Background

Body Melt is a $1.65m feature film shot on Super 16 with a 35mm blow-up and Dolby Surround audio. Funded by the Australian Film Commission and Film Victoria, the film was shot late 1992, with post-production completed by mid-1993.

The score for Body Melt comprises 9 themes. Each is attached to one of the many characters in the film, and takes the shape of a completed 'song' rather than an impressionistic or atmospheric piece of music.

Credits

Score: composed, performed & produced by Philip Brophy

Sound design: Craig Carter & Philip Brophy

Original 35mm Dolby Surround mix: Steve Burgess

Dolby Digital 5.1 reconstruction: Philip Brophy

Overview

Transcript from the Blu-Ray commentary

Music Score

One thing I’ve always done when providing music for a visual medium is work out a conceptual logic for what the music should be doing, and why it should be doing it. To say that music should be providing ‘emotional support’ for a scene is part of what I call the ‘pacifier’ approach to the soundtrack. This is where the music, sound and mix is normalized to effectively hold an audience’s hands through their ear canals. The conservative soundtrack subliminally lets them know that everything is okay. A very moralistic approach arises here, where film scoring thinks it’s important to let the audience know when they should be sad, when they should be happy, when they feel like there should be some adrenalin moving through their system. I’ve always thought that emotionally, morally and ethically, an audience should work out any of that shit for themselves. If something ‘bad’ is happening in the movie, they shouldn’t be spoon-fed some emotive music that suggests that they should be wringing their hands in grief over the awful things that are being depicted on a screen.

With Body Melt, I certainly didn’t want the music to convey any emotional state – mostly because the film is largely full of ciphers and stereotypes. Sure there’s ‘real people’ there, but they’re being brought to life by some fantastic actors that are completely in synch with the idea that these are quite theatrical figures and tropes that they’re performing. I’m sure that no-one would be thinking Body Melt is a serious quality drama, but I was serious about working with the actors to achieve a type of performance that wasn’t humanist, that allowed them to completely inhabit the characters without at all suggesting that there was anything further ‘real’ about their characterizations. This was important from a directorial point of view, because it then suggested the logic I would take with the music – one that would not emote anything, but would be in keeping with character types of the film and its parodying of outer-suburban life.

So, I composed a musical ‘type’ rather than a musical ‘theme’ for each of the characters. For example the music that accompanies the newly-wed couple of Cheryl and Brian Rand expecting a baby is lite sophisticated muzak: the kind of thing that would be playing on BBC or ABC, something evocative with a slight jazz feel, not too taxing, doesn’t require a specialist ear, but something sophisticated all the same. The instrumentation is acoustic guitar, some light break-beat in the background; a little squidge of didgeridoo (everything on the ABC TV here has a didgeridoo playing somewhere, usually with reverb and from a sample library); and some reprehensible muted trumpet, mimicking Miles Muzak Davis. There’s something to offend everyone in that particular track. So I was thinking of the characters’ lifestyle values and sensibilities, and then making music for ‘their world’. The music doesn’t have any aural winking to the audience – no nudging to let you know it’s a parody of that kind of music.

In the case of Paul Mathews – a ‘music industry man’ working at a lite FM radio station – I’ve got a somewhat perverted ‘Adult Oriented Rock’ track. It’s got some thudding bass; it’s slightly funky, but again, it’s staying in a very tasteful area. There’s some electric guitar plus some sampled tolling bells – I was think of them tolling for his death, cos he will certainly die a spectacular death. For the ‘mutant family’ there's a bastard version of Prog Rock, with a range of edited guitar samples, and even a Funkadelic guitar solo line chopped up and cut through it, and some Nu-Metal Proggish snare thwack. For the two Italian boys, there’s a slightly perverted Italo House track of the late-80s thumping type: some Black Box-style vocal samples, grand piano tinkling and deep organ. For the Noble family when they reach their dream holiday at Vimuville, there’s a more standard approach to Muzak. It's actually a 4/4 lite beat edited from Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five”: the ultimate Easy Listening, further neutralized by placing the 5/4 into 4/4. Lots of analogue string pads give a queasy lush feeling to the track. There’s then a couple of Techno-derived tracks, to match the drive of the Vimuville corporation. There’s one theme to go with Dr. Carrera's drive to create the super-human body; there’s another one to go with Shaan, the bitch who wants to market the hell out of these new drugs. All the Techno components on these tracks are all constructed in the ASR from samples performed on analogue synths – mostly a Korg 2000 and a Roland SH1. It was important to acknowledge the Techno legacy that’s caught up in the 90s pharmaceutical ethos, but it was equally important to give the tracks that analogue tinge. Back in the 90s, analogue sounds sounded wonderfully plastic and inappropriate. They sounded cheap, mass-produced, and the kind of thing that would sit next to detergent in a supermarket.

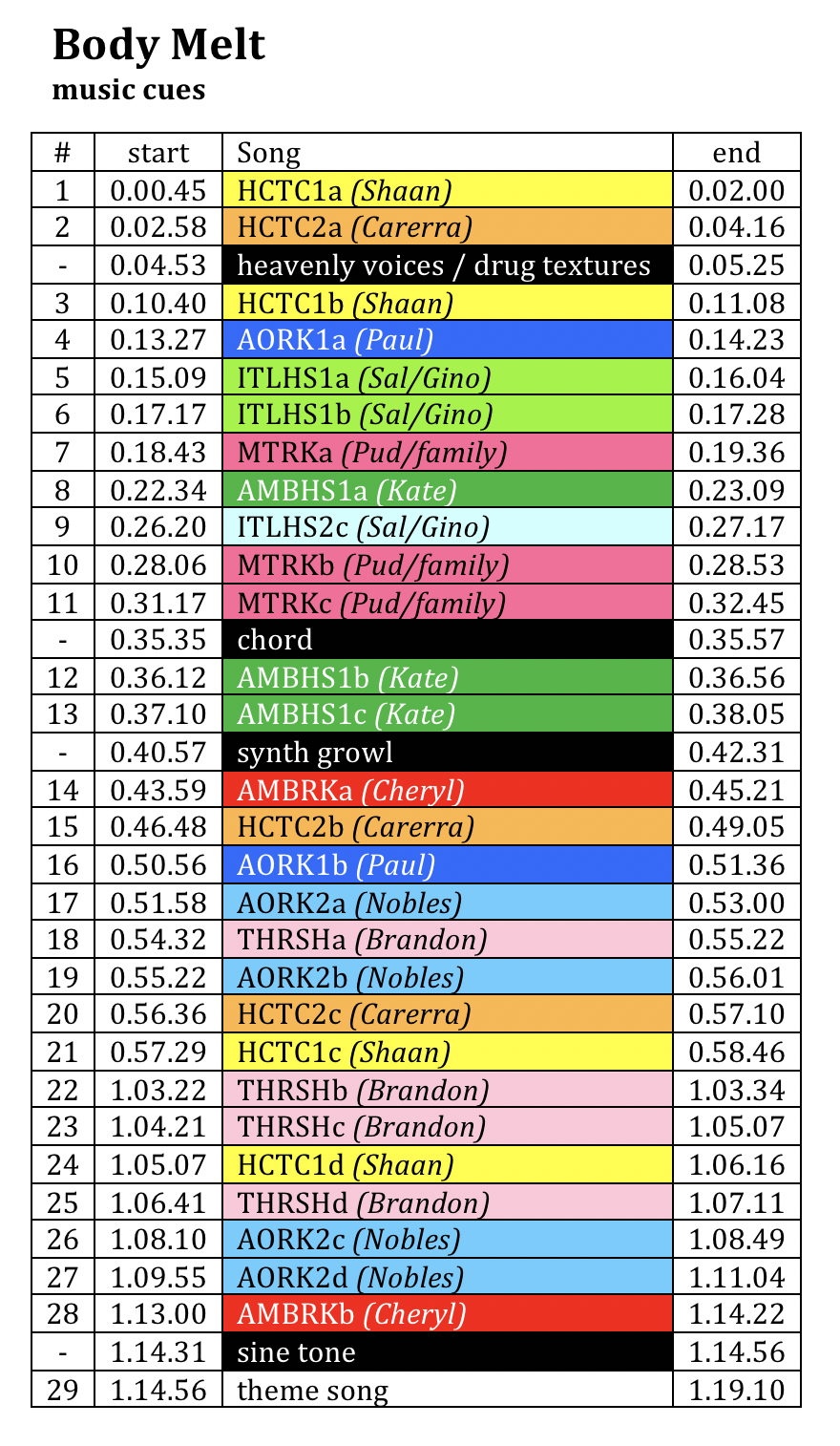

I made complete tracks – not cues. What would be the music for these characters? I made stand-alone tracks, and then I would break it down as if it was a track I had sourced from some other album, and then cut them up to use as cues for the film. It was maybe a long-winded process. I spent a lot of time making these tracks which then were gutted, but as the composer for the film I didn’t feel I could just do cues. I needed to have a clearer framework that would allow me to be more objective about my approach to the music. This deconstruction of the stand-alone tracks usually involved removing different elements of the track. It’s an approach I learnt from listening to John Carpenter’s scores, whereby he would compose a theme but present a reduction of the theme for the various cues in the film. I always thought that was a great way to get into the drama of a scene – by exposing the musical skeleton.

Sound Design

I was largely responsible for providing all the phantasmagorical sound effects, which I delivered to Craig Carter who also performed sound design and was the sound editor working on the film. When I was doing both the music and the sound effects, I didn’t work with any time-code, no computer screen system. I would simply watch the sections telecined on a VHS tape and then get the rhythm, tone and weight of the scenes, and then without any image would construct the sound effects. Then I would edit them up in the ASR workstation with layers of MIDI-data modulation, and use LFOs and envelopes to move the data through the stereo and rear space. At that stage I was working with 3 channels (front-left, front-right and rear mono). Then I would play the video and have my finger paused on the internal sequencer of the ASR and hit it at the right moment to check how it was all fitting together. This is the general way in which I’ve worked with film when I’m doing sound and music: I watch the screen as little as possible. I don’t want to be affected by any image information; I want to work with the sound in its own right and to have it generate its own presence, identity, and character. And to do so with me thinking in a primarily sonic way. Then I can check what happens when I feed it with the image.

I’m very happy with the special sound effects I cobbled together with the sampler for Body Melt. These sounds were all recorded by myself and they’re all extreme close-up sounds of different textures: low rumbles – lots of different kinds from wooden to metallic – rolling balls along the wooden floor of the studio I had at the time; all different mic perspectives of our cappuccino machine; refrigerator compressor engines; lots of different types of food frying or boiling. It was a very elemental approach to the sound effects. I’d record them, digitize them into the ASR, and then do quite complex waveform editing, constructing loops, invoking modulation to pick up different loop edit points and based on have selected LFO waveforms cause shifts in the stereo space. I was exploring ways in which to have the sounds organically bubble and crackle and come to life – in both frequency and spatial ranges. Craig also provided larger scale sounds like wind and ocean waves he had recorded, which I then put into the ASR and performed similar transformations. As is the case with these type of fantasy and horror sound effects, things are very layered: wind, combined with cappuccino froth, combined with slamming weights into a bean bag, combined with the tail end of a wave break, combined with spittle put onto a mic. You put them all together, and it kind of overloads the brain a bit when you a hear a sound like that. It sounds intensely real and completely unreal at the same time. One thing’s for sure: it sounds quite visceral, and it sounds like it is appearing or manifesting itself right before your ears. It doesn’t sound like a sound-bite or clip.

Technical

Transcript from the Blu-Ray commentary

Reconstruction in Dolby Digital 5.1

It wasn’t until I embarked on restoring the sound for the 2k restoration and Blu-Ray release of Body Melt that I want back and played the DVD – released in 2002. In fact, I’d never even played the DVD. So it was a shock to find out that despite all the DVDs around the world of the film claiming to be in Dolby Surround, the DVD actually contains the safe broadcast mix – what they call a television mix. It’s not even in Dolby Surround, which was the soundtrack format for the original 35mm print released in 1993. Dolby Surround (the format at the time) has 4 discrete channels of audio: one mixed into the centre speaker, a stereo spread placed in the front left and right speakers, and a mono channel playing in the rear array of speakers. (Plus the encoding with Dolby Pro Logic Surround at that stage involved a frequency roll-off at the top for the back speaker playback.) The television mix on the DVDs has no multi-channel breakdown: it’s essentially stereo, with a phantom centre and no surround content.

So when it came to making the 5.1 mix of the film, my original concept was to go back to the DVD mix, and simply extract the audio from the multiple discrete channels on the DVD, pitch-correct them from 25 frames per second (the rate for video playback) to 24 frames a second (the rate for film projection and Blu-Ray restoration) and join it to the restored digitized footage. I could then embellish components so that there would be full-frequency range in the rear, as well as a full stereo spread there too. I then embarked on a search for the LTRT – the left-track/right-track mix that is mixed to 35mm magnetic tape. This is the mixdown of 4 tracks of information that are matrixed onto 2 tracks of the mag tape. These dual tracks are then sent off to be used for the making of the 35mm neg soundtrack – those two squiggly lines that appear on the side of the sprocketed film strip. It’s what they call the ‘stereo variable area’: two lines matrixed through the Dolby process to carry 4 channels: the centre, the front-left, the front-right, and the rear.

The 35mm mag tapes were sent up to the National Film & Sound Archives in Canberra. They digitized it running at 24 frames a second. I then received those compacted files, then had them separated so that I had 4 tracks of information. The most important track I was after was the centre speaker, which contains the dialogue without any other music or atmospheres bleeding in. But unfortunately when I finally analyzed the breakdown of the files from the LTRT, I found out that there was a lot of spill going into the centre speaker, mostly of the front-stereo atmospheres. And even some of the music bled here to. So I was able to do some separation, but I still had to deal with not being able to extract completely discrete information from the matrixed 4-track. This is because – I’m fairly certain – the mix that was done at Soundfirm in Melbourne back in 1992 erred on the side of caution, and didn’t choose to do radical separation. Of course, this was to ensure that most cinemas would have an achievable threshold to reach for containing the music and sound effects with the dialogue. For most film mixing, it is important to make sure that the dialogue is there right in front and above everything else.

What I then did was track down the M+E – the Music and Effects track. In the early 90s the main way this was produced was on SP-Betacam tapes – high-end then, but now superseded by all forms of digital encoding. But the Betacam tape runs at 25 frames, mostly to be supplied to international sales agents for selling the film onto other countries for video, television and cable release. (Buyers of the film then have the option to use the M+E tracks and then record their own dialogue track in their own language.) It was fairly straightforward to re-conform the running speed to 24 frames per second. This was the frame rate at which I produced the music and the special sound effects (all the bodies blowing up, etc.) in my studio prior to it going into the multi-tracks at Soundfirm. However, even the M+E had problems with separation. I still wasn’t able to fully separate bits of music carrying over into tracks I thought were discrete. So after numerous experiments, I managed to work out a way in which I could keep the centre track from the LTRT, use the stereo LTRT tracks as a light ambience, and use the main effects track from the M+E. These were all lined up to produce a mix between the front-left, front-right and centre speakers. This approximated fairly closely the original 35mm Dolby Surround mix.

The thing that saved me, though, was that the bulk of the special sound effects were all done on an Ensoniq ASR-10 sampling workstation. The music was also done on this workstation. I was able to retrieve all the original files (on ZIP and 3.5" floppy discs!) and re-edit them within the workstation to reconstruct the sounds in a full quadraphonic mix. These quadraphonic passes of all the music tracks and cues, and all the special sound effects were digitized and blended in with the multi-track containing the LTRT passes. That’s what is heard in the 5.1 mix. It’s an attempt to recreate the optimum cinema viewing experience sound-wise that was in the original film when it was theatrically projected on 35mm in the early 90s. The only difference really is in opening up the rear spectrum and spatial domain.

Further to that, I did a slightly ‘harder’ mix: I made it more dynamic and punchy, so that the dialogue is sitting in there, but rather then have all the other sound behave politely I’ve gone down the other path and made them behave a bit more rudely and have a more guttural, physical presence. I think that while that might be warranted for chamber dramas of middle-class people having dinner conversations and worrying about their relationships, in a film that’s about experimental drugs that are being delivered to unsuspecting residents in an outer-suburban cul-de-sac that cause their bodies to melt and explode and do strange things, then I think the guttural sound effects should have more of a physical presence. That was the intention in the original mix. It’s been great to revisit that and put it all together.