Body Melt: Philip Brophy

Transcription of interview on The Screen Show, ABC Radio National, Thursday 25th April 2024Interview by Jason Di Rosso

Body Melt is an Australian classic. It has fans across the world – some high profile ones including Quentin Tarantino as well. And I’m reliably informed that Nick Pinkerton is also partial to it. It came out in 1993. It’s a splatter satire set in the suburbs, about a malign fitness corporation peddling a vitamin product that has unexpectedly catastrophic side-effects on the human body. And it depicts the panic that sets in, as residents from Pebbles Courts in the outer Melbourne suburb of Homesville fall foul of the product, and find their bodies melting, exploding and generally malfunctioning in a myriad of gooey, sticky, liquidy ways. Into the mix, there’s also an evil scientist, there’s the veteran detective scratching his head as some of the weirdest corpses he’s ever seen pass through the police morgue, and a family of deformed inbred country hicks. Director and co-writer Philip Brophy is one of Australia’s best critics and film scholars, and a respected sound artist, and Body Melt is his only feature film to date. But, it has never been forgotten.

JDR: Philip Brophy – welcome to the Screen Show.

PB: Thanks for having me, Jason.

JDR: I’m really curious. I don’t know how you got the money to make this film, and so I wanted to begin with that. Let’s begin at the beginning, because it is such a singular kind of film to come out in the early to mid-90s. How did you get the support to make it?

PB: I think all films get made basically by luck, and the luck comes from someone wishing and willing to gamble on you. And that’s all it is at the end of the day. It doesn’t matter how much producers or studios or anyone says there’s all these reasons why they are investing into something. It’s all just playing at Crown Casino or somewhere in Vegas – whatever. The best people that are involved in filmmaking at that end of things are the ones that absolutely accept that it’s completely risky, and don’t attempt to rationalize things. And that’s exactly what happened with Body Melt. It was funded by what was then the Australian Film Commission (before Screen Australia) and at that point there was a British guy – what I call a Pom – a great guy, Peter Sainsbury, that was the head of the AFC at that stage. And he literally took a gamble. And I do remember being there with the co-producer Rod Bishop (who also co-wrote the script) in a meeting with Peter Sainsbury, and it really just came down to that. We had debated it with so many different people along the lines of back then – in the early 90s – why an Australian government body should be interested in supporting something that potentially was a form of exploitation cinema – a genre film. These days, everyone and their dog and their mother and their grand-uncle think that they’re being kind of hip by making some sort of ‘intelligent' horror film. They’re all awful. But now the genre – and various genres, in fact – have become more respectable. Back then, I was basically, you know, advocating child pornography by wanting to make a kind of splatter style horror movie.

JDR: It was seen as beyond the pale, that kind of filmmaking, was it?

PB: Look, I can understand why, and frankly, I probably overdid it, in being a bit too cavalier in presenting myself as someone that was, you know, there to basically say “It’s not my task to say why you should make this film - it’s actually your task to say why you shouldn’t be making the film.” And that’s kind of arrogant and sparky and what not, but it won through because the person at the other end evaluating that argument was willing to take a gamble.

JDR: I just want to point this out for listeners who don’t maybe know, everyone I know who was in the industry at around that time in the early to mid 90s speak so highly of Sainsbury. Just the other night I did a Q&A with Margot Nash – a radical feminist filmmaker who came up through the 70s and did radical work – very in-your-face work like Body Melt is – and she also spoke very highly of Sainsbury in getting her first feature across the line. But there are others as well. I think you described what he had and what he brought to the Australian industry very eloquently. I mean, he just had a vision. Was he a cultured man?

PB: Oh yes, he definitely was cultured, but also he knew that culture can be enlivened by political stakes being played with, rather than being adhered to. So he was interested in flexibility, and interested in broadening things, and interested in a kind of pluralism, in that a film culture in Australia needn’t be jingoistic Banjo Patterson bullshit, which was the kind of movies that essentially Australia was making at the time – and is still making to this day, this idea that there’s somehow something fantastic in our colonial past. The only thing that’s good in out colonial past is how mucked-up it is, and if you’re going to address it, then just show it in the most nihilistic, decrepit way possible. Don’t try to make a celebration of how ‘great’ it is! It’s hard to remember now what it was like in the 90s and the 80s, but to me, all Australian cinema was disgusting. It was like all one big Man From Snowy River. And I’m a young kid at that stage, and I’m like “who in their right mind would go and see a movie like that?” I just had different interests. And so from the idea of having different interests as a director to then pursue them and eventually make a film: that can only happen in a broader, pluralistic film culture.

JDR: I did want to ask though, did you see yourself as in any way aligned with or sort of descendent from some of the cinema that had come up in the 70s and the 80s that was a little bit outré or outrageous? Everything from the Barry McKenzie films to maybe something like Turkey Shoot? Did you see yourself at all that way?

PB: No! Not at all. I can see that laterally there is a kind of national cultural continuity. That type of continuity – it doesn’t matter what you think personally, you will get caught up that momentum. But to me – first off: those films that you’re talking about, as someone that was involved in Punk at the time, they were just old fart stuff. It was like celebrating Vegemite! Plus even at the time, in a fairly naive but kind of clear way, I despised any form of mocking of working class culture by middle class, university-trained satirists. To me that’s still what we live with in Australia – this idea that you send up bogans in some kind of wry way. It’s like, please: why don’t we just send up wannabe lame comedians working on the ABC that were once lawyers at university. I mean, that would be funny.

JDR: That would be quite outrageous. That would be legitimately irreverent, I believe! I want to talk to you about the casting of this film before we go on to talk about the gore and the splatter, which I think is fabulous in this film. Gerard Kennedy at the time was synonymous with TV, the cop shows in Australia – especially Division 4. I see him referenced around Homicide all the time, but I remember him as one of the Division 4 guys. How conscious were you of dragging this kind of figure of the esteemed televisual tradition of Australian policiers, how conscious were you of dragging this symbolic man into your hysterical bad taste circus? How much of a deliberate provocation was it? He’s wonderful in it – he’s such a good actor.

PB: Yeah, he’s fantastic. I have to say it wasn’t deliberate or conscious. It’s the result of very early on in all my work back then since: the idea of making a movie that somehow looks and breathes ‘cinema’, that somehow is quintessentially ‘cinematic’ to me is utterly repulsive. It’s so lame and desperate and wannabe. Like, “One day I’m going to make a movie, and I’m going to have a really long tracking shot, and there’s going to be hoards of people, and we’re going to be up in the crane, and the sun’s setting, and there’s a beautiful child in silhouette, the wheat fields –" everyone of these 2-bit clichés that are from the great history of amazing European cinematography, or are just copies of scenes from Tarkovsky films- to me, that idea of cinematic aestheticism is the realm of hack advertisers and really tacky video clips. This kind of desperate plea to say: “I’m quality!” And that they’re somehow better. To me, what Australia is in terms of its visuality, in terms of what it actually produces as visual culture, it’s essentially a televisual culture. It’s not a cinematic culture. Other nations really have a really strong cinematic visuality. We have televisuality. It’s much lower grade, and it’s not as sumptuous, and it’s got embedded in it a kind of mix of lower-middle class to working class artefacts, that seep and breathe through it all the time. So when I was coming up with Body Melt and I wanted it to be not just in the inner city, not even in the suburbs, but in the outer suburbs. It had to be so far away. I’m thinking in that world, what it is in terms of its visual veneer, it really is just like looking at shows at the time like Healthy Wealthy Wise. Banal homes. Banal driveways. Banal cars. None of it really tacky, but a little bit kind of quality. And so that look, that essence of what advertising and television looks like on Australian TV, that’s visually what I wanted.

JDR: So Gerard Kennedy is part of that televisual culture, I suppose. Can I just name them: Lisa McCune, Andrew Daddo, Brett Climo, and of course Harold from Neighbours, Ian Smith, who’s this wonderful villain in your film. And I loved the way – I want to ask you about how directed him in a moment, because I love the way that his is a very sincere kind of performance, but it’s not like a comedian hamming up seriousness. It’s a classic serious villain. He’s very good, and it counterpoints beautifully with the over-the-top gore that you have in the film.

PB: I have no time for any form of cinema or television that’s winking to the audience, that’s kind of letting them know that “We’re in on the joke, aren’t we?” Like, “Here I am dressed as an awful salesman somewhere, but really I’m not: I’m such a hip dad!” I can’t stand that form of comedy.

JDR: I think unfortunately that Kath & Kim went over that line. I think there are some good things in Kath & Kim - you may disagree - but that goes over that line sometimes, where you think these are actors pretending.

PB: But fair enough – that’s what they do, and there’s a lot of people that like that broad kind of comedy. To me it’s a very British form of comedy. It’s almost like a form of Thatcher-era anti-pantomime, this idea of broadly sending-up something for political critique, and kind of letting the audience in on it. It’s self-congratulatory in some sense. I was interested only in making something that was indistinguishable from the crap that’s on TV. I’ve often described Body Melt as: to come up with the idea, all I did was watch television and ads on television, and I would just literally fantasize in my head “OK – now I want them to crash in car, and a dog to come and urinate on them”. That would have been an ad for some insurance company, and I would fantasize in my mind this melt-down scenario. And really, it was easy to come up with those ideas, in terms of putting them together in the film. So it’s got a kind of small apocalyptic edge to it, but the reason for wanting that kind of apocalypse is just because I find that particular televisuality oppressive and limiting. I think were still living with it today, with every 2-bit celebrity chef. It doesn’t matter whether it’s ABC, SBS or any of the commercial networks. It’s the same kind of fodder that’s ‘informing’ you, getting you excited, and you’re ‘learning something’, and there’s a moral consideration – please. I find it draining. So Body Melt is really about that.

But to answer more specifically your question about the acting, with my previous work like Salt Saliva Sperm & Sweat I was I guess in a traditional experimental mode, where you’re not looking for any form of naturalism. You’re not looking for those more complex crafting that the actor of course can deliver for a film. And plus, I wasn’t experienced enough to do it. I’m aghast in the way that so many first-time directors feel they can jump in to tell actors what to do. From my perspective, when I look at it, a director in one year probably spends about 1% - if they’re lucky – actually directing a movie. Whereas an actor, they’ve been doing gig jobs the whole year – at least 50%. So actors are supremely more experienced than directors, without doubt. Not that I was intimidated by it, but I was almost thinking: “Really, actors know what they’re doing”. I’ve always said that with Australian film, if the director did not show up, every other department working on that film, from the producer down to the set decorators to the hair and make-up, to the actors themselves, would be able to get the film done. The cinematographer would take care of all the lighting. And then whatever happens at the end of the day, the editor would then be able to fix up any problems. I really doubt the power of directors. So when I was working with these actors, it was basically a matter of talking with them in a pre-production way, and saying to them “This isn’t a Melbourne University comedy revue send-up of the outer suburbs”. This is a horror story. There’s no ghost or goblins or monsters, and it’s not really even ‘horrible’. It’s just icky. It’s just like the shit hitting the fan kind of stuff. All you’ve got to do is be that kind of person, as if it’s a TV show, where you’re the detective, you’re the sidekick, you’re the doctor – whatever. Play it for what it is. Don’t do any winking to the audience. Don’t exaggerate. And every single one of the actors completely got that. I had spent the previous four years explaining to every 2-bit politically informed person involved in the investment chain what the film actually was. Hardly any of them got it until Peter Sainsbury said “I’m going to go with it”. Whereas the actors instantly got it.

JDR: I think one of the things that’s great about the film is its comedy, and I’m not one to necessarily love sort of splatter comedy, so for me to enjoy it says something I think, and it is that juxtaposition I feel between that seriousness of performance or intent, and then just the montage of someone peeking their head through the door, asking another character what’s wrong, and we cut to this just outrageously visceral kind of body horror moment. And I think that works, that ‘over-the-topness’ with the kind of straight delivery often. Tell me about what kind of R+D went into the effects here for Body Melt. Was Maria Kozic the hair and make-up person?

PB: Maria is a well-known Australian contemporary artist, and I got Maria out of desperation, because I had that same problem where we met a few potential art directors and production designers for the film. The whole film was like, “No this isn’t broad-stroked farce; this is like the suburbs.” And “No, it’s not the suburbs as viewed by a Melbourne University graduate who’s never been to the bloody suburbs: this is what it actually is like if you come from those areas.” When you’re going to visualize it, it’s not going to look cinematic. It’s not going to look beautiful; it’s not going to look great. When you have a still from it printed, it’s going to look iffy. It pains me that cinema is so desperately ‘visual’ all the time, like it’s trying to be aesthetic even when it’s showing something grungy – it still has to muck around with the lenses and the grading to make it look as if it’s a deliberate art photo. I’m allergic to all that stuff, and so is Maria. Fortunately she agreed to be the production designer on it. And at the end of the movie, the credits have, like how you usually have BSC and ACE and all these acronyms after the names, well the one after Maria’s is SFA.

JDR: Which is what I think it is?

PB: It is what you think it is. And because Maria knew what my visual sense was, and she knew the culture that we were addressing there, it was very easy for her to understand that and just go ahead and do what needed to be done. Though there was still levels of stress she had to deal with, because you’ve got a huge crew.

JDR: I see Body Melt spoken about as this low budget film, and I’m watching it and thinking “this isn’t low budget”. It’s not a huge budget but it’s not low budget.

PB: It was $1.3 million!

JDR: Back in 1993, that was a fair amount of money.

PB: People say ‘low budget’ whenever someone wants to put down what they’re critiquing in movies, they always infer that somehow it’s cheap.

JDR: Ah, is that what you think has accrued around this film, this notion of it being ‘low budget’ that therefore maybe excuses or explains its crudity or vulgarity or something?

PB: It’s fair enough if you don’t like the movie – fine. The thing for me, Jason, is it’s impossible to offend me by saying something bad about something like Body Melt. You can say what you want – I don’t care (guffaw laughing).

JDR: What have you noticed that people think about this film over the years since it’s been released, which is 30 years ago now? Have their reactions remained the same? Has each generation reacted to this film as a critique, or as just a good time in the same way? Have you noticed change?

PB: I haven’t noticed a major change. It’s like anything that, dare I say, has some distinction to it - even if it be to its own detriment, in the case of Body Melt, because it certainly hasn’t helped me professionally since (laughter) – if there’s some distinction in any form of a cultural artefact, you either get it or you don’t get it. And I really like things that kind of say to you in the audience “you either get me or you don’t get me”. If you don’t get me: fine. There’s plenty of other stuff you can see. So that idea of being separate from the flow and the discourse, I’m very comfortable with that. It’s not to do with being an outsider, or rebellious, or contrary or anything like that. It’s just that there’s a billion ways to express a certain sensibility about a single subject. And everyone can come at it from all different angles, and I’m there to listen to the angle that’s got some deeper distinction to it. And so I think that what people are getting into in the movie and have been for the last 30 years – because frankly I don’t think there are many other movies made that same year in Australia that keep haunting their director as this one does with me – is that it didn’t fit in at the time. We couldn’t get an Australian distributor for the movie. It sold everywhere around the world. And when I say everywhere, I mean there’s even a Portuguese version of it that completely in its dubbing rewrite the story to make out that the doctor worked for the Nazis!

JDR: Wow!

PB: It was on laser disc in the States. It was everywhere – in Greece, Turkey, Russia, India. In India they edited 23 minutes out of it! (Laughs) That made it about an hour movie!

JDR: But hold on – did it not get a cinema release in Australia?

PB: It got a very limited cinema release - by us. We literally took it to the cinemas to show it, like the Valhalla cinemas and a few places like that. Very limited run, and the response wasn’t that kind of great, because at that time the idea of more of a ‘quality’ sense of Australian cinema – some kind of respectable form of Australian cinema, some form of cinema that had some decent social commentary to it – Body Melt is utterly lacking in all those areas. So fair enough it doesn’t fit there, but we were very surprised and a little upset that not a single distributor wanted to just take this on, even as a late night thing.

JDR: As you said earlier, it’s certainly haunted you, but if you do Google Body Melt, it just comes up – it’s quite clear that it’s become such a – well, ‘cult film’ is easy shorthand way of describing it, but it’s one that appears on lists. It appears in reference to our national cinema here, as an important film of reference. Philip Brophy, it’s been a pleasure to have you on the Screen Show: thank-you.

PB: It’s been fantastic being here, Jason.

Body Melt: Acting Degree Zero

published in Real Time No.2, Sydney, 1994Interview by John O’Neil

Philip Brophy cast his first feature film, the schlock horror movie Body Melt, from television advertisements. “If I see most actors in an Australian movie I groan; I think ‘Oh, God’,” he says. “What I’m groaning at is what most people see as a sign of quality; some sort of ABC-drama aesthetic. I’d rather some Martians just came down and blew them all away.”

And, in a sense, that is what happens in Body Melt. Brophy’s film is centred on a cul-de-sac in an archetypal Australian suburb, Pebbles Court, where the residents have swallowed both the promotional hype and pills of a drug company that promises “cognition enhancement,” not at all unlike Prozac. The only problem is a willfully mis-held missing ingredient. As a result, the pills lead to horrific mutation and essentially turn people inside out. A jilted, similarly mutated genius who lives in the country town of “Nowhere” is ultimately revealed to be responsible.

The art of performance was, for Brophy, at its highest point in a scene where a young married couple, played by Brett Climo and Lisa McCune (a Coles New World girl from television advertisements and now a star in Blue Heelers), are confronted with the consequences of the drug. McCune’s character, eight months pregnant, discovers her unborn child is feeding off her. The genesis of the sequence was a television commercial for health insurance starring another, since successful theatre and film actor, Zoe Carides. “She did this amazing ad that is just so disgusting,” says Brophy. “She’s down because she’s just had a baby in hospital. It’s all white. It’s just got this sterility to it. She’s handed her baby which she sees for the first time and then she’s unsure what to do. They’ve got this music with a woman who sounds like she’s orgasming while she sings piano breathlessly and there’s a tinkling piano. It’s a soft-rock ballad and then, suddenly, the baby smiles and Zoe breaks into tears and touches the little baby’s forehead with her forefinger. I thought: ‘Great, this is the person to drop her placenta.’”

Carides was unavailable but McCune (Cheryl in the film) was an equally “nice” stand-in whose performance enhanced the original. “Doctor,” she asks on the phone. “Is it possible to drop your placenta one month prior to birth?” Her unborn child then appears to rape her before the placenta suffocates her husband.

Brophy’s previous film was the 47-minute Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat which is now available on video. Ironic and funny, it is driven by a synthesised musical soundtrack and Brophy’s actors, principally Jean Kitson and Phillip Dean, utter just 11 lines. They include: “Well, God, piss on me,” and “Knock your scrote on that dick-twister.”

“It’s virtually a form of puppetry,” says Brophy of film acting generally, and of Salt, Saliva… in particular. “It’s not that far from pornography: ‘Okay, pan back, right. Okay jerk off a bit to get an erection. You up yet? You up? Ok, quick, go in now. You scream. You scream. You scream.’ It’s not far removed from a dramatic situation where a director’s told the actor: ‘Ok, you come back to this mark. You stand there. You say that line, then turn. We’ll do the focus-pull on the lenses at that point, we’ll shift the reflector boards around and you move across there as the track comes back.’ Whether they’re saying: ‘I think we should get a divorce’ or having their head dunked into a bowl of shit (as occurs in Salt, Saliva…), the content of that action becomes slightly nullified or overridden by the mechanics of the whole situation.”

Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat is a series of days in the life of “The Man” played by Phillip Dean. “Phillip always struck me as being like one of the Thunderbirds. I don’t like actors who are in my face, the whole Method approach. This emotional outpouring; this angst-ridden identification with the onscreen person etc,” Brophy says. As a result, Dean’s most contemplative and demanding performance moments occur while shitting — which Brophy acknowledges a great character actor like Robert de Niro could do well. But naturalism is a style to which Brophy doesn’t aspire.

“That’s only one option of how you can actually look at these strange, granular, floating, abstract, pseudo-photographic, ghostly images of people on a screen,” he says of realism. “In essence they are highly iconic and hieroglyphic anyway, just by their photographic status, despite their fleshy appearance.”

The consequence is that for Body Melt he has cast soap stars and other actors for their preconfigured iconography, and the icon that looms largest is Gerard Kennedy of Division Four and Homicide fame. “It goes back to this artificial logic of the whole film,” Brophy says. “Why have a cop in a film who is really only a plot device and try to pretend that somehow the person’s a character. Why not just go straight to an iconic instance of copness?”

Brophy also casts on the basis of voice. “The bulk of all changes in anyone’s expression doesn’t particularly come from their face,” he says. “I think the face is just a slight adjunct to the much greater range of tonal differences that happen in projection: shifts in pitch, paraphrasing, beats and what not. The projection, quality and delivery of the voice gives a much more precise impression of what the character is. The face doesn’t move around as much. This is marked when you’re watching something on a screen where the face just hovers there in a sense and is very often quite internalised in its projection.”

Body Melt was shown at the Melbourne Film Festival in June 1994 where, according to Brophy, it achieved the highest attendance of any film show. It has been sold to distributors in New York, England, Canada, Mexico, Turkey, Cyprus, Malaysia, the Phillipines and Thailand, and negotiations continue with Europe and Japan. In Australia, Brophy and producer Rod Bishop are organising theatrical release themselves.

Snot Funny - It's Body Melt!

published in Fangoria No.131, New York, 1994Interview by Michael Helms

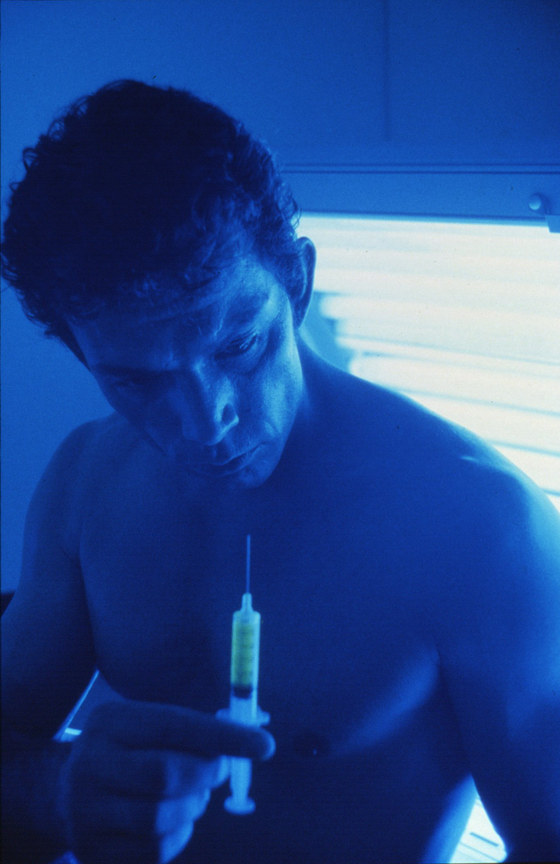

Out in the vastness of the suburbs surrounding the city of Melbourne, Australia, people are knocking themselves out just to stay in shape. And it's getting messy. Around 50 slime-soaked makeup FX shots will depict the results in Body Melt, the first Australian film specifically designed around special makeup FX scenes.

With the exception of some mid'80s work from now LA-based producer Tom Broadbridge (Out of the Body, Stones of Death) and the generic in-house -horror product (Blood Moon, Dead Sleep) that routinely pops out of the Queensland studios where Stuart Gordon made Fortress, Body Melt is almost a complete anomaly. being the first Australian all-out shocker to go before the cameras in ages. It's taken nearly half a dozen years for the people behind Body Melt to finally run the gauntlet of official Australian film funding bodies, convince them collectively of its potential worth and be ready to proceed with enthusiasm when the project was eventually green lighted.

Now on location at last, Philip Brophy, the somewhat relieved co writer, director and soundtrack composer of Body Melt, ruminates over a breakfast table on the torturous path that is just about the only option for feature filmmakers without private backing Down Under. "Here we have a variety of organizations that are not unlike America's National Endowment for the Arts and the American Film Institute," he says. "The Australian Film Commission is like a mix between the two, and is an attempt to fuse industry with culture. The kind of films this body wants to make, though, are respectable, sensitive, socially aware, politically correct and uniquely Australian. This, in most cases, means they support totally boring movies. The will to go on sank really low at times, but fortunately we were able to get the steam up and start haranguing them all over again. Somehow I convinced them that what they need is a film like Body Melt."

And what sort of film is it, you may ask? Besides being a totally low-budget exercise (around $2 million Australian), Body Melt, as its title suggests with great subtlety, is a horror flick highly concerned with the possibilities of distorting the human form. "Basically, every major horror event in the film centers on a part of the human body and something phantasmagorical is happening to it," Brophy explains. "It was written in a free-form association way of' looking at beautiful ads on TV and just wishing that the world that most of those ads depicts would explode and cave in. In a nutshell, it's The Brady Bunch in hell, the suburbs on weird drugs and the apocalypse next door."

Before consuming one last piece of toast and getting on with the day's work, Brophy adds, "Generally, everyone has become much more obsessed with the living body. That's what's so great about modern horror movies of the last decade or so. Whilst many present spectacular explosions of death, what they' re really about is what the body actually does when it's living. It might, die afterwards, but it's about how a body moves, pulls itself together and turns itself inside-out. They're the kinds of ideas I'm thinking of with Body Melt, picturing suppositions like, 'What would happen if someone's Adam's apple split open and ii stretched apart so their vocal chords came out and strangled them?' "

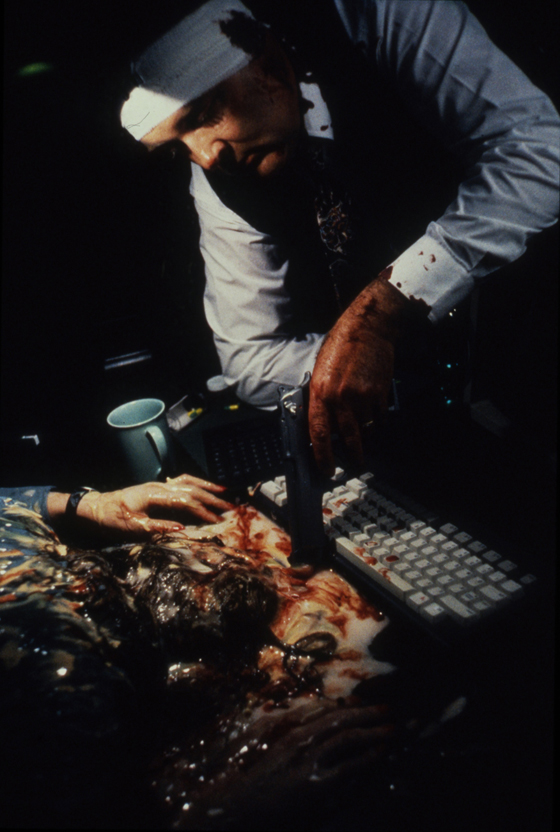

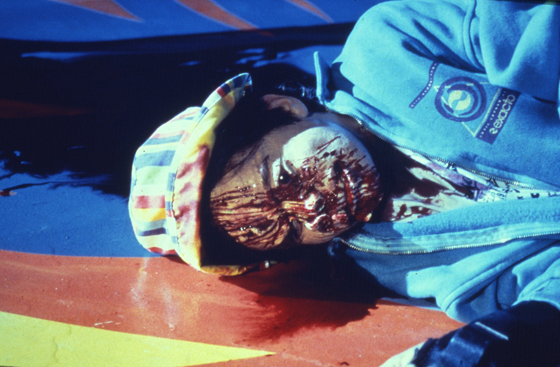

Minutes later, we re standing inside a university morgue that is just one of the several real-world settings utilized by the Body Melt team. While shooting entirely on location creates as many logistic problems as it lessens economic ones, the only real trouble this morning is entailed in getting to eyeball the amazing $26,000 Skinflex corpse created by Bob (Dead ALive) McCarron. Necks are craned and all eyes are directed towards the slab in this overcrowded room, upon which lies a naked, autopsied male body with the contents of its chest cavity and part of its stomach on display for all to see. This is the first victim of Body Melt; he has large, ugly, gill-like slits on his neck. In death he appears so realistic that many of the onlookers (except for your fearless reporter, of course) decline 1st assistant director Euan Keddie's gleeful invitation to cop a feel of the neatly placed but entirely synthetic intestines. Filming then proceeds smoothly as two sweeping close-ups are made of the corpse: one with a towel strategically covering the body and another not so encumbered for the uncut version. Italian filmmakers have been taken to court for less gruesome scenes than this.

"What I'm after, and what I' ve asked Bob McCarron to set out to achieve," says Brophy "is for the audience to really feel like it' s their own body on the screen. That's why, although we didn't really go for realism, we also didn't go for a totally over-the-top, theatrical, fake, highly stylized approach either. The bottom line was always the question of how someone in the audience was going to respond to an image of a body doing something. And that was the center, the focus of every transformation scene. Not how realistic it looks, or how gross it is, but how an audience member is going to feel while they' re watching it."

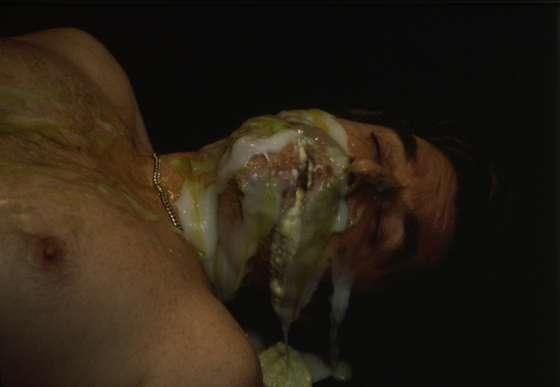

While Brophy hopes Body Melt is afforded the chance to reach the widest audience possible, Americanization of the project has not been a consideration. "I've watched a lot of American movies; now you can watch at least one Australian film," he laughs. Rephrasing that statement a tad more diplomatically, he states, "I hope that Americans can enjoy an Australian movie as much as I' ve enjoyed many American movies." On a wider but not unrelated note, Brophy also realizes that Body Melt is something of a test case in relation to his own future and the financing of other Australian genre projects. Before heading off to begin work on what is sure to be a unique horror soundtrack, Brophy relates an anecdote from what he otherwise describes as a controlled and efficient shoot. "We had one scene that required this actress to do this really vile thing with a huge tongue she had to vomit out," he recalls. "There were actually four different tongues that Bob had specially made. She had to do this scene with goop and slime and all sorts of shit all over her. When she performed it, she really looked like she was choking on the tongue."

"Now remember, we' re talking about an actress who, like nearly all her fellow cast members, is a straight performer and wouldn't even contemplate watching any sort of horror film in her spare time," he continues. "Yet here she was, doing something grotesque with ease, and very convincingly. Then we had to place some fake phlegm around her nose, and she caught sight of herself in a reflection on the glass that was shielding the camera from any splatter, and she just freaked. She could handle this giant tongue and all this other shit, but this little bit of snot completely unsettled her." Get set to be equally unnerved when Body Melt arrives in the U.S. sometime this year.

Text © John O’Neil & Michael Helms. Images © Philip Brophy.