanese Gothic' would be ably demonstrated by notable films like Nakagawa Nobuo's Kyuketsuki ga (1956), Kaidan kasanegafuchi (1957), Borei kaibyo yashiki (1958) & Takaido yatsuya Kaidan (1959); Shindo Kaneto's Onibaba & Kobayashi Masaki's Kaidan (both 1964); Kobayashi Tsuneo's Kaidan katame no otoko & Sato Hajime's Kaidan semushi otoko (both 1965); Shindo Kaneto's Kuroneko, Yasuda Kimiyoshi's Yokai hyaku monogatari, Kuroda Yoshiyuki's Yokai daisenso, Yamamoto Satsuo's Kaidan botandoro, Tanaka Tokuzo's Kaidan yukigoro & Hase Kazuo's Kaidan zankoku monogatari (all 1968).

2. For more on Takemitsu Toru's approach to film-scoring especially in relation to horror, see Brophy, P. (2000), How Sound Floats On Land: The Suppression & Release of Indigenous Musics on the Cinematic Terrain, in P. Brophy (ed.), Cinesonic: Cinema & the Sound of Music, Sydney, Australian Film TV & Radio School, pp. 191-215.

3. For an analysis of the depiction of Woman in Arashi ga oka, see Iwamura (Dean), R. (1994), Letter from Japan: From Girls Who Dress Up Like Boys to trussed-Up Porn Stars - Some Contemporary Heroines on the Japanese Screen', Continuum: The Australian Journal of Media & Culture, 7: 2, 109-130.

Credits for Arashi ga oka

Onimaru - Matsuda Yusaku

Kinu - Tanaka Yuko

Mitsuhiko - Nadaka Tatsuro

Tae - Ishida Eri

Kinu as a girl - Takabe Tomoko

Yoshimaru - Furuoya Masato

Takamaru - Mikuni Rentaro

Hidemaru - Hagiwara Nagare

Shino - Ito Keiko

Sato - Sugiyama Tokuko

Ichi - Imafuku Masao

Suke - Ueda Shun

Director - Yoshida Kiju (Yoshihige)

Producers - Yamaguchi Kaz Francis Von Buren

Writer - Yoshida Kiju

Cinematographer - Hayashi Junichiro

Set - designer Muraki Yoshiro

Composer - Takemitsu Toru

Sound design - Kubota Yukio

Editor - Shirae Takao

Text © Philip Brophy 2005. Images © Seiyu Production & Toho Company